The Skyscraper Museum has presented two series of webinars designed as an online course on the early development of the skyscraper – the one below, Rewriting Skyscraper History in fall 2020 and a second Work in Progress in spring 2022.

Rewriting Skyscraper History: Looking Back from the 21st Century

William Baker, the structural engineer of the Burj Khalifa, the world’s tallest building, observed in 2007: "If skyscraper construction had stopped in 1975, one would say that the tallest skyscrapers are made of steel; in the United States; and are office buildings. Today, one would say they are composite or all concrete; in Asia or the Middle East; and likely to be residential."

That formulation may have changed a bit in recent years with the rise of Chinese supertalls, which are most often mixed-use, but the succinct summary of both 21st-century towers and a 20th-century definition of “skyscraper” is spot on. Indeed, skyscraper history has too long suffered from a fixation on steel skeletons and glass curtain walls. Click on “skyscrapers” in the SAH Archipedia and the definition, via Getty Art and Architecture Thesaurus (AAT), is: “Exceptionally tall buildings of skeletal frame construction.”

From the perspective of the 21st century, though – as our new exhibition SUPERTALL 2020 illustrates – concrete has become the nearly universal material of the world’s tallest towers.

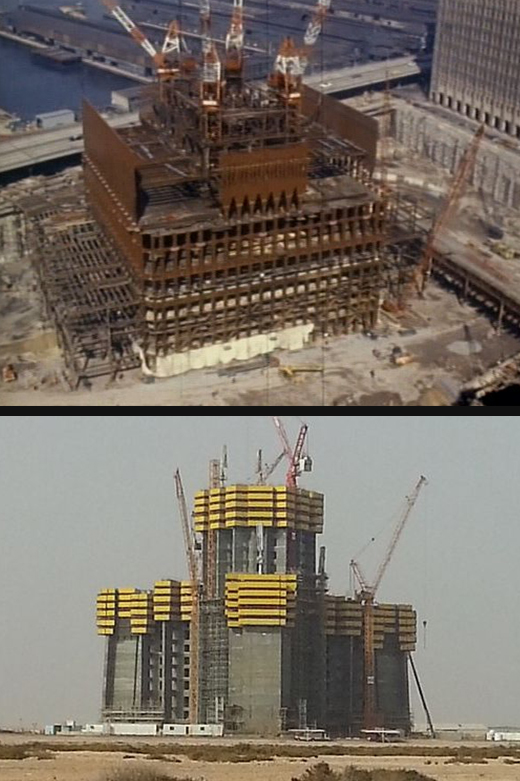

Concrete is employed in a range of structural systems, but a heavy concrete core is the standard feature of all supertalls. And the engineer of the next world’s tallest building (if completed!) Jeddah Tower, calls its structure a “pure bearing wall.” Clearly, we need a more inclusive definition and history of the skyscraper more appropriate to the 21st century. That is what this fall symposium will attempt.

The evolving symposium will engage an established group of scholars – all of whom have all specialized in some aspect of skyscraper history and have collaborated on some of the Museum’s earlier programs – to consider broad questions about the early history of the type without falling into persistent 20th-century narratives, including an emphasis on “firsts;” rivalries over stylistic expression; or competition for superlative height and lists of tallest buildings. Instead, we will consider the lags and learning curves often inherent in the adoption of new technologies into established systems of supply, construction, codes, and other factors.

SCHEDULE

Click on the WEEK schedule below to watch videos of past lectures:- INTRO: REWRITING SKYSCRAPER HISTORY

- WEEK 1: New York & Chicago, from the 1870s: ELEVATORS (Passenger) & ELEVATORS (Grain)

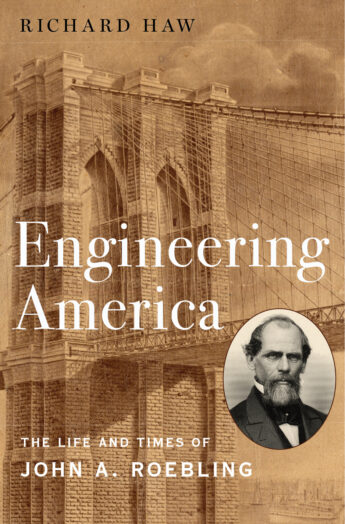

- RELATED: ENGINEERING AMERICA: John Roebling's Brooklyn Bridge

- WEEK 2: Masonry to Steel, 1870s-1890s: How and When Masonry Transitioned to Steel

- WEEK 3: BUSINESS BUILDINGS: Corporate vs. Commercial Skyscrapers

- WEEK 4: THE TALL (NOT)OFFICE BUILDING: Other Uses, Other Issues

- WEEK 5: Tall Buildings, Labor, and Capital

- WEEK 6: Alternate Histories of the American Skyscraper

- WEEK 7: Better Questions? Better Definition?

Santa Fe Elevator, Damen and the Chicago River. Courtesy of Thomas Leslie.

New York & Chicago, from the 1870s:

ELEVATORS (Passenger) & ELEVATORS (Grain)

Introduction to Rewriting Skyscraper History

By Carol Willis (bio)

Chicago’s Other Skyscrapers: Grain Elevators and the City, 1838-1957

By Thomas Leslie (bio) Monday, 9/14

Elevator Office Buildings, New York and Chicago from the 1870s

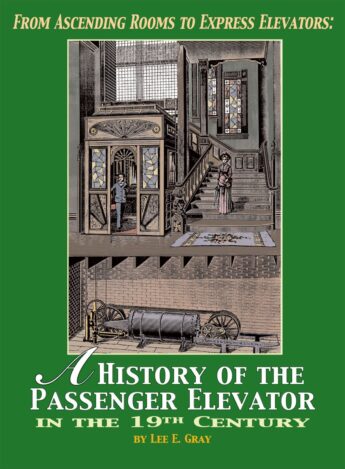

By Lee Gray (bio) Wednesday, 9/16

For Week 1, we present a pair of lectures by two historians, Thomas Leslie and Lee Gray, who will focus complementary talks on very different subjects that raise issues about how technological inventions and the embrace of new materials impact the form and functions of buildings. Two kinds of elevators – passenger and grain – provide the points of comparison.

In one case, the introduction of passenger elevators in office buildings in New York from 1870 – a delayed adoption, after more than a decade of use in stores and hotels – is often identified as the origins of the “skyscraper.” Lee Gray, the preeminent scholar of elevator history and author of From Ascending Rooms to Express Elevators: A History of the Passenger Elevator in the 19th Century (2002), will discuss the “dialogue of invention and need” that characterized the earliest examples of the design of elevator office buildings in both cities.

In Chicago, while tall office buildings were slower to appear and shorter than contemporaries in New York, there were other impressive structures that dominated the skyline: grain elevators. Because none of these grain elevators survive, their history has been mostly forgotten. Thomas Leslie, author of Chicago Skyscrapers, 1871-1934 (2013) thoroughly explored the typology and technology of grain elevators in a recent Journal of Urban History article “Chicago’s Other Skyscrapers: Grain Elevators and the City, 1838-1957,” which he will summarize in his talk.

The two lectures, each about 40 minutes, will be held on different nights, and will include dialogue and Q&A with the two speakers, as well as with Museum Director Carol Willis.

Readings

One of the 19th century’s most brilliant engineers, inventors, and successful manufacturers, John Roebling immigrated to the US from Germany in 1831. He became wealthy and acclaimed for bridge design and construction, and by 1867 had begun work on his masterpiece, the Brooklyn Bridge. Richard Haw, author of Engineering America: The Life and Times of John A. Roebling (May 2020), as well as two earlier books on the visual and cultural history of the bridge across time, will place this transcendent marriage of masonry and steel cable into the context of Roebling’s life’s work.

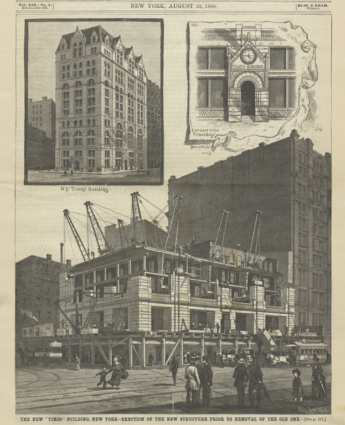

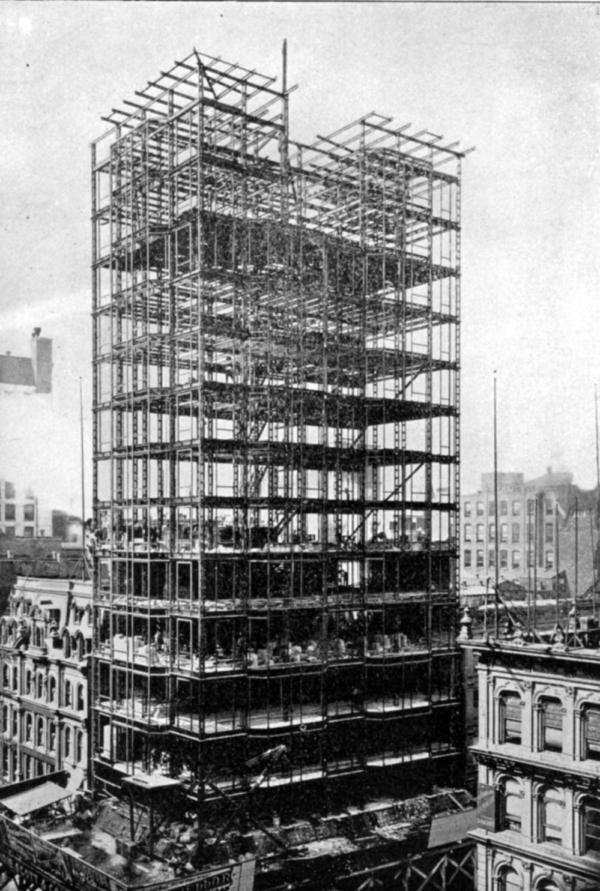

"The New 'Times' Building, New York-Erection of the New Structure Prior to the Removal of Old One." Scientific American, August 25, 1888, cover

Reliance Building, Chicago.

Masonry to Steel, 1870s-1890s:

How Masonry Construction Transitioned to Steel

Masonry to Steel: Technology Changes

By Donald Friedman (bio) Tuesday, 9/29

Brick, Iron, and Steel:

Material Matters in Chicago Skyscrapers, 1870–1890

By Thomas Leslie (bio) Wednesday, 9/30

For Week 2, we present a pair of programs led by New York structural engineer Donald Friedman, author of The Structure of Skyscrapers in America, 1871–1900, and historian of Chicago Thomas Leslie, which revisit the fabled architectural rivalries of America’s largest and most innovative cities. Their talks will keep a tight focus on the key decades of the 1870s, the beginning of the end of “the age of masonry,” and the dawn of mass-production of rolled steel I-beams, which from the mid-1880s offered new economies for construction. Yet the eventual marriage of masonry and metal took time to birth the full steel skeleton, often called “the Chicago frame.”

Leslie and Friedman will explore the ways that traditional bearing walls enlarged window openings to illuminate interior workspaces until the wall became, in effect, a frame, and how hybrid systems of “cage construction” served practical purposes and were slow to disappear in practice. Both emphasize how construction moved toward industrial materials to reduce the cost of skilled labor, especially bricklayers. In Friedman’s succinct formulation: modern structure is industrialized structure.

These programs will build on several past lectures at The Skyscraper Museum by both speakers: the videos of these previous talks are highly recommended as background for this discussion.

Donald Friedman, Structural Systems of Early Skyscrapers.

The American Surety Building, 100 Broadway, completed 1895. Collection of the Skyscraper Museum.

Park Row Building, completed 1899, Library of Congress.

BUSINESS BUILDINGS:

Corporate vs. Commercial Skyscrapers

Business Buildings: Landmark Skyscrapers in New York

By Gail Fenske (bio) Monday, 10/12

Tall and Tethered: Telephone Buildings in the City

By Kathryn Holliday (bio) Wednesday, 10/14

For Week 3, three scholars of the skyscraper, Gail Fenske, Kathryn Holliday, and Carol Willis will address an opposition that has long characterized the framework for understanding the history of tall buildings – corporate vs. commercial – and ask: “What do those words mean, and how do they apply to skyscraper history?”

This week focuses on use, which architects generally call “program.” Office, residential, manufacturing, and commercial (meaning rental) are the terms that generally describe the different uses of high-rise buildings. Yet, one can argue that the most basic commonality in the vast majority of skyscrapers is that they are buildings erected to produce space for rent: i.e., all these uses are urban commercial architecture.

The idea of “corporate architecture” as applied to skyscrapers needs new scrutiny, especially in the early age of the rise of the corporation in the U.S. and especially in New York City in the last decades of the 19th century. Certainly, corporate headquarters, “branding,” and competition played a role in the inspiration and investment in early skyscrapers, as Holliday and Fenske will illustrate. But, as Willis will argue, most “corporate” buildings included a significant portion of rental space, and from the 1890s, speculative real estate drove both the height and volume of high-rise construction. Discussion will ensue!

This discussion builds on several past lectures at The Skyscraper Museum by each speaker: the videos of these previous talks are highly recommended as background.

Kathryn Holliday, Vertical Expansion: Telephone Infrastructure and Density in the Urban Market

Kathryn Holliday, A Tower To “Wake Up the Nation:” the New York Times in Times Square

Gail Fenske, The Woolworth Building: Highest in the World (2013)

THE TALL (NOT) OFFICE BUILDING:

Other Uses, Other Issues

THE TALL (NOT)OFFICE BUILDING: Hotels

A.K. Sandoval-Strausz (bio) Wednesday, 10/28

THE TALL (NOT)OFFICE BUILDING: Skyscraper Lofts

By Andrew Dolkart (bio) Wednesday, 10/28

Week 4 pointedly enlarges our focus on urban commercial architecture to examine two lesser-studied types of tall buildings by use: hotels and lofts. Urban historians, A.K, Sandoval-Strausz and Andrew Dolkart, will draw on their detailed studies and analysis of these distinctive development types – Sandoval-Strausz in his book Hotel: An American History, and Dolkart especially for his study of skyscraper lofts in New York’s Garment District. For each, the analysis of the design and function of the architecture is connected to the social and economic construction of the industries they accommodate, as well as their urban context.

This discussion builds on several past lectures at The Skyscraper Museum by each speaker: the videos of these previous talks are highly recommended as background.

Andrew S. Dolkart, Developing the Garment District

Tom Mellins, Hotels: Big and Tall; Carol Willis, Lofty Lofts in The Rise of the Skyscraper City

Readings

Tall Buildings, Labor, and Capital

Skyscraper Labor and the Places of Labor Protest

Joanna Merwood-Salisbury (bio) Tuesday, 11/10

What are the social and political dimensions of industrial innovation and technological change? In the 1880s and ‘90s, Joanna Merwood-Salisbury argues, the skyscraper was the subject of an ideological battle, as both the symbol of capitalism’s triumph and the target of anti-capitalist protest. As metal replaced masonry in tall-building construction, traditional building trades such as bricklayers and carpenters lost power and new trades, including ironworkers, gained importance. General contractors, architects, and engineers organized into professional groups to manage the complexity of industrialized construction.

The tall buildings they designed and erected were occupied by new kinds of urban workers – not only office employees but also immigrant laborers engaged in manufacturing. Tracing labor protests in the construction industry in Chicago in the 1880s and the movement to improve working conditions for garment-industry workers in New York’s commercial lofts in the early twentieth century, Merwood-Salisbury examines the formation of unions uniting trades-based groups with ethnic organizations, as well as the public spaces of their protest movements.

Readings

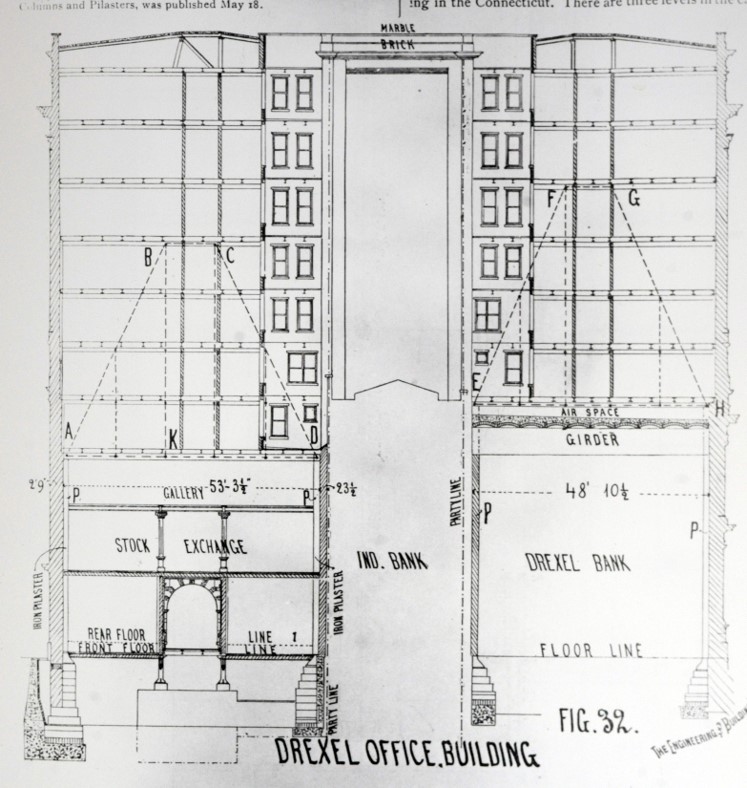

Is it possible that Philadelphia is the birthplace of the skyscraper? George Thomas, preeminent scholar of the work of that city’s 19th-century genius architect Frank Furness, argues that critical breakthroughs in modern construction systems came first, not from Chicago or New York, but from Philadelphia, where engineers and architects for the powerful Pennsylvania Railroad played a key role in translating their experience into high-rise office buildings. Thomas’s provocation will focus in particular on the work of Furness’s principal competitor, the Wilson Brothers, led by engineer/ architect Joseph Miller Wilson (1838-1902).

With unique professional training, including two years of studies of metallurgy in addition to engineering training at RPI, Wilson became the chief of the bridge department for the Pennsylvania Railroad in 1865, and in 1875 was assigned by the railroad to design the principal buildings for the 1876 Centennial Exhibition. In 1876, he formed the Wilson Brothers, bringing together an array of professionals who served clients across the western hemisphere. Their Broad Street Station in Philadelphia of 1879 incorporated a frame of steel carrying masonry infill that, Thomas argues, predates similar systems in Chicago and suggests an alternative history to the modernist emphasis on the Midwestern origins of skeleton construction.

As a final session of our fall semester, Museum Director Carol Willis offers an overview of the themes explored in the series and proposes a set of characteristics to define “skyscraper” that includes 21st-century developments. She argues that looking backward from today makes clear that a standard definition that cites “steel skeleton” is woefully outdated and proposes some key characteristics that have defined the skyscraper typology across the past 150 years.

The standard narrative of the birth and development of the skyscraper has always stressed steel replacing masonry. But today, concrete is employed in a range of structural systems and a heavy concrete core is the standard feature of all supertalls. The engineer of the next world’s tallest building (if completed) Jeddah Tower, describes its structure a “pure bearing wall.”

A better definition of the skyscraper and its history uses more lenses than a focus on materials, technology, and structural systems, as our series of speakers have demonstrated in their talks. But there is a fixation on certain questions in the popular press and even in scholarship such as the recent publication of the Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat (CTBUH) titled First Skyscrapers | Skyscraper Firsts.

“What was the first skyscraper?” presupposes we know what a “skyscraper” is. Willis will attempt to frame some of the points of a definition and discussion for a continuing dialogue.

Readings

Carol Willis, “Fractious Firsts,” in First Skyscrapers | Skyscraper Firsts, CTBUH, Chicago, 2020.

Speaker Bios

Andrew S. Dolkart is a Professor of Historic Preservation at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation. His books, which highlight New York City’s everyday, vernacular building types, include Morningside Heights: A History of Its Architecture and Development (Columbia University Press, 2001), Biography of a Tenement House in New York City: An Architectural History of 97 Orchard Street (Center for American Places at Columbia College, 2012), and The Row House Reborn: Architecture and Neighborhoods in New York City 1908-1929 (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009). He was the guest curator for the Museum’s 2012 exhibition Urban Fabric and it working on a book on New York’s Garment District.

Gail Fenske is author of The Skyscraper and the City: The Woolworth Building and the Making of Modern New York (University of Chicago Press, 2008) and co-editor of Aalto and America (Yale University Press, 2012). She is Professor of Architecture in the School of Architecture, Art & Historic Preservation at Roger Williams University and has taught as a visiting professor at Cornell, Wellesley, and MIT. She is also a licensed architect and has practiced architecture in Boston and New York. She holds a Ph.D. in the history, theory, and criticism of architecture from MIT.

Richard Haw is Associate Professor of Interdisciplinary Studies at John Jay College of Criminal Justice, CUNY. He is the author of Engineering America: The Life and Times of John A. Roebling (Oxford University Press, 2020) as well as Art of the Brooklyn Bridge: A Visual History (Routledge, 2012) and The Brooklyn Bridge: A Cultural History (Rutgers University Press, 2008).

Donald Friedman, a structural engineer, is the president of Old Structures Engineering and author of several books, including Historical Building Construction (1995, rev. 2010). His 2014 study “Structure in Skyscrapers: History and Preservation” was the inspiration for the exhibition TEN & TALLER, 1874-1900. His upcoming book, The Structure of Skyscrapers in America, 1871-1900: Their History and Preservation surveys the development of high-rise buildings across the country in the last decades of the nineteenth century (Association for Preservation Technology, 2020).

Lee Gray is Professor of Architectural History and Senior Associate Dean of the College of Arts + Architecture at UNC Charlotte. An expert on early commercial buildings and elevator history, Gray is the author of From Ascending Rooms to Express Elevators: A History of the Passenger Elevator in the 19th Century (Elevator World Inc., 2002). He has written monthly articles on the history of vertical transportation for Elevator World Magazine since 2003. New York’s Tribune Building was a focus of his dissertation, “The Office Building in New York City, 1850-1880” (Ph.D. diss., Cornell Univ., 1993). He is currently writing about the history of escalators and moving sidewalks.

Kathryn Holliday, Professor of Architectural History in the School of Architecture at University of Texas Arlington, is an architectural historian of American architecture in the 19th and 20th centuries. She is the author of Leopold Eidlitz: Architecture and Idealism in the Gilded Age (W. W. Norton, 2008) and Ralph Walker: Architect of the Century (Rizzoli, 2012). Her current research focuses on a history of telephone buildings since the invention of commercial telephone service by Alexander Graham Bell in 1876, titled “Telephone City” and an examination of the postwar boom in architecture in the suburban landscape of Dallas and Fort Worth in the 1960s and 1970s.

Thomas Leslie is the Morrill Pickard Chilton Professor in Architecture at Iowa State University where he researches the integration of building sciences and arts, both historically and in contemporary practice. He is the author of Chicago Skyscrapers, 1871-1934 (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2013), and is currently writing its sequel Chicago Skyscrapers, 1934-1985. A winner of the 2013 Booth Family Rome Prize in Historic Preservation and Conservation at the American Academy in Rome, he is also at work on a study of the Italian engineer and architect Pier Luigi Nervi.

Joanna Merwood-Salisbury is Professor of Architecture at Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand. Her research on 19th-century American architecture and urbanism has a particular emphasis on issues of race and labor. Her publications include Design for the Crowd: Patriotism and Protest in Union Square (University of Chicago Press, 2019) and Chicago 1890: The Skyscraper and the Modern City (University of Chicago Press, 2009).

A.K. Sandoval-Strausz is Associate Professor of History at Penn State University where he directs the Latina/o studies program. The winner of numerous grants and academic awards, he is the author of Barrio America: How Latino Immigrants Saved the American City (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2019) and Hotel: An American History (Yale, 2007), which was named a Best Book of that year by Library Journal. With Nancy Kwak, he is co-editor of Making Cities Global: The Transnational Turn in Urban History (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2017).

George E. Thomas is a principal in a Philadelphia consulting practice of CivicVisions, LP and is co-director of the Masters in Design Studies program in Critical Conservation in the Graduate School of Design at Harvard University. His most recent publication, Frank Furness: Architecture in the Age of the Great Machines (2018) won the Victorian Society in America’s book award for 2019

Carol Willis is the founder, director, and curator of The Skyscraper Museum. She is the author of Form Follows Finance: Skyscrapers and Skylines in New York and Chicago (Princeton Architectural Press, 1995), among other publications. An Adjunct Associate Professor of Urban Studies at Columbia University's GSAPP, she teaches in the program Shape of Two Cities: New York and Paris.

HOW TO REGISTER

Rewriting Skyscraper History has been conceived as a free college course that will be presented as a live webinar and also recorded for future use. Every session will be quickly posted and archived on the series page, where there will also be a syllabus of related readings and resources. We recommend following the series in sequence as an unfolding "semester" of ideas and themes.

The sessions are live webinars that allow for discussion among the speakers and the audience. Members can sign up for the entire course of lectures. Non-members must sign up for each individual program. All lectures are streamed live via the platform GoToWebinar. The sessions are capped at 150 attendees.

Members receive priority for reserved spots and can register for the entire series or single events by emailing [email protected].

If you are not a member of The Skyscraper Museum, you must register for each event separately by clicking the RSVP button.

Want to become a member? Click here!