On May 1, 1997, The Skyscraper Museum opened a major exhibition on the architecture and urbanism of Lower Manhattan in donated space, a vacant banking hall at 44 Wall Street, a 1926 skyscraper in the heart of New York’s financial district.

Times Square today is bright and crowded – a tourist mecca, entertainment district, retail powerhouse, and pedestrianized precinct that matches in vitality, both economic and populist, any decade of its storied past. But thirty years ago, the future of Times Square was in limbo – caught between a series of false starts at clean-slate urban renewal by the City and State and an emerging philosophy of urbanism that favored history, preservationist values, electric signs and semiotics, and delirious diversity.

Eighty thousand incandescent bulbs illuminated the New York night on April 24, 1913, when the Woolworth Building opened with a ceremony attended by 800 dignitaries. Witnessed by multitudes and wired to press around the world, the brilliant spectacle was a career-crowning achievement for the tower’s owner, the five-and-dime store king Frank W. Woolworth, who paid for the skyscraper with his personal fortune and took a hands-on role in every decision of its design. The great Gothic tower-the Cathedral of Commerce-became the preeminent silhouette on the New York skyline and took the title of world’s tallest office building.

The largest concentration of skyscraper factories in the world, the 18 blocks that were the heart of New York’s Garment District, once supported more than 100,000 manufacturing jobs and produced nearly 3/4 of all women’s and children’s apparel in the United States. The rapid development of the district–the area of west midtown from 35th to 41st Streets and from Seventh to Ninth Avenues–occurred almost entirely within the boom decade of the 1920s, when more than 125 stepped-back “loft” buildings took the pyramidal forms dictated by the city’s new zoning law.

The first chapters in New York’s high-rise history were written in the 1870s through the early 1900s when the city’s great newspapers –the Times, Tribune, and World, among others– erected tall towers as signature headquarters. “Newspaper Row” on the east side of City Hall Park was center stage for their architectural competition and a concentrated hub of production, transforming news into newspapers. These early skyscrapers were both ostentatious advertisements of the papers’ self-proclaimed supremacy and vertical factories where on high floors, editors approved stories and compositors set type, while in the cellar and basement, steam engines or dynamos powered thundering presses that night and day rolled out tens of thousands of papers per hour.

From colonial times, when the first bastions were erected to mark the edge of town, Wall Street has been continuously transformed, both in function—from commercial and residential to financial—as well as in scale. Row houses were replaced by low-rise banks, then massive high-rise office buildings. The skyscrapers that line Wall Street today represent the climax species of an intense urban process that the exhibit documents with graphics of successive buildings on a given site since 1850. These “Vertical Wall Street” images dramatically illustrate the cycles of growth that shaped the financial district over time, charting both the evolution from small to tall and the growing girth of buildings enabled by new technologies and slow, but savvy site assembly.

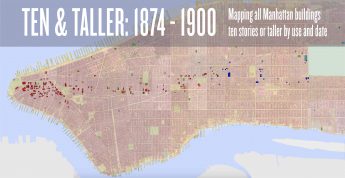

As part of the FUTURE CITY 20|21 cycle of three exhibitions, NEW YORK MODERN looked back at prophecies of the skyscraper city in the early 20th century when the first dreams of a fantastic vertical metropolis took shape. From the invention of the tall office building and high-rise hotels in the late 19th century, New York began to expand upward, and by 1900, the idea of unbridled growth and inevitably increasing congestion was lampooned in cartoons in the popular press and critiqued by prominent architects and urban reformers.

What are your Top Ten favorite New York skyscrapers? That question was posed in a Skyscraper Museum survey completed by an invited list of 100 knowledgeable New Yorkers and building industry professionals, including architects and engineers, developers, brokers, builders, historians, and critics. The results were seen in this exhibition.

City of Change explored the role of the skyscraper in shaping the identity and character of downtown’s streets and skyline. Linking past, present, and future, the exhibit examined the construction of the World Trade Center and the rebuilding at Ground Zero and highlighted the new construction and residential conversions underway throughout the district.

Inspired by the popularity of the museum’s 2000 spring lecture series, Times Square Now, the installation explored the interactions of design and development by showing the evolution of the building form through multiple study models

Through taking an unconventional look at high-rise size. The exhibition introduced Jumbo and Super Jumbo buildings, categories that describe size as measured by volume.

Building the Empire State examined the design and construction of New York’s signature skyscraper, drawing together photographs and film of the construction, architectural and engineering drawings, contracts, builders’ records, financial reports, and other artifacts.