INTRODUCTION

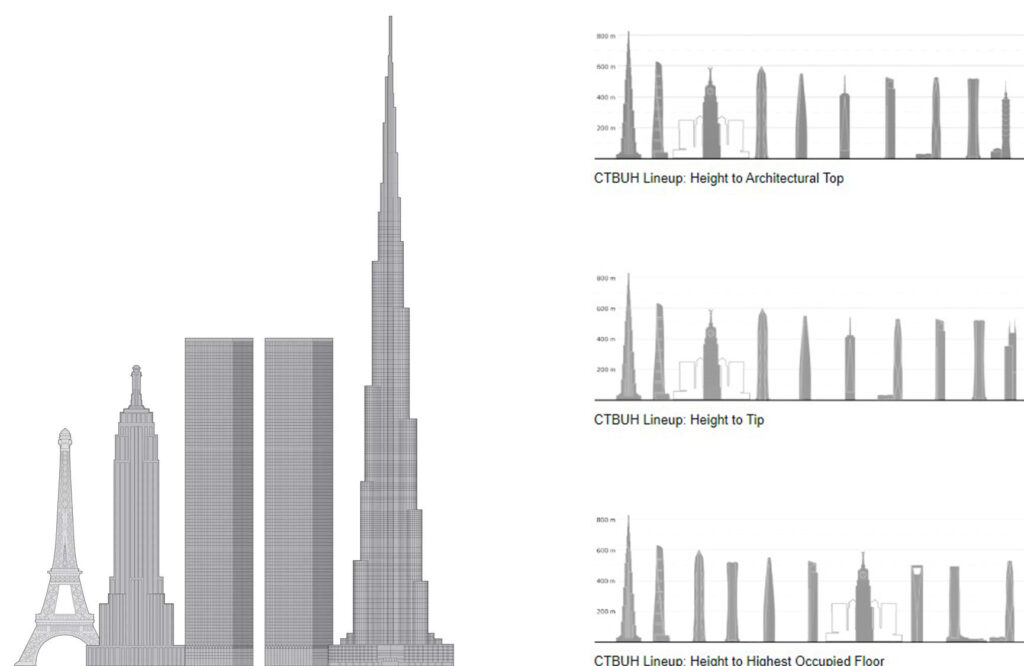

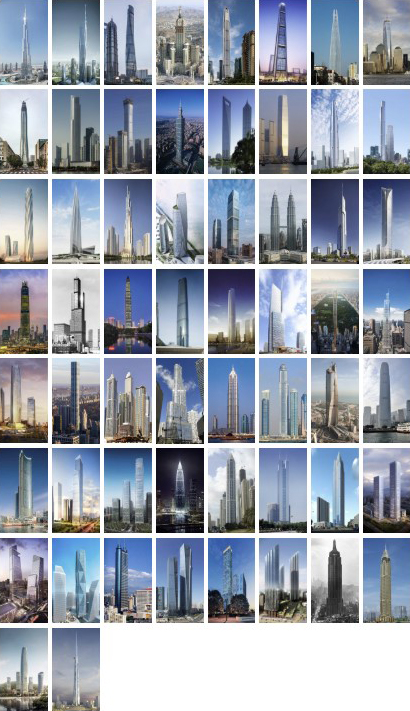

How tall is Supertall? The Skyscraper Museum sets its bar high: 1,250 feet/ 380 meters, the height of the Empire State Building. The popular benchmark of 300 meters – about 1,000 feet – favors round numbers, but represents a 19th-century standard, the Eiffel Tower. Skyscrapers began to exceed 300 meters only in the late 1920s in New York City, where the Chrysler Building and Empire State were the only structures of that height until the World Trade Center in the 1960s. Today, 300 meters is fairly common, with more than 200 buildings of that height worldwide. But towers of 380 meters remain exceptional: our survey counts only 58.

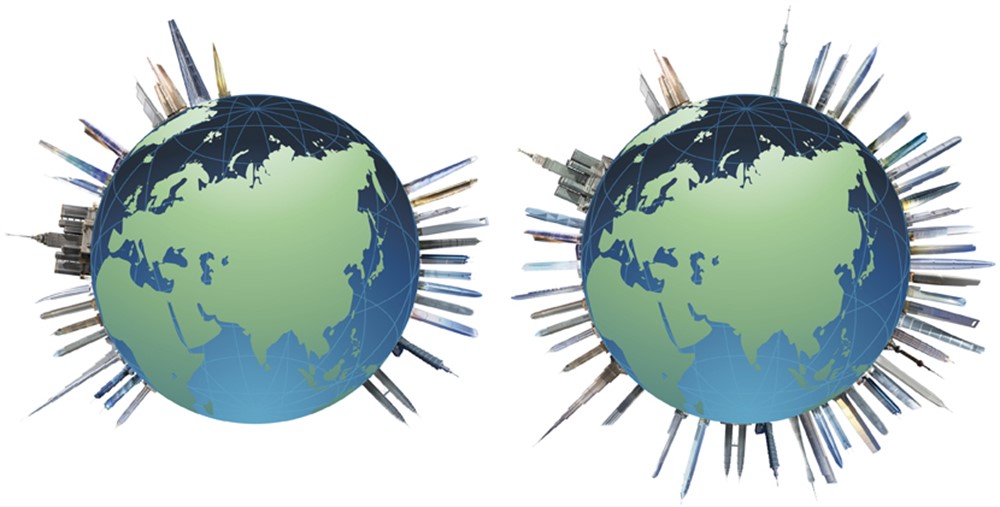

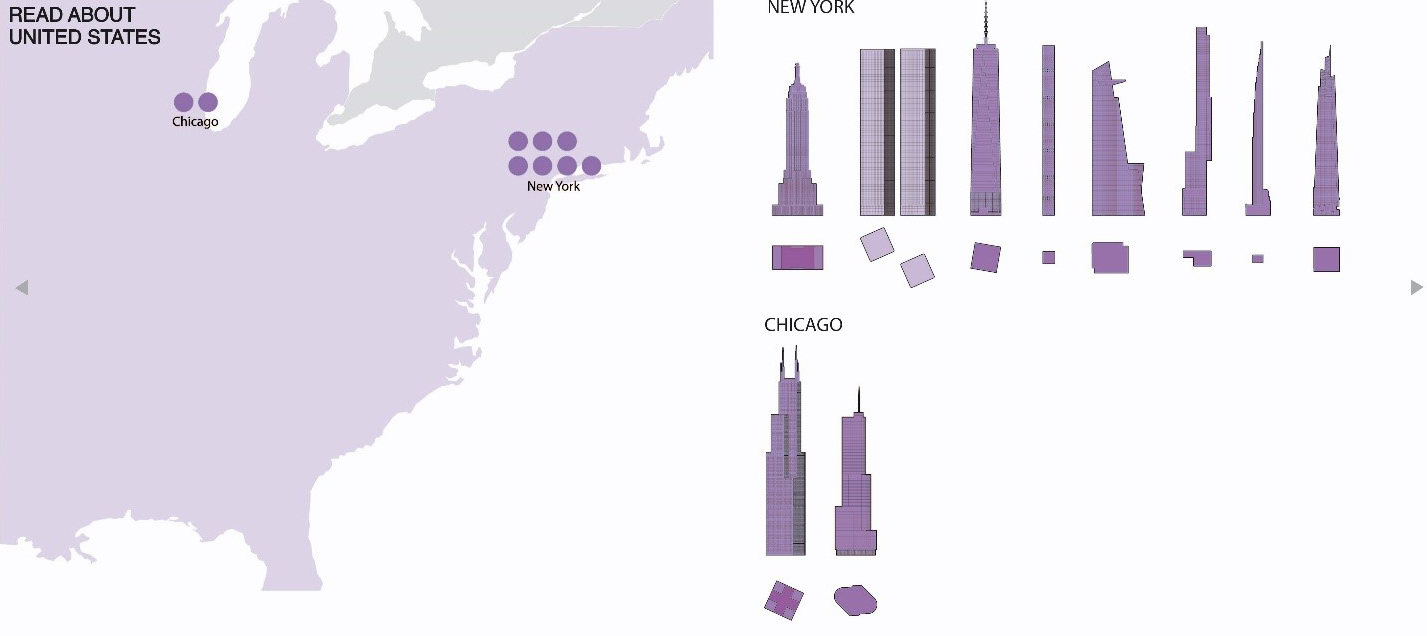

Where are the world’s tallest buildings today? The early 2000s saw a surge in international construction, especially in the emerging economies of the Middle East and China. In Dubai, the Burj Khalifa, completed in 2010, stretched to 2,717 feet/ 828 meters. China dominates all countries with 30 supertalls in sixteen different cities. Southeast Asia is emerging as a sphere of ambition, and Russia completed Europe’s first supertall. In New York, where after 9/11 many believed there would be no new skyscrapers, there are now six towers taller than the Empire State, the most of any city on the planet.

A contest for superior height is not the driving force in all these projects, although status and commanding views clearly are important. Supertalls are expensive and exceptional buildings, but they are also now well established as 21st-century type. The exhibition features about a dozen of the most extraordinary recent towers, exploring ideas about formal and structural innovation, as well as the place of a signature tower in a master-planned, mixed-use complex that creates community and value on both the ground and in the sky.

HISTORY

Only one structure in world history – the Eiffel Tower – had achieved the height of 1,000 feet/ 300 meters before 1929, when the Chrysler Building reached its spire to 1,046 feet and 1930 when the Empire State stretched to 1,250 ft., our determinant of supertall.

At the 1889 Paris Exposition Universelle engineer Gustave Eiffel constructed the then-controversial, but now beloved wrought-iron tower as an income-producing tourist attraction and a demonstration of France’s technological progress. At 300 meters it was almost twice the height of the tallest structures of any era – the ancient Egyptian pyramids, the tallest cathedral spire of Europe, or the tallest in the world in 1884, the 555-foot tall Washington Monument – all of which were built of masonry.

The history of building height is most often told as a story about the competition for the world’s tallest structure. The title was taken from France by American skyscrapers in the mid-twentieth century, then by Malaysia, Taiwan, and Dubai in the United Arab Emirates, where it still resides in the 828 meter Burj Khalifa, an extraordinary structure more than two Empire State Buildings tall.

The exhibition SUPERTALL! 2020 does not emphasize the issue of “tallest,” and especially not in the sense of judging parts of the building to count or how different measures reorder the ranking of structures. That is the province of the Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat (CTBUH), which maintains an exemplary online database in their Skyscraper Center and vets the various official measurements of vertical height and lists of the world’s tallest buildings.

The three different definitions that the CTBUH applies to measure and rank buildings by height, as shown in the adjacent charts, are:

1) Height to the “architectural top,” meaning the highest point of any part of the original design, including spires that can stretch 100 meters or more;

2) Height to the tip, or the highest point of any structure added at any time, such as an antenna;

3) Height to the highest occupied floor, according to CTBUH stated criteria “the finished floor level of the highest occupiable floor within the building.”

Comparing the charts, we can see that eight buildings remain the same across all three lineups and that the only switches in the list (both in the #10 position) are Taipei 101 for lineup 1 and Sears/ Willis Tower for lineup 2. The most notable misfit on these two charts is One World Trade Center, which stands in the sixth position for the world’s tallest building on both only by virtue of its more than 400-foot spire. One World Trade Center does not make it onto the “Highest Occupied Floor” list at all, nor do Taipei 101 or Sears/ Willis Tower.

Two towers – Shanghai World Financial Center and Two International Finance Centre in Hong Kong – appear only on the “Highest Occupied Floor” list. Both are substantial buildings in height and girth, so they seem to be much more similar to the others on this chart than the outliers on the other lists.

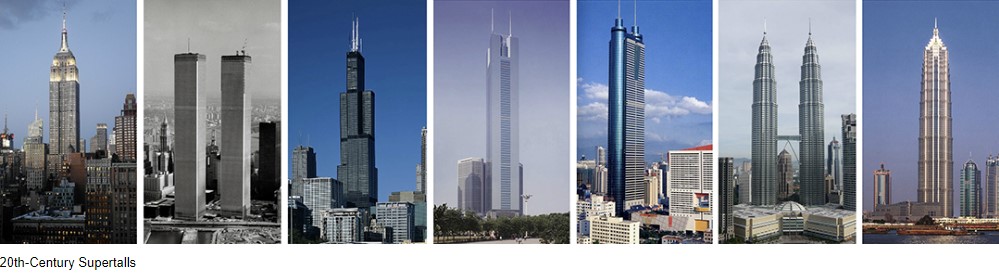

Twentieth-century Supertalls

Supertalls were rare in the 20th century. Although many were proposed, the only ones constructed by 1974 were the American four: the Empire State, the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center, and Chicago’s Sears Tower.

The first international supertalls were the office buildings erected in the booming cities of southern China's Pearl River Delta: Shun Hing Square in Shenzhen and CITIC Plaza in Guangzhou, both completed in 1996. The world took more notice, however, when in 1998 the twin Petronas Towers in the Malaysian capital of Kuala Lumpur took the title of "world's tallest building" away from the United States for the first time. The last of the 20th century's giants was Jin Mao Tower in Shanghai, which in its slender form, mixed-use program of offices and hotel, and concrete structure prefigured the typical 21st-century supertall.

THE HISTORY OF THE MUSEUM'S PAST SUPERTALL EXHIBITIONS

SUPERTALL 2020 tallies 58 buildings worldwide that are completed or can be finished by 2024. They are all pictured and profiled in the LINEUP and GRID. The history of The Skyscraper Museum's past SUPERTALL SURVEYS can be traced in links to archived pages of its past exhibitions.

As part of the 2007 exhibition World's Tallest Building: Burj Dubai, the Museum created its first SUPERTALL SURVEY of skyscrapers worldwide the measured 380 meters/ 1,250 feet or higher. Even as the destruction of the Twin Towers on 9/11 shocked the world, the early 2000s saw a surge in the international construction of supertalls, especially in the emerging Economies of the Middle East and China. Completed in 2010, the Burj Khalifa, still the world's tallest building, stretched to 2,717 feet/ 828 meters. American architects and engineers dominated these new arenas of development, exporting their expertise.

The first survey counted 28 supertalls completed or under construction, as well as a few we believed would rise, but never did.

In 2011, the Museum mounted the exhibition SUPERTALL!, which featured 48 buildings worldwide –either completed, under construction, or proposed and approved by local authorities– that exceed our benchmark of 380+ meters. The survey revealed the growing supertall ambitions in Asia, and especially China, and the Middle East. Of this second SURVEY, eight towers were not completed as planned.

A cumulative page of supertalls that were included in past surveys is archived here: https://old.skyscraper.org/WEB_PROJECTS/SUPERTALL_SURVEY/2018.html

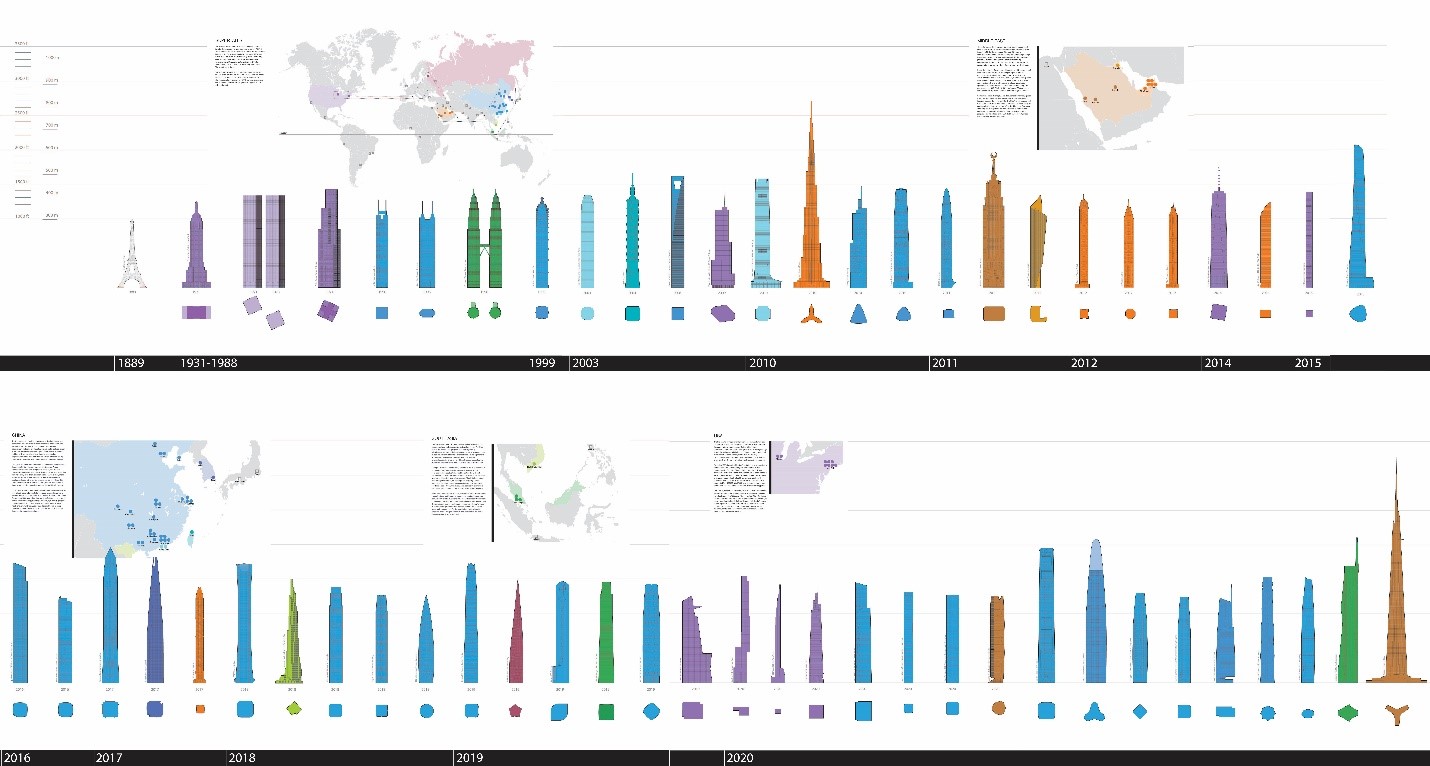

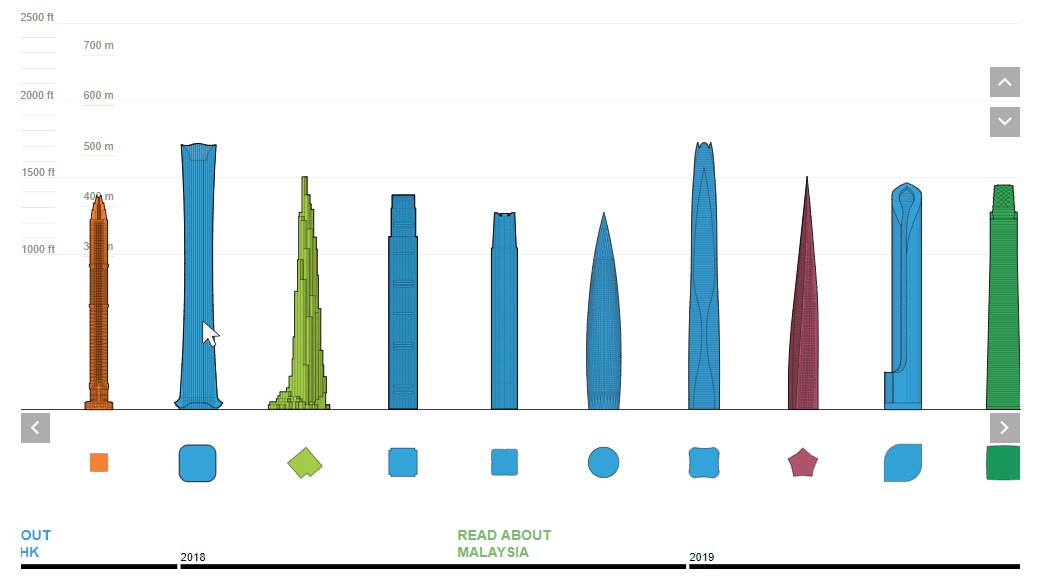

SUPERTALL LINEUP

The 58 towers on this chart are the tallest in the world today and include all skyscrapers either completed or under construction with a height of at least 1,250 feet/ 380 meters. The buildings are ordered by year of completion. Silhouettes are color coded by region. Use the MAP to view by country and city. CLICK on a building for details.

Skyscrapers, especially supertalls, are a “lagging indicator” of economic growth because they require at least five years to design and construct. Planned in boom times, they are often slowed or stalled by a downturn. We assume the towers here will be completed by 2024.

_____________________________________________________________________________

What can we learn from the Supertall Lineup? The first impression is the silhouettes simply measure height and describe a shape. Comparing heights on a vertical marker of meters or feet and picturing buildings by ascending height is probably the most common way to compare skyscrapers.

But these supertalls are ordered on a timeline by the year of completion. That tells us something different. If we see the timeline at one glance, we notice some patterns that reflect the influence of economic cycles and other regional influences. (Spurt of completions in the Middle East; Dominance of China, etc.). If we focus on a smaller sample and search for significance, we may notice that superior height is less important than what shape reveals – and especially the shape of the tower in relation to its plan, which is shown as a typical floor below the “ground line.”

When we click on a silhouette, a composite image with more information about the building pops up. This includes a map, photographs, renderings, drawings, and data.

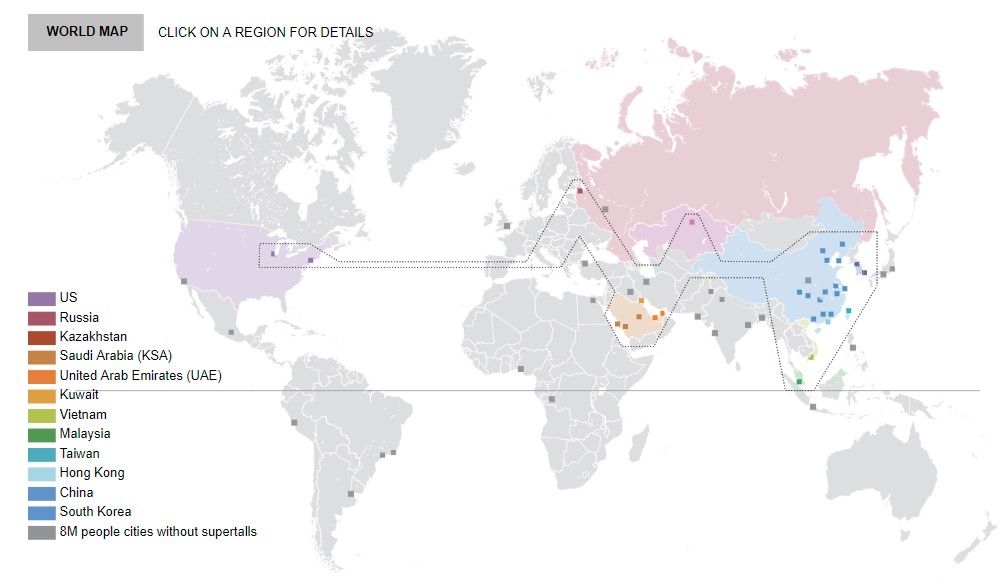

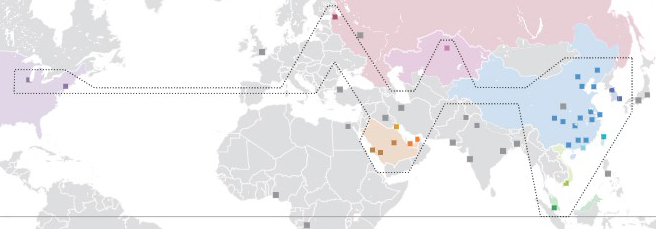

WORLD MAP

The world map shows the regions or countries with supertalls, and the colored squares mark cities with one or more supertalls. Gray squares represent selected cities with a population of at least 8 million –the size of New York – but with no supertalls. Click on a region to view a larger map with cities labeled and with dots indicating the number of supertalls, and see a narrative and lineup of the towers by city.

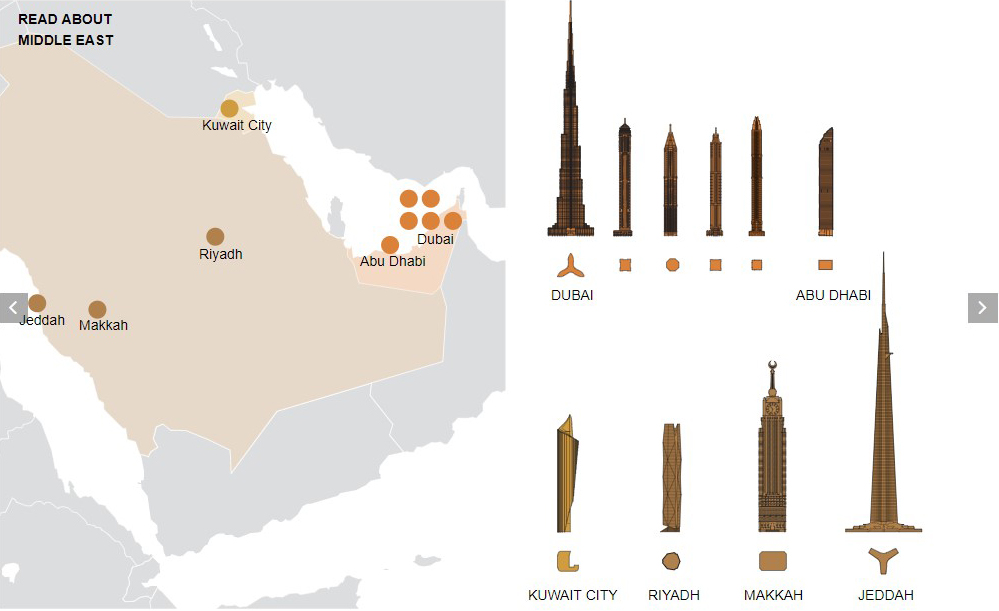

MIDDLE EAST

In the 1990s Dubai, a city-state in the United Arab Emirates with a population of only about 1.4 million and no oil of its own, began to position itself as the financial, commercial, and recreation center of the Gulf region Extravagant real estate ventures, such as the artificial Palm Islands in the Persian Gulf – visible from space – drove the economy. The most ambitious was the 163-story Burj Khalifa, which at 828 meters/ 2,717 feet, is by far the tallest structure on the planet. Principally residential, the tower includes corporate suites only on the top 37 stories. Dubai’s other four supertalls are all residential, as is the single example in Abu Dhabi.

In the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, both petrodollars and religion upped the scale of supertalls. Completed in 2012, the Makkah Royal Clock Tower, third tallest structure in the world, rises to 601 meters / 1,972 ft. to its crescent atop the Abraj Al-Bait complex of hotels, the Great Mosque, the Kaaba, and other pilgrimage facilities at Mecca. In nearby Jeddah, construction on the Kingdom Tower, now renamed Jeddah Tower, is stalled at about one quarter of its projected height of 1,000+ meters. The only other supertalls in the Middle East are office buildings in Riyadh and Kuwait City.

CHINA AND HONG KONG

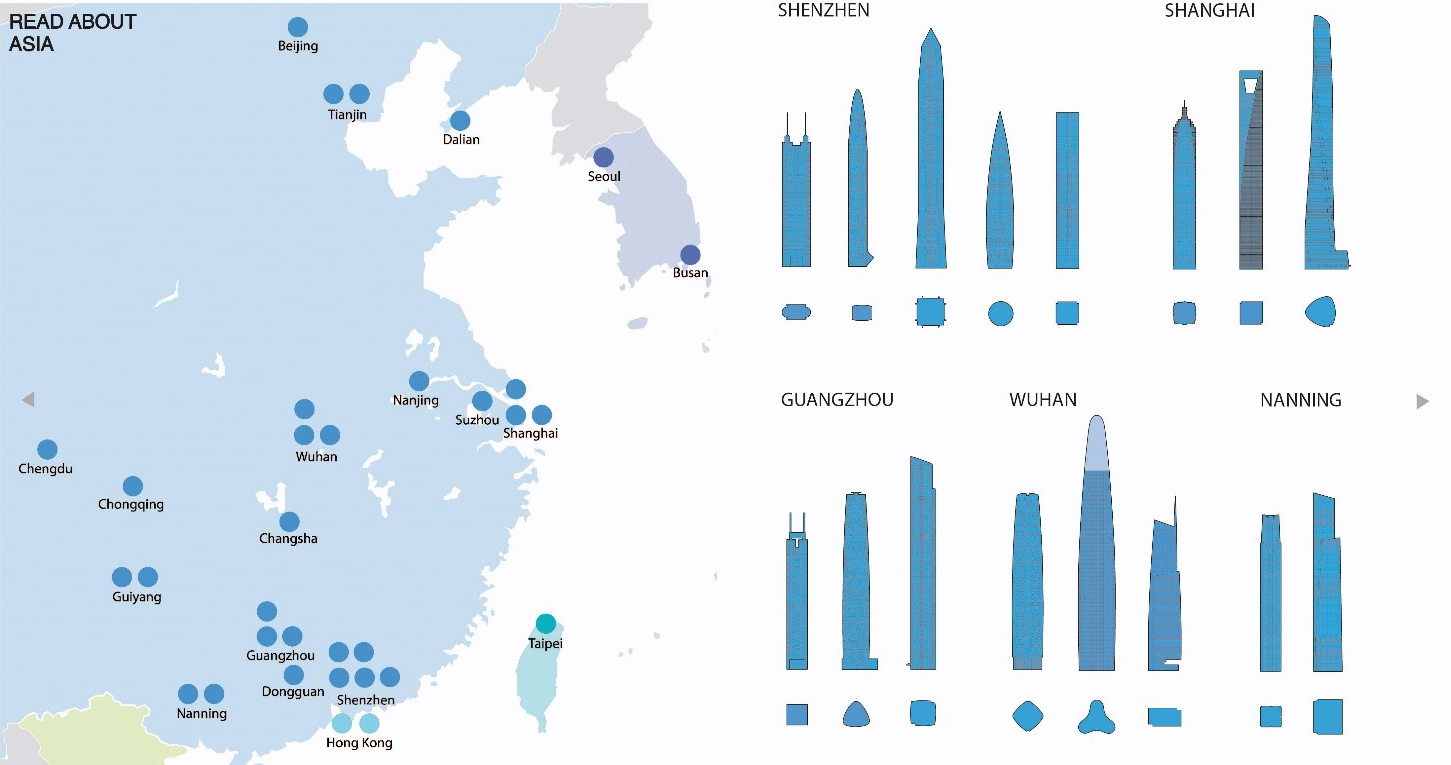

China, including Hong Kong, accounts for 30 of the 58 supertalls in our survey. The multiplication of supertalls and of skyscrapers generally in Chinese cities is the direct result of government policies of urbanization. From the 1980s, 340 million people – the equivalent population of the U.S. – moved from farms to cities in the largest mass migration in human history. The Chinese government encouraged and invested in new construction.

Beyond Hong Kong, which had long had a thriving skyscraper market, the first centers of supertall development focused on the financial district of Shanghai, as well as the fast-growing cities of the Pearl River Delta, Shenzhen and Guangzhou. Since 2007, many second- and third-tier Chinese cities with populations of four to twelve million, such as Chongqing, Chengdu, Dalian, Guiyang, Nanning, Nanjing, Tianjin, and Wuhan have built one or more major towers.

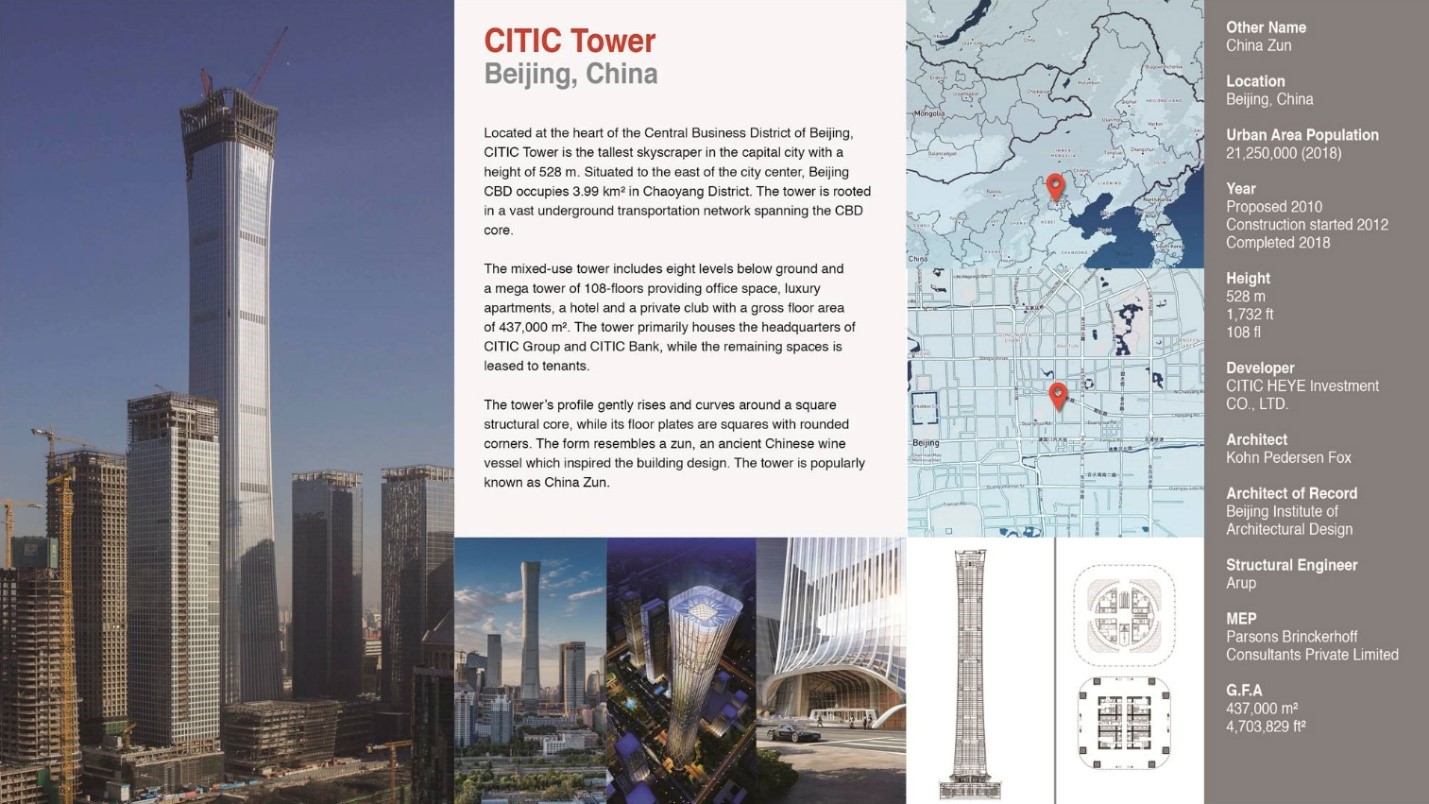

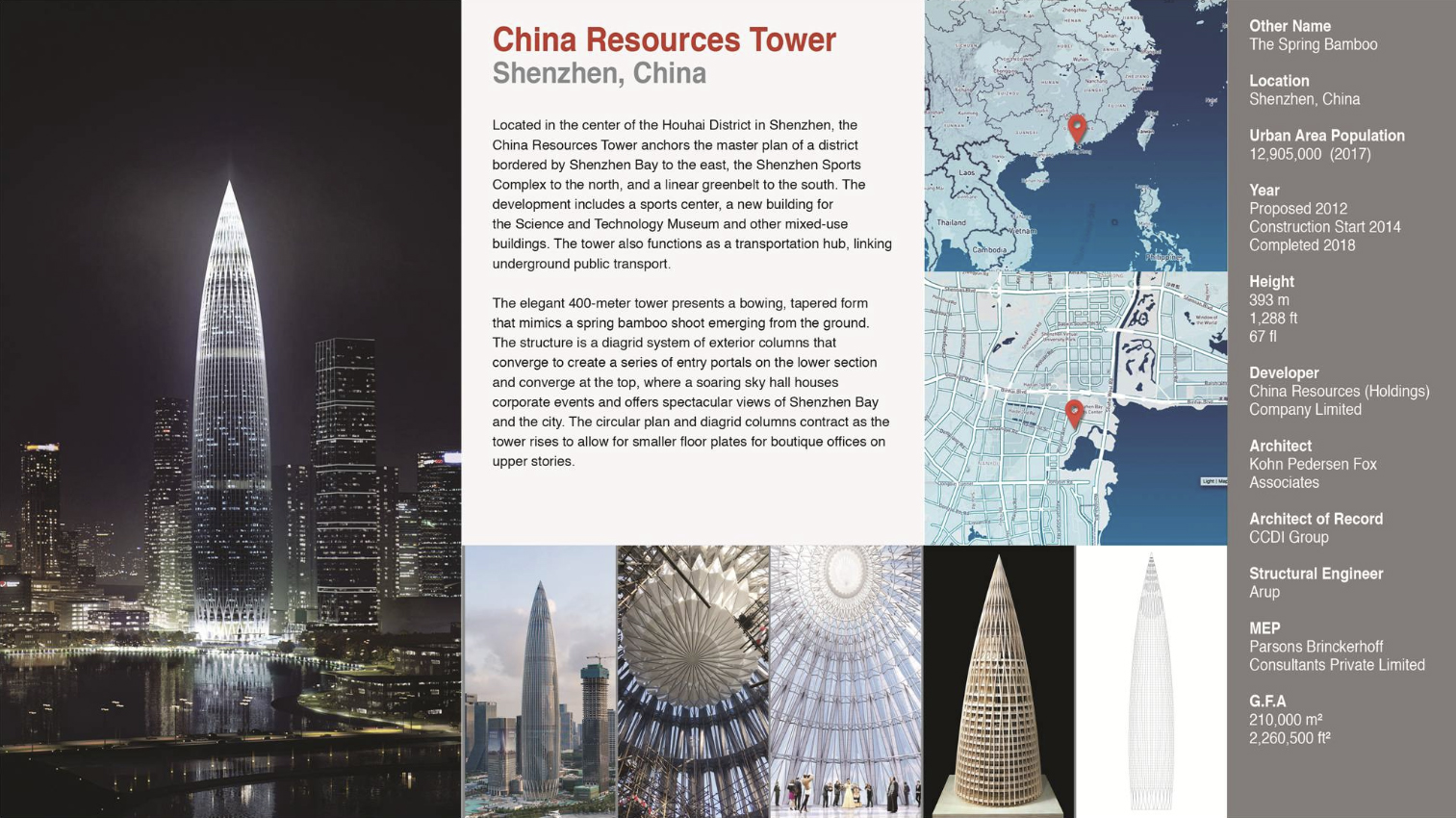

Chinese supertalls are most often mixed-use towers with offices on the lower floors and residences and hotels above. They are often simple, slender forms that taper toward the top, where floor-plates are reduced in size and depth for hotel floors. In headquarter office buildings such as CITIC Beijing and China Resources in Shenzhen, the topmost floors contain spectacular event spaces that also feature sweeping city views.

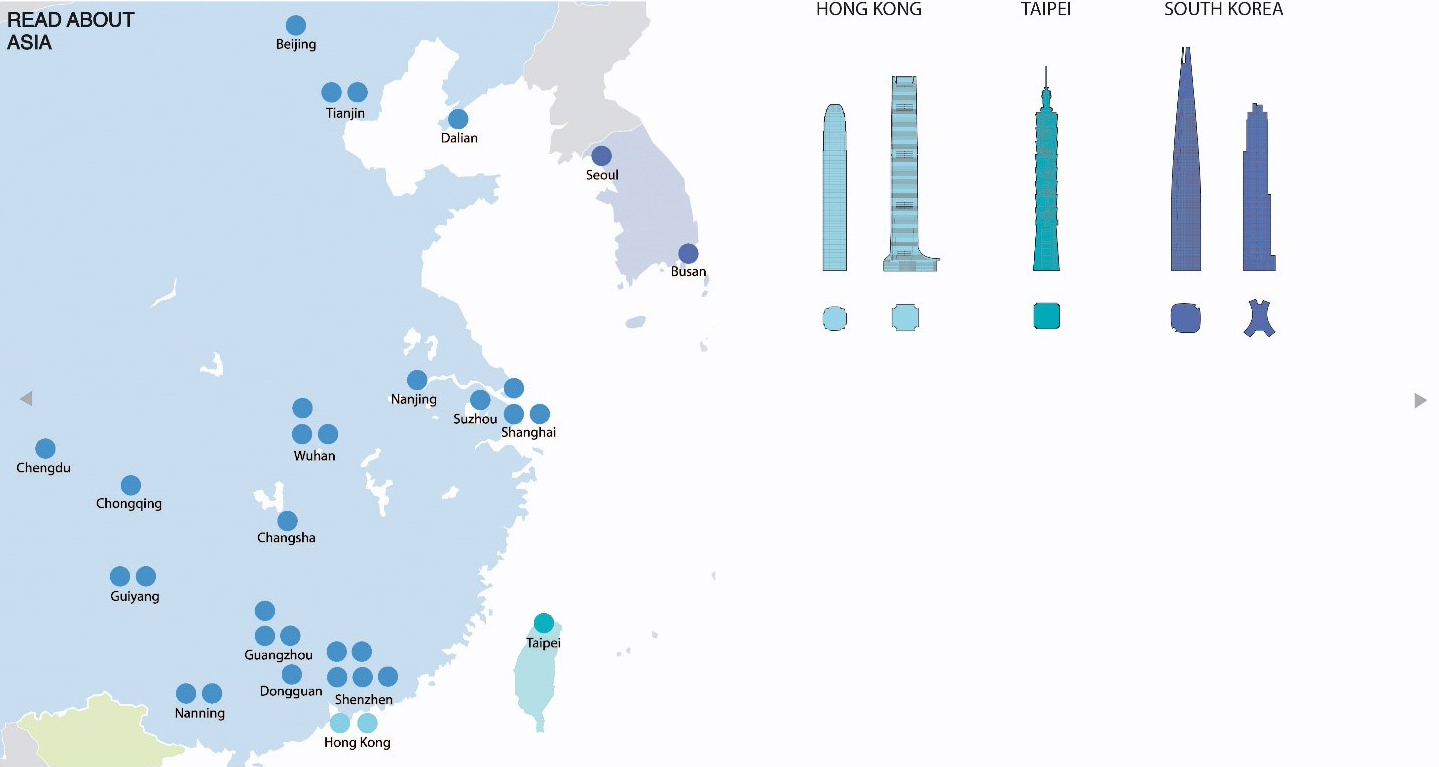

HONG KONG, TAIWAN, AND SOUTH KOREA

The high-rise is the characteristic architectural form of Hong Kong, which since the 1970s has had a very competitive culture of private development of both office buildings and residential towers. The first of Hong Kong’s two supertalls was Two International Finance Centre, was completed in 2003. It was surpassed in 2010 by the International Commerce Centre on the Kowloon side of the harbor.

The tallest building in Taipei, Taiwan, officially the capital of the Republic of China, is Taipei 101, which on its completion in 2004 took the title of world’s tallest building from the Petronas Towers in Kuala Lumpur and ceded it only in 2010 to Burj Khalifa. Today it ranks as only the tenth tallest.

Although Seoul, South Korea had plans for multiple supertalls in 2011, only two have been completed. At 123 floors, Lotte World Tower mixes office, residential, hotel, and retail functions with a seven-story observation deck. The other supertall in Busan is a beachfront hotel and residence of 101 stories.

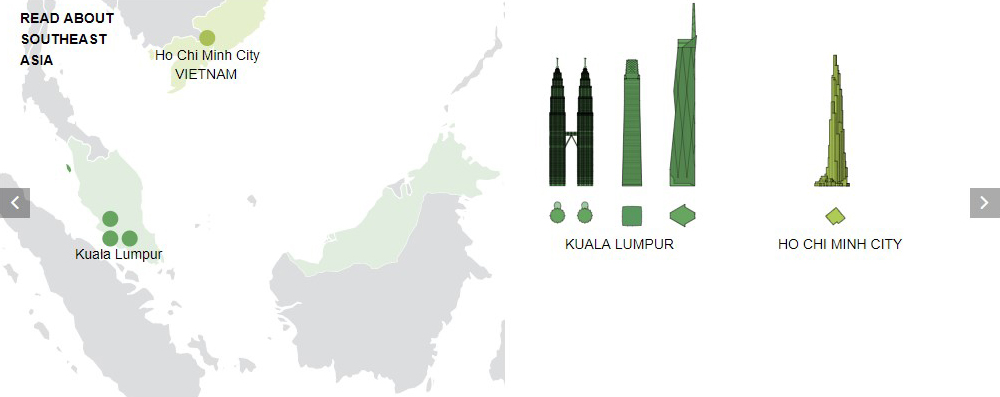

SOUTHEAST ASIA AND MALAYSIA

Kuala Lumpur grabbed the title of world’s tallest building from the USA in1998 with the completion of the twin Petronas Towers, and the fast-developing capital of Malaysia has continued to embrace the supertall as both a symbol and a strategy of urban development. Completed in 2019, Exchange 106 is the centerpiece of a government-sponsored new financial district and commercial complex. Now under construction, another complex on a site connected to national independence, Merdeka 118, will be the city’s tallest building and at 644 m/ 2,113 ft. to the point of its spire and will surpass Shanghai Tower to become the second-tallest building in the world.

The only other supertall in Southeast Asia is Vincom Landmark 81 in Ho Chi Min City. Completed in 2018, it is an 81-story mixed-use tower of multiple setbacks that is the signature structure of a residential development called Central Park.

USA

After 9/11, many predicted there would be no new skyscrapers built anywhere – and especially not in New York. It is therefore all the more remarkable that the city now has six supertalls towers – the largest number of any city in the world.

The first round of new construction, beginning around 2009, but stalled by the Great Recession, was residential. The super-slender, ultra-luxury apartment tower, used transferable air rights to add extraordinary height to small lots at high-value locations. With an engineering slenderness ratio of at least 10:1 – and with 111 W. 57th Street, an astonishing 23:1 – these buildings represent a true innovation in skyscraper history. Since the completion of One World Trade Center at the Ground Zero site in 2014, Manhattan has also seen a resurgence of supertall office buildings in Midtown, with One Vanderbilt at Grand Central Terminal and others planned for Park Avenue, and at Hudson Yards.

Chicago, the only other city in North America with supertalls, added one tower in 2009 that stretched its spire to 1,389 ft.

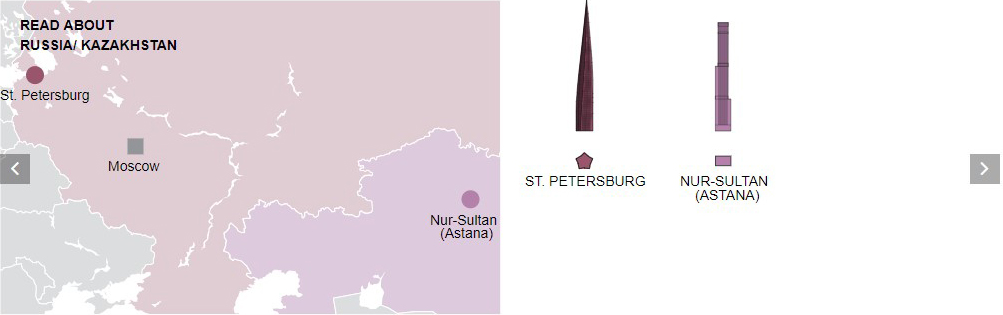

RUSSIA AND KAZAKHSTAN

During the last decade, two isolated supertalls have risen in Russia and Kazakhstan in connection with the powerful gas and oil industries in these countries.

In St. Petersburg, Russia, the partially state-owned multinational energy corporation Gazprom built the Lakhta Center to house its own headquarters, as well as a complex of other programs, including a medical center, performance hall, and planetarium.

In Nur-Sultan (formerly Astana), the capital city of Kazakhstan, the United Arab Emirates developer Aldar Properties built a complex called Abu Dhabi Plaza, including the first and only supertall in this Central Asian country, which enjoys vast oil, gas, and mineral resources.

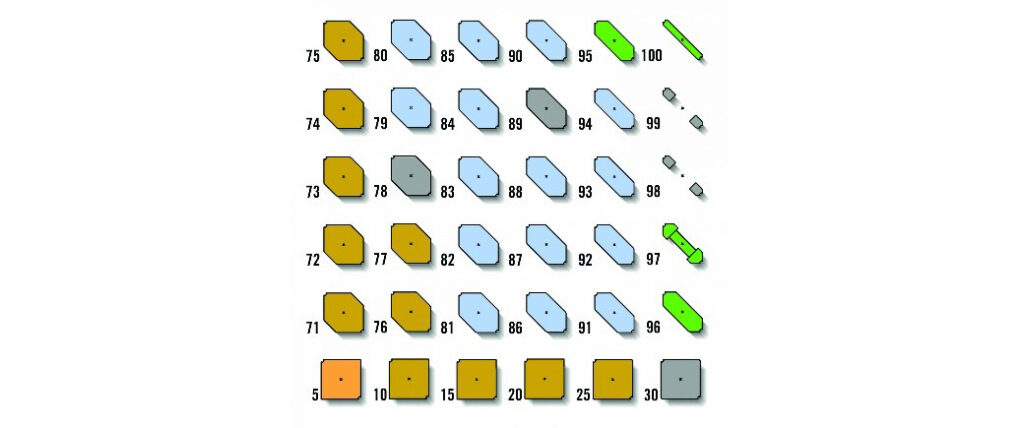

SUPERTALL GRID

The Supertall Grid is ordered by descending height, measured to the topmost architectural feature. Each row starts left to right. Hover on a building to see its name. Most of the towers are completed or topped

out: the others we assume will be completed by 2024. Using the filter menu, you can see all towers in a region highlighted. You can also reorder the projects chronologically to match the Lineup.

TYPOLOGY

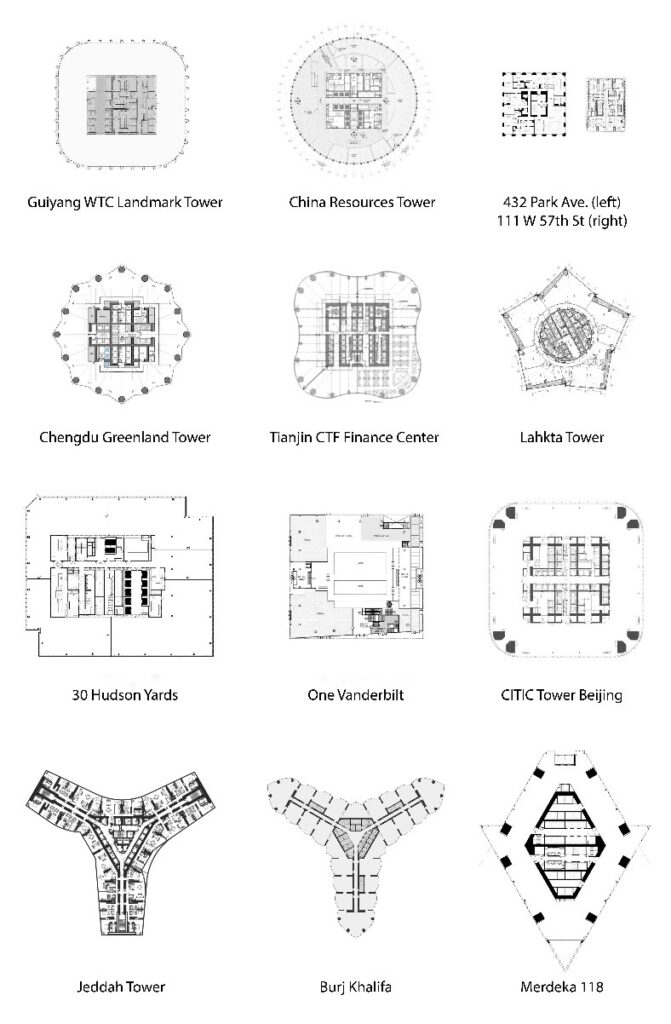

What determines the shape of a building? The architect’s creative idea is key, of course, but also the program – the space requirements and arrangement for the building’s uses. The needs of the program can be seen in the floor plan.

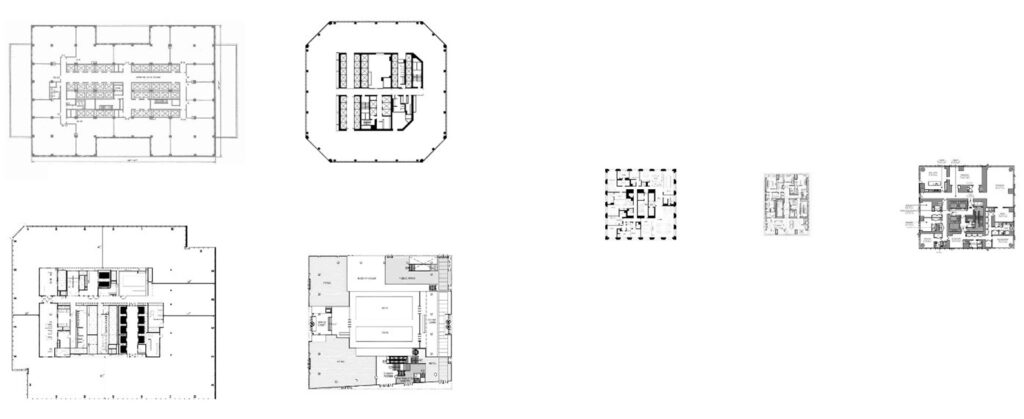

The floor plans here are all shown to the same scale. Some are big: they are the office building plans. Some are very tiny, just a quarter or less of the average office floors: they are luxury apartments.

The clearest way to tell the function of the building by its plan is to look at the core, the area at the center defined by thick walls that is packed with many small rooms, which are the elevators, staircases, bathrooms, and mechanical and service areas. How big is the core? What percent of the full floor plate does it occupy?

Top Row: Guiyang WTC Landmark Tower, China Resources Tower, 432 Park Avenue, 111 West 57th St. Second: Chengdu Greenland Tower, Tianjin CTF Finance Centre, Lakhta Center. Third: 30 Hudson Yards, One Vanderbilt, CITIC Tower. Last: Jeddah Tower, Burj Khalifa, Merdeka 118.

Office buildings have large cores principally because they must contain many elevators for vertical transit and machinery to serve large numbers of workers.

By contrast, an ultra-luxury apartment tower in Manhattan may have as few as two to five elevators serving a building of 80 or more stories. That tiny number is sufficient, though, to serve the limited traffic for only one or two apartments per floor.

Some residential structures do have a very large footprint – for example, the Burj Khalifa and Jeddah Tower. Their extraordinary height requires a wide footprint with three widely spaced wings to buttress the central core. At 828 meters, Burj is twice the height of New York’s 432 Park Avenue of 111 W. 57 Street.

No matter the dimensions of the floor plate, the area devoted to the core in supertalls is substantial because the internal space is needed to accommodate service areas and also because the stiff, heavy, reinforced concrete core is central to the stability of the structure.

Top Row: Guiyang WTC Landmark Tower, CITIC Tower. Bottom: Jeddah Tower, Burj Khalifa.

Plan shapes

The plans of the towers featured in the exhibition include squares, circles, stars, triangles/ diamonds, and Y-shaped, or slight variations of those forms. The spectrum of shapes suggests the variety and invention that can be found in recent supertall designs.

The plans also reveal a range of structural systems that can be applied to the challenge of exceptional height. The relation of the core and the columns is one place to observe different approaches. Many columns spaced closely together on the perimeter of the building indicates “tube” construction, as is used in China Resources Tower, Guiyang World Trade Center, and 432 Park Avenue – although those buildings look dramatically different in elevation.

Just a few large columns indicate a mega-column system –such as seen in the plan of CITIC Beijing. No columns at all, just walls, as in the plans for Burj Khalifa and Jeddah Tower, show a bearing-wall system. Structural systems are further examined in the ENGINEERING section of the menu.

The plans shown here represent typical floors, but in most cases, they show only a “slice” through the building that changes form dramatically above. In the twentieth century, most skyscrapers were constructed of steel, with columns and beams bolted in a grid, and postwar Modernism favored an aesthetics expression of the steel frame and “glass box.” Twenty-first-century towers explore a wide range of formal expression, while floor-to-ceiling curtain walls has become the near-universal façade treatment.

This formal invention has been made possible by computers and concrete. Designing and generating floor plans digitally, rather than by drawing each floor in pencil and reproducing as blueprints, eliminates the advantage of simple replication, story on story.

Computers allow for each floor plan to be different than the one above, so that sloping, twisting, and curving all become possible. Shifting shapes, especially tapering in the upper sections also accommodates a mixed-use program that places hotels – which require only a shallow ring of floor space – on the upper stories.

Building in concrete also allows for more “fluidity” of form and simplicity of construction since there is no fabrication of a jigsaw of numbered steel members off-site. Concrete is generally less expensive than steel.

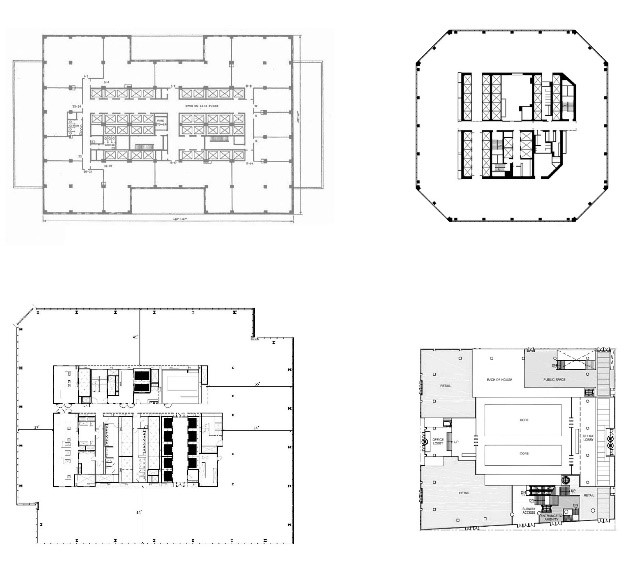

Floor plans of Shanghai World Financial Center by Kohn Pedersen Fox (KPF).

Mixed Use

The great majority of supertalls worldwide are mixed-use projects, generally combining offices on the lower floors and serviced apartments and/or a hotel on the upper zone. Public functions of restaurants, bars, or observation decks often occupy the top stories. Some of the sections shown here are color-coded to distinguish changes in program.

Office floors usually represent half or more of the lower stories where deep floor plates can accommodate large numbers of employees and office equipment. Middle zones may contain apartments, serviced by the hotel above. Since the design of hotel rooms value large windows and stunning views, smaller floor plates are desirable. Often the center of the tower is pierced by an open atrium – a dramatic void that can be experienced from the above and below, but also from the open-access corridor to the perimeter of hotel rooms. These shallow floor plates allow mixed-use supertalls to narrow towards the top either in setbacks or in a sculpted form that can give the tower a distinctive profile.

Supertalls almost always anchor a much larger development that includes multiple towers and retail structures, or even a district master plan, all under the coordinated control and strategy of a large real estate company that often represents government interests or investments. The economics of the towers, which are more expensive to build than several shorter towers with the same amount of space, rely on the prestige and added value the signature supertall gives to the larger project.

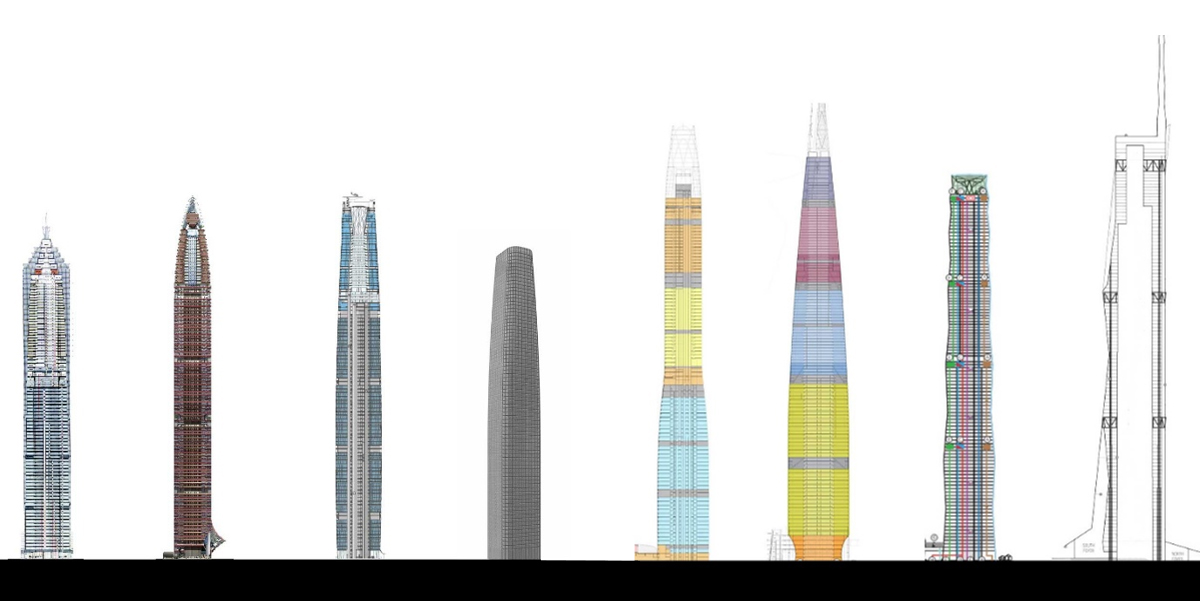

Top Row: Jin Mao, KK100, Guangzhou IFC, Giuyang WTC Landmark Tower. Bottom: Tianjin CTF Finance Centre, Lotte World Tower, Chengdu Greenland Tower, Merdeka 118

8 TOWERS

CITIES

Cities with multiple supertalls are rare, so their conditions and context seem to matter. In 2020, the cities with the greatest number of supertalls are New York with seven; Dubai with five; the Chinese cities of the Pearl River Delta, Shenzhen, with five, and Guangzhou with three; and both Shanghai and Wuhan with three. The Malaysian capital Kuala Lumpur also has three, counting the twin Petronas Towers as one project.

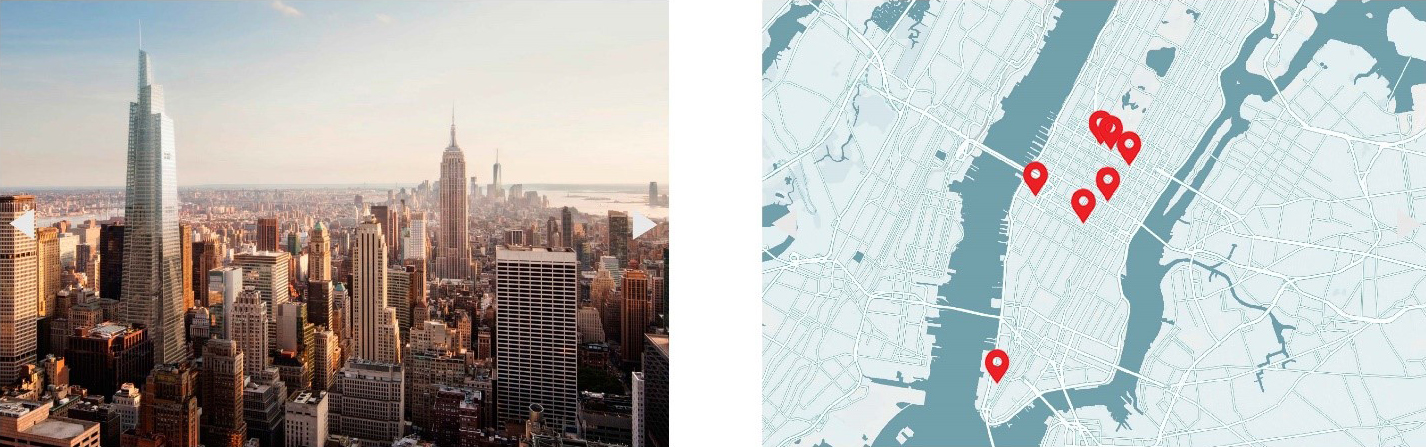

New York

New York, the city that invented the skyscraper in the 1870s and was home to the world’s tallest building for most of the twentieth century, today has the largest number of supertalls of any city in the world. Manhattan’s seven supertalls would have been nine if the twin towers of the original World Trade Center had not been destroyed by terrorist attacks on 9/11. But then, of course, downtown's only supertall at present, One World Trade Center, would not have risen at Ground Zero.

New York’s supertalls represent two types: office and residential. While there are many corporate headquarters in the city, the great majority of its skyscrapers have always been speculative real estate ventures. Indeed, the Empire State Building, our defining 20th-century supertall, was built without even an anchor tenant.

The first round of new construction after the devastating physical, economic, and psychological trauma of 9/11 was residential and began around 2009, but was stalled by the Great Recession. The three super-slender apartment towers 432 Park Avenue (2015), 111 W. 57 Street (2021) and Central Park Tower (2021) are the only ones of that new typology to surpass 380 meters. Since the completion of One World Trade Center (2014), Manhattan has also seen a resurgence of supertall office buildings in Midtown, with One Vanderbilt at Grand Central Terminal and others planned for Park Avenue, as well as the development of a new commercial and residential cluster in Far West Midtown, where at present 30 Hudson Yards (2019) is the only supertall.

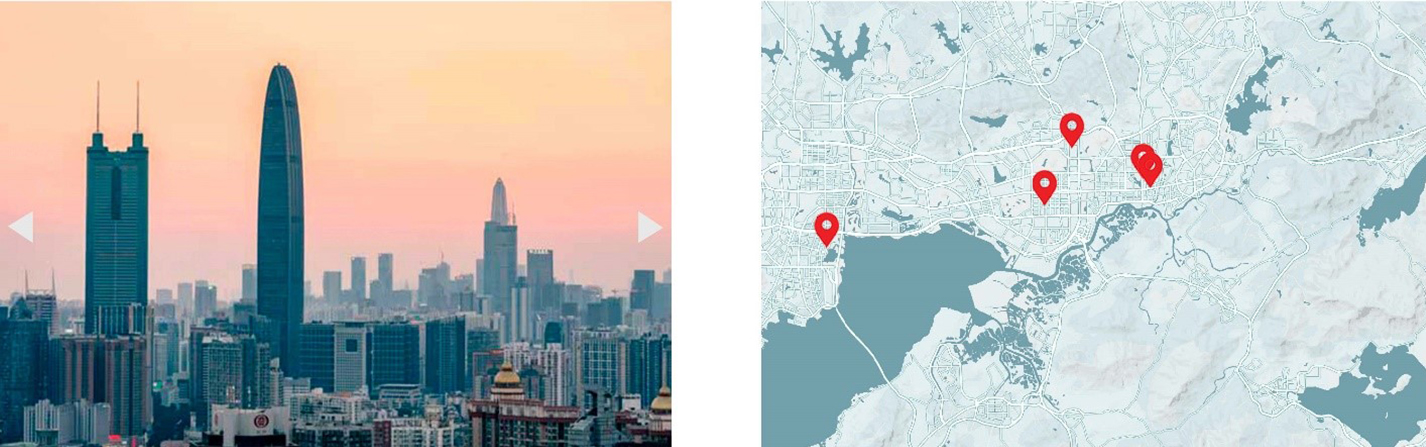

Shenzhen

Located in the Pearl River Delta, sharing a border with Hong Kong, Shenzhen became a city in 1979 and was established as China's first special economic zone in the 1980s. Less than four decades later, Shenzhen is a metropolis of 12.5 million inhabitants and has five supertalls, second only to New York in number. The earliest, Shun Hing Square (1996) is an office building, as are the 115-story Ping An Finance Center (2017), the headquarters of the giant insurance and banking company, and the China Resources Tower (2019), home to the state-owned conglomerate. KK100 (2011) and Shum Yip Upperhills (2020) are mixed-use towers that include hotels on the top floors. Shenzhen's rapid and sprawling growth created a polycentric development that spreads the supertalls out across the city, up to 10 miles apart.

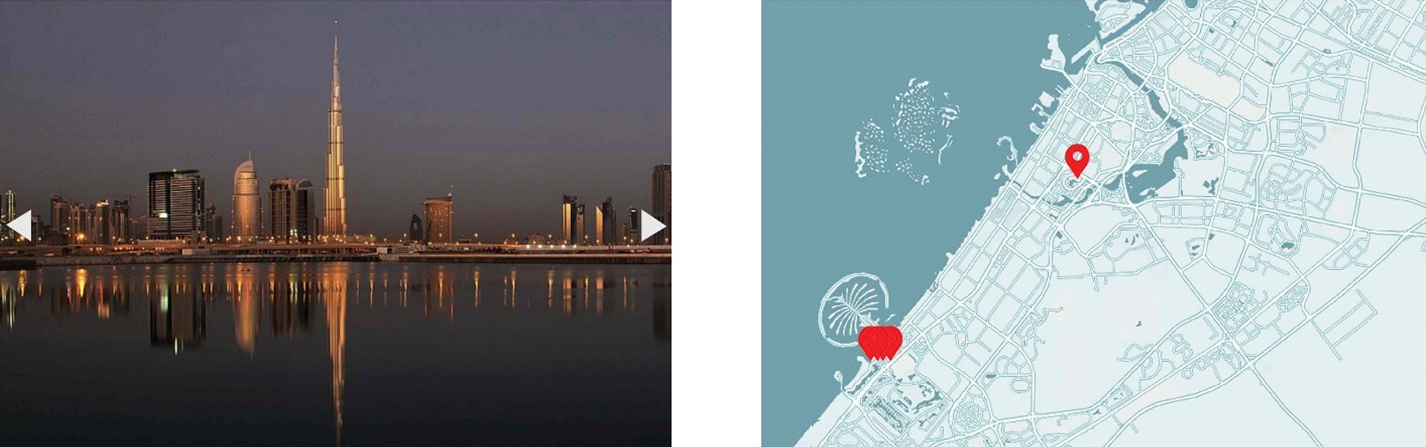

Dubai

In the 1990s, Dubai, a city-state of the United Arab Emirates with a population of only around 3 million, began to position itself as the financial, commercial, and recreation center for the Gulf region. Over-the-top real estate ventures such as the artificial Palm Islands and the world’s tallest building, Burj Khalifa (2010) drove the economy.

Many separate skyscraper developments were constructed at once, including the Manhattan-like skyline of Sheikh Zayed Road and the pencil-thin towers of Dubai Marina, where four supertalls crowded together on the so-called “tallest block in the world.” Including Burj Khalifa, all five towers are residential buildings or hotels.

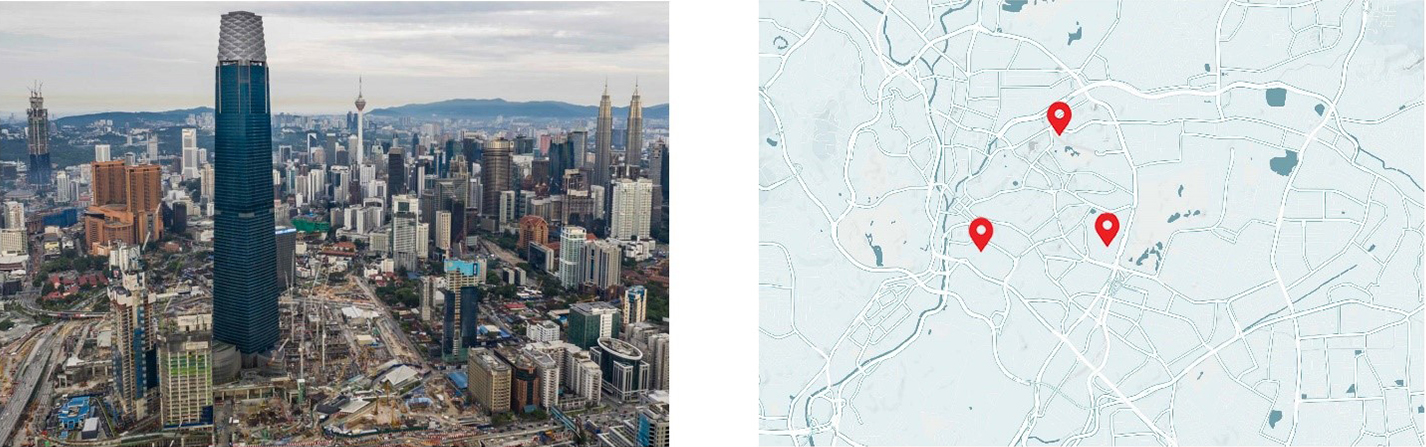

Kuala Lumpur

The skyline of Kuala Lumpur, the capital of Malaysia in Southeast Asia, belies its modest population of 1.8 million people. Like Dubai, the fast-growing city has embraced the supertall as both a symbol and a strategy of urban development, although its tallest towers are notably business, rather than residential buildings. In 1996, the twin Petronas Towers, developed by the government-owned oil and gas company Petronas, grabbed the title of world’s tallest building from the USA, passing the torch to a new continent. Designed by the Argentinian-American architect Cesar Pelli, the pair of towers, connected by a skybridge, project both modernity and cultural references in the stainless steel and glass forms that are based on an 8-point star, formed by intersecting squares, a reference to Islamic design and indigenous temple towers.

No major skyscraper would rise in the city for more than two decades, but today two new supertalls stand out only 1.5 miles from Petronas Towers, forming an almost equilateral triangle. Completed in 2019, Exchange 106 is the centerpiece of a government-sponsored new financial district and commercial complex. Now under construction, another complex on a site connected to national independence, Merdeka 118, developed by PNB Merdeka Ventures SDN Berhad, will be the city’s tallest building and at 644 m/ 2,113 ft. to the point of its spire and will surpass Shanghai Tower to become the second-tallest building in the world.

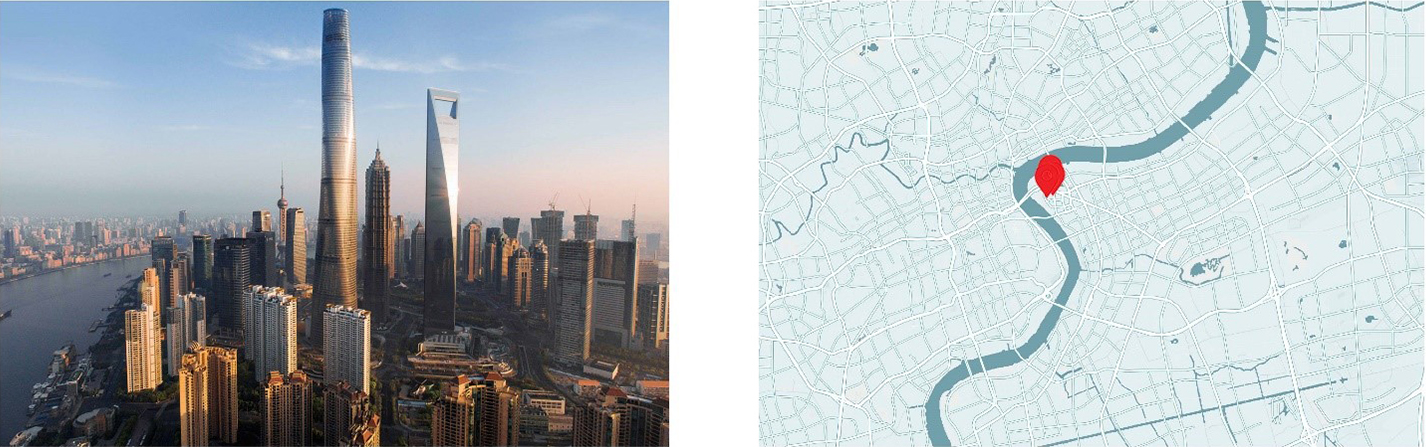

Shanghai

Shanghai today is a vast metropolis of some 27 million residents--the largest city in the world's most populous nation. Formerly a horizontal expanse of dense and sprawling low-rise neighborhoods, Shanghai has grown vertically in both the historic core of Puxi and in the new business district of Pudong on the east side of the Huangpu River. The master plan for the skyscraper district of Lujiazui Finance and Trade Zone, developed by the government from the mid-1990s, features the city's only three supertalls, clustered together but of very different designs: Jin Mao (1999), Shanghai World Financial Center (2008); and at 632 meters, Shanghai Tower (2015), the tallest building in the city and nation and the second-tallest in the world.

Wuhan

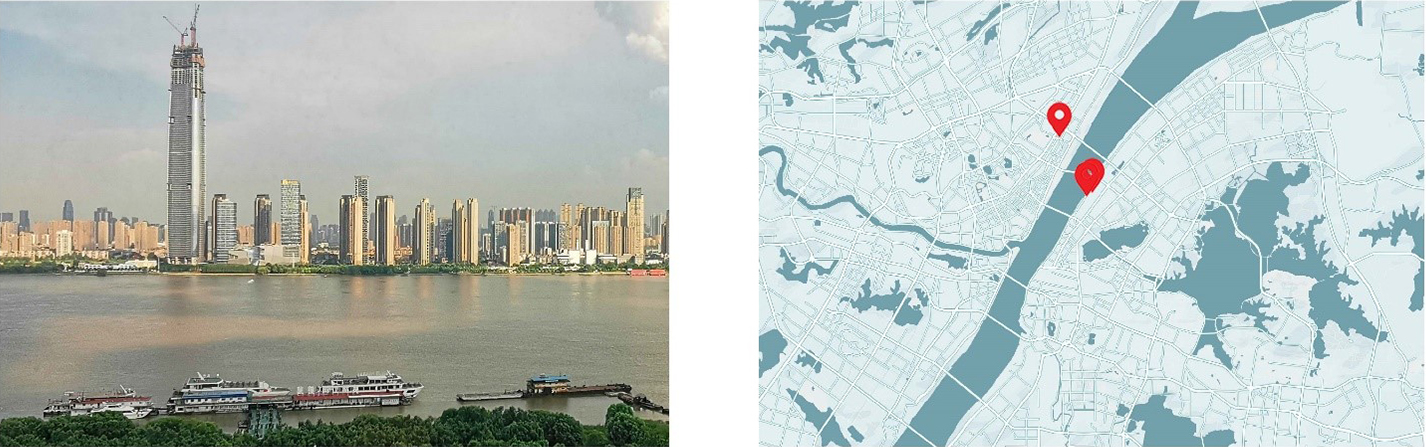

Wuhan is the capital city of the Hubei province in Central China. Composed of the historic towns of Wuchang, Hanyang, and Hankou, Wuhan consolidated in 1927 and today counts over 11 million people. Three supertalls have been planned and completed, or nearly completed, in Wuhan during the last decade: Wuhan Center Tower, Riverview Plaza A1, and Wuhan Greenland Center. Built on opposite sides of the Yangtze River but not too far apart, these mixed-use supertalls have been developed by state-owned or state-backed enterprises such as Wuhan CBD Investment Development Company, Shui On Land Limited, and Greenland Group. The tallest of these projects, Wuhan Greenland Center, by architects Adrian Smith and Gorden Gill, was originally designed to be 660 meters tall, but was capped at 1,560 ft (475 m) due to aviation regulations.

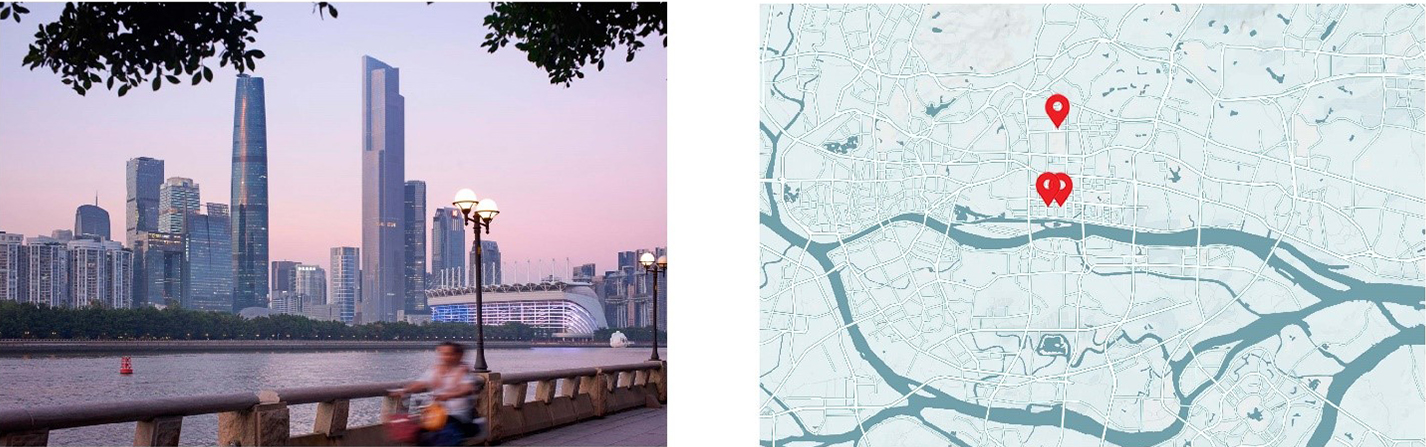

Guangzhou

Known in British colonial days as Canton, Guangzhou today is a Chinese city of 15 million people and the capital of the Guangdong Province, a major commercial and manufacturing region in the Pearl River Delta, the most-populous metropolitan area in mainland China. Like neighboring Shenzhen about 100 km to the south, Guangzhou has grown explosively in recent decades as the population, especially of factory workers, swelled through domestic migration from the western provinces.

Guangzhou built its first supertall in 1996, the office building CITIC Plaza, near the train station. The two others in our survey, Guangzhou IFC (2010) and CTF Finance Center (2016), also known as Chow Tai Fook or the East Tower, are a pair that mark the riverside end of a master-planned, central-city expansion, a massive swath of infrastructure and commercial development that connects to public transit below grade and to nearby buildings and below-grade retail, with a continuous park space above.

On the other side of the Pearl River, on axis with the mixed-use supertalls IFC and CTF, is a third structure known as Canton Tower, which topped out at 604 m/ 1,982 ft. in 2009. The innovative tower is principally used for TV and radio transmission and also serves as an observation deck and tourist destination that contains a vertical entertainment complex.

New York City supertalls.

NEW YORK CITY

New York City produced the first supertall, our benchmark Empire State Building, at the end of an unprecedented boom in high-rise office construction in the late 1920s that added more than a dozen towers of 40 to 50 or more stories to the skyline. The Empire State was not a typical tower of 600 to 800 feet: its 86th floor leveled off at 1,050 feet and the tip of its mooring-mast spire reached the altitude of 1,250 feet/ 381 meters. Not only was the Empire State 50 to 25 percent taller than its contemporaries, it was more than twice as big in its floor area – 2.1 million sq. ft. (as measured at the time: now 2.6 million), in contrast with the 900,000 sq. ft. of the Chrysler Building.

Floor area was as decisive a factor as height in the 1960s and ‘70s when each of the twin towers of the World Trade Center independently qualified as the world’s largest building (with a floor area of 4.5 million sq. ft.), as well as, briefly, the world’s two tallest buildings at 1,363 and 1,368 feet. The Sixties was a period of gigantism in the scale of its towers that was not matched until the Chinese supertalls Ping An (2017) and CITIC, Beijing (2018).

New York developers erected many new skyscrapers in the later 20th century, but no supertalls. This was largely because the 1961 zoning laws restricted the maximum size of towers by a Floor Area Ratio (FAR), a formula geared to the area of the lot and the type of “use” district. Thus, to erect an office building that was taller than around 800 feet and 55 stories required a very large site – rare in Manhattan – and special allowances for bonus FAR or transferred development rights. When the World Trade Center was destroyed on 9/11/2001, the Empire State once again became the tallest building in the city.

In the aftermath of the terrorist attacks, many predicted the end of skyscrapers, opining that people would be too nervous to live or work in tall towers and that lenders would decline to finance them. Those predictions were short-lived, especially in other parts of the world, but soon also in New York. Today, less than two decades after 9/11, there are six new towers taller than the Empire State Building on the Manhattan skyline – the largest number of supertalls of any city in the world.

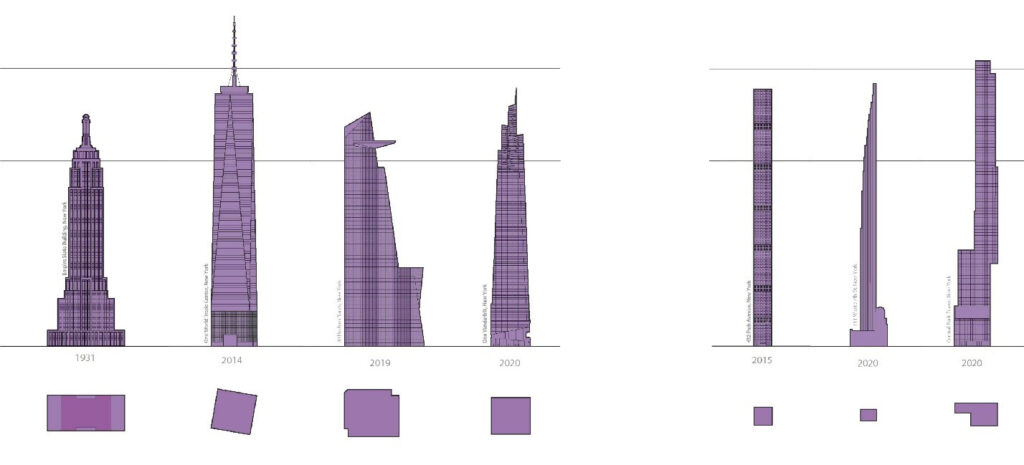

Left: New York City office supertalls. From left to right: Empire State Building, One World Trade Center, 30 Hudson Yards, and One Vanderbilt. Right: New York City residential supertalls. From left to right: 432 Park Avenue, 111 West 57th St, and Central Park Tower.

Since the completion of One World Trade Center at the Ground Zero site in 2014, Manhattan has seen a resurgence of supertall office buildings in Midtown, with One Vanderbilt, topped out in 2019, and 30 Hudson Yards (2019) in Far West Midtown. Others are planned for the district that was up-zoned by the City in 2017 to allow more FAR in a 73-block area called East Midtown that surrounds Grand Central Terminal and extends north in broad swath centered on Park Avenue to 57th Street. This includes the new headquarters for JP Morgan Chase to be erected on the site of the classic postwar glass box at 270 Park Avenue, designed for Union Carbide by SOM in 1957, under demolition in 2020.

The first round of new construction – which began around 2008, but was stalled by the Great Recession – was residential. Developers, architects, and engineers invented a new typology: the super-slender, ultra-luxury, condominium tower. These thin reeds use air rights purchased from under-developed neighbors to add extra stories to small lots at high-value locations, such as the southern edge of Central Park and West 57th Street, which acquired the moniker Billionaire’s Row. With a slenderness ratio of at least 10:1 – and in the case of 111 W. 57th Street, an astonishing 23:1 – these buildings represent a true innovation in skyscraper history.

Left top row: Empire State; One WTC. Bottom: 30 Hudson Yards; One Vanderbilt. Right: 432 Park Avenue, 111 West 57th St, Central Park Tower

As can be seen in the relation of elevation silhouettes and the typical floor plans above, all to the same scale, the office towers have large footprints at street level and spacious upper floors arranged around a robust central core built of thick walls of reinforced concrete. The only building with a different plan and structural system is the 1931 Empire State, which uses its twentieth-century steel-skeleton construction in a uniform grid of columns that intrude on the open space of the interior. The multiplicity of elevator banks rise within the steel frame. In the twenty-first century towers, the office floors are open plan, providing as much uninterrupted space, and views, as possible.

The development strategy of these super-slender towers is to squeeze as much of the valuable, purchased FAR into a very small footprint and to raise each floor of apartments (usually only one, or perhaps two, apartments per floor) as high in the sky as possible to capture spectacular views. Because of the small number of units overall, the elevators can be reduced to two to five shafts – unlike an office building that requires many banks for efficient vertical transit – thus also keeping the ratio of saleable floor area to the mechanical core highly profitable for the developer. This strategy is fully explained in the Museum’s 2013 exhibition SKY HIGH & the Logic of Luxury.

One World Trade Center, city view. Richard Berenholtz.

One Vanderbilt, city view with the Empire State Building and One World Trade Center in the background. KPF.

One Vanderbilt, city view with the Empire State Building and One World Trade Center in the background. KPF.

30 Hudson Yards, city view. KPF.

Residential supertalls south of Central Park. Andrew Nelson and José Hernández.