NEW YORK CITY

New York City produced the first supertall, our benchmark Empire State Building, at the end of an unprecedented boom in high-rise office construction in the late 1920s that added more than a dozen towers of 40 to 50 or more stories to the skyline. The Empire State was not a typical tower of 600 to 800 feet: its 86th floor leveled off at 1,050 feet and the tip of its mooring-mast spire reached the altitude of 1,250 feet/ 381 meters. Not only was the Empire State 50 to 25 percent taller than its contemporaries, it was more than twice as big in its floor area – 2.1 million sq. ft. (as measured at the time: now 2.6 million), in contrast with the 900,000 sq. ft. of the Chrysler Building.

Floor area was as decisive a factor as height in the 1960s and ‘70s when each of the twin towers of the World Trade Center independently qualified as the world’s largest building (with a floor area of 4.5 million sq. ft.), as well as, briefly, the world’s two tallest buildings at 1,363 and 1,368 feet. The Sixties was a period of gigantism in the scale of its towers that was not matched until the Chinese supertalls Ping An (2017) and CITIC, Beijing (2018).

New York developers erected many new skyscrapers in the later 20th century, but no supertalls. This was largely because the 1961 zoning laws restricted the maximum size of towers by a Floor Area Ratio (FAR), a formula geared to the area of the lot and the type of “use” district. Thus, to erect an office building that was taller than around 800 feet and 55 stories required a very large site – rare in Manhattan – and special allowances for bonus FAR or transferred development rights. When the World Trade Center was destroyed on 9/11/2001, the Empire State once again became the tallest building in the city.

In the aftermath of the terrorist attacks, many predicted the end of skyscrapers, opining that people would be too nervous to live or work in tall towers and that lenders would decline to finance them. Those predictions were short-lived, especially in other parts of the world, but soon also in New York. Today, less than two decades after 9/11, there are six new towers taller than the Empire State Building on the Manhattan skyline – the largest number of supertalls of any city in the world.

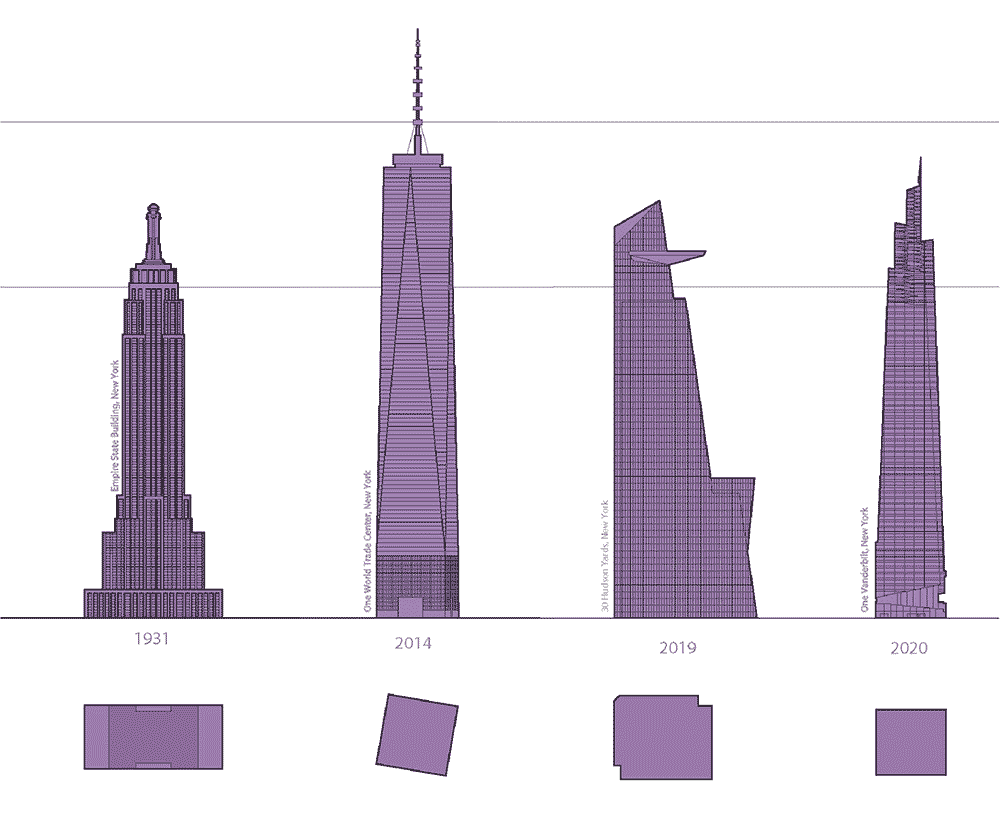

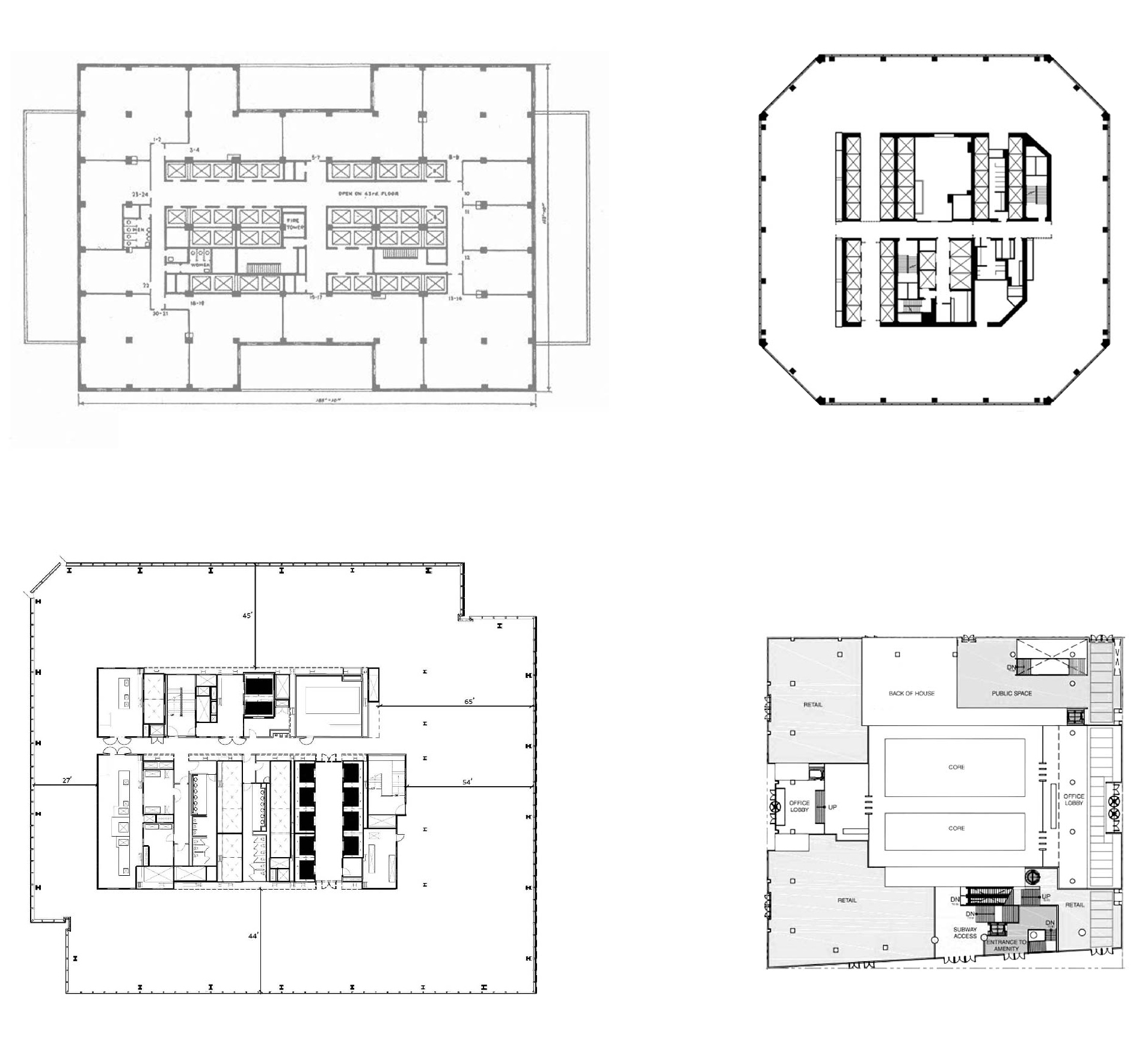

OFFICE

Since the completion of One World Trade Center at the Ground Zero site in 2014, Manhattan has seen a resurgence of supertall office buildings in Midtown, with One Vanderbilt, topped out in 2019, and 30 Hudson Yards (2019) in Far West Midtown. Others are planned for the district that was up-zoned by the City in 2017 to allow more FAR in a 73-block area called East Midtown that surrounds Grand Central Terminal and extends north in broad swath centered on Park Avenue to 57th Street. This includes the new headquarters for JP Morgan Chase to be erected on the site of the classic postwar glass box at 270 Park Avenue, designed for Union Carbide by SOM in 1957, under demolition in 2020.

As can be seen in the relation of elevation silhouettes and the typical floor plans above, all to the same scale, the office towers have large footprints at street level and spacious upper floors arranged around a robust central core built of thick walls of reinforced concrete. The only building with a different plan and structural system is the 1931 Empire State, which uses its twentieth-century steel-skeleton construction in a uniform grid of columns that intrude on the open space of the interior. The multiplicity of elevator banks rise within the steel frame. In the twenty-first century towers, the office floors are open plan, providing as much uninterrupted space, and views, as possible.

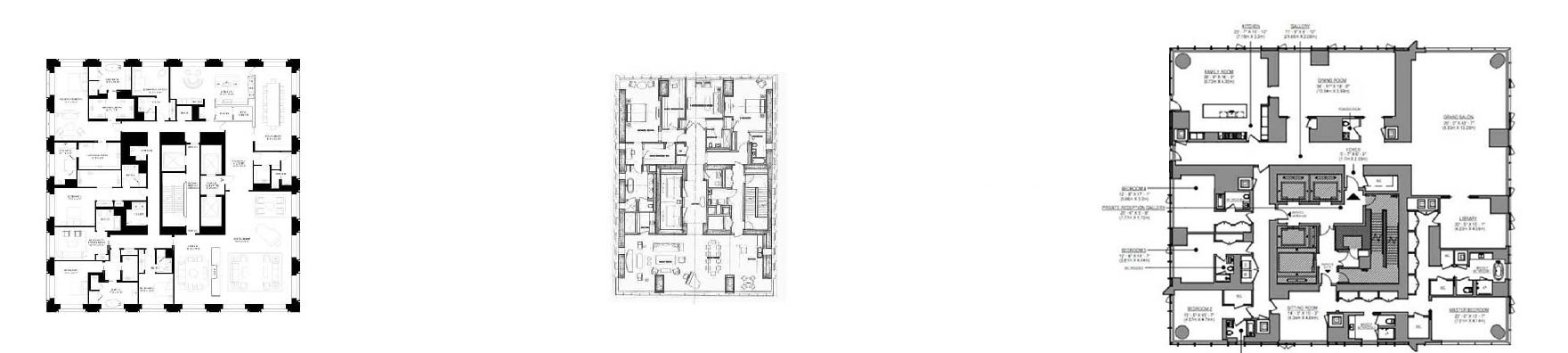

RESIDENTIAL

The first round of new construction – which began around 2008, but was stalled by the Great Recession – was residential. Developers, architects, and engineers invented a new typology: the super-slender, ultra-luxury, condominium tower. These thin reeds use air rights purchased from under-developed neighbors to add extra stories to small lots at high-value locations, such as the southern edge of Central Park and West 57th Street, which acquired the moniker Billionaire’s Row. With a slenderness ratio of at least 10:1 – and in the case of 111 W. 57th Street, an astonishing 23:1 – these buildings represent a true innovation in skyscraper history.

The development strategy of these super-slender towers is to squeeze as much of the valuable, purchased FAR into a very small footprint and to raise each floor of apartments (usually only one, or perhaps two, apartments per floor) as high in the sky as possible to capture spectacular views. Because of the small number of units overall, the elevators can be reduced to two to five shafts – unlike an office building that requires many banks for efficient vertical transit – thus also keeping the ratio of saleable floor area to the mechanical core highly profitable for the developer. This strategy is fully explained in the Museum’s 2013 exhibition SKY HIGH & the Logic of Luxury.