Concrete – liquid stone – is both unique and ubiquitous in our modern world. It is the substance most widely used by humans after water. It has many desirable qualities for buildings – strength, fire-resistance, and malleability – but also has a high “carbon cost” of embodied energy that contributes to climate change. The 70 years of the history of the skyscraper, from the 1880s, was a story of steel. Today, though, almost all skyscrapers are built of concrete. That story has had no clear narrative: finding that thread is the subject of this exhibition.

Reinforced concrete was rarely used as a primary structural system for skyscrapers in the first half of the 20th century, but it was present in every tall building in foundations and many hidden areas. The few all-concrete high-rises were experiments and one-offs. Beyond North America, though, reinforced concrete was often the most familiar and economical material of construction.

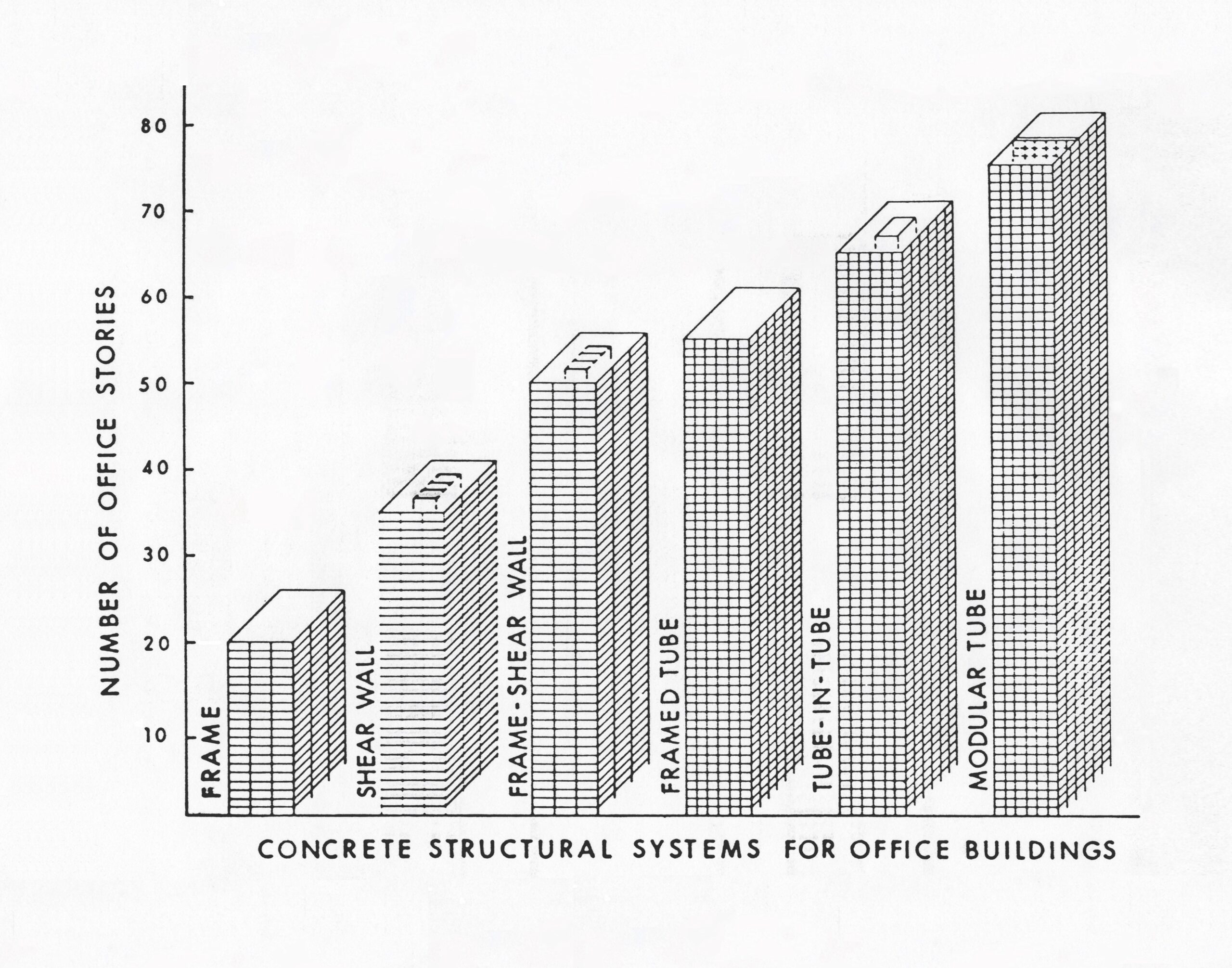

In the 1960s, concrete became an arena of innovation in the research and practice of architects, engineers, material suppliers, and builders. They invented new systems of structural design: “tubes,” which carried loads on exterior walls, and massive concrete cores that sped construction and stiffened perimeter enclosure systems. Along with greater material strengths, these approaches allowed towers to grow ever taller, climbing to new heights through the 1990s at the same time that the geography of supertalls spread to Asia and the Middle East.

Concrete offers unlimited opportunities for formal invention: poured into molds, it can take any shape, creating sculptural forms of thin ribs, thick walls, or screens. But economics also underpins the logic of all commercial architecture, and concrete makes sense for many reasons. The race to the skies today has been won by concrete.

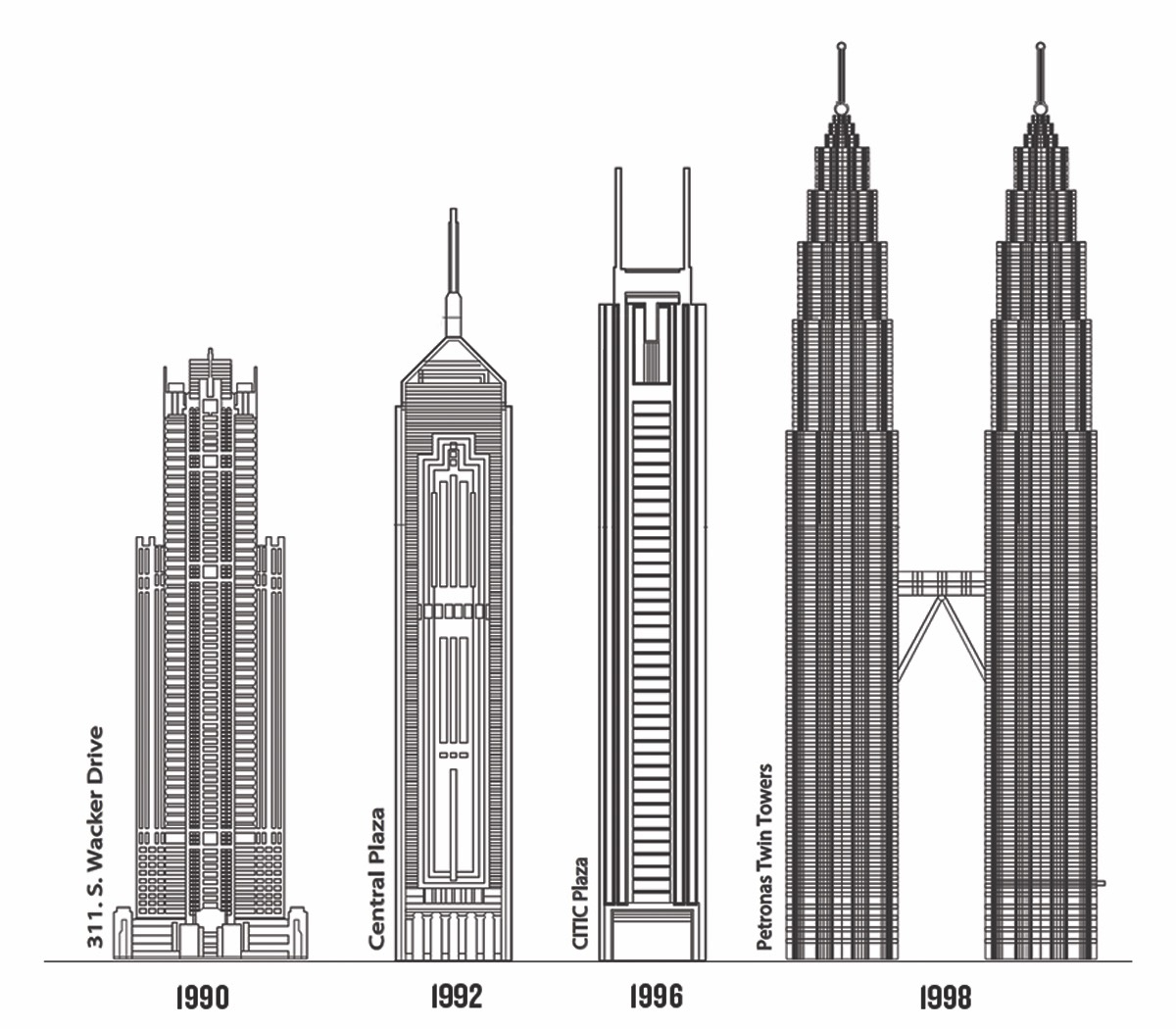

TALLEST CONCRETE SKYSCRAPERS by year of completion

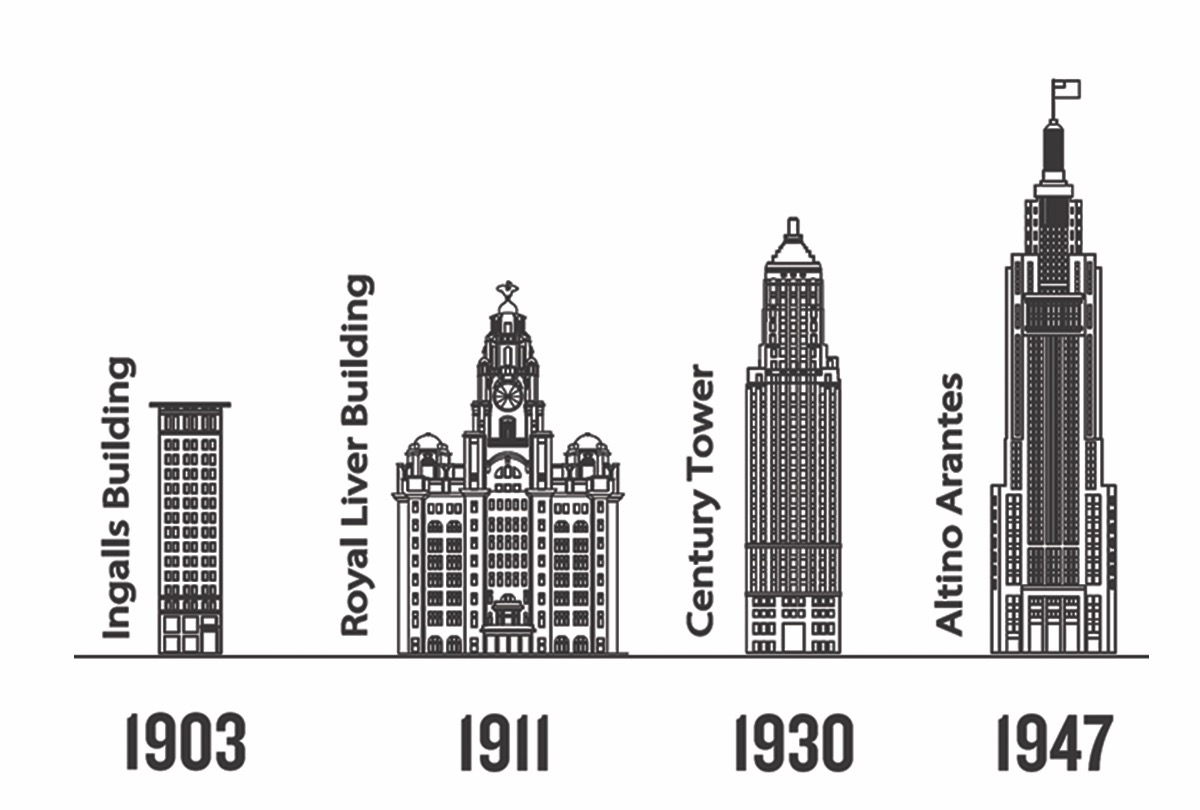

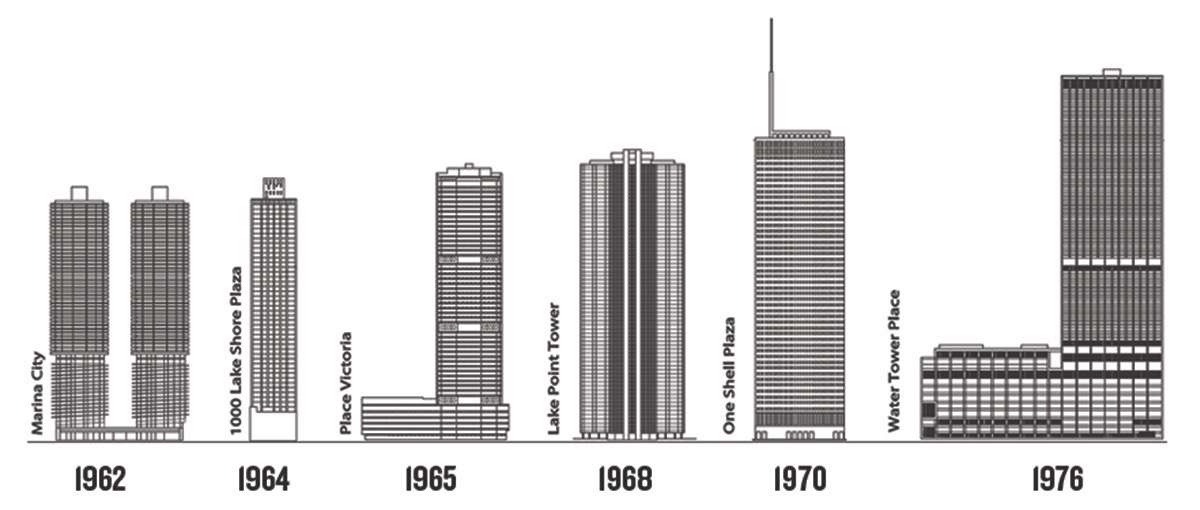

In our research for the exhibition, one of the first things the Museum did to try to understand the rise of the concrete skyscraper was to make a “World’s Tallest” graphic of all the buildings that, in succession, took the title of the tallest building constructed of reinforced concrete. We know of no other graphic that pursues this concept or includes all of these buildings. We also knew the concrete lineup would look very different from a “World’s Tallest” chart that includes buildings of steel, the material that dominated high-rise construction through the mid-1970s.

Our chart illustrates the astonishing ascent over more than twelve decades, and reveals significant moments of innovation and its impact. It shows the rise of the reinforced-concrete skyscraper from the first clear example in 1903, the Ingalls Building in Cincinnati, to the record holder today, the Burj Khalifa in Dubai, which is 13 times taller. Progress was not steady: there were few examples in the first half of the 20th century, but after WWII construction boomed and average heights rose. The next step to towers of 1,000 ft./ 300 meters and taller came in the 1990s, when supertalls also began their global spread. Then a giant leap in this century when the Burj Khalifa nearly doubled the height of the Petronas Towers.

The buildings and the dates in the lineup make visible three eras of innovation and widespread adoption in the use of concrete from the 1950s to today. As the exhibition documents, these eras were made possible by progress in engineering knowledge and advances in material strengths and construction techniques.

Innovation in concrete design and construction boomed in the 1960s when, especially in Chicago, both residential and office towers stacked 50 to 70 stories in flat-topped Modernist towers. Gradual and incremental improvements in concrete mixes, efficient building techniques, and engineering concepts such as flat-plate construction, tube structures, and composite concrete-and-steel design allowed greater economies and heights.

Further advances through the 1980s in high-strength mixes, new methods of computer-aided structural analysis, and better pumps enabled concrete to achieve greater heights. In 1990, 311 S. Wacker in Chicago set a new record, but was the last "tallest" in North America's dominance. Thereafter, the title moved to Asia and the Middle East.

The invention and evolution of the skyscraper as a building type is principally an American story, but the history of the concrete skyscraper is international. Of the 16 buildings that have held the title of "world's tallest concrete skyscraper," eight are in the U.S. (six in Chicago); one in South America; two in Canada; one in Europe: three in Asia: and one, the Burj Khalifa, in the Middle East. Viewing the skyscraper through a material lens offers another way to understand its complicated history.

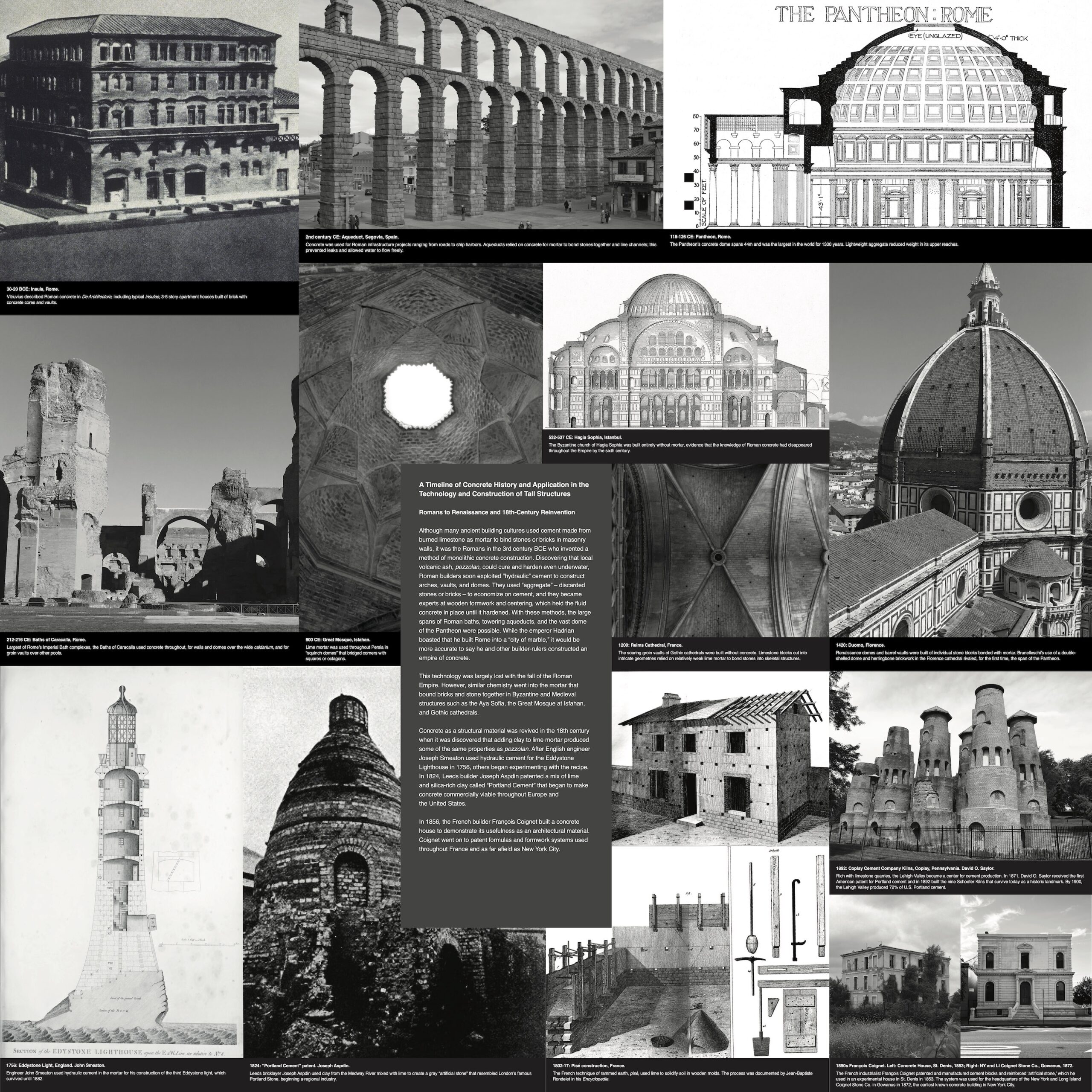

A Timeline of Concrete History and Application in the Technology and Construction of Tall Structures

The exhibition begins with a 30-foot long timeline, organized in eight panels that present significant chapters or periods in the evolution of the concrete skyscraper. After a prologue on Roman concrete and the rediscovery and early industrial production of Portland Cement, the focus is on the late-19th century development of reinforced concrete. The patent era, beginning in the 1890s, spawned many competing systems of using metal rebar embedded in concrete to make it stronger. Entrepreneur engineers and builders applied their systems mostly to factory architecture and stretched them to as tall as 16 stories by the 1910s.

The remaining panels focus on the development of true skyscrapers as a building type. The chronology groups buildings in eras that are marked by new forms, architectural and engineering innovations, and material advances. They illustrate the rise of the concrete skyscraper over more than a century – both as the ascent in height and, also, the expanding dominance of the material in the structure and construction of tall buildings worldwide.

Romans to Renaissance and 18th-Century Reinvention

Although many ancient building cultures used cement made from burned limestone as mortar to bind stones or bricks in masonry walls, it was the Romans in the 3rd century BCE who invented a method of monolithic concrete construction. Discovering that a local volcanic ash, pozzolan, could cure and harden even underwater, Roman builders soon exploited “hydraulic” cement to construct arches, vaults, and domes. They used “aggregate” – discarded stones or bricks – to economize on cement, and they became experts at wooden formwork and centering, which held the fluid concrete in place until it hardened. With these methods, the large spans of Roman baths, towering aqueducts, and the vast dome of the Pantheon were possible. While the emperor Hadrian boasted that he built Rome into a “city of marble,” it would be more accurate to say he and other builder-rulers constructed an empire of concrete.

This technology was largely lost with the fall of the Roman Empire. However, similar chemistry went into the mortar that bound bricks and stone together in Byzantine and Medieval structures such as the Aya Sofia, the Great Mosque at Isfahan, and Gothic cathedrals.

Concrete as a structural material was revived in the 18th century when it was discovered that adding clay to lime mortar produced some of the same properties as pozzolan. After English engineer Joseph Smeaton used hydraulic cement for the Eddystone Lighthouse in 1756, others began experimenting with the recipe. In 1824, Leeds builder Joseph Aspdin patented a mix of lime and silica-rich clay called “Portland Cement” that began to make concrete commercially viable throughout Europe and the United States.

In 1856, the French builder François Coignet built a concrete house to demonstrate its usefulness as an architectural material. Coignet went on to patent formulas and formwork systems used throughout France and as far afield as New York City.

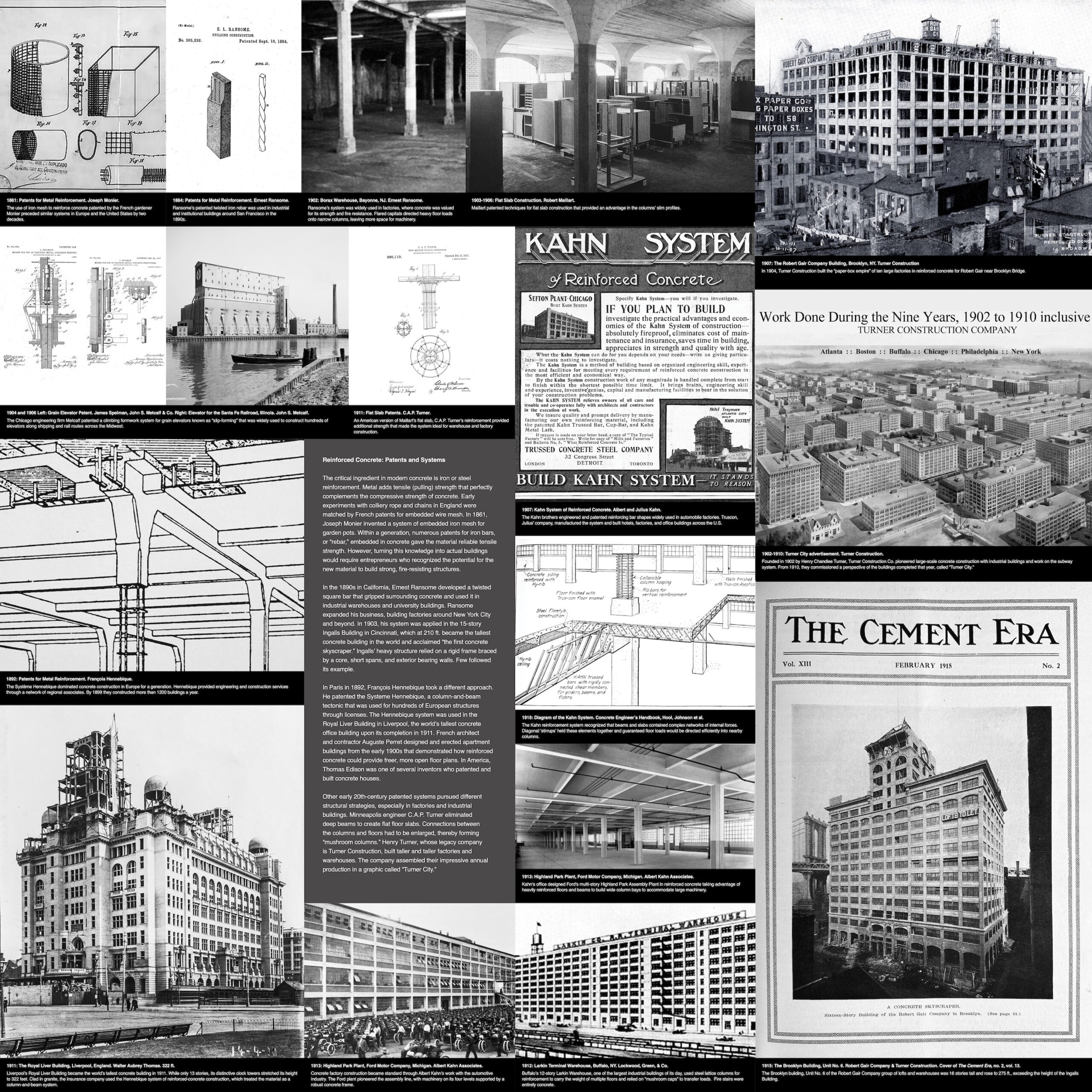

Reinforced Concrete: Patents and Systems

The critical ingredient in modern concrete is iron or steel reinforcement. Metal adds tensile (pulling) strength that perfectly complements the compressive strength of concrete. Early experiments with colliery rope and chains in England were matched by French patents for embedded wire mesh. In 1861, Joseph Monier invented a system of embedded iron mesh for garden pots. Within a generation, numerous patents for iron bars, or “rebar,” embedded in concrete gave the material reliable tensile strength. However, turning this knowledge into actual buildings would require entrepreneurs who recognized the potential for the new material to build strong, fire-resisting structures.

In the 1890s in California, Ernest Ransome developed a twisted square bar that gripped surrounding concrete and used it in industrial warehouses and university buildings. Ransome expanded his business, building factories around New York City and beyond. In 1903, his system was applied in the 15-story Ingalls Building in Cincinnati, which at 210 ft. became the tallest concrete building in the world and acclaimed “the first concrete skyscraper.” Ingalls’ heavy structure relied on a rigid frame braced by a core, short spans, and exterior bearing walls. Few followed its example.

In Paris in 1892, François Hennebique took a different approach. He patented the Systeme Hennebique, a column-and-beam tectonic that was used for hundreds of European structures through licenses. The Hennebique system was used in the Royal Liver Building in Liverpool, the world’s tallest concrete office building upon its completion in 1911. French architect and contractor Auguste Perret designed and erected apartment buildings from the early 1900s that demonstrated how reinforced concrete could provide freer, more open floor plans. In America, Thomas Edison was one of several inventors who patented and built concrete houses.

Other early 20th-century patented systems pursued different structural strategies, especially in factories and industrial buildings. Minneapolis engineer C.A.P. Turner eliminated deep beams to create flat floor slabs. Connections between the columns and floors had to be enlarged, thereby forming “mushroom columns.” Henry Turner, whose legacy company is Turner Construction, built taller and taller factories and warehouses. The company assembled their impressive annual production in a graphic called “Turner City.”

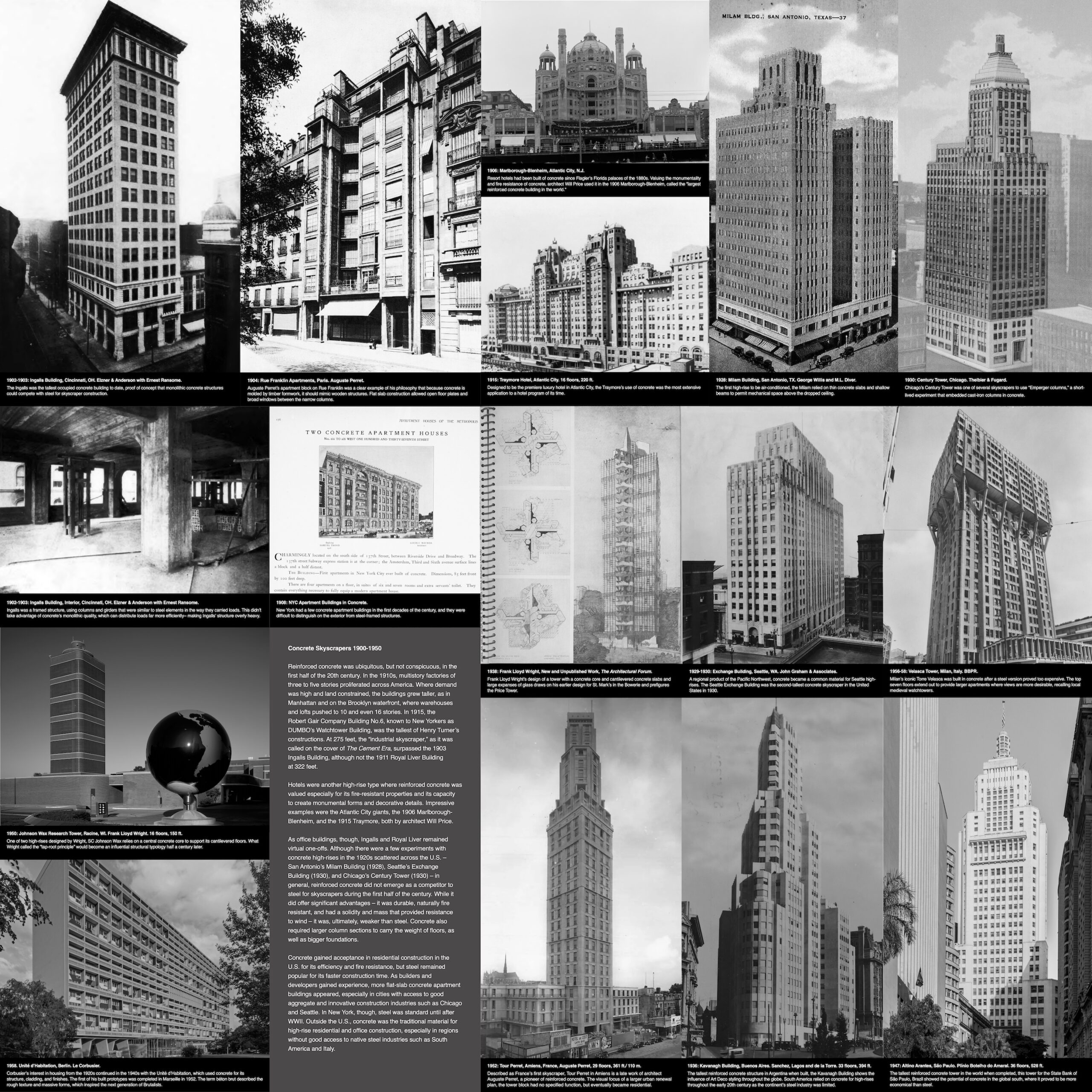

Concrete Skyscrapers 1900-1950

Reinforced concrete was ubiquitous, but not conspicuous, in the first half of the 20th century. In the 1910s, multistory factories of three to five stories proliferated across America. Where demand was high and land constrained, the buildings grew taller, as in Manhattan and on the Brooklyn waterfront, where warehouses and lofts pushed to 10 and even 16 stories. In 1915, the Robert Gair Company Building No.6, known to New Yorkers as DUMBO’s Watchtower Building, was the tallest of Henry Turner’s constructions. At 275 feet, the “industrial skyscraper,” as it was called on the cover of The Cement Era, surpassed the 1903 Ingalls Building, although not the 1911 Royal Liver Building at 322 feet.

Hotels were another high-rise type where reinforced concrete was valued especially for its fire-resistant properties and its capacity to create monumental forms and decorative details. Impressive examples were the Atlantic City giants, the 1906 Marlborough-Blenheim, and the 1915 Traymore, both by architect Will Price.

As office buildings, though, Ingalls and Royal Liver remained virtual one-offs. Although there were a few experiments with concrete high-rises in the 1920s scattered across the U.S. – San Antonio’s Milam Building (1928), Seattle’s Exchange Building (1930), and Chicago’s Century Tower (1930) – in general, reinforced concrete did not emerge as a competitor to steel for skyscrapers during the first half of the century. While it did offer significant advantages – it was durable, naturally fire resistant, and had a solidity and mass that provided resistance to wind – it was, ultimately, weaker than steel. Concrete also required larger column sections to carry the weight of floors, as well as bigger foundations.

Concrete gained acceptance in residential construction in the U.S. for its efficiency and fire resistance, but steel remained popular for its faster construction time. As builders and developers gained experience, more flat-slab concrete apartment buildings appeared, especially in cities with access to good aggregate and innovative construction industries such as Chicago and Seattle. In New York, though, steel was standard until after WWII. Outside the U.S., concrete was the traditional material for high-rise residential and office construction, especially in regions without good access to native steel industries such as South America and Italy.

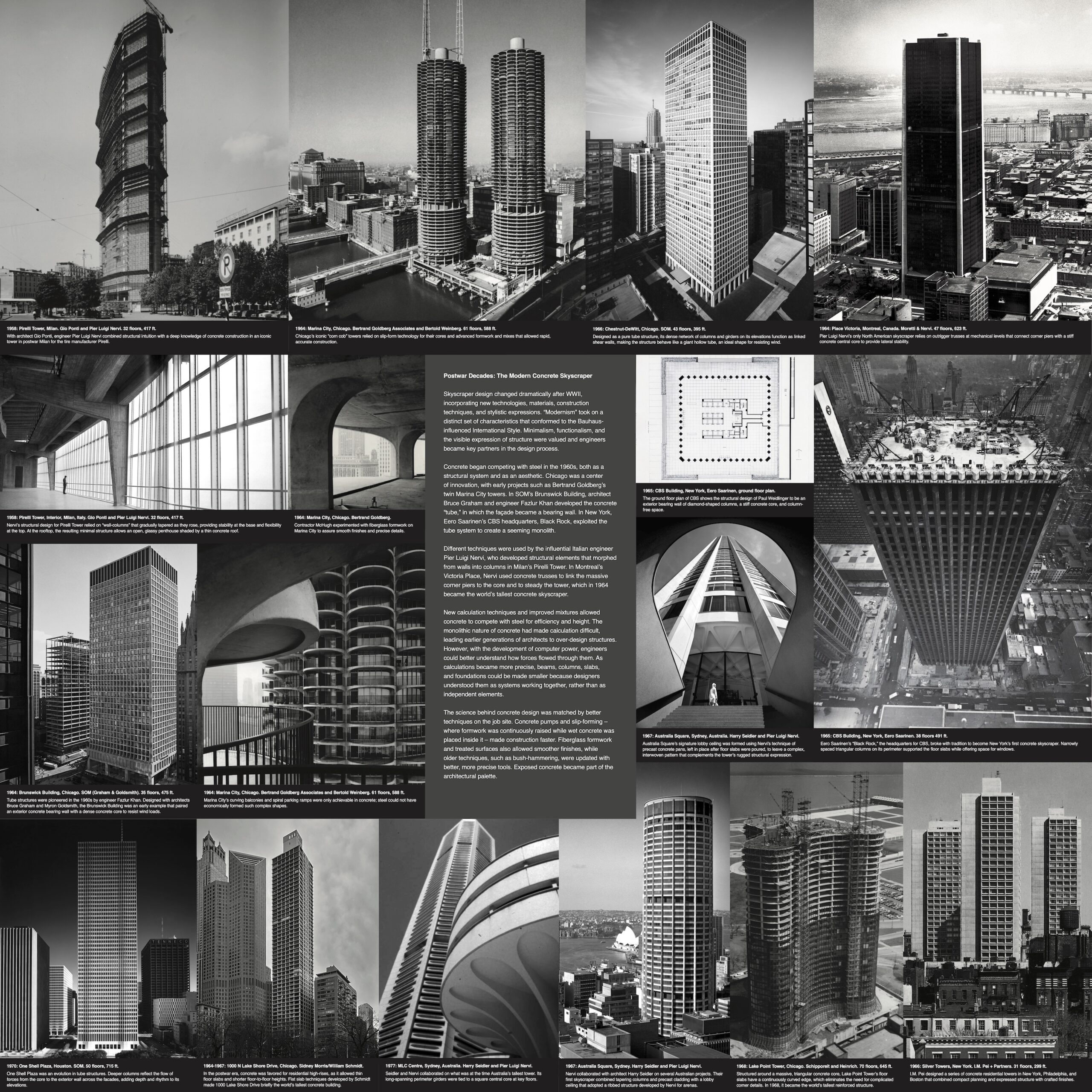

Postwar Decades: The Modern Concrete Skyscraper

Skyscraper design changed dramatically after WWII, incorporating new technologies, materials, construction techniques, and stylistic expressions. “Modernism” took on a distinct set of characteristics that conformed to the Bauhaus-influenced International Style. Minimalism, functionalism, and the visible expression of structure were valued and engineers became key partners in the design process.

Concrete began competing with steel in the 1960s, both as a structural system and as an aesthetic. Chicago was a center of innovation, with early projects such as Bertrand Goldberg’s twin Marina City towers. In SOM’s Brunswick Building, architect Bruce Graham and engineer Fazlur Khan developed the concrete “tube,” in which the façade became a bearing wall. In New York, Eero Saarinen’s CBS headquarters, Black Rock, exploited the tube system to create a seeming monolith.

Different techniques were used by the influential Italian engineer Pier Luigi Nervi, who developed structural elements that morphed from walls into columns in Milan’s Pirelli Tower. In Montreal’s Victoria Place, Nervi used concrete trusses to link the massive corner piers to the core and to steady the tower, which in 1964 became the world’s tallest concrete skyscraper.

New calculation techniques and improved mixtures allowed concrete to compete with steel for efficiency and height. The monolithic nature of concrete had made calculation difficult, leading earlier generations of architects to over-design structures. However, with the development of computer power, engineers could better understand how forces flowed through them. As calculations became more precise, beams, columns, slabs, and foundations could be made smaller because designers understood them as systems working together, rather than as independent elements.

The science behind concrete design was matched by better techniques on the job site. Concrete pumps and slip-forming – where formwork was continuously raised while wet concrete was placed inside it – made construction faster. Fiberglass formwork and treated surfaces also allowed smoother finishes, while older techniques, such as bush-hammering, were updated with better, more precise tools. Exposed concrete became part of the architectural palette.

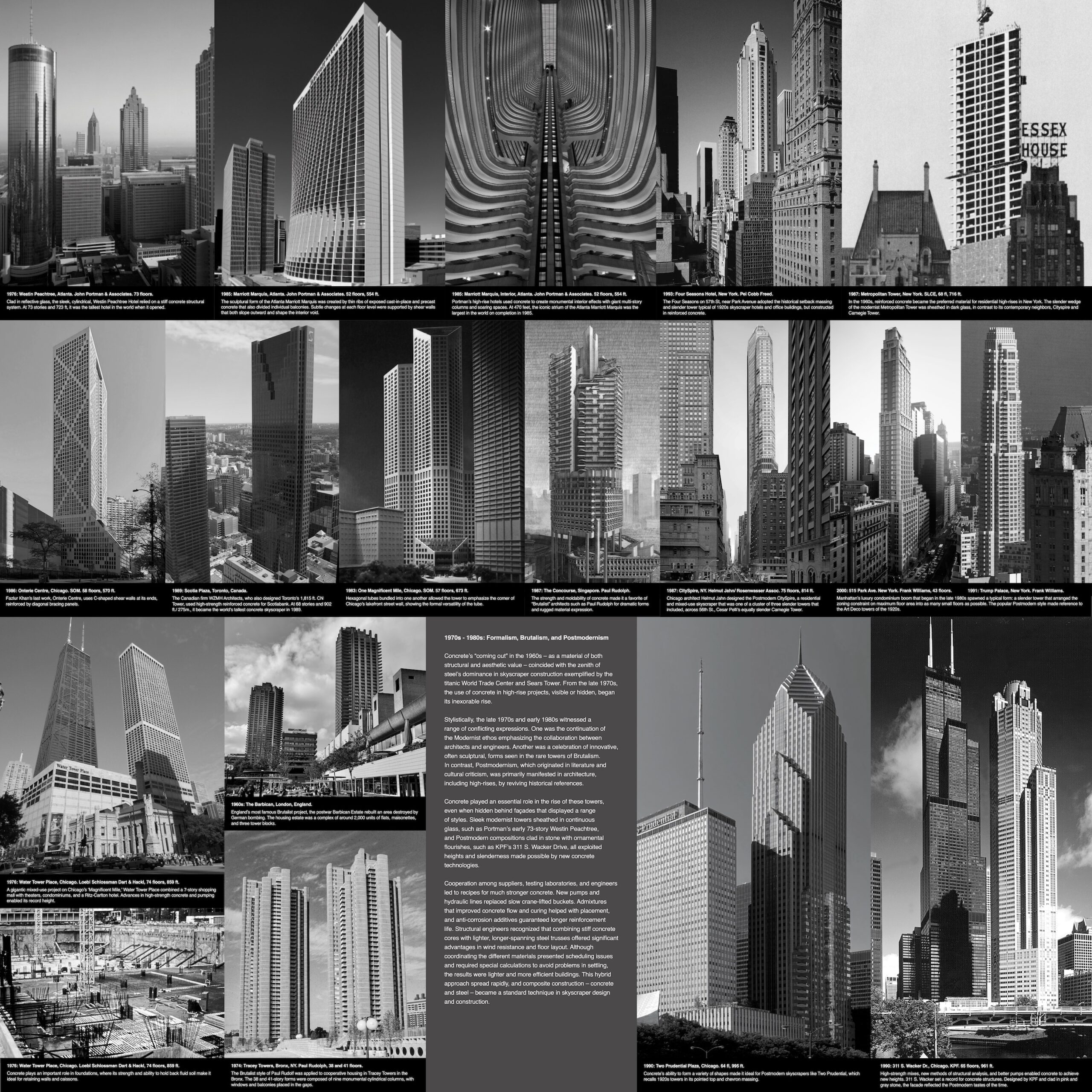

1970s - 1980s: Formalism, Brutalism, and Postmodernism

Concrete’s “coming out” in the 1960s – as a material of both structural and aesthetic value – coincided with the zenith of steel’s dominance in skyscraper construction exemplified by the titanic World Trade Center and Sears Tower. From the late 1970s, the use of concrete in high-rise projects, visible or hidden, began its inexorable rise.

Stylistically, the late 1970s and early 1980s witnessed a range of conflicting expressions. One was the continuation of the Modernist ethos emphasizing the collaboration between architects and engineers. Another was a celebration of innovative, often sculptural, forms seen in the rare towers of Brutalism. In contrast, Postmodernism, which originated in literature and cultural criticism, was primarily manifested in architecture, including high-rises, by reviving historical references.

Concrete played an essential role in the rise of these towers, even when hidden behind façades that displayed a range of styles. Sleek modernist towers sheathed in continuous glass, such as Portman’s early 73-story Westin Peachtree, and Postmodern compositions clad in stone with ornamental flourishes, such as KPF’s 311 S. Wacker Drive, all exploited heights and slenderness made possible by new concrete technologies.

Cooperation among suppliers, testing laboratories, and engineers led to recipes for much stronger concrete. New pumps and hydraulic lines replaced slow crane-lifted buckets. Admixtures that improved concrete flow and curing helped with placement, and anti-corrosion additives guaranteed longer reinforcement life. Structural engineers recognized that combining stiff concrete cores with lighter, longer-spanning steel trusses offered significant advantages in wind resistance and floor layout. Although coordinating the different materials presented scheduling issues and required special calculations to avoid problems in settling, the results were lighter and more efficient buildings. This hybrid approach spread rapidly, and composite construction – concrete and steel – became a standard technique in skyscraper design and construction.

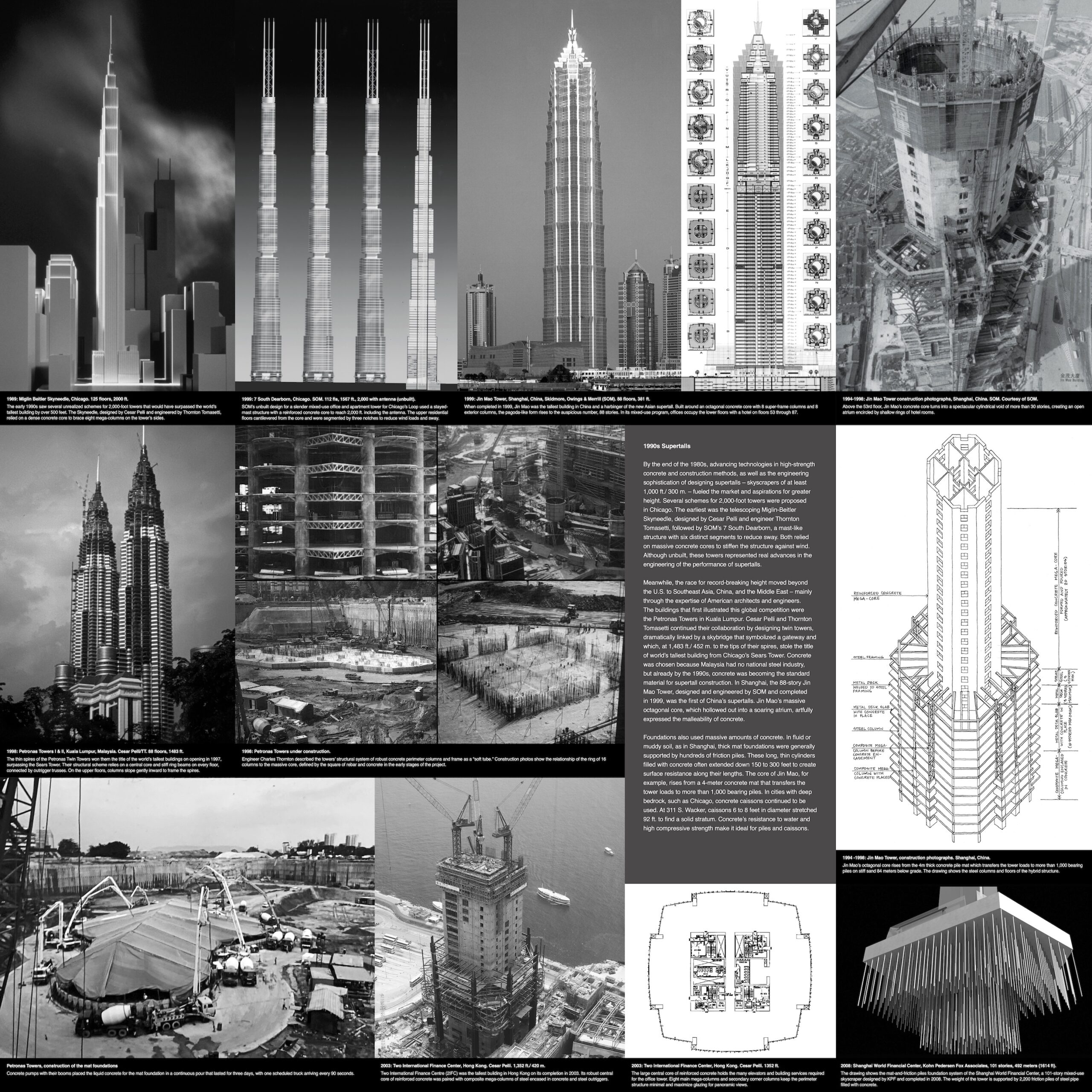

1990s Supertalls

By the end of the 1980s, advancing technologies in high-strength concrete and construction methods, as well as the engineering sophistication of designing supertalls – skyscrapers of at least 1,000 ft./ 300 m. – fueled the market and aspirations for greater height. Several schemes for 2,000-foot towers were proposed in Chicago. The earliest was the telescoping Miglin-Beitler Skyneedle, designed by Cesar Pelli and engineer Thornton Tomasetti, followed by SOM’s 7 South Dearborn, a mast-like structure with six distinct segments to reduce sway. Both relied on massive concrete cores to stiffen the structure against wind. Although unbuilt, these towers represented real advances in the engineering of the performance of supertalls.

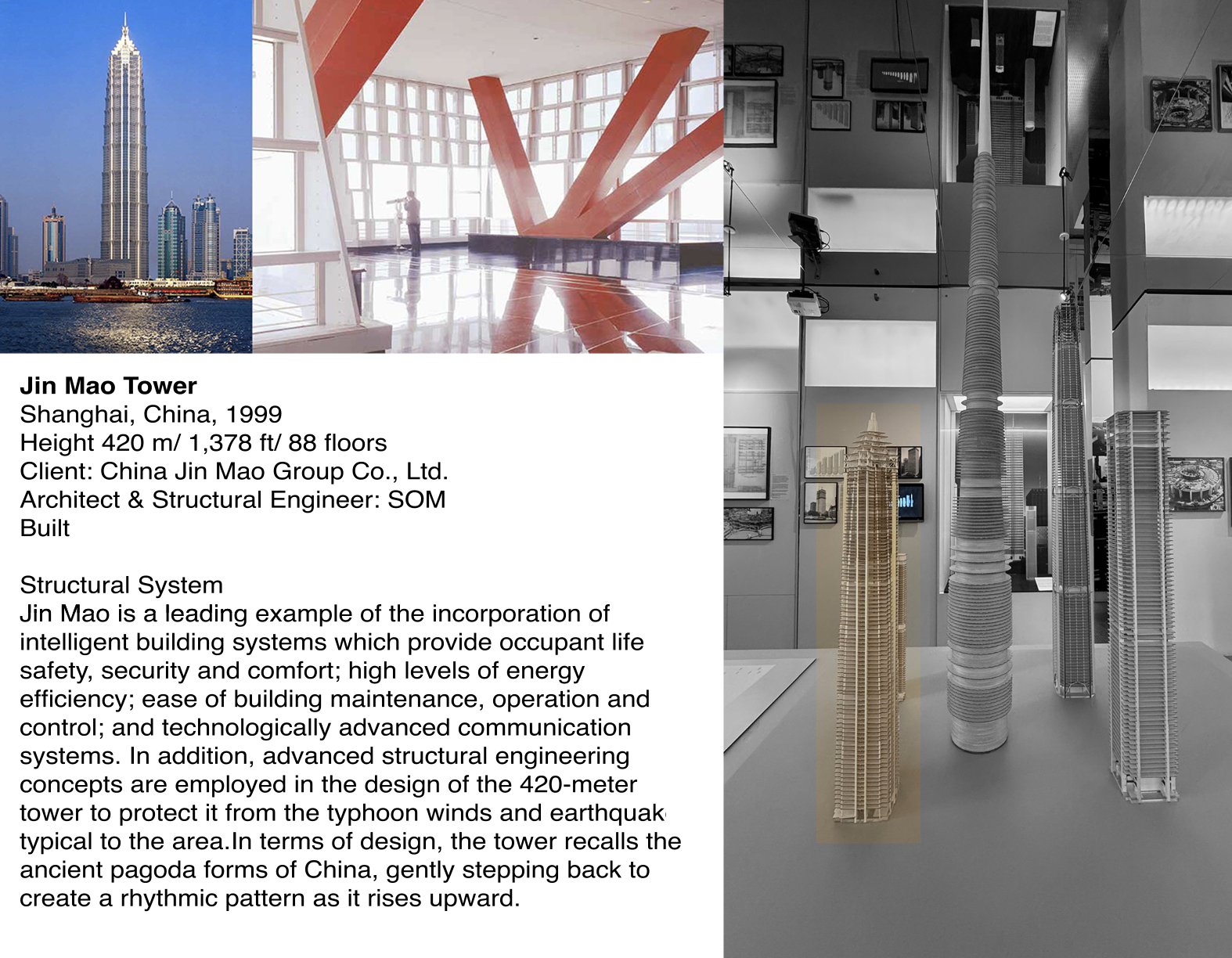

Meanwhile, the race for record-breaking height moved beyond the U.S. to Southeast Asia, China, and the Middle East – mainly through the expertise of American architects and engineers. The buildings that first illustrated this global competition were the Petronas Towers in Kuala Lumpur. Cesar Pelli and Thornton Tomasetti continued their collaboration by designing twin towers, dramatically linked by a skybridge that symbolized a gateway and which, at 1,483 ft./ 452 m. to the tips of their spires, stole the title of world’s tallest building from Chicago’s Sears Tower. Concrete was chosen because Malaysia had no national steel industry, but already by the 1990s, concrete was becoming the standard material for supertall construction. In Shanghai, the 88-story Jin Mao Tower, designed and engineered by SOM and completed in 1999, was the first of China’s supertalls. Jin Mao’s massive octagonal core, which hollowed out into a soaring atrium, artfully expressed the malleability of concrete.

Foundations also used massive amounts of concrete. In fluid or muddy soil, as in Shanghai, thick mat foundations were generally supported by hundreds of friction piles. These long, thin cylinders filled with concrete often extended down 150 to 300 feet to create surface resistance along their lengths. The core of Jin Mao, for example, rises from a 4-meter concrete mat that transfers the tower loads to more than 1,000 bearing piles. In cities with deep bedrock, such as Chicago, concrete caissons continued to be used. At 311 S. Wacker, caissons 6 to 8 feet in diameter stretched 92 ft. to find a solid stratum. Concrete’s resistance to water and high compressive strength make it ideal for piles and caissons.

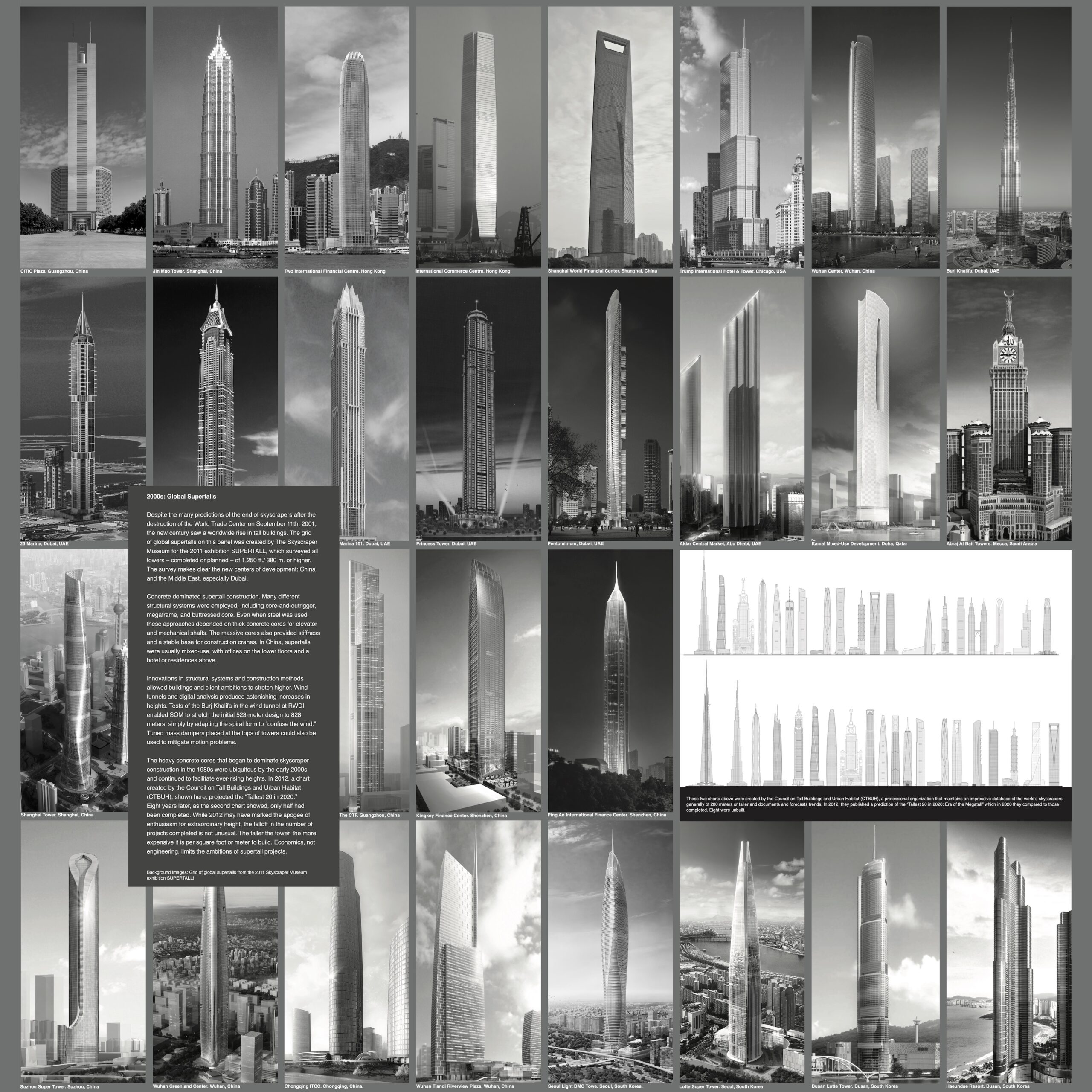

The grid of skyscrapers in this panel was created for the Museum's past exhibition, Supertall! The two charts of skyscraper elevation drawings are courtesy of CTBUH.

2000s: Global Supertalls

Despite the many predictions of the end of skyscrapers after the destruction of the World Trade Center on September 11th, 2001, the new century saw a worldwide rise in tall buildings. The grid of global supertalls on this panel was created by The Skyscraper Museum for the 2011 exhibition SUPERTALL, which surveyed all towers – completed or planned – of 1,250 ft./ 380 m. or higher. The survey makes clear the new centers of development: China and the Middle East, especially Dubai.

Concrete dominated supertall construction. Many different structural systems were employed, including core-and-outrigger, megaframe, and buttressed core. Even when steel was used, these approaches depended on thick concrete cores for elevator and mechanical shafts. The massive cores also provided stiffness and a stable base for construction cranes. In China, supertalls were usually mixed-use, with offices on the lower floors and a hotel or residences above.

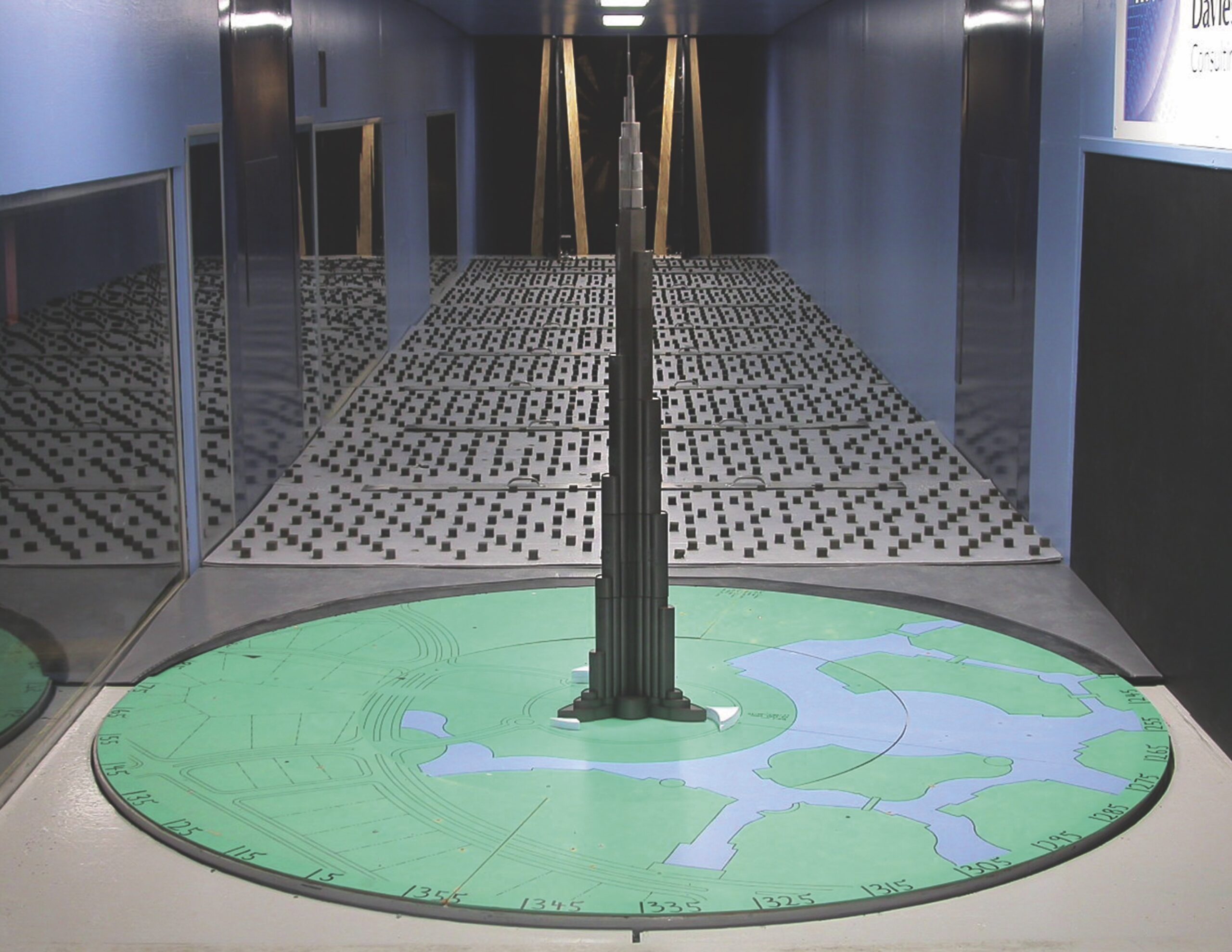

Innovations in structural systems and construction methods allowed buildings and client ambitions to stretch higher. Wind tunnels and digital analysis produced astonishing increases in heights. Tests of the Burj Khalifa in the wind tunnel at RWDI enabled SOM to stretch the initial 523-meter design to 828 meters. simply by adapting the spiral form to “confuse the wind.” Tuned mass dampers placed at the tops of towers could also be used to mitigate motion problems.

The heavy concrete cores that began to dominate skyscraper construction in the 1980s were ubiquitous by the early 2000s and continued to facilitate ever-rising heights. In 2012, a chart created by the Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat (CTBUH), shown here, projected the “Tallest 20 in 2020.” Eight years later, as the second chart showed, only half had been completed. While 2012 may have marked the apogee of enthusiasm for extraordinary height, the falloff in the number of projects completed is not unusual. The taller the tower, the more expensive it is per square foot or meter to build. Economics, not engineering, limits the ambitions of supertall projects.

Background Images: Grid of global supertalls from the 2011 Skyscraper Museum exhibition SUPERTALL!

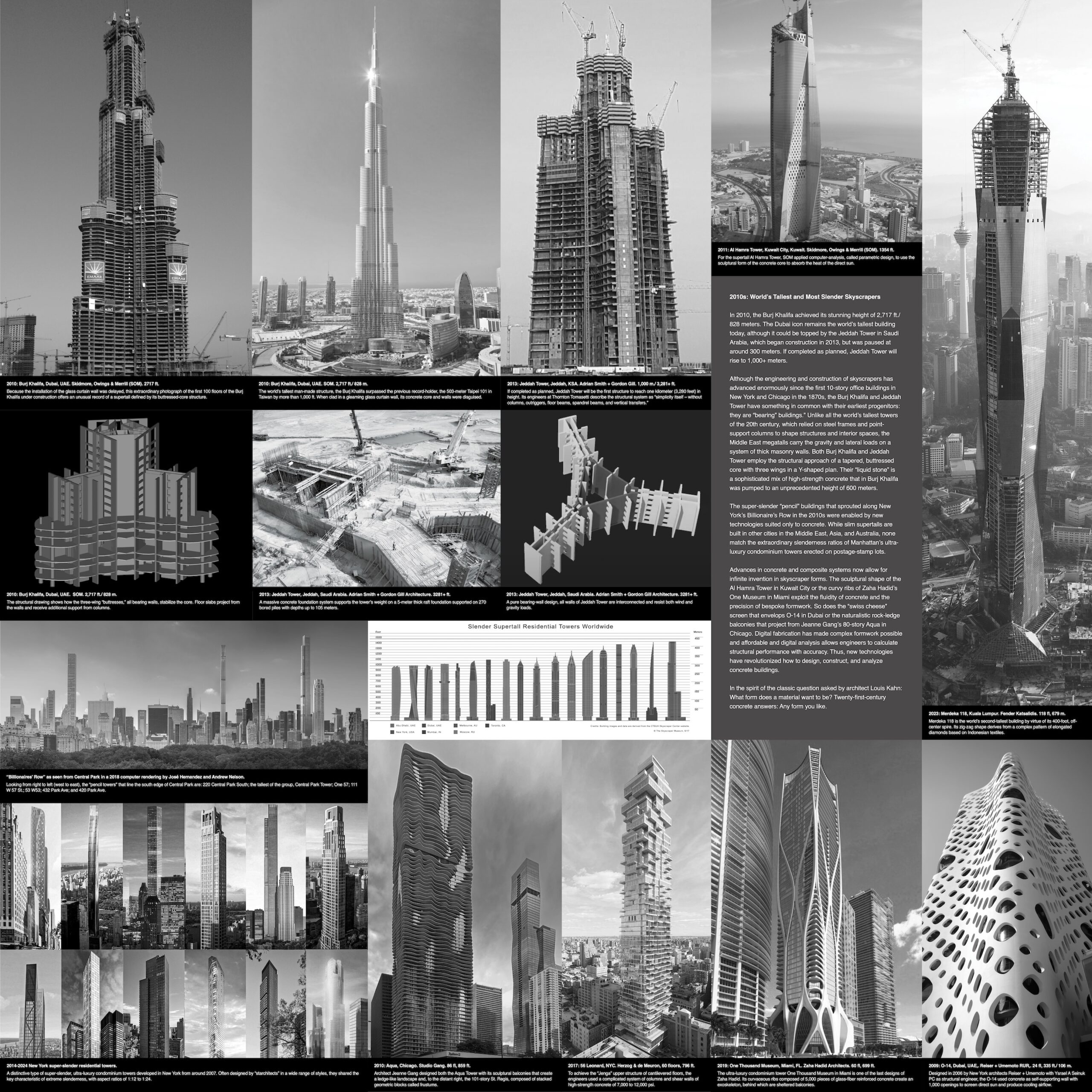

2010s: World's Tallest and Most Slender Skyscrapers

In 2010, the Burj Khalifa achieved its stunning height of 2,717 ft./ 828 meters. The Dubai icon remains the world’s tallest building today, although it could be topped by the Jeddah Tower in Saudi Arabia, which began construction in 2013, but was paused at around 300 meters. If completed as planned, Jeddah Tower will rise to 1,000+ meters.

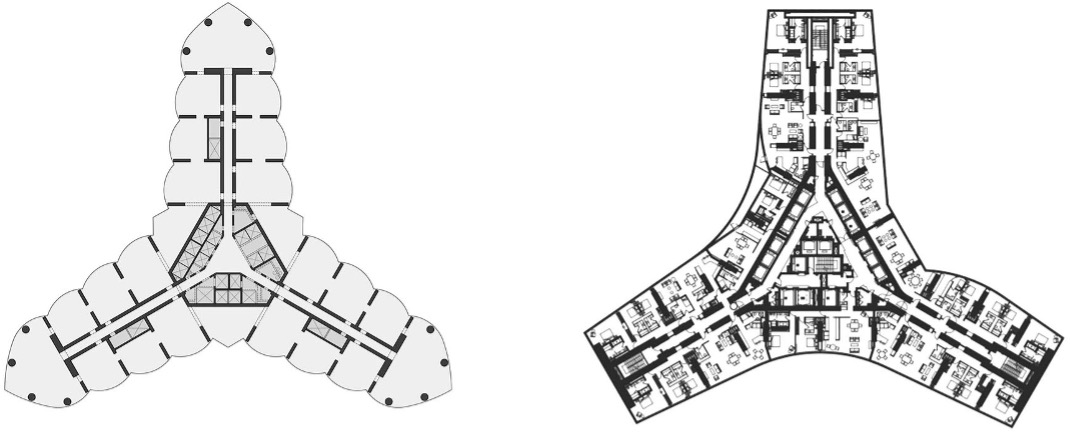

Although the engineering and construction of skyscrapers has advanced enormously since the first 10-story office buildings in New York and Chicago in the 1870s, the Burj Khalifa and Jeddah Tower have something in common with their earliest progenitors: they are “bearing” buildings.” Unlike all the world’s tallest towers of the 20th century, which relied on steel frames and point-support columns to shape structures and interior spaces, the Middle East megatalls carry the gravity and lateral loads on a system of thick masonry walls. Both Burj Khalifa and Jeddah Tower employ the structural approach of a tapered, buttressed core with three wings in a Y-shaped plan. Their “liquid stone” is a sophisticated mix of high-strength concrete that in Burj Khalifa was pumped to an unprecedented height of 600 meters.

The super-slender “pencil” buildings that sprouted along New York’s Billionaire’s Row in the 2010s were enabled by new technologies suited only to concrete. While slim supertalls are built in other cities in the Middle East, Asia, and Australia, none match the extraordinary slenderness ratios of Manhattan’s ultra-luxury condominium towers erected on postage-stamp lots.

Advances in concrete and composite systems now allow for infinite invention in skyscraper forms. The sculptural shape of the Al Hamra Tower in Kuwait City or the curvy ribs of Zaha Hadid’s One Museum in Miami exploit the fluidity of concrete and the precision of bespoke formwork. So does the “swiss cheese” screen that envelops O-14 in Dubai or the naturalistic rock-ledge balconies that project from Jeanne Gang’s 80-story Aqua in Chicago. Digital fabrication has made complex formwork possible and affordable and digital analysis allows engineers to calculate structural performance with accuracy. Thus, new technologies have revolutionized how to design, construct, and analyze concrete buildings.

In the spirit of the classic question asked by architect Louis Kahn: What form does a material want to be? Twenty-first-century concrete answers: Any form you like.

Prologue: Concrete Construction 1900-1950

One wall of the exhibition focuses on the first half of the 20th century, when concrete was ubiquitous, but not conspicuous in skyscrapers. There were only a few experiments in fully reinforced-concrete high-rises and those remained virtual one-offs, like the Ingalls building in Cincinnati or the Royal Liver Building in Liverpool, England, both featured on the wall. Yet, concrete was present and essential in every high-rise building, and in fact was often the dominant material, if measured by weight. The pervasive presence of concrete in steel-skeleton buildings is illustrated in a suite of photographs of the Empire State Building that picture foundations, floors, and fireproofing, among other key uses.

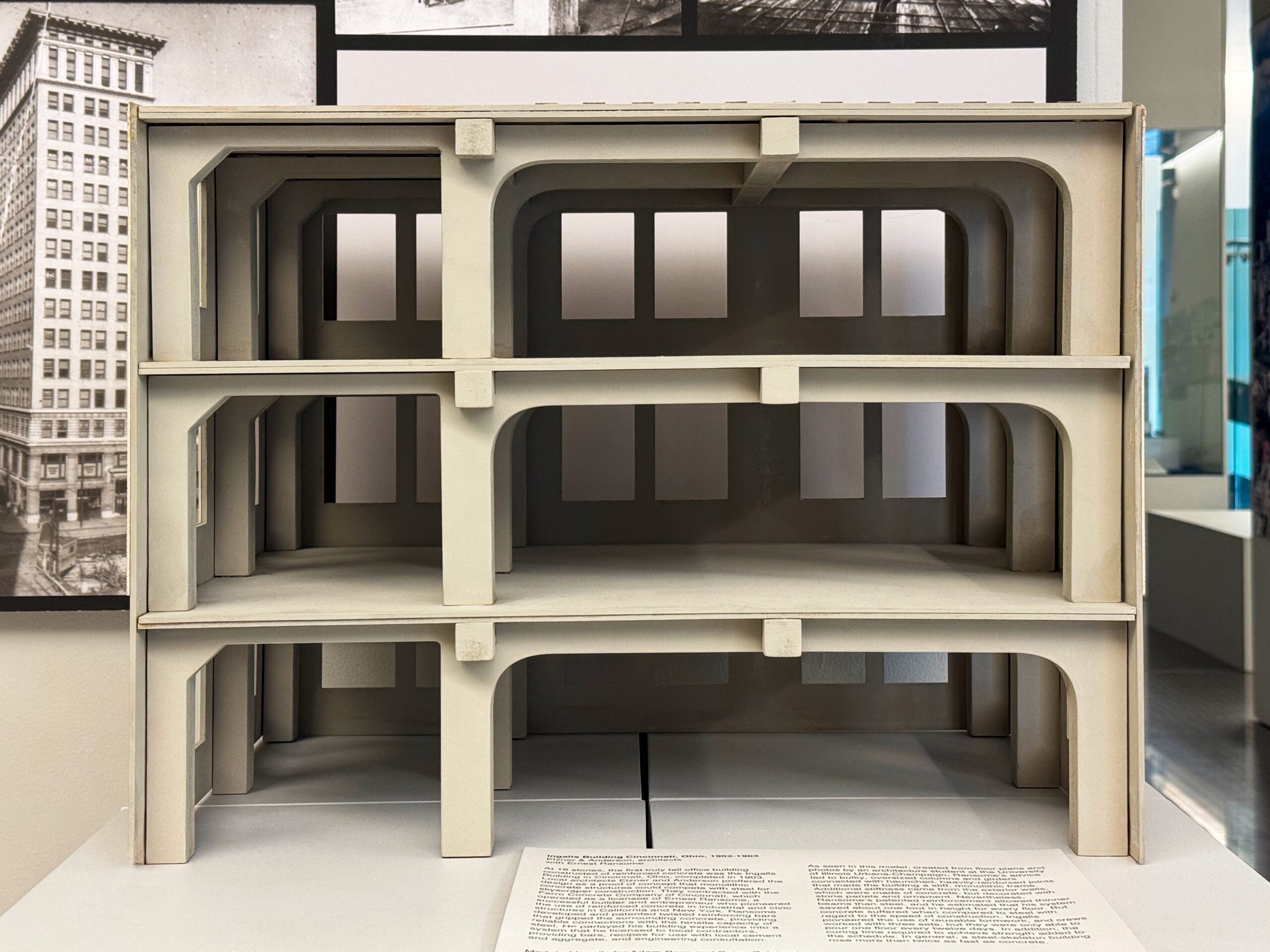

Ingalls Building, Cincinnati, Ohio, 1903

64 m/ 210 ft/ 16 floors

Architect: Elzner & Anderson, with Ernest Ransome

Retrofit Architect: Luminaut

Photographs from the Collection of Cincinnati & Hamilton County Public Library and Architectural Record (June 1904)

Model of Ingalls building by Adam Berg and Paige Zolnierek from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign

Ingalls Building

At 16 stories, the Ingalls Building in Cincinnati, Ohio, can legitimately be called “the first concrete skyscraper,” a proof-of-concept that demonstrated the new material could be relied upon for strength and stiffness at heights that competed with steel. Local architects Elzner and Anderson contracted with the Ferro Concrete Company of Cincinnati, who had built several low-rise concrete structures in the city. The company operated as a licensee of Ernest Ransome, a successful builder and entrepreneur who pioneered the use of reinforced concrete in industrial and civic structures in California and New York. Ransome developed patented twisted reinforcing bars that gripped the surrounding concrete, providing reliable connections with the tensile capacity of steel. He parlayed his building experience into a system he licensed to local contractors, providing bars, recipes for use with local cement and aggregate, and engineering consultation. The photographs on the left show the process of construction on the exterior as the building rises as well as for interior staircases, floors, and columns.

As seen in the model, created from floor plans and photos by architecture students at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, Ransome’s advice led to bulky, oversized columns and girders connected with haunched, heavily-reinforced joints that made the building a stiff, monolithic frame. Additional stiffness came from the exterior walls, which were made of concrete, but decorated with stone panels and ornament. Nevertheless, Ransome’s patented reinforcement allowed thinner beams than steel, and he estimated that his system saved about one foot in height for every floor. But concrete suffered when compared to steel with regard to the speed of construction. Ingalls pioneered the use of reusable formwork, and crews worked with three sets, but they were only able to pour one floor every twelve days. In addition, the curing time required to achieve strength added to the schedule. In general, a steel-skeleton building rose more than twice as fast as concrete.

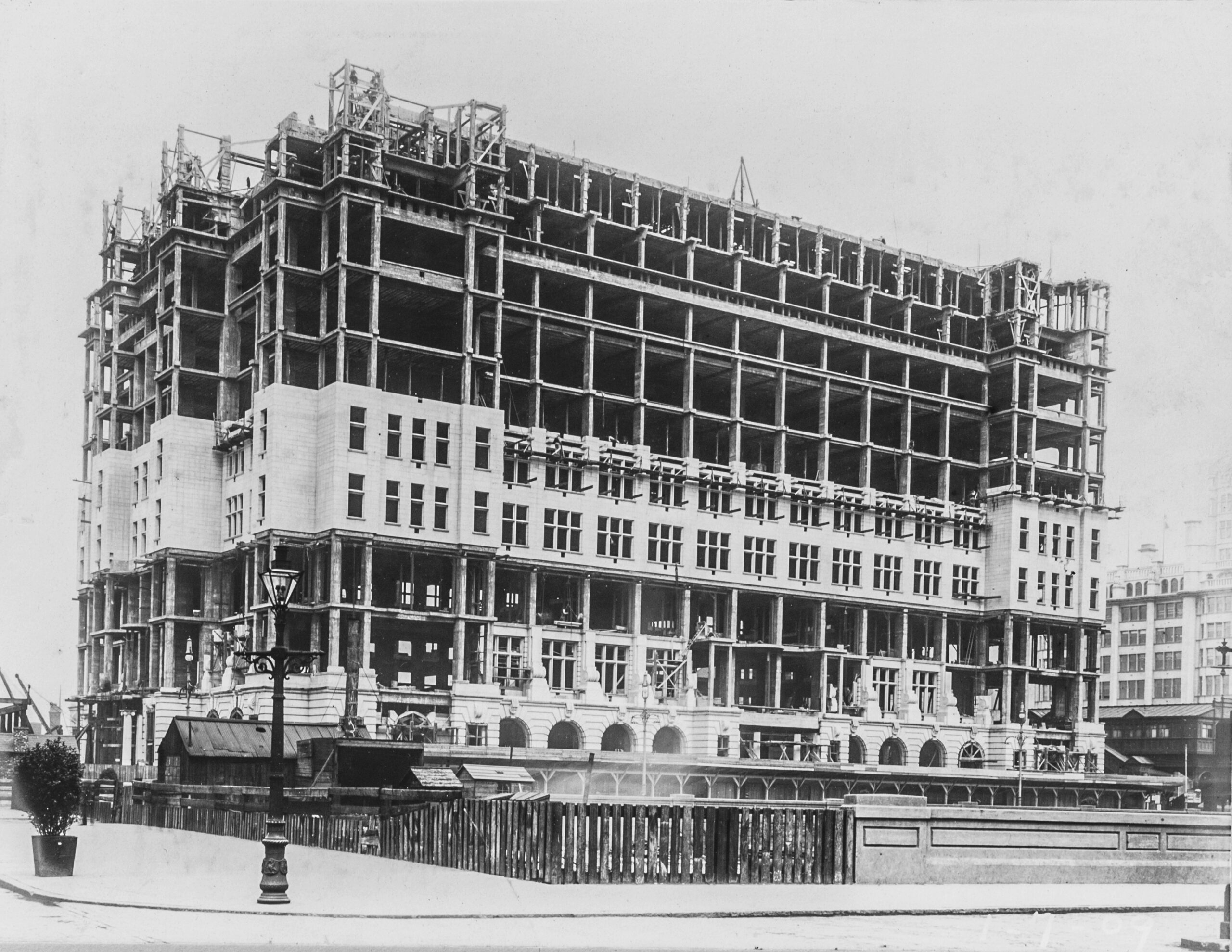

Royal Liver Building, Liverpool, England, 1908-1911

98 m/ 322 ft/ 13 floors

Architect: Walter Aubrey Thomas

Client: Royal Liver Assurance Group

Photographs courtesy of Liver Building CoLtd.

Royal Liver Building

The Royal Liver Building was among the most prominent and tallest structures built using the Hennebique system of reinforced concrete construction, which treated the material as a column-and-beam system. Developed by the French builder Francois Hennebique in 1892, this system used steel reinforcement bars in patented shapes to connect columns and girders with strong, stiff joints. The resulting frames were ‘self-braced’; they resisted gravity and wind forces by themselves, without additional shear walls. Used throughout Europe mostly to build factories, warehouses, and industrial structures, the Hennebique system was the most successful patented system in Europe. By 1900, the company had erected more than 1,500 projects annually.

The construction photographs here show how the Hennebique system mimicked the skeletal appearance of steel framing. Concrete formed floors, columns, girders, and walls—even a spiral staircase leading to the clock towers. The deep girders conceal heavy steel reinforcing that helps direct loads into the thin columns, while thick shear walls toward the base help stay the building against wind. The middle image in the slideshow on the left shows formwork (the upside-down trays) being laid to mold one-way joists that will carry floor loads to the deeper girders while minimizing the overall weight. In the other two images, granite cladding is hung from the concrete frame, concealing it entirely and presenting a more formal appearance to the rest of the city. Hennebique’s work typically consisted of this ‘hidden structure’ behind a stone or masonry veneer.

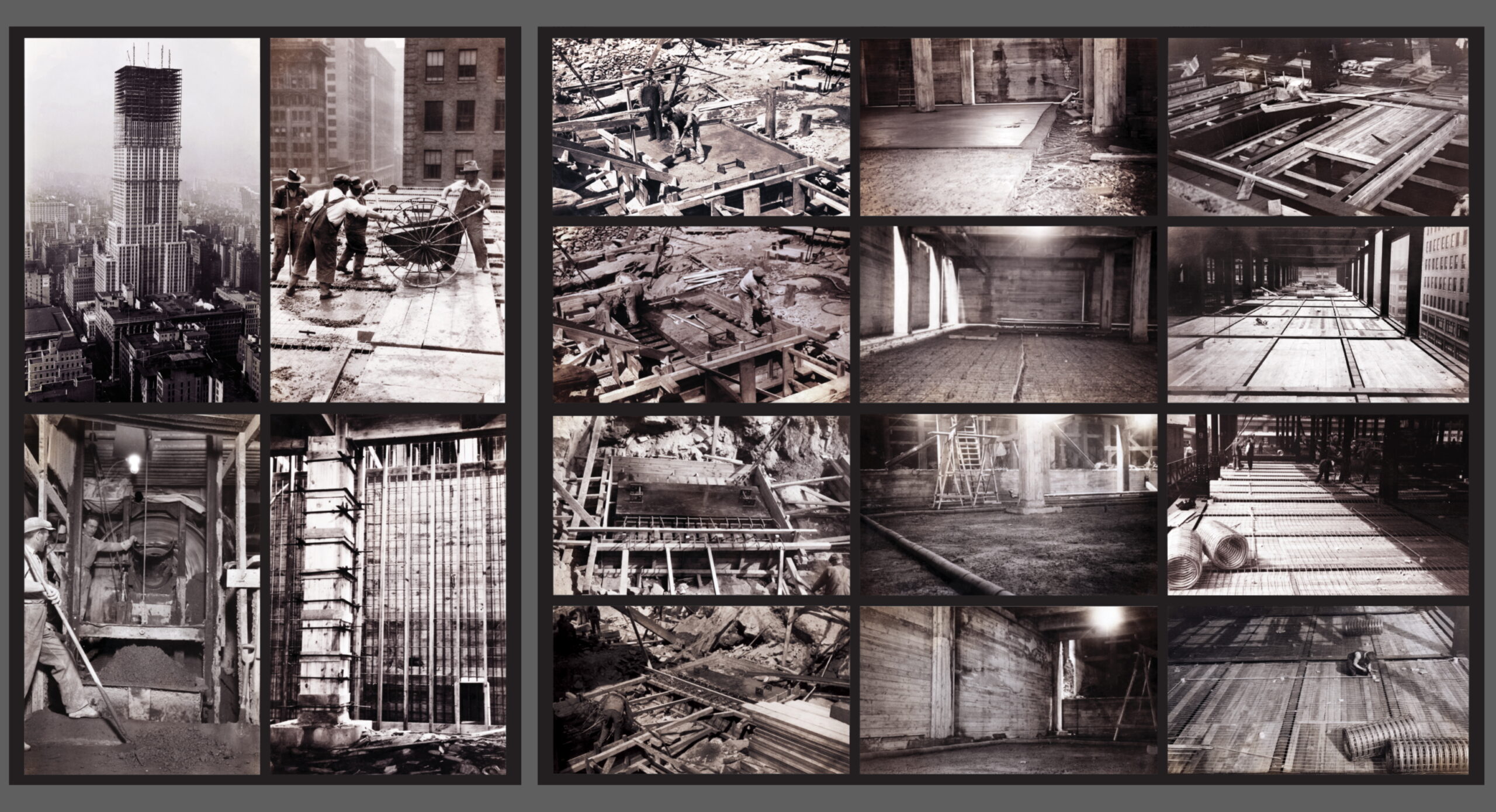

Empire State Building

Through the 1930s, even in a nominally steel building, concrete had a major presence, as this selection of photographs of the Empire State Building in the Museum's collection illustrate. The steel columns and beams that arrived like clockwork on the Empire State Building’s job site were accompanied by an average of 5,000 cement bags daily.

Concrete was vital to the structure’s 210 massive caisson foundations and thick basement walls. It also was used to create floor slabs by pouring light-weight cinder aggregate over draped steel mesh. Although the concrete was mixed on site, standardized wooden formwork allowed speedy construction. Concrete also encased and fireproofed the steel frame. Crews followed ironworkers, casting shallow concrete jackets around each column. Despite its long curing times, concrete played a crucial role in the record-breaking, 11-month construction of the Empire State Building.

The images in the adjacent panels are from the Museum's collection of 511 Empire State Building construction views, as documented in a scrapbook by the original contractors and accessible online through the Visual Index to the Virtual Archive.

Left Panel Images (left to right):

- Steel--72nd floor; metal trim--60th floor; floor arches--65th floor; stone--51st floor (9/3/1930)

- Concreting--6th floor setback (5/22/1930)

- Concrete mixer and hoist bucket (10/22/1930)

- Column forms clamped (5/12/30)

Right Panel Images (left to right):

- Leveling surface mixture (4/5/1930)

- 2nd basement floor (7/8/1930)

- Side and slab forms (5/6/1930)

- Spreading grout around grillage (4/5/1930)

- Concrete runways (6/11/1930)

- Slab forms--5th floor (5/17/1930)

- Wood around grillage (4/5/1930)

- Weeper on cinder concrete base (6/11/1930)

- Slab forms with mesh and conduit (5/7/1930)

- Boxed grillages wet down before grouting (4/5/1930)

- Weepers on base concrete (6/11/1930)

- Running conduit over mesh (5/7/1930)

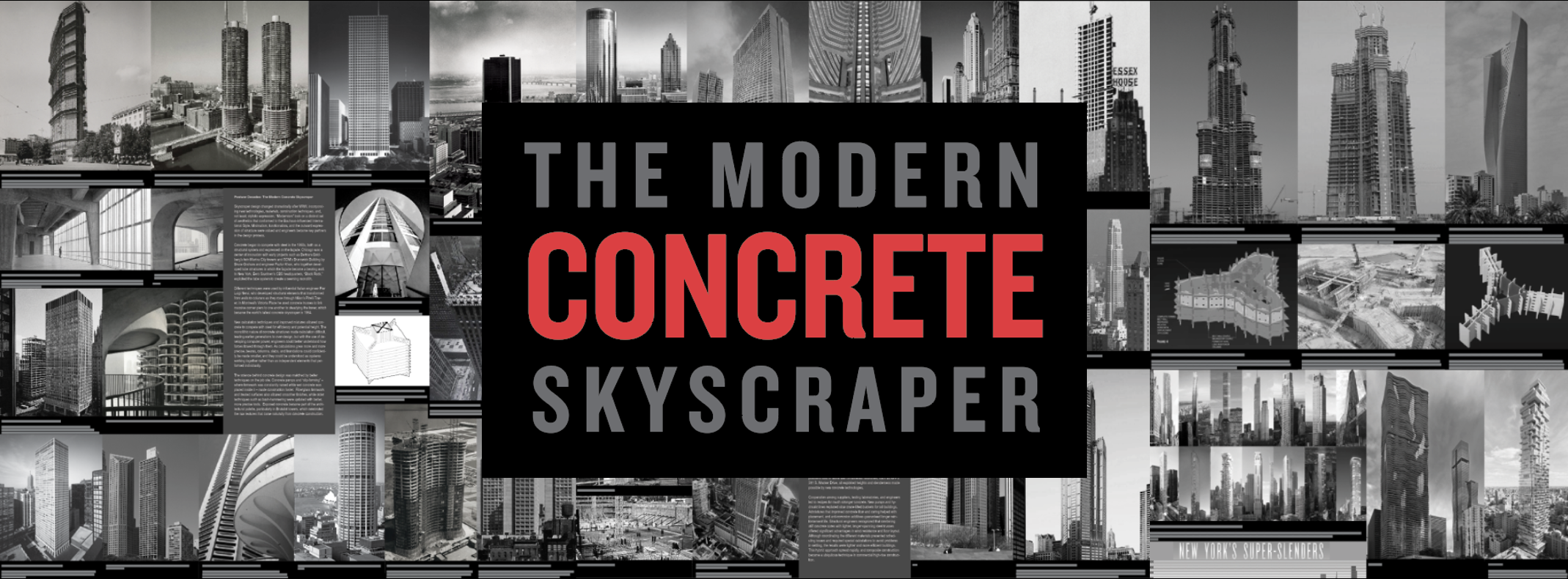

The Modern Concrete Skyscraper

The main gallery focuses on the second half of the 20th century to the present day. The buildings featured are “case studies” that represent both the importance of key designers – and generally the intimate collaborations of architects and engineers – and the impact of new technologies in materials and advances in construction that, from the 1980s, allowed for greater heights, slenderness, and formal expression.

The post-WWII decades were characterized by the triumph of Modernism, both as an aesthetic and an ideology connected to simplicity of forms and expression of structure, and to an avoidance of applied ornament, but value of the intrinsic beauty of materials. While the “glass box” model of Lever House or the Seagram Building became the dominant approach for the postwar skyscrapers, some architects and engineers began to explore structural systems in reinforced concrete that offered striking contrasts to steel skeletons and glazed curtain walls. Buildings such as Marina City, One Shell Plaza, the CBS headquarters “Black Rock”, and One Australia Square illustrate the range of expression that could be achieved in concrete while exploring the principles of Modernism.

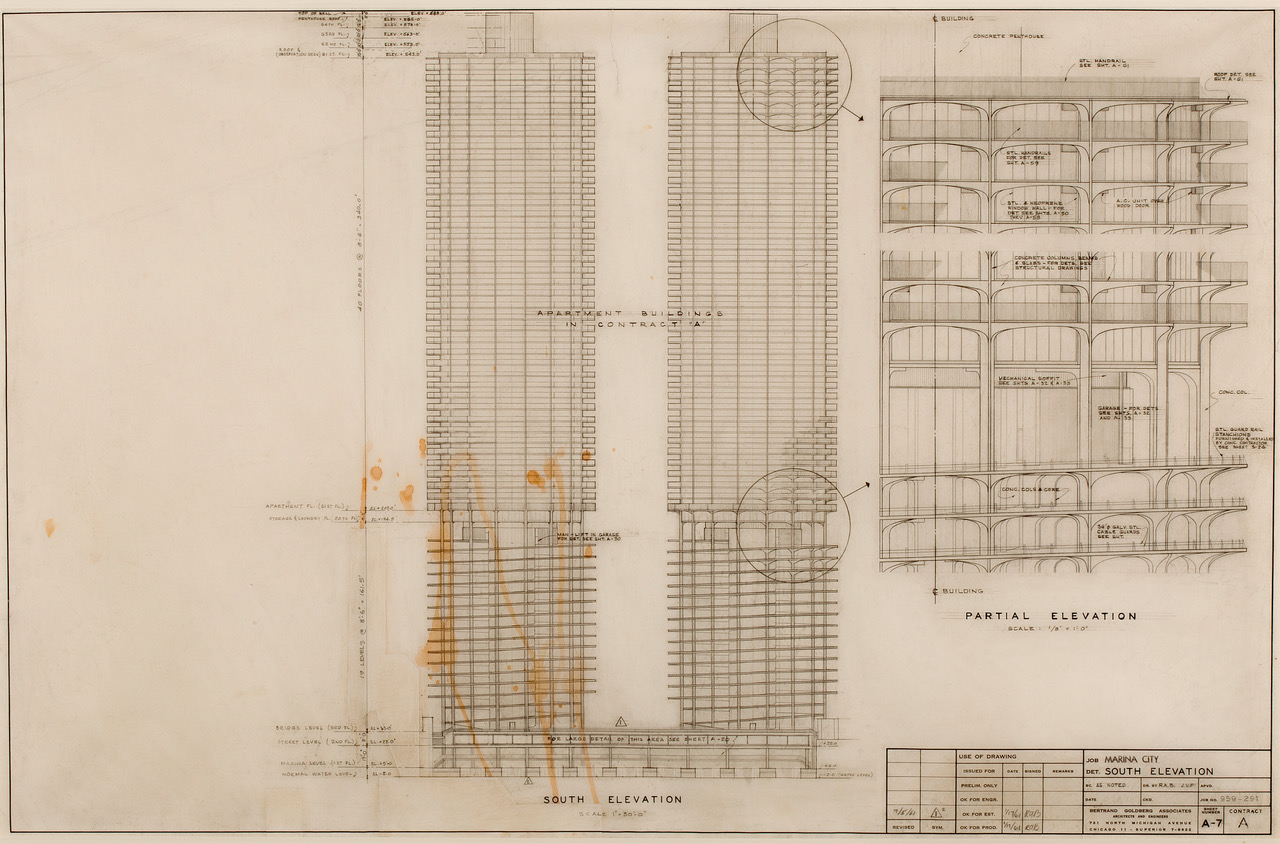

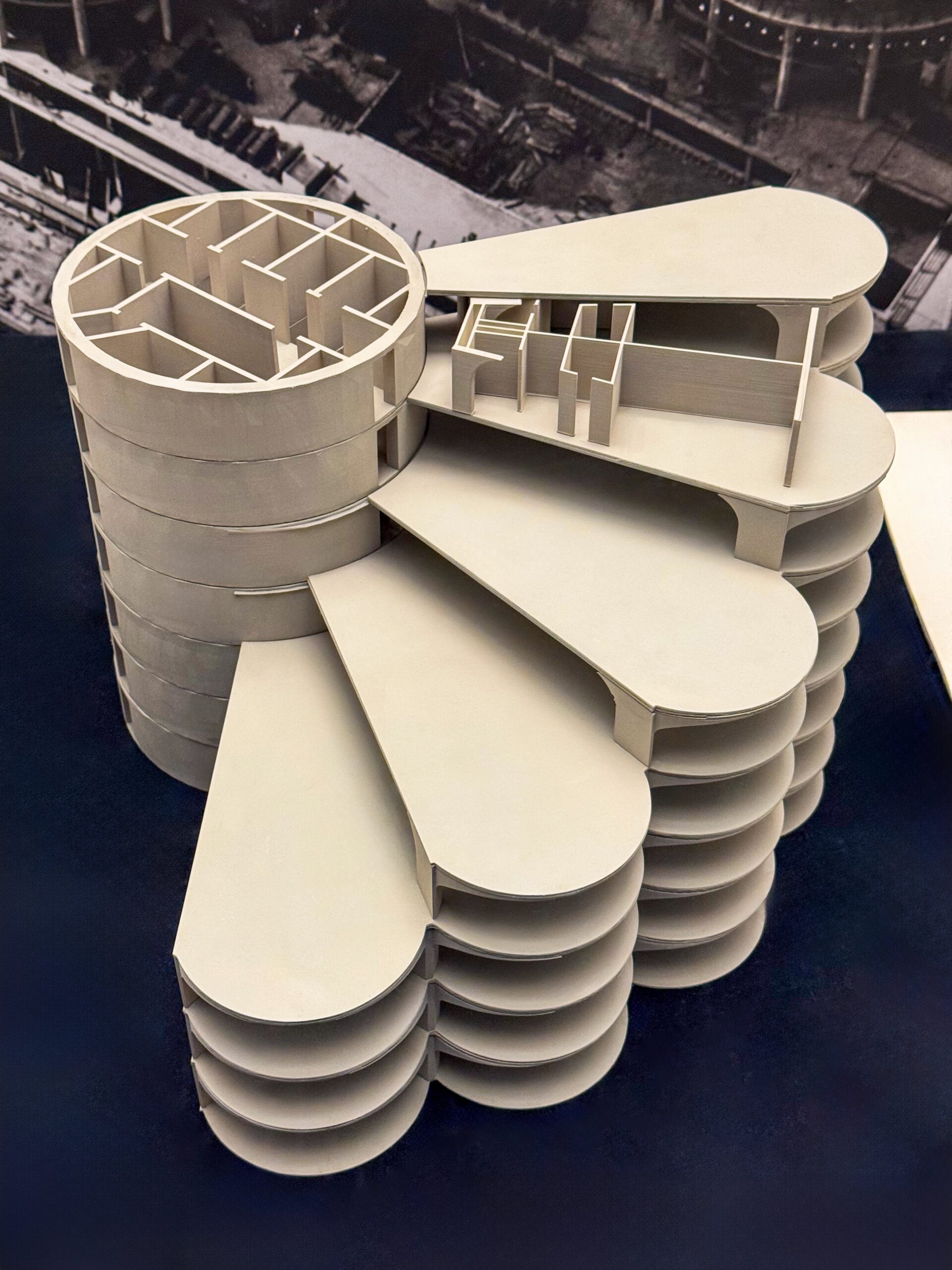

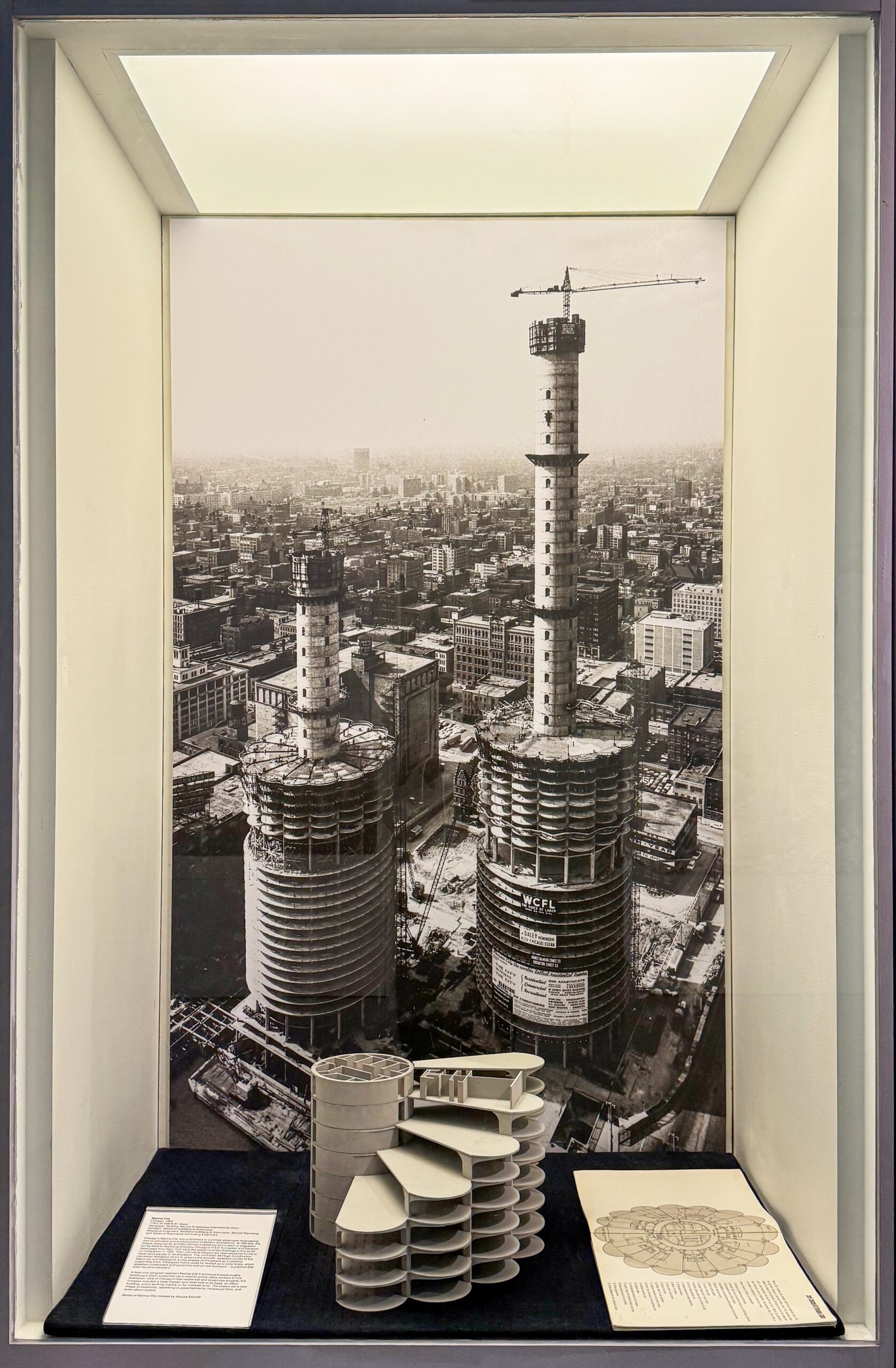

Marina City, Chicago, 1962

179.2 m/ 588 ft/ 61 floors

Architect: Bertrand Goldberg & Associates

Structural Engineer: Bertrand Goldberg & Associates, Bertold Weinberg, and Severud Associates Consulting Engineers

Developer: Building Service Employees International Union

Marina City model by Atousa Esmaili from the Univeristy of Illinois Urbana-Champaign

Portland Cement Association. 1965. This Is Marina City (excerpt from 19 min video). Chicago, IL. Courtesy of Portland Cement Association (PCA).

To learn more about Marina City and how its construction used concrete toward important social and political ends in the early 1960s, watch this lecture for the Museum by Geoffrey Goldberg, the son of the towers' architect Bertrand Goldberg.

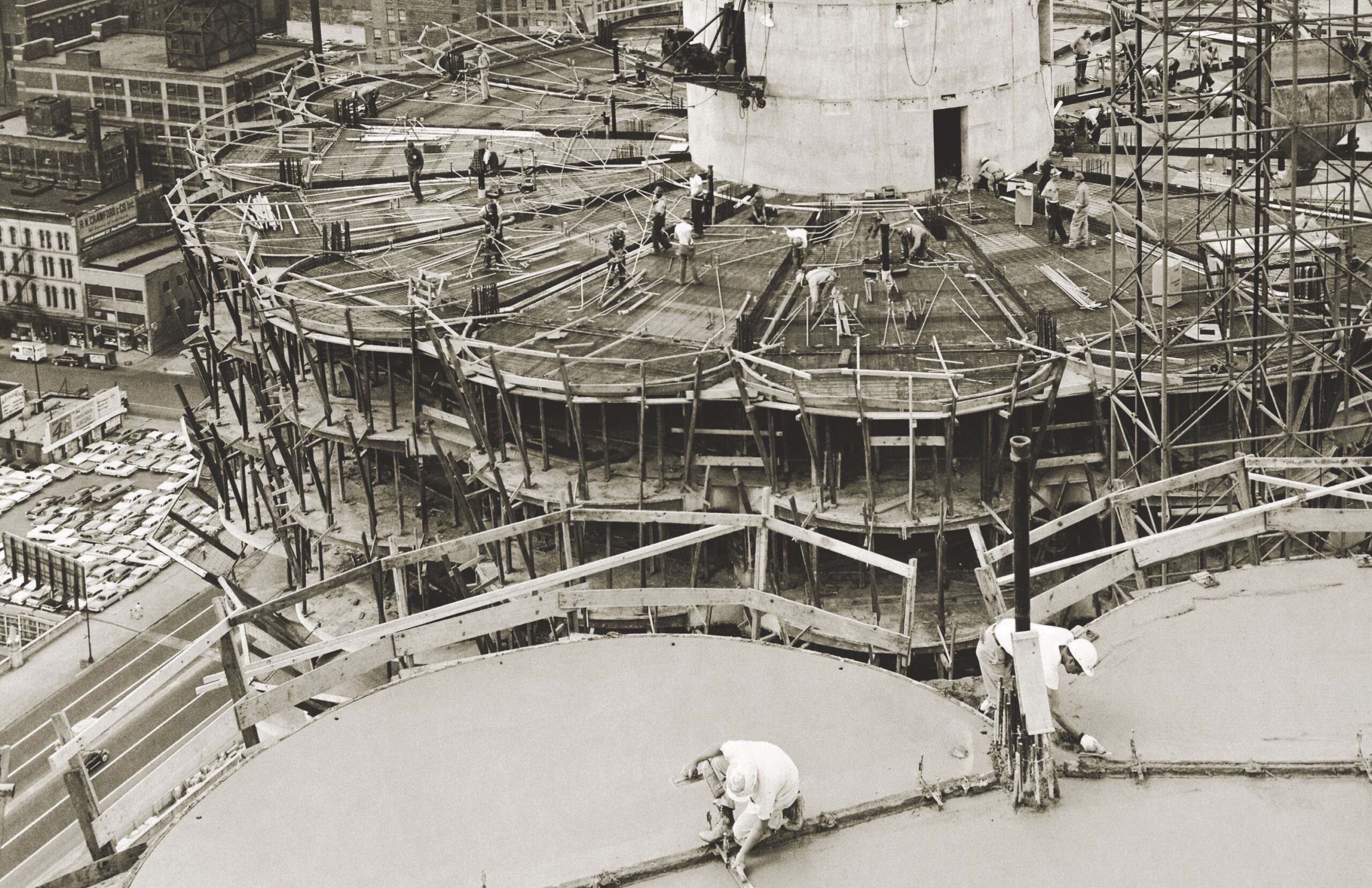

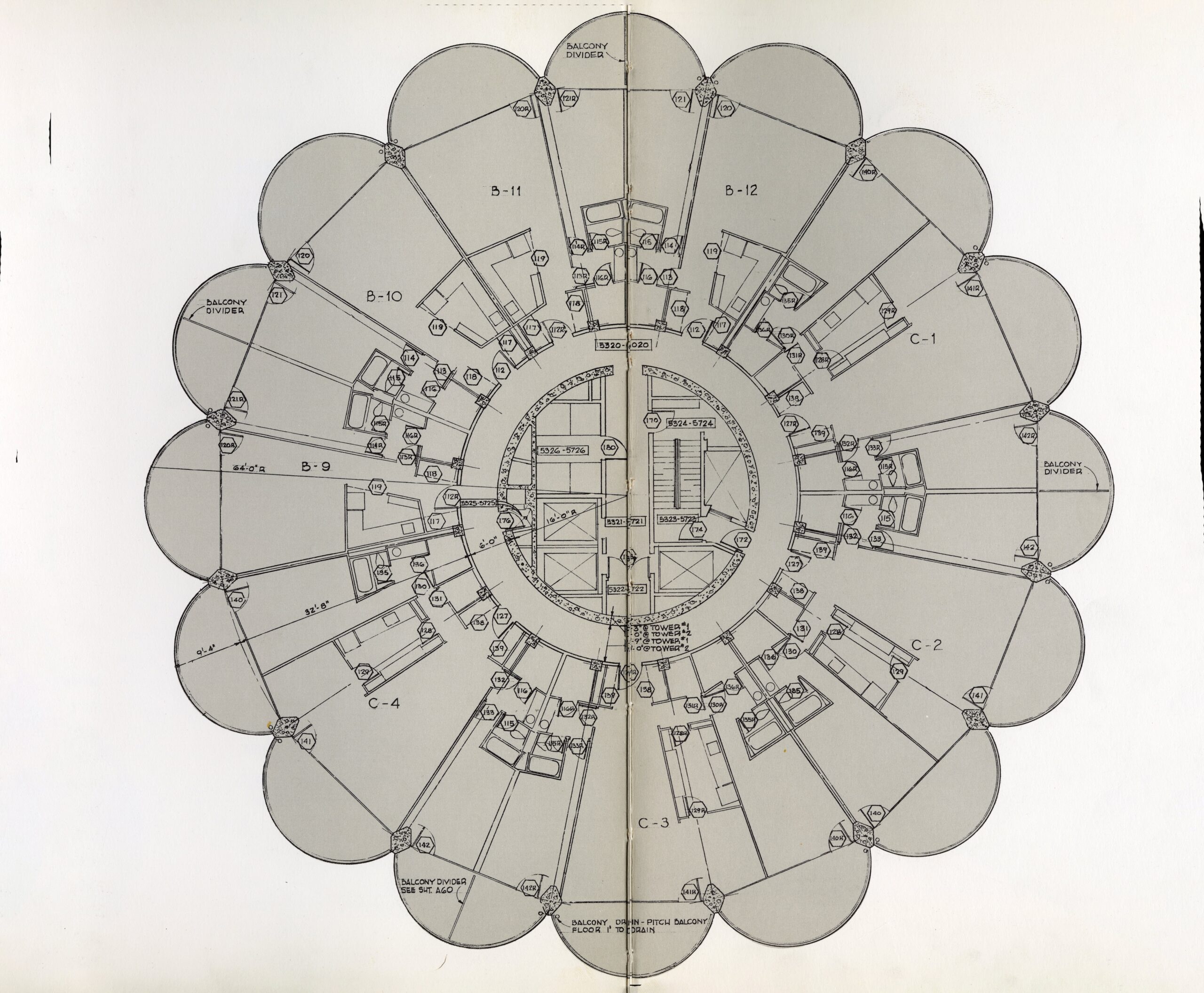

Marina City

Chicago’s Marina City was a landmark in concrete skyscraper engineering and construction and a masterpiece of Modern architecture. At 588 feet, the two towers, designed by Bertrand Goldberg and a team of engineers led by Bertold Weinberg that included Chicago’s Frank Kornacker and Severud Associates, from New York, were the tallest concrete towers in the world when they opened in 1962. Their cylindrical shapes are ideal structural forms to resist wind equally in all directions. The contractor, McHugh Construction, pioneered fiberglass forms to achieve the smooth, repetitive curves of the balconies and expressive arcing shapes of the girders and columns supporting them. Fiberglass could be reused up to sixty times, which speeded construction and saved the cost of new formwork – a practice that soon became standard.

A bold civic program matched Marina City’s technical breakthroughs. Goldberg’s vision suited the city’s need to entice office workers to live downtown. One of Chicago’s first residential and mixed-use projects, the complex included a large theater and retail mall at its base, an office building, and a working marina on its riverside level. The towers set a new image of modernity, and the popular towers appeared in advertisements, Hollywood films, and even album covers.

Marina City’s construction was highly dramatic and complex, as the 1963 film produced by the Portland Cement Association, “This is Marina City,” an excerpt of which is to the left, records. The towers’ concrete caisson foundations, designed by Ralph Peck, had to be drilled through nearly 100 feet of thick, fluid clay before reaching bedrock. The caissons were tied together by a large underground mat, which served as the base for the cores and columns. Swiveling tower cranes took advantage of the circular core and plans, extending the radius up to 90 ft. and lifting themselves up the cores ahead of the floor slabs.

Fiberglass formwork and prefabricated steel reinforcing cages sped construction. McHugh Construction completed a floor every two days using three stories of formwork; once a floor was poured, it would cure to a reasonable strength in just under a week, allowing workers to strip the forms and ‘jump’ them three stories above to the next pour. The twin towers were completed in just two years, setting records for height and speed.

Marina City’s display of concrete’s affordability and ability to create a wide variety of forms and spaces helped inspire a generation of experimentation in reinforced concrete.

Brunswick Building, Chicago, 1964

144.8 m/ 475 ft/ 35 floors

Architect: Skidmore, Owings & Merrill

Photo courtesy of SOM

Chestnut-Dewitt, Ch, Chicago, 1966

120.4 m/ 395 ft/ 43 floors

Architect: Skidmore, Owings & Merrill

Photo by Hedrich Blessing Photographers

Concrete Structural Systems for Office Buildings" diagram by Fazluer Khan, 1967.

Courtesy of SOM.

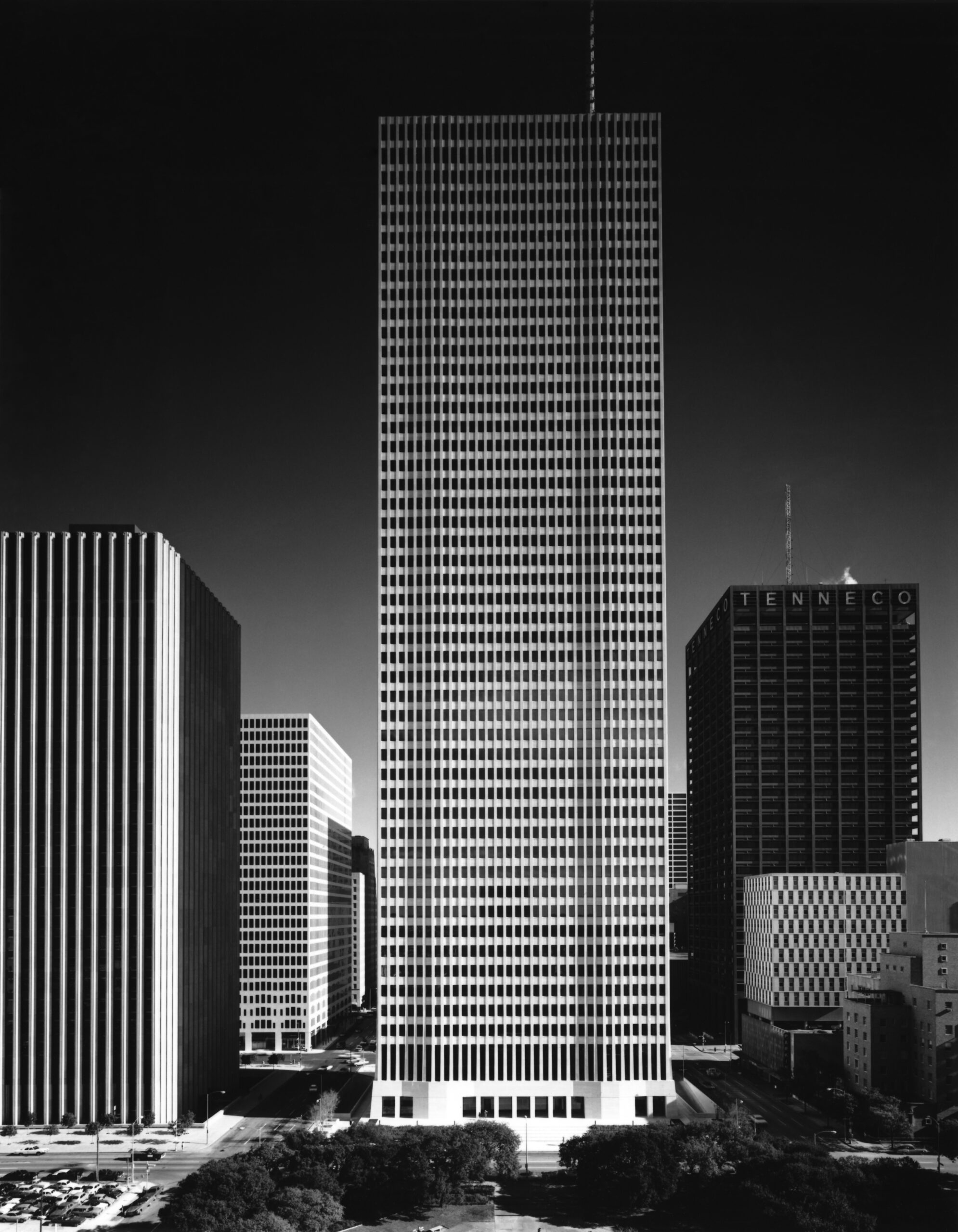

One Shell Plaza, Houston, 1970

217.6 m/ 715 ft/ 50 floors

Architect: Skidmore, Owings & Merrill

First photo by Ezra Stoller | Esto, second photo courtesy of Hines

Guiyang World Trade Center, China, 2021

380 m/ 1,247 ft/ 92 floors

Architect: Skidmore, Owings & Merrill

Rendering courtesy of SOM

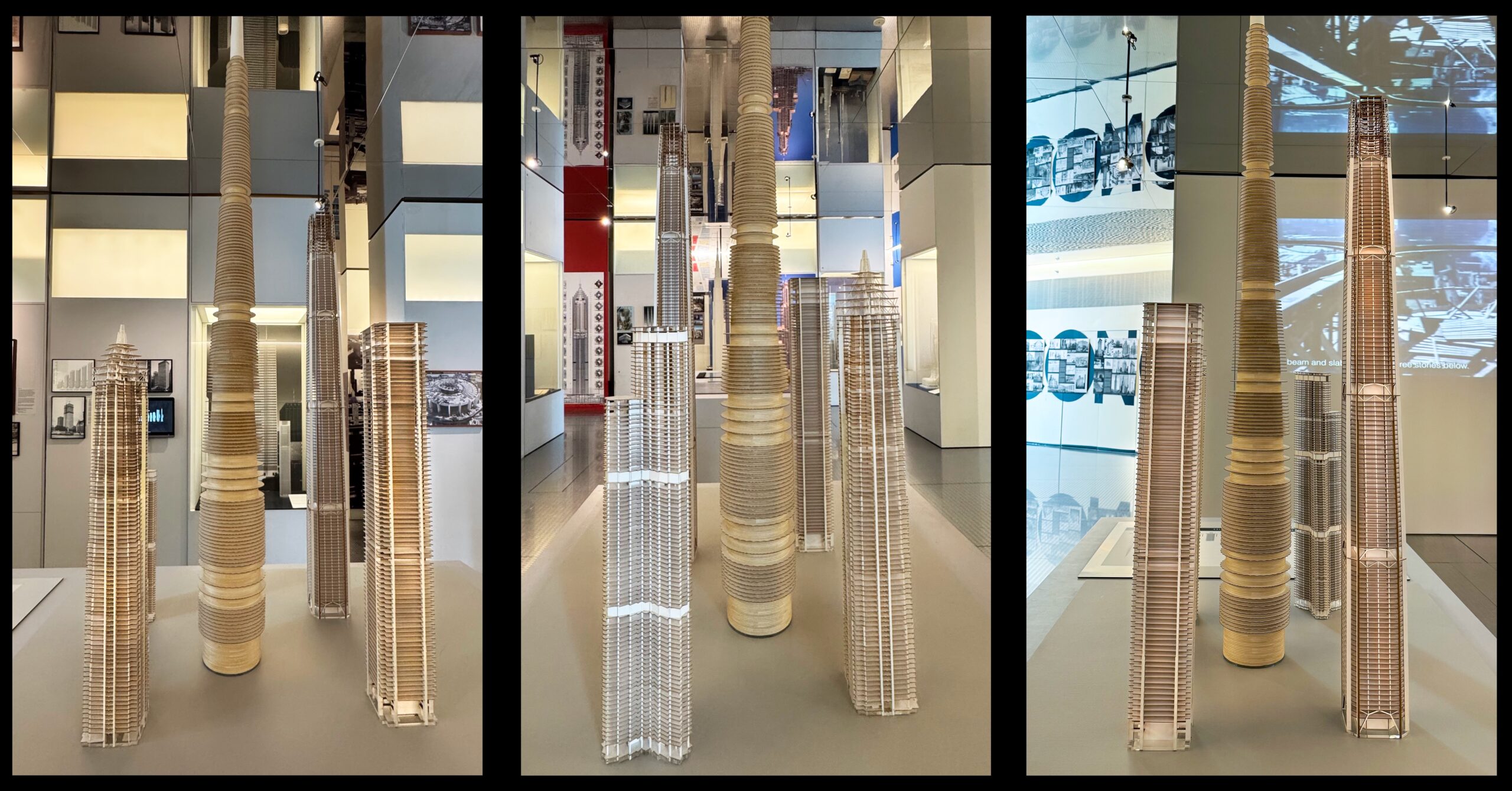

The Concrete Tube: Fazlur Khan and his Legacy

One of the key innovations in skyscraper design in the 1960s was the concept of the tube, in which the structure is concentrated in the exterior wall or perimeter columns, turning the building, in effect, into a giant hollow column that can resist gravity and wind loads.The engineer Fazlur Khan was not the sole inventor of the “tube” structure for tall buildings, but he was its greatest innovator. A partner at SOM’s Chicago office from 1966, Khan joined the firm in 1955 while completing his PhD. on concrete structures at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. He was a key collaborator with SOM architects, especially architects Bruce Graham and Myron Goldsmith. Together they pioneered the concept of the tube, first in the Brunswick Building (1965) and Dewitt-Chestnut apartments (1966) in concrete, then in the John Hancock Center (1970) in steel.

In Khan’s concrete tubes, such as the One Shell Plaza in Houston (1971), the exterior walls are both rational and expressive. The bearing walls are sculpted to reflect how loads are collected throughout the structure, swelling outward around the base as the building’s weight is transferred over and around its main entrance. For the Onterie Centre in Chicago (center model), completed in 1986, Khan borrowed a 19th-century wind bracing technique, cross bracing, to turn its exterior tube structure into a rigid set of trusses that steady the building against wind.

More recently, SOM designed the Guiyang World Trade Center in Guiyang, China using advanced formwork techniques to achieve a tapering exterior tube in which the thickness of the concrete exterior wall works as both structure and a strategy for controlling solar gain. Although the tower was nearly topped out in 2021, construction has since been on hold. The three models shown in the case are part of a series created by SOM to illustrate the structural systems of key skyscrapers in their portfolio.

The video is an excerpt from the lecture by SOM partner Scott Duncan on his design for Guiyang WTC and the tube tradition at SOM. You can watch the full lecture as part of our WORLD VIEW lecture series about global supertalls here.

SOM Structural Models

The cardboard models in the show were created by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM) to illustrate the structural system of key skyscrapers designed by the firm from the 1960s to today. Originally made for an exhibition titled "SOM: Engineering x [Art + Architecture]" for the 2017 Chicago Architecture Biennial, the models have a uniform 1:500 scale. The ones selected for this exhibition by SOM structural engineer Bill Baker represent only the buildings that are either all reinforced concrete or composite systems that are principally concrete.

Since most of the towers are clad in a glazed curtain wall, their structural systems are not apparent on the exterior. This is evidenced by the models of Jin Mao Tower, Tower Palace III, Greenland Jinmao International Financial Center, Shum Yip Upperhills, and aSpire. However, the three models of "tube" structures (DeWitt-Chestnut, Onterie Centre, and Guiyang WTC) illustrate how the facade is a bearing wall in that structural system.

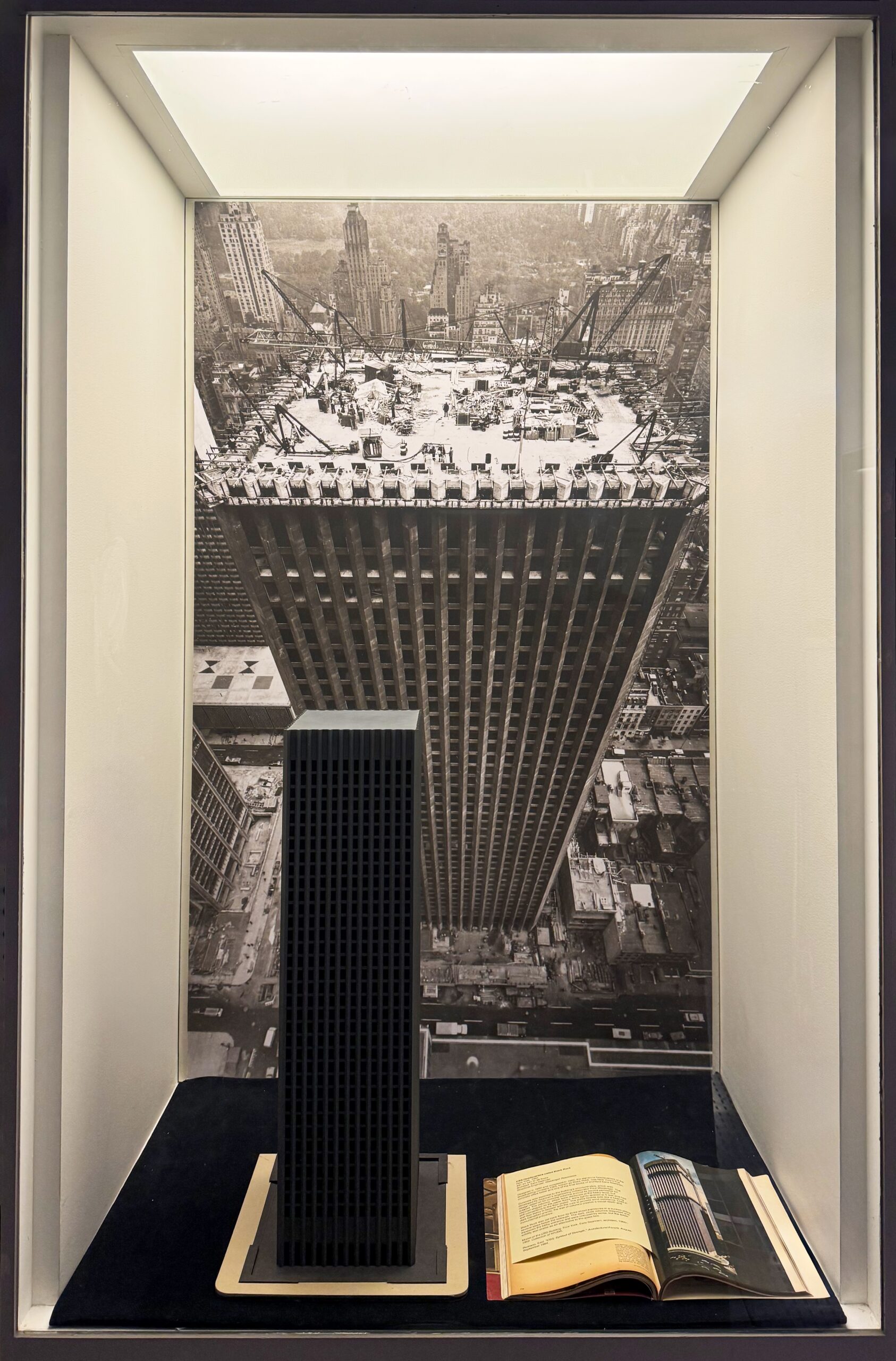

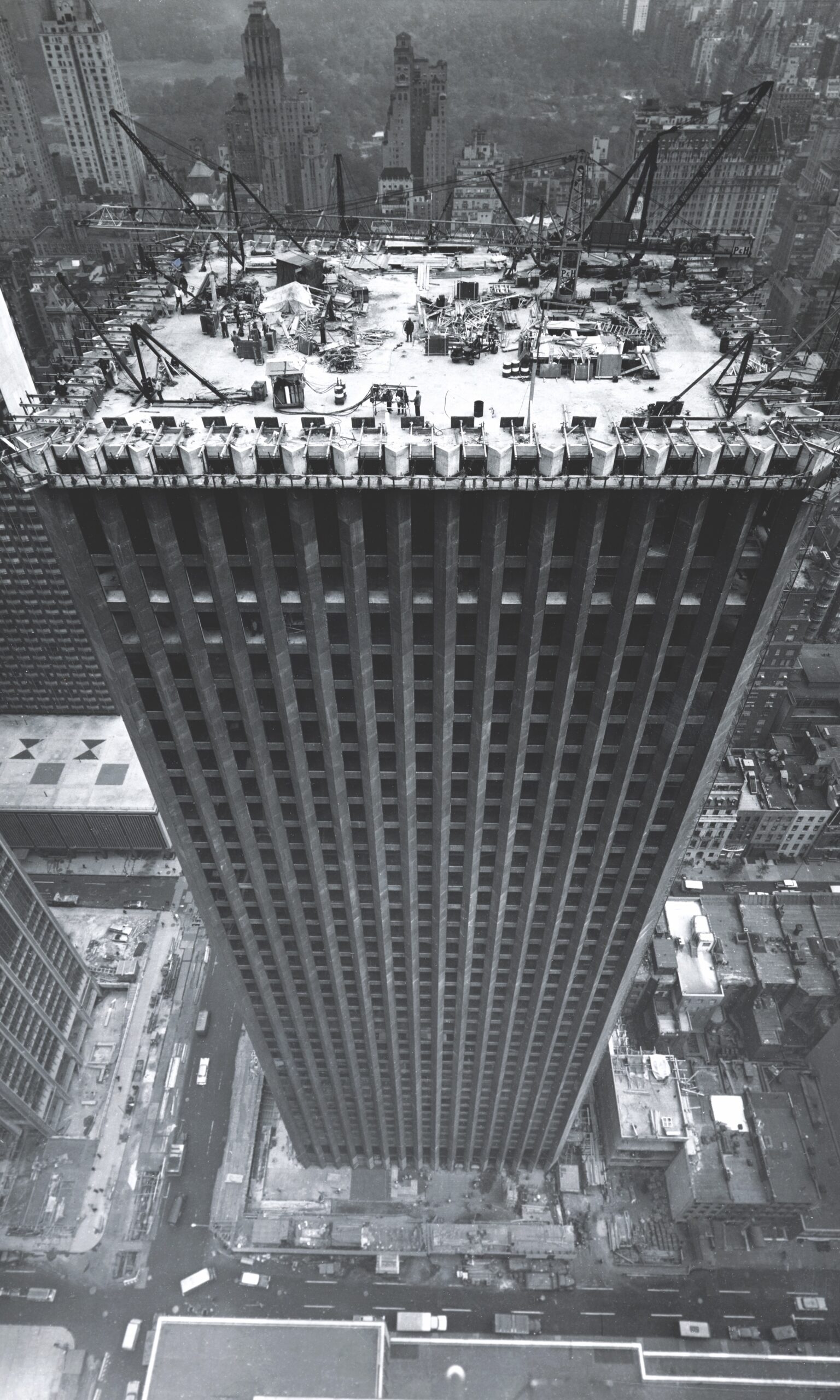

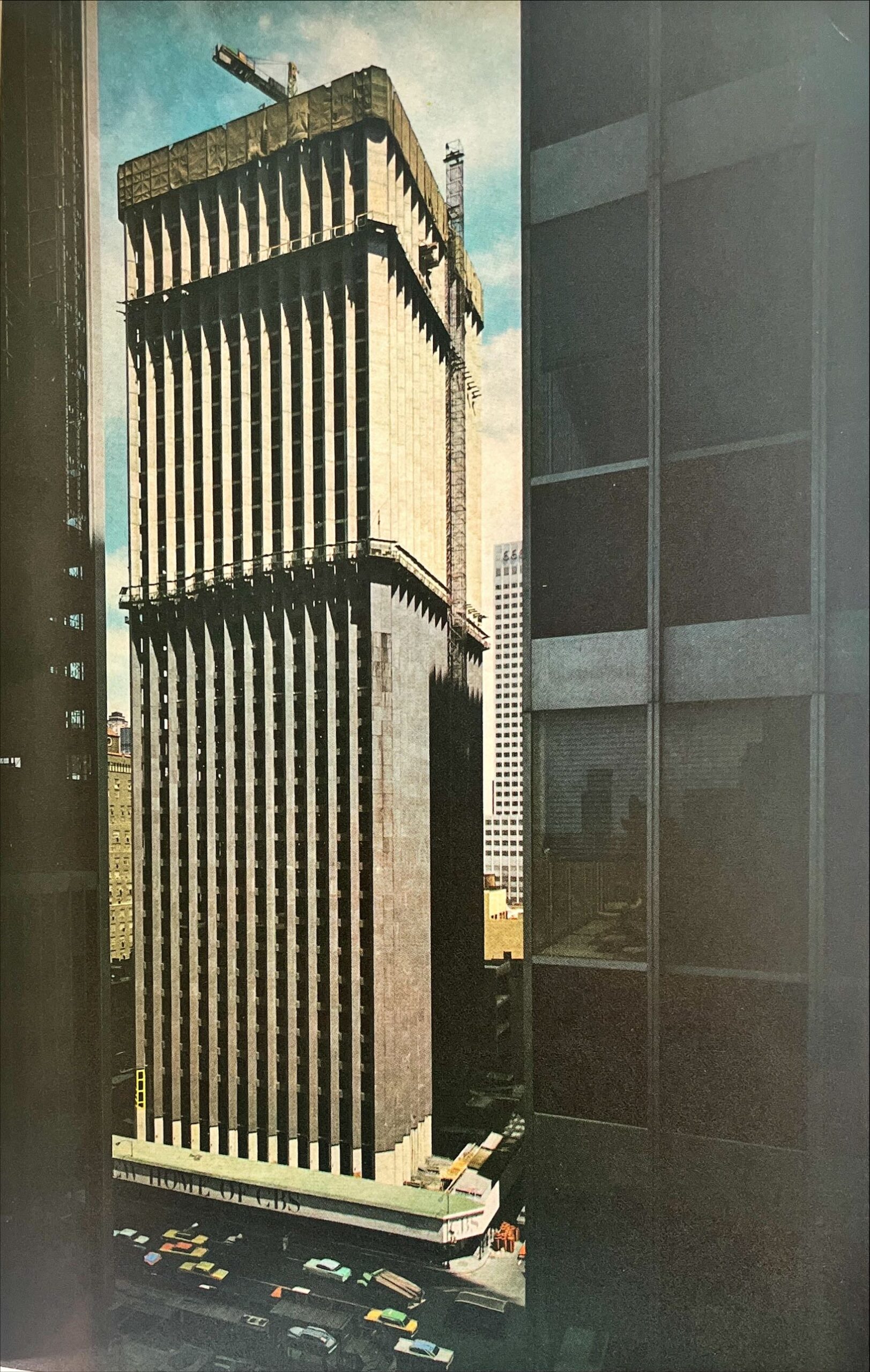

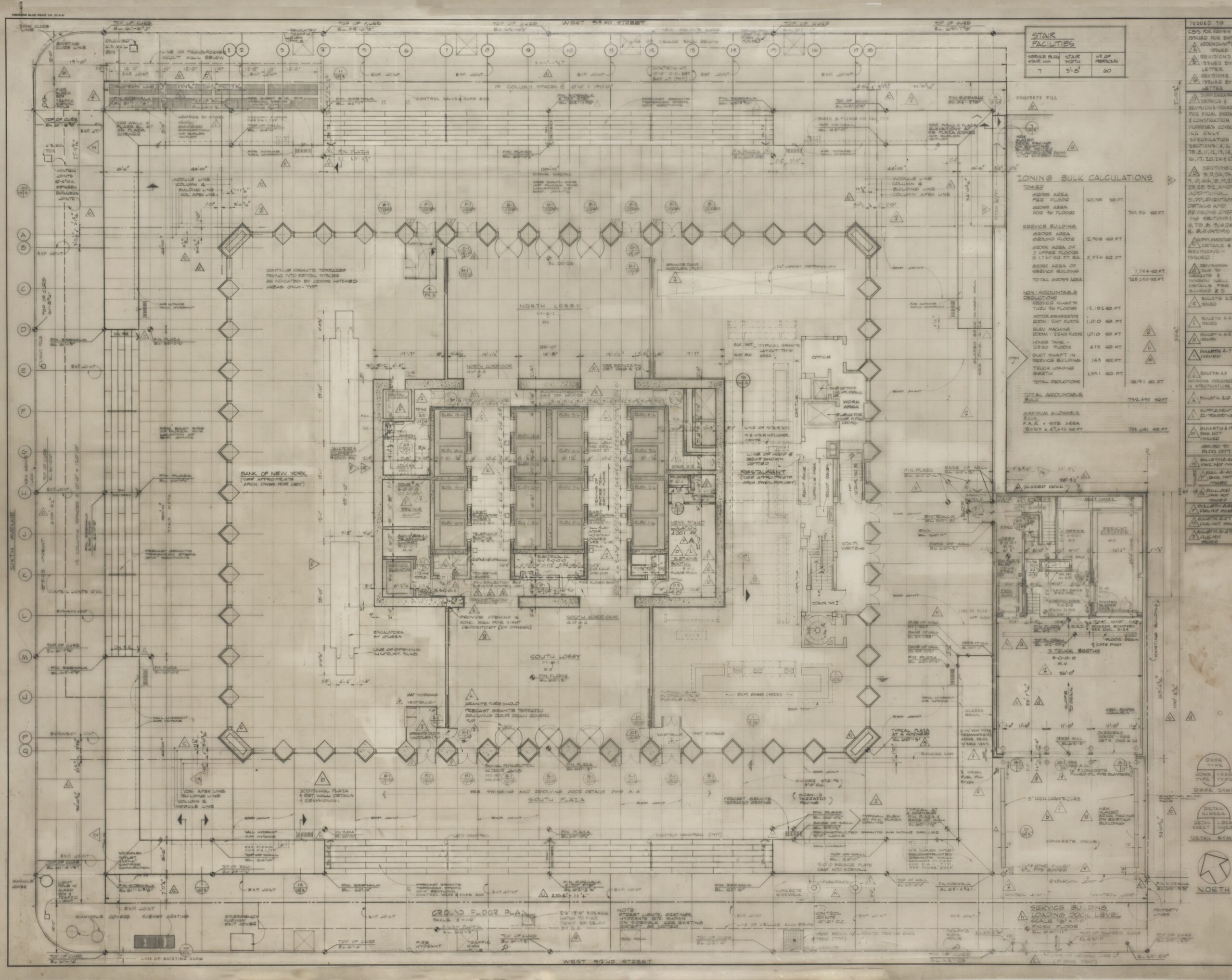

CBS Headquarters, New York, 1965

Architect: Eero Saarinen

Structural Engineer: Weidlinger Associates

CBS Headquarters, "Black Rock"

Designed in 1960 and completed in 1965, the signature headquarters of the broadcasting company CBS, known as Black Rock, was New York's first concrete office tower and one of the final works of architect Eero Saarinen.

Concrete was essential to the building’s structural idea, which was developed by Saarinen's engineering collaborator Paul Weidlinger. The design relied on 52 concrete columns around its square perimeter for support. The columns, which were diamonds at the lobby level, but chevron-shaped on the upper floors, were tightly spaced at 5 feet and had stiff connections to the floor plates. The entire facade acts like a bearing wall that works in tandem with the core to provide wind resistance. Clad in dark Canadian granite, the wall of columns creates a visual depth and monumental presence.

Black Rock was set back from its three street exposures in a sunken plaza several steps below the sidewalk. The dark, close columns disguised and squeezed the lobby entrance and were criticized by some, but the sober solidity won praise as an alternative to the glass box.

To see a lecture by structural engineer Matthys Levy on his work on the CBS Building, click here.

Model of the CBS Building, New York, Eero Saarinen, architect, 1960–1962. Collection of KRJDA.

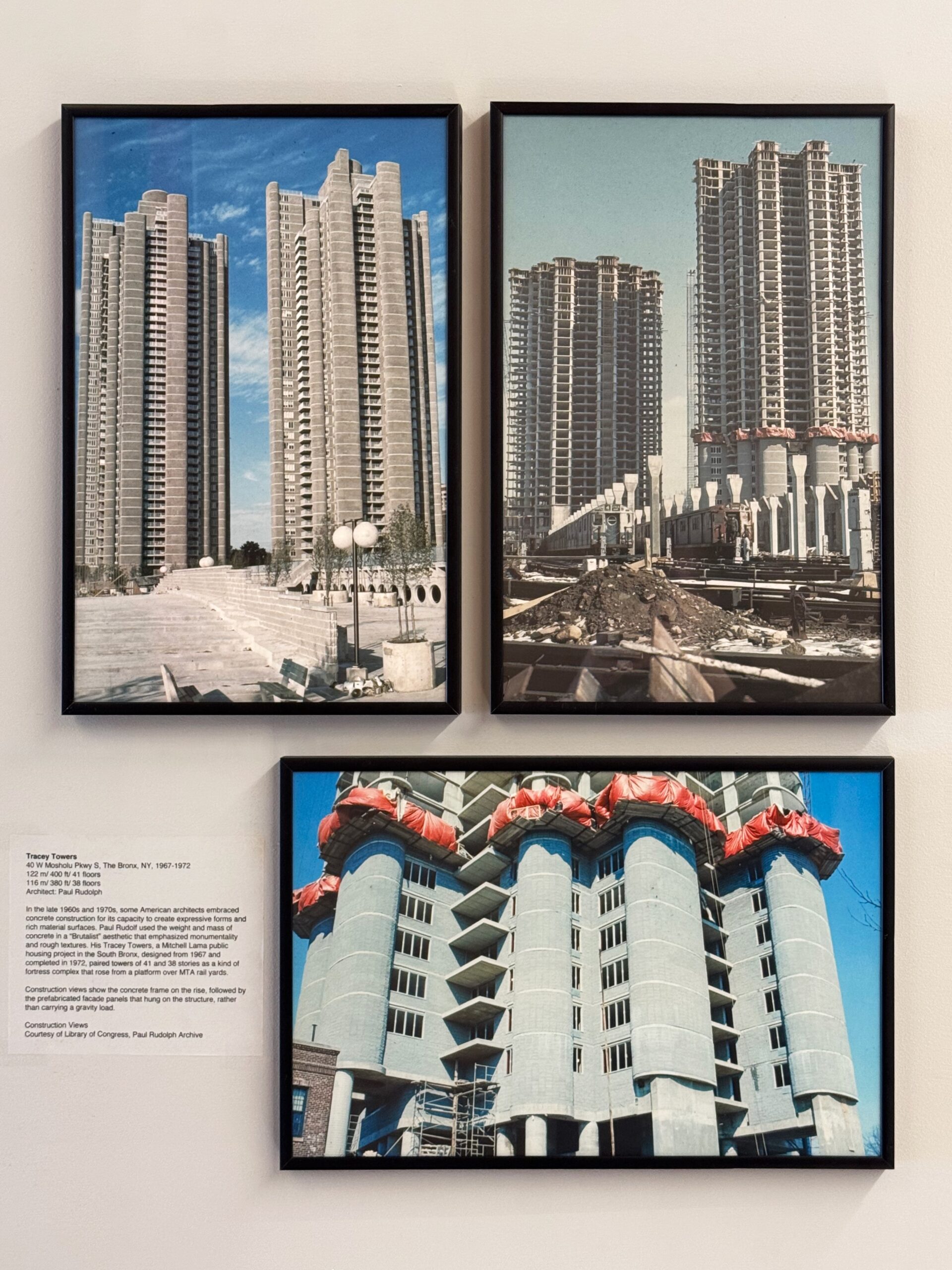

Tracey Towers, 40 W Mosholu Pkwy S, The Bronx, 1967-1972

122 m/ 400 ft/ 41 floors

116 m/ 380 ft/ 38 floors

Architect: Paul Rudolph

Westin Peachtree, Atlanta, 1976

220 m/ 723 ft/ 73 floors

Architect: John Portman & Associates

Marriott Marquis, Atlanta, 1985

169 m/ 554 ft/ 52 floors

Architect: John Portman & Associates

Brutalism: Paul Rudolph and Tracey Towers

In the late 1960s and 1970s, some American architects embraced concrete construction for its capacity to create expressive forms and rich material surfaces. Paul Rudolf used the weight and mass of concrete in a “Brutalist” aesthetic that emphasized monumentality and rough textures. His Tracey Towers, a Mitchell Lama public housing project in the South Bronx, designed from 1967 and completed in 1972, paired towers of 41 and 38 stories as a kind of fortress complex that rose from a platform over MTA rail yards.

Construction views show the concrete frame on the rise, followed by the prefabricated facade panels that hung on the structure, rather than carrying a gravity load.

Formalism and John Portman, Jr.

From the 1960s, the architect and developer John Portman, Jr. began to reshape downtown Atlanta, his hometown with massive high-rises that included trade centers, hotels, and office buildings. His architectural forms were especially dramatic on their interiors, where colossal columns, balconies, and soaring atriums exploited concrete's ability to create monumental and flowing spaces. Portman's Westin Peachtree Hotel, a 73-story cylinder clad in reflective glass, relied on a stiff concrete structural system and was the tallest hotel in the world when it opened in 1976. A decade later, the Marriott Marquis in Atlanta was made of thin ribs of exposed cast-in-place and precast concrete that also divided individual balconies. Subtle changes at each floor level were supported by shear walls that slope outward and shape the swelling interior void that rose to 470 feet, the largest in the world on completion in 1985.

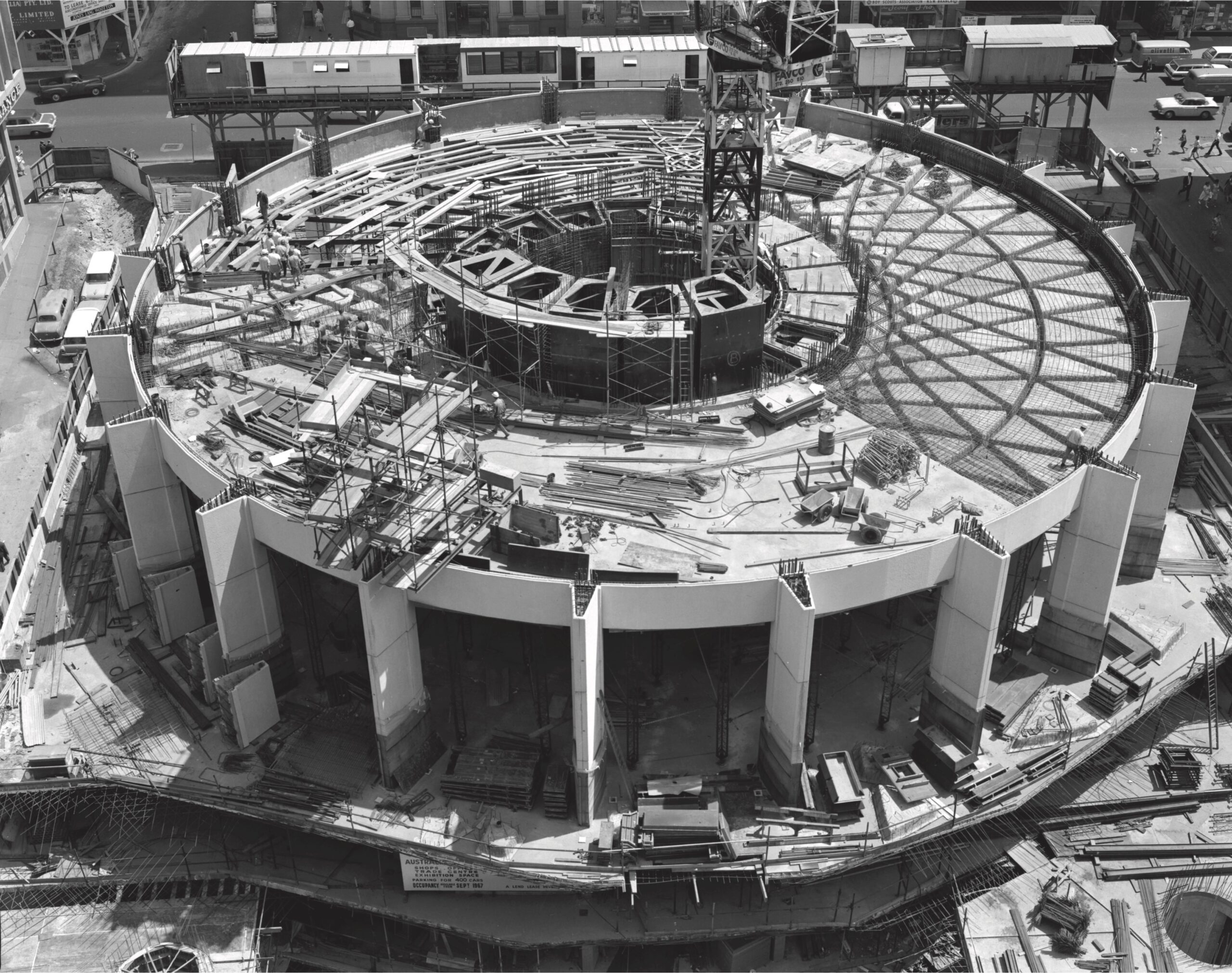

Place Victoria, April 1966

Architect: Luigi Moretti

Structural Engineer: Pier Luigi Nervi

Photo courtesy of Canadian Architect

Australia Square city view and view from plaza, October 1968

Architect: Harry Seidler & Associates

Structural Engineer: Pier Luigi Nervi

Two photos by Max Dupain

Courtesy of Penelope Seidler

Australia Square Tower under construction, October 1965

Photo by Max Dupain

Courtesy of Lendlease

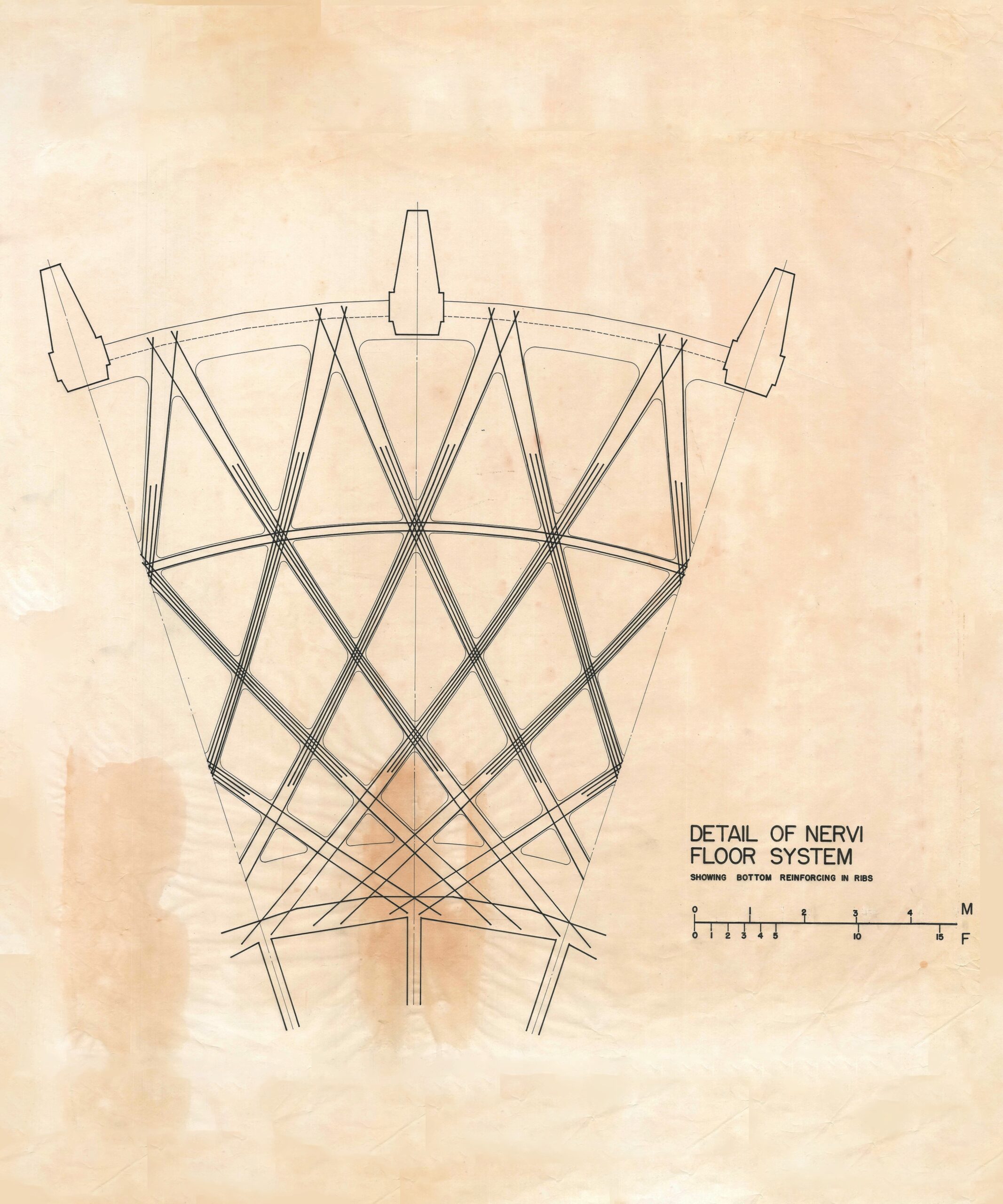

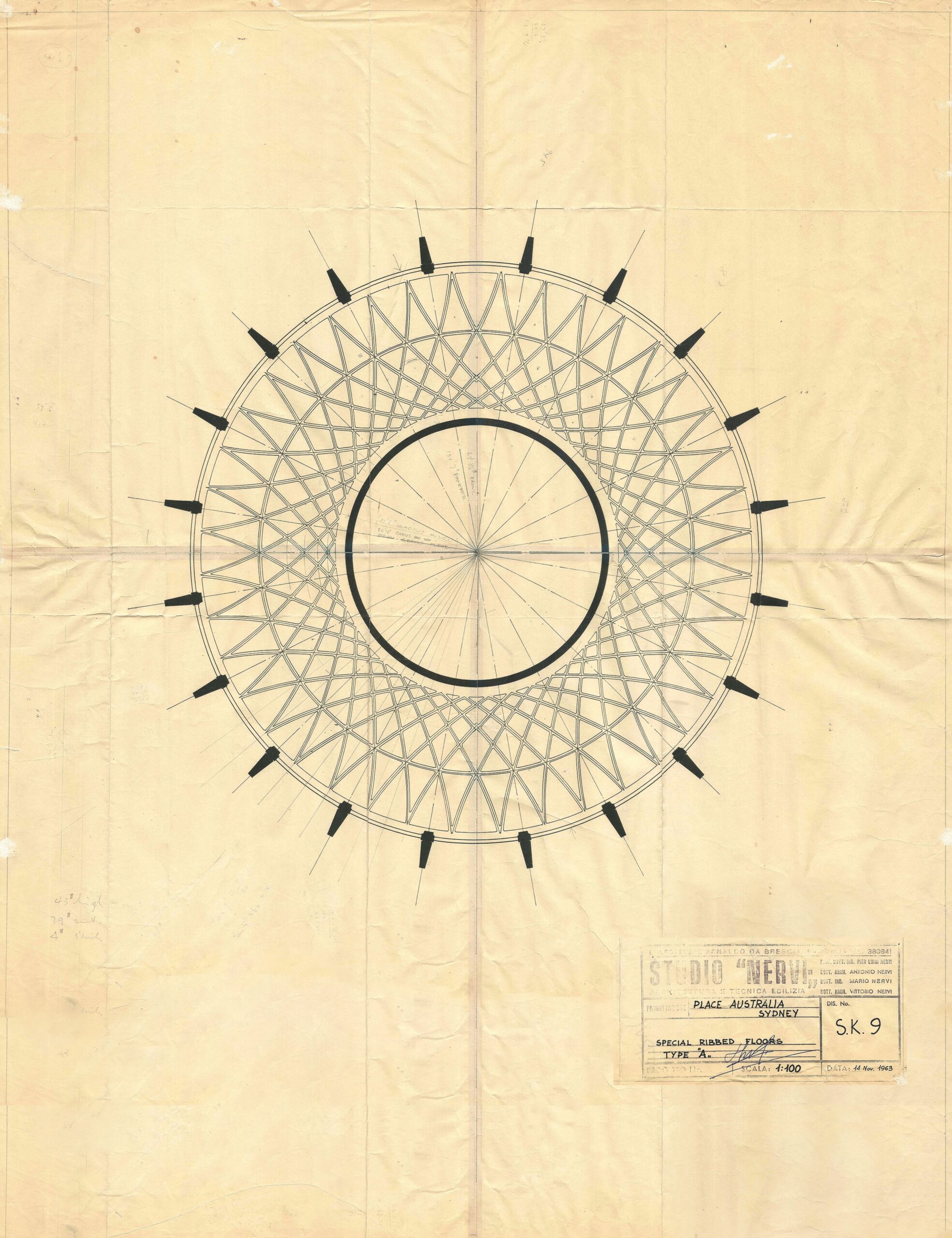

Two drawings of Australia Square Floor Systems by Pier Luigi Nervi

Beyond the U.S.

The International Style, as it applied to American skyscraper design after WWII, can be understood as an aesthetic born in the prewar theory of the architectural avant garde of the 1920s and the Bauhaus diaspora of the 1930s. In other parts of the world where high-rises were embraced in a postwar world, Modernism became a signature style for business buildings.

The brilliant structural engineer Pier Luigi Nervi was responsible for the structural design of several key high-rises in Europe, North America, and Australia, His first, and most famous high-rise the Pirelli Tower (1958) in Milan rose to only 32 stories but symbolized a new era of modern architecture and design in Italy. Nervi believed that architectural expression could spring from engineering principles. In skyscrapers like the Place Victoria (1964) in Montreal and Australia Square (1967) in Sydney, Nervi blended structural efficiency with sculptural forms to create what he termed “structural architecture.”

In Australia Square, architect Harry Seidler designed a 50-story tower that transformed Sydney’s skyline. A simple cylindrical form solved a complex setback problem, opening the neighboring street to light and air. The original structural scheme designed by Civil & Civic (Lendlease’s predecessor) that relied on deep perimeter connections struck Seidler as overly heavy, so in 1963, he contacted Nervi to collaborate.

Nervi suggested a stiffer core to handle wind loads, thereby leaving the perimeter columns to carry only gravity loads. This allowed thinner columns on the building’s exterior. The engineer went further, developing precast formwork so the columns could taper as they rose, stretching the building visually. The formwork was left in place as elements of the building’s cladding.

Nervi also consulted with Seidler on the tower’s lobby ceiling, an array of intersecting spiral ribs similar to those supporting the engineer’s domed arena for the 1960 Rome Olympics. Composed of molded, lightweight ferrocemento pans, the ribs emphasize the building’s circular rhythm while illustrating the flow of forces within the slab above.

Learn more about Seidler and Australia Square in a Museum lecture by author and Curator Vladimir Belogolovsky. Katie Filek, an architectural historian, talked about the Place Victoria in another Museum lecture.

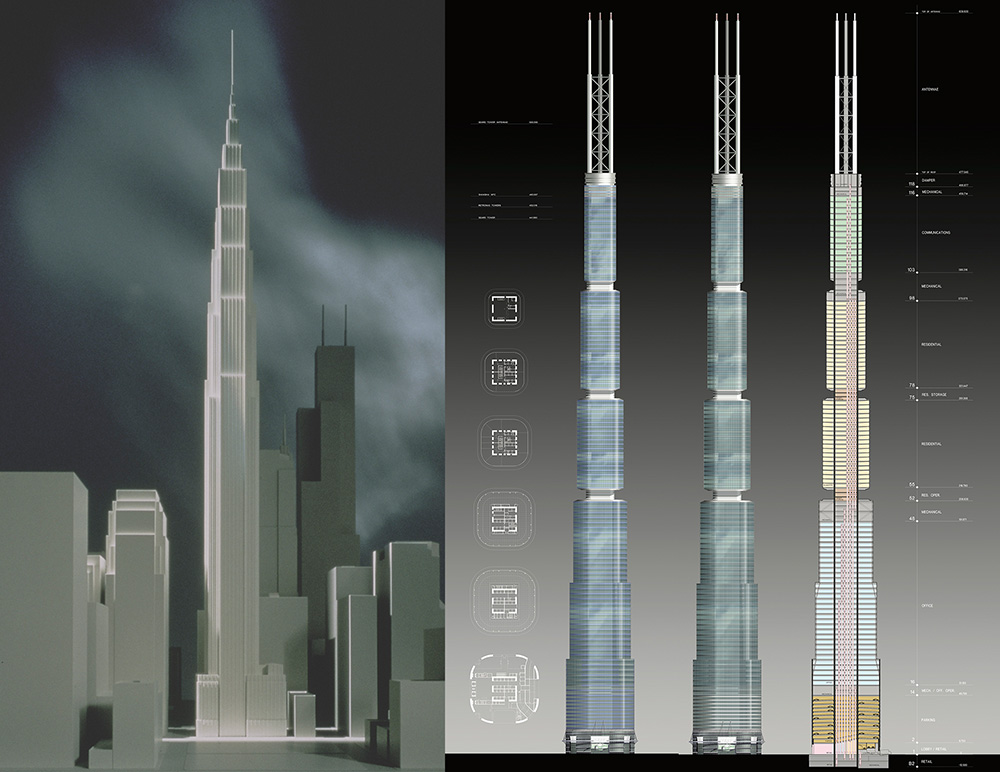

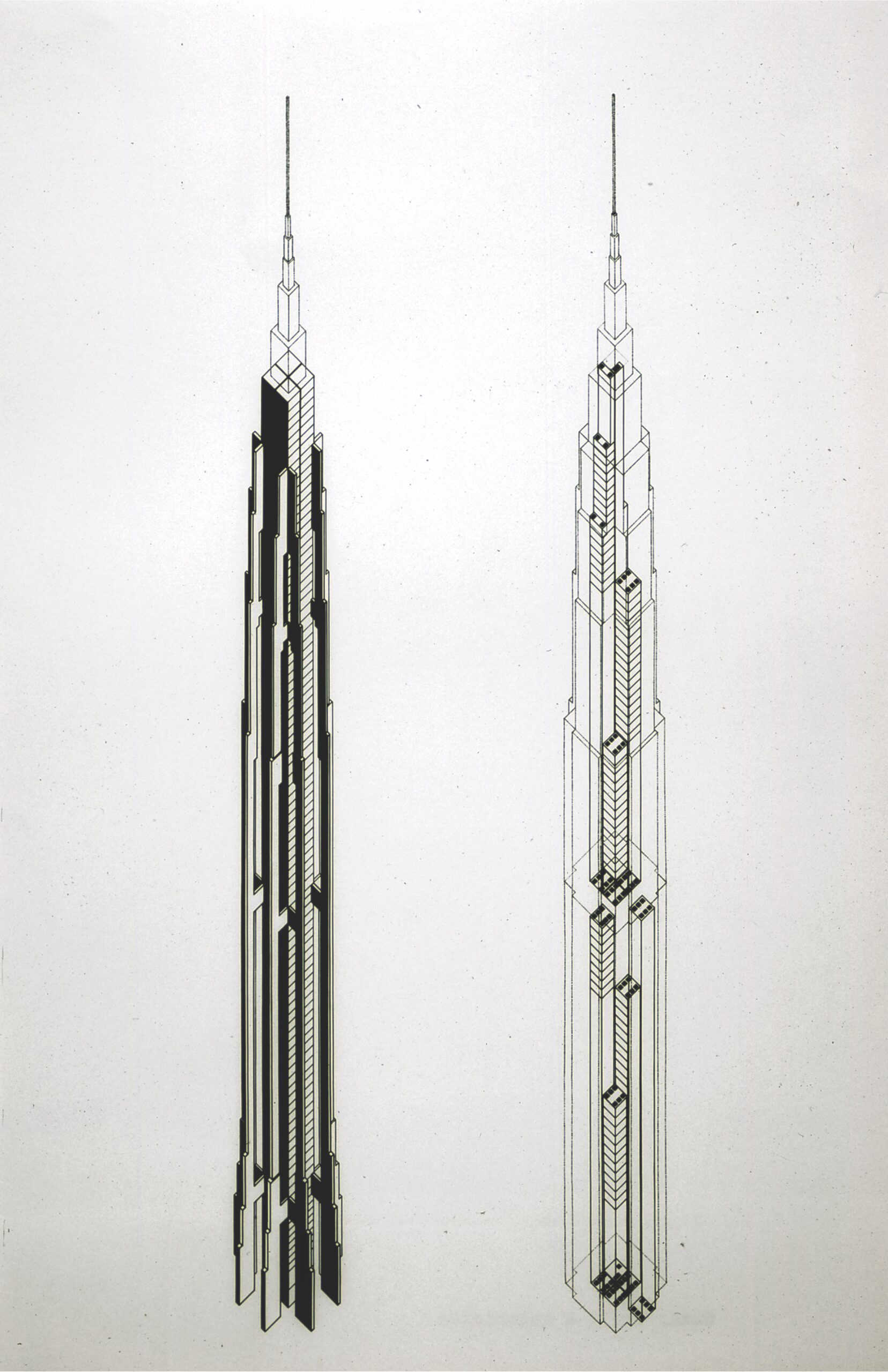

Miglin-Beitler Skyneedle, Chicago, designed 1988

610 m/ 2,000 ft/ 125 floors

Developer: The Beitler Company

Architect: Pelli Clarke & Partners

Structural Engineer: Thornton Tomasetti

7 South Dearborn, Chicago, designed 1999

610 m/ 2,000 ft/ 112 floors

Developer: European-American Realty

Architect & Structural Engineer: Skidmore, Owings & Merrill

Concrete Supertalls

In the 1980s and 90s, as more skyscrapers stretched taller, concrete was widely embraced as a material of stiffness, strength, and economy. Engineering research and advances in construction methods and material mixes also facilitated new heights. From 1988, several proposals for record-breaking, 2,000-foot towers in Chicago pushed engineering ideas even higher.

The earliest was the Miglin-Beitler Skyneedle, designed by Cesar Pelli and structural engineer Thornton Tomasetti as a slender, 125-story telescoping spire. The structural concept relied on a dense concrete core to brace eight mega-columns. The original 11-foot model of the project is on display here, along with a photograph of the context model with other skyscrapers of the Loop and a diagrammatic drawing of the structural system.

In 1999, architects and engineers at SOM designed a slender, 112-story mixed-use office and apartment tower, 7 South Dearborn, that stretched to 2,000 feet with its antenna crest. The structure was conceived as a reinforced concrete core and stayed mast, with the residential floors cantilevered from the core on the upper-levels. The tapering shaft was pinched in at intervals, creating gaps between sections that also served to “confuse the wind” and minimize resonant rocking.

Although these Chicago projects did not come to fruition, the design research and thinking were applied on projects abroad by the same architects and engineers, including in the Petronas Towers in Kuala Lumpur and the Burj Khalifa.

Petronas Towers, Kuala Lumpur, 1998

452 m/ 1,483 ft/ 88 floors

Architect: César Pelli

Structural Engineer: Thornton Tomasetti

The construction photographs on the screen were taken mainly on numerous site visits by the architects from Pelli Clarke & Partners (formerly Cesar Pelli & Associates), who shared this series with the Museum. The selection focuses on the role of concrete in the foundations and structural system.

Petronas Towers

In the 1990s, the race for record-breaking skyscraper height moved beyond the U.S. to Southeast Asia, China, and the Middle East, most often using the expertise of American architects and engineers. Rapid urbanization in these countries led by government initiatives fueled the ambition to make a towering statement to the world.

The first buildings beyond the U.S. to strategically use height to attract global attention were the Petronas Twin Towers in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Petronas, the state-owned oil and gas company, planned a modern headquarters as part of the urban development of a new city center, called KLCC. Petronas invited international teams, mostly American, to compete for the commission. They selected Cesar Pelli and structural engineers Thornton Tomasetti – who again collaborated, as they had for the Miglin-Beitler Skyneedle – to design a pair of slender spires that were bridged at the center to form a symbolic “gateway to the East.”

Although the winning scheme did not initially propose record-breaking height, that ambition emerged as the project took shape. As completed in 1998, the Petronas Twin Towers reached 1,483 ft./ 452 m. to the tips of their pinnacles – a vertical height that slightly surpassed the flat roof of Chicago’s Sears Tower to steal the title of world’s tallest building from the U.S. for the first time.

The twin buildings’ floor plan is an 8-pointed star, a reference to Islamic geometric patterns, with circles and triangles that project from the main space to capture views. The structural scheme relies on a central core and a ring of 16 robust concrete perimeter columns, as well as a series of outrigger floors. The primary construction material was concrete because the government required that materials be sourced in Malaysia, which had no national steel industry.

Architect Fred Clarke talked about the firm's work on the Petronas Towers in a lecture for the Museum as part of the WORLD VIEW lecture series about global supertalls. Watch the lecture here.

Model of the Petronas Towers by Ken Champlin, courtesy of Pelli Calrke & Partners

Burj Khalifa, Dubai, 2010

828 m/ 2,717 ft/ 163 floors

Developer: Emaar Properties

Architect: & Structural Engineer Skidmore, Owings & Merrill

Jeddah Tower, Jeddah, construction started 2013

1,000+ m/ 3,281+ ft/ 167 floors

Developer: Jeddah Eonomic Company

Architect: Adrian Smith + Gordon Gill

Structural Engineer: Thornton Tomasetti

BURJ KHALIFA & JEDDAH TOWER

The models in this case illustrate the structural designs for the world’s tallest buildings: the current title-holder, the Burj Khalifa at 828 m./ 2,717 ft., and Jeddah Tower, which is projected to rise to 1,000+ meters. Burj Khalifa was conceived in 2005 and completed in 2010. Jeddah Tower began construction in 2013, but was paused in 2018 at about one quarter of its final height: it has recently resumed construction.

Unlike the tallest towers of the 20th century, which relied on steel frames and point-support columns, Burj Khalifa and Jeddah Tower carry their gravity and lateral loads on a system of thick, reinforced-concrete walls. Their “liquid stone” is a sophisticated mix of high-strength concrete that for Burj Khalifa was pumped to an unprecedented height of 600 m.

Both buildings employ a tapered, “buttressed core” structural system with three wings in a Y-shaped plan. Jeddah Tower, however, is all walls, so a solid, slightly slanting plane ends each wing, rather than supporting columns.

The Burj Khalifa model was made by SOM architects to illustrate the structural system and shows the reinforced concrete core, cross walls, floor slabs, and the few columns near the slab edges. Above level 156, for constructability, the structure changes to a steel braced frame. For the occupied floors, though, high-performance concrete was preferred for its mass, stiffness, and, as a liquid, for its moldability and pumping ability. In addition, it insulates sound between floors, which is an advantage in residential buildings.

The Jeddah Tower, a 3D-printed structural model made by the structural engineer Thornton Tomasetti, shows the lower floors of the building. As the engineers explain: “the structural form of the tower utilizes a bearing wall system in its purest form: all vertical concrete elements are arranged to resist both gravity and lateral loads, with no columns or outriggers.”

Learn more about the development of the buttressed core system in a lecture for the Museum by engineer Bill Baker. Robert Sinn, structural engineer at Thornton Tomasetti, presented a lecture about the Jeddah Tower.

Burj Khalifa model is on loan from SOM. The Jeddah Tower bearing wall system model was 3D printed for the Museum by Thornton Tomasetti.

Burj Khalifa, Dubai, 2010

828 m/ 2,717 ft/ 163 floors

Developer: Emaar Properties

Architect & Structural Engineer: Skidmore, Owings & Merrill

BURJ KHALIFA WIND-TUNNEL MODEL

In 2010, after five years in design and construction, the Burj Khalifa in Dubai in the United Arab Emirates opened at a stunning 2,717 feet/828 meters and today remains the world’s tallest building. This wind tunnel model of the tower illustrates an important part of that process.

The developer of the Burj Dubai, Emaar, like the ruling family and government of the emirate, sought to attract worldwide attention with large-scale, eye-catching building projects. In 2005 Emaar approached several architectural forms to compete for a commission for the next world’s tallest building. Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM) won with a design led by Adrian Smith and structural engineer William F. Baker. The form was a slender tower with three wings that tapered and spiraled as it rose to a height of 523 meters – just barely taller than the then record-holder Taipei 101 in Taiwan.

As the SOM team developed the design, it stretched substantially. As Bill Baker has stated the tower was “virtually designed in the wind tunnel.” Iterative tests at RWDI with a series of models showed how adjustments to the tower’s shape and details, including a reversal in the direction of the stepped spiral to the prevailing wind, could help “confuse the wind.” Thus, integrating wind-engineering principles allowed the tower to grow an astonishing 300 meters in height. Together, the innovative “buttressed core” structural system (described in a case at the other end of the gallery) and discoveries in the wind tunnel made possible a leap in vertical height that far outpaced any in history.

Aeroelastic wind tunnel model, 1:500 scale, on loan from RWDI

Several types of wind-tunnel models were used to test different conditions. The engineers at RWDI explained: "As the design progressed, we conducted an extensive program of wind tunnel testing at our Guelph, Ontario facility, using mostly 1:500 scale models. The test regimen included rigid-model force balance tests, full multi-degree-of-freedom aeroelastic model studies, measurements of localized pressures, and pedestrian wind environment studies." The aeroelastic model shown in this case was used to simulate the complex interactions between aerodynamic forces and structural flexibility in order to understand and mitigate wind-induced vibrations.

One Thousand Museum, Miami, 2019

213 m/ 699 ft/ 60 floors

Developer: Zaha Hadid Architects

Structural Engineer: DeSimone Consulting Engineering

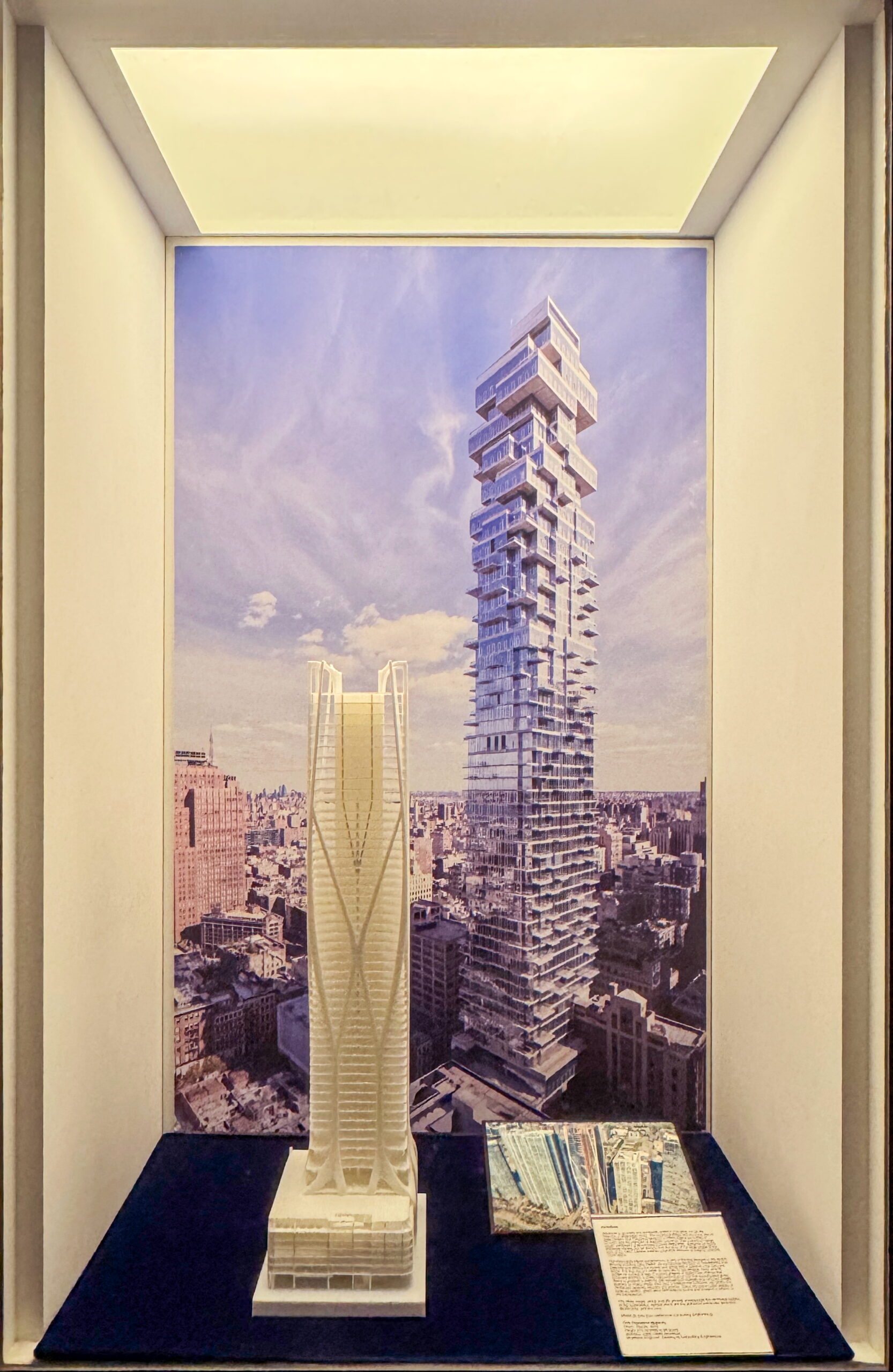

56 Leonard, New York, 2016

243 m/ 796 ft/ 60 floors

Developer: Alexico Group and Gerald D. Hines Interest

Architect: Herzog & de Meuron Architekten

Formalism: One Thousand Museum and 56 Leonard

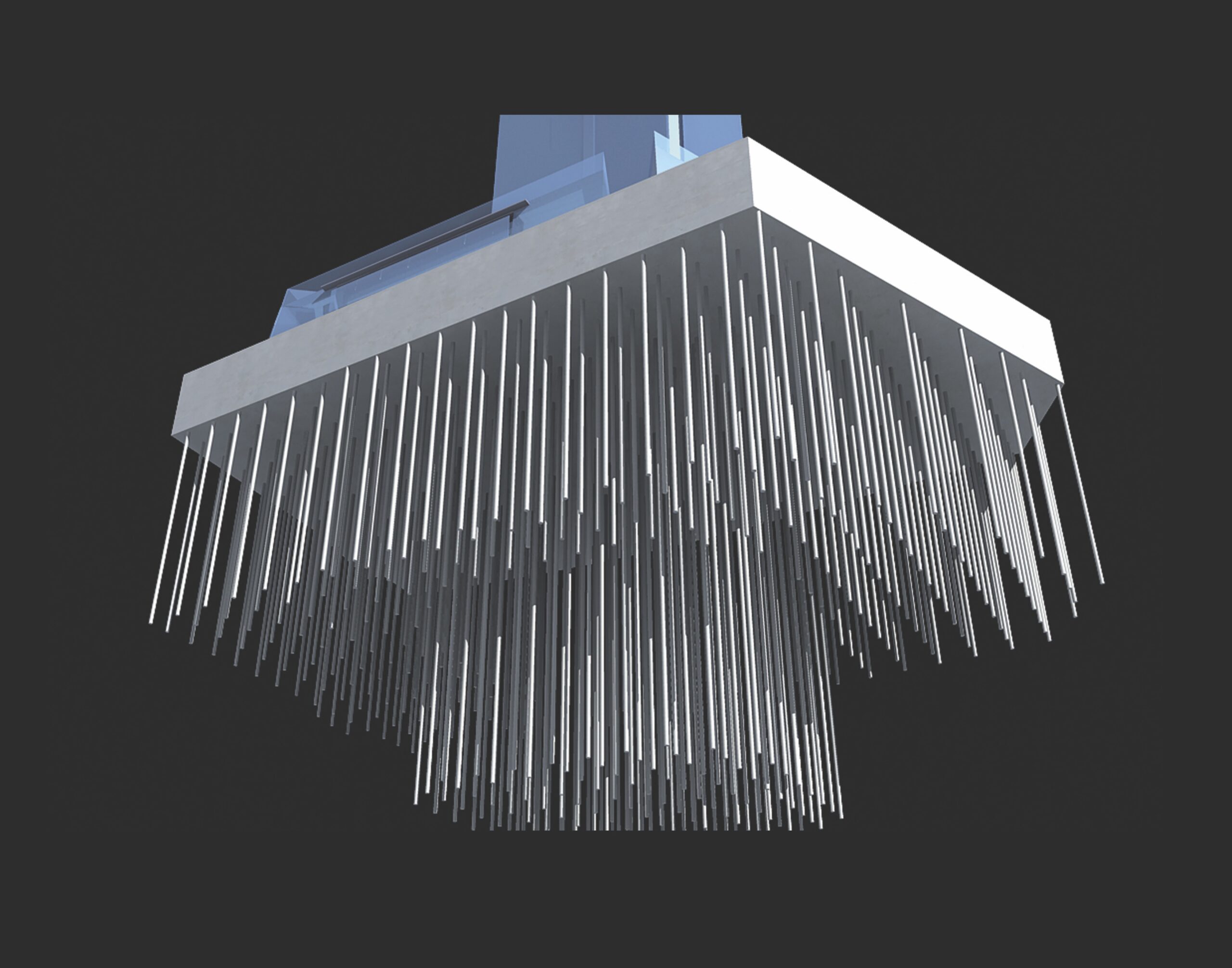

Advances in concrete and composite systems now allow for infinite invention in skyscraper forms. The sculptural shape and the curvy ribs of Zaha Hadid’s One Thousand Museum in Miami exploit the fluidity of concrete and the precision of bespoke formwork. The precarious “jenga tower” cantilevers at 56 Leonard in lower Manhattan, designed by Swiss architects Herzog and de Meuron that are seen in the large image at the back of the case, express another surprising attribute of weighty concrete construction.

The ultra-luxury Miami condominium is one of the last designs of the award-winning architect Zaha Hadid’. Its curvaceous ribs form an exoskeleton that supports and stiffens the facade and along with a massive core carry the floors. The thin ribs are made of concrete in two senses. Their smooth sculptural surface is cast in custom shapes of Glass Fiber Reinforced Concrete (GFRC), a costly high-performance mix that incorporates glass fibers to produce a material with exceptional strength and reduced weight. Erected as empty shells, they also constitute the formwork into which the reinforced concrete columns are poured. There are some 5,000 pieces of bespoke GFRC, which were fabricated in Dubai and shipped to Miami, in the exoskeleton.

The white model, which was 3D printed, emphasizes the structural system of the exoskeleton, behind which are the sheltered balconies, enclosed apartments, and the core.

Model on loan from DeSimone Consulting Engineering.

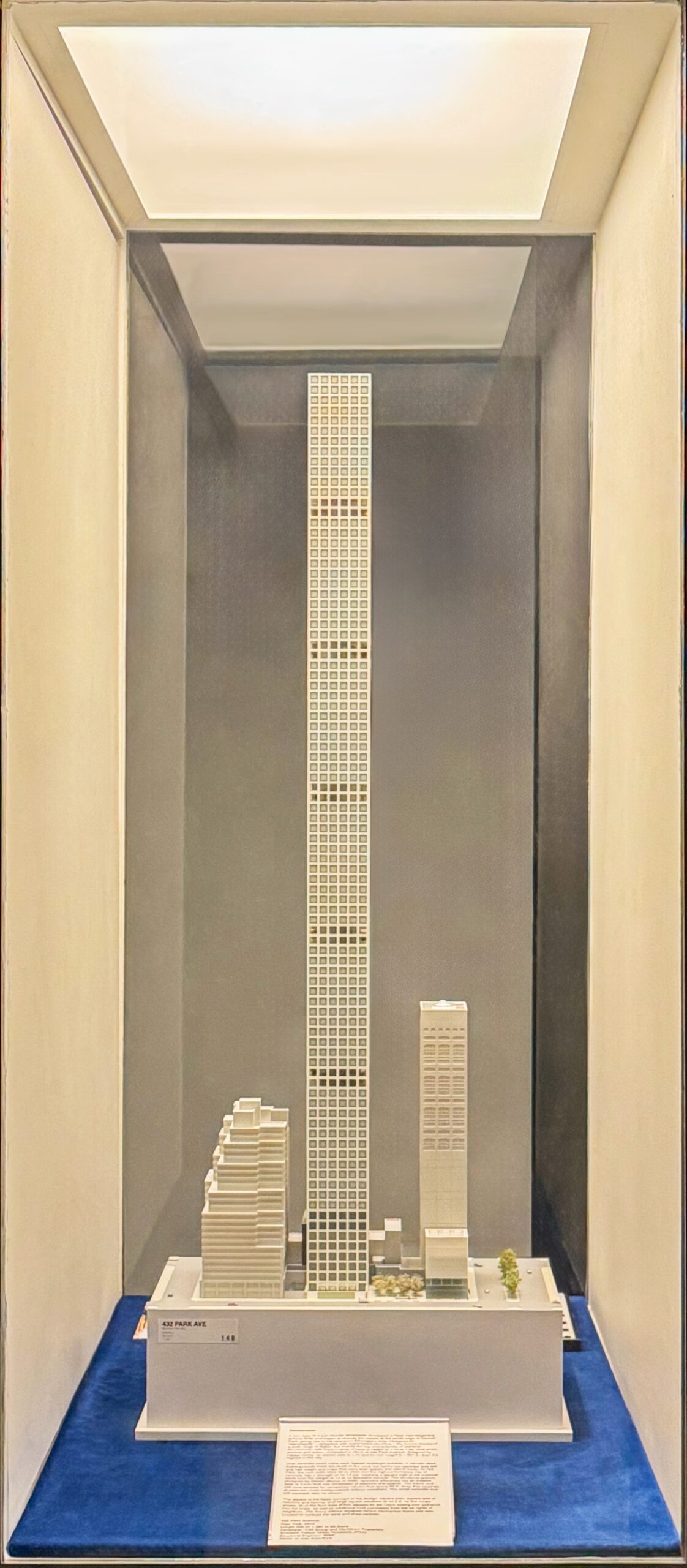

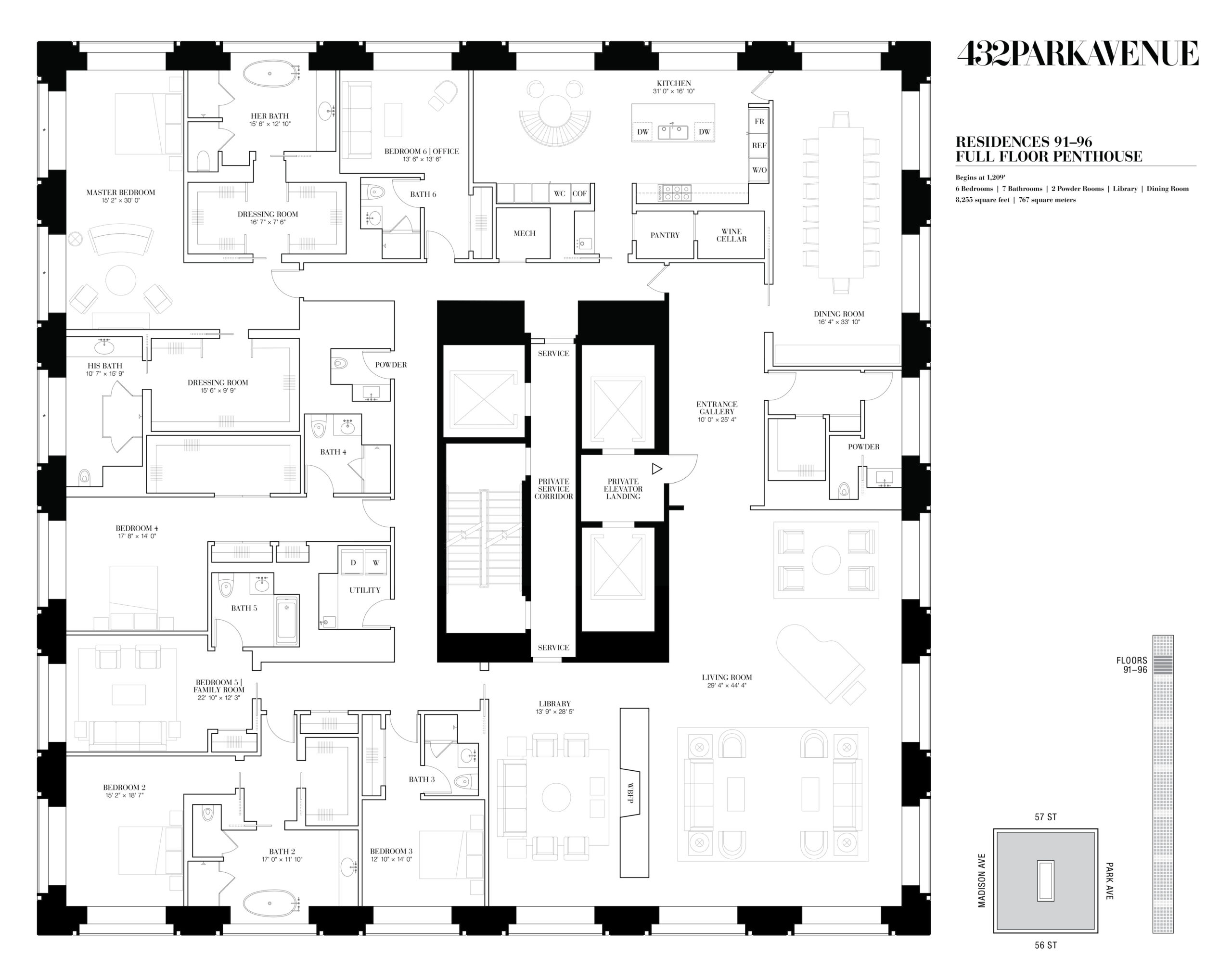

432 Park Avenue, New York, 2014

426 m/ 1,397 ft/ 85 floors

Developer: CIM Group and Macklowe Properties

Architect: Rafael Viñoly Architects (RVA)

Structural Engineer: WSP

Slenderness

A new type of super-slender skyscraper developed in New York beginning around 2009 and began to change the skyline at the south edge of Central Park, giving rise to the nickname Billionaire’s Row. Designed by “starchitects” – designers with brand-name identities – the towers displayed a wide range of styles, but shared the key characteristic of extreme slenderness, with aspect ratios of base to height of 1:12 to 1:24. One of the earliest and tallest, completed in 2014, is 432 Park Avenue, designed by Rafael Viñoly. Its aspect ratio is 1:15 and its roof height is 1,397 ft., then the highest in the city.

Only concrete could make such “pencil” buildings possible. A slender steel building would move too much in the wind, but reinforced concrete was stiff and had weight and mass that carry both gravity and lateral loads. At 432 Park, the core walls were 30 in. thick and the high-performance mix of concrete has a strength of 12-14 psi, meaning a square inch of the material could bear the weight of 12 to 14 thousand pounds. The structural system, designed by Silvian Marcus of WSP, operated effectively like an exterior tube or frame that was composed of columns and beams. The frame and stiff core allowed for completely column-free space 30 ft. deep that could be divided into room configurations without constraint. The white concrete was left exposed, with no veneer.

The square is the basic concept of the design: square plan, square grid of columns and beams, and large square windows of 10.5 ft. As the model shows, all of the floor area (FAR) allowed by the City’s zoning was gathered into the tower, as well as additional FAR purchased from the air rights of neighbors. The floors without windows reflect mechanical floors and also function to confuse the wind and shed vortices.

Model on loan from RVA

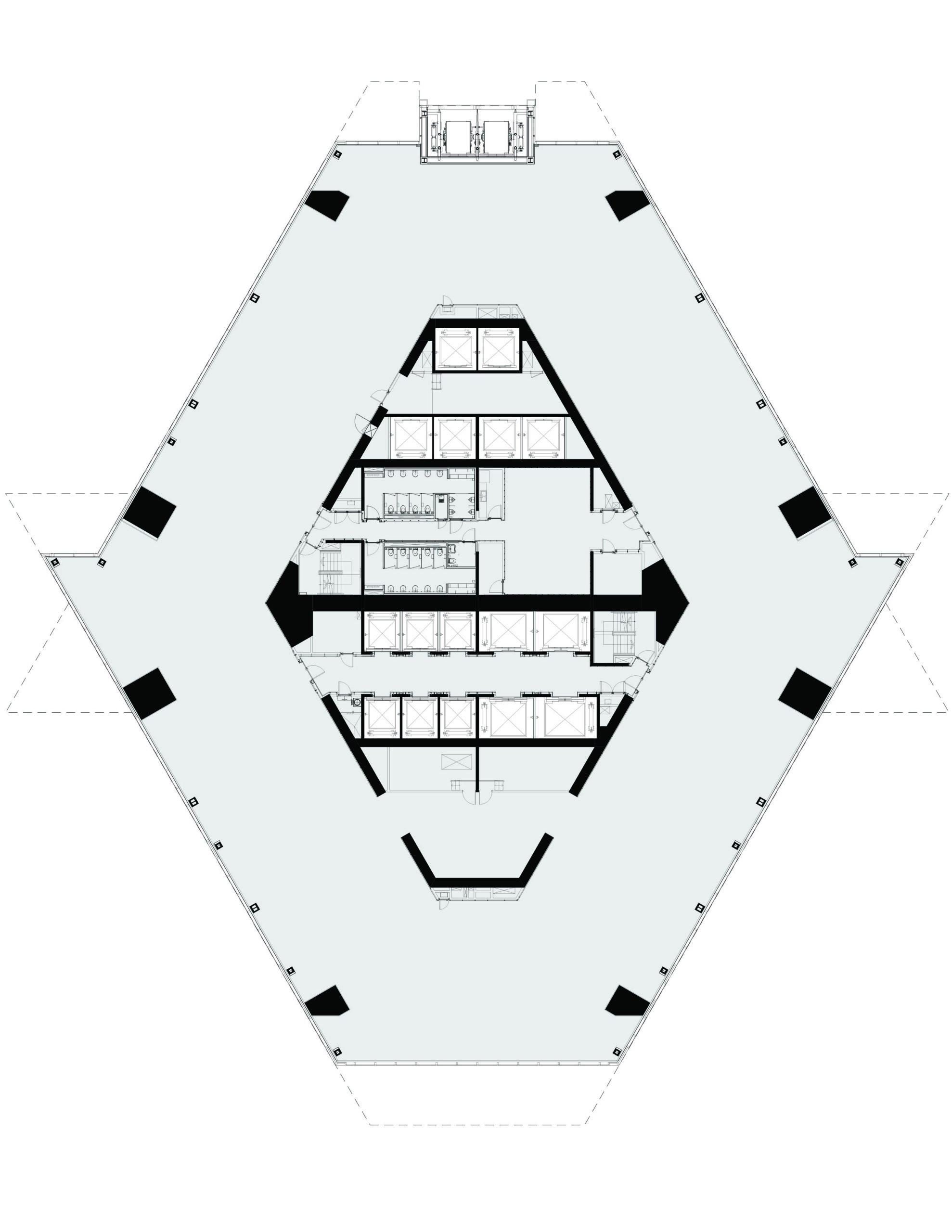

Merdeka 118

679 m/ 2,233 ft/ 118 floors

Developer: Permodalan Nasional Berhad

Developer: Fender Katsalidis

Structural Engineer: LERA & Robert Bird Group

Merdeka 118

Twenty-five years after the Petronas Twin Towers, Merdeka 118 became the tallest skyscraper in Kuala Lumpur and the second tallest building in the world. At 2,233 ft./ 680 m. to the tip of its spire, it was half again taller than Petronas. The tower achieved its height by employing a massive diamond-shaped core of ultra-high-strength concrete and a concrete and steel composite megaframe and outriggers.

Merdeka’s distinctive zig-zag shape and off-center spire makes reference to a human form – the standing silhouette of the country’s leader as he famously raised his arm to the crowd to declare “Merdeka,” meaning independence from colonial rule. The complex pattern of elongated diamonds also relates to traditional Indonesian textiles. The asymmetric form did not perform efficiently to confuse the wind, so the engineers made the central core extra strong and stiff by using a new mix of high-performance concrete that was prepared on the building site.

The red wind-tunnel testing model of Merdeka 118, created by the company RWDI, is the type known as a “pressure tap.” The small metal valves and the inscribed numerical grid are connected to small tubes and a computer that measures surface pressures on the façade. The data is used to develop and design structural loads and cladding. Thus, the building’s curtain wall of faceted blue glass can sheathe the tower and disguise the massive structure of concrete and steel that makes its brittle appearance possible.

The construction photo featured here was taken by Turner International. Click here to watch a lecture from the Museum’s WORLD VIEW series by Ahmad Abdelrazaq from Samsung C & T, the building’s contractor, in which he discusses the structural engineering and construction of Merdeka 118. Learn more about the building from Karl Fender, its architect and cofounder of Fender Katsalidis Architects, in another Museum lecture here.

THE MODERN CONCRETE SKYSCRAPER is supported, in part, by public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs in partnership with the City Council.

THE MODERN CONCRETE SKYSCRAPER is made possible by the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Kathy Hochul and the New York State Legislature.