In the recession of the 1990s, and even before, savvy American and New York-based architects and engineers cultivated Asian commissions and established important client relationships that continue today. A panel of principals who pioneered their Asian practices recount the circumstances of their early commissions, illustrate recent projects, and reflect on the relevance for today.

Speakers

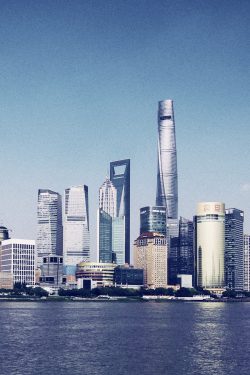

Robert Ivy, editor in chief of Architectural Record, introduced October 13th’s program with his own experiences in Shanghai, a city that he describes as “centrifugal… a city that is both centered on a nucleus and spreading out in a circular pattern, a regular pattern, ultimately of nine outlying cities from the core.” The four speakers that evening had created a collection of some of the finest tall buildings in the world in a new city that has a sense of authenticity, of “rightness.”

Bruce Fowle‘s first trip to China was in 1992 during the economic downturn in New York. His photographs of the various architectural types seen within the fabrics of Shanghai and the vibrant street life, such as the “lava of bicyclists.” He described some of the early FXFOWLE projects in Shanghai, within the time and place context of a frivolous early generation of tall buildings and the brutalist approach to urban planning.

John C. Portman III‘s Shanghai Centre established not only a geographic landmark for taxi drivers to communicate with foreign tourists, but as Jack Portman explained, this mixed use urban development acted as a facilitator for other foreign companies to develop in China and therefore had a significant impact on the growth of the city. The 2 million square foot office and hotel complex is the largest foreign investment project in China, completed in 1990. Jack described his feelings in 1969, when looking across the border to China from Hong Kong, seeking the romanticism and mystery of China, specifically Shanghai, during a time that it was forbidden. He established the firm’s Shanghai office in early 1993, and he remains involved in all Portman projects in China. Jack compared the firm’s current project, which will preserve shikumen housing in creating retail and hotel space with condominiums, in historic On Shui to the city’s token adaptive re-use project, Xintiandi, which will be discussed by its architect, Ben Wood, on November 24.

David Scott Next to Shanghai Centre is Arup’s first project in Shanghai, completed in 1984. Principal David Scott described the startling difference in pace between work in New York and work in Shanghai, which he noticed upon arriving there in 1985. He continued to describe the differences in the engineering practice in China, primarily the elimination of consultants and the order in which the parties communicate. The projects now focus on energy consumption while building with high density. He illustrated the structural system of the Shanghai Hilton, with its concrete core, steel frame, and outrigger system that created a standard and lightweight approach. Currently, Arup is working on two pavilions for the Shanghai 2010 World Expo.

Jamie von Klemperer expressed the importance of Arup’s work, as it “holds up the work of KPF and Portman.” Recounting Kohn Pedersen Fox’s entrance in the Shanghai market, Jamie explained that their “first wave” was in Hong Kong and Tokyo (western-influenced Asian markets). Once again referencing the Portman Center, Jamie described the adjacent Plaza 66, the tallest building in Puxi. With its “holy grail” Louis Vuitton store, Jamie joked that the designer drives entire development projects. Across the Huangpu River, Jamie described the tallest building in Pudong, developed by the Japanese Mori Company. The graceful form peaks at the highest occupiable space in the world. The next, and third, wave of work is Jamie’s project the JingAn Kerry Center in Puxi, a mixed-use complex with hotel, office, and retail and connection to subways. Instead of a large podium, typical of mixed-use skyscraper projects, the complex is bisected by public space and pedestrian veins from the major shopping street, Nanjing Lu. Jamie illustrated the amount of work completed in Shanghai in the context of Manhattan -when lined up shoulder-to-shoulder, the KPF Shanghai buildings would stretch from the Empire State Building to Central Park.

The four sat down with Bob Ivy for a discussion, to tie together the stories of their first experiences and the issues already illuminated in the design, financing, and construction processes. Despite the lack of contractual structure, the firms represented have contributed to creating a sophisticated environment now in place to conduct business and continue building the skyline of Shanghai.