PRESENT & FUTURE SKYLINE

What will the Manhattan skyline look like in 2023? The section of the exhibition that considered this question was organized on a long central table, covered in an early twentieth century fire insurance map (originally created for the exhibition Ten & Taller), that featured six areas and groups of images, detailed below. On the table was also displayed a wood model of Midtown, created in 2007 by the amateur model maker Michael Chesko.

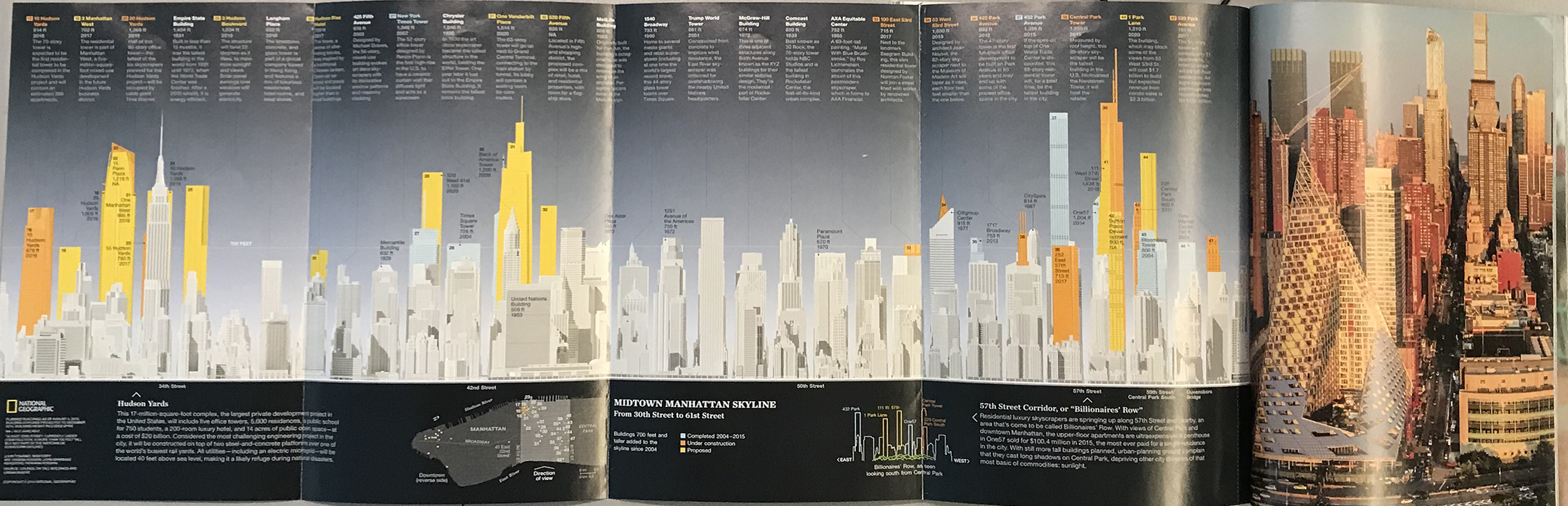

Two overview images offered projections of the future Manhattan skyline. One, which had been created for an issue of National Geographic in December 2015, was presented as an open magazine. Their graphic represented the lower Manhattan skyline in 2020 as seen from Brooklyn and included profiles of all buildings, current and projected.

Top: National Geographic, December 2015. Published in 2015, this detailed elevation of the midtown Manhattan skyline was commissioned by National Geographic to highlight the “unprecedented boom in tall buildings” in New York City since 2004. As the article explained, before 2004, Manhattan had been home to only 28 skyscrapers of 700 feet and taller. Since then, 13 more have been completed, 15 are under construction, and 19 are proposed – 47 in total. Viewed from the East River from the 30th St. to 61st St., the drawing included all completed, under construction, and proposed skyscrapers.

Bottom: Renderings by Ondel Hylton, courtesy of Ondel Hylton and CityRealty.

The other was a digital drawing created in 2016 by Ondel Hylton (above) for the real estate website CityRealty and its related news blog 6sqft.com that added to a Google Earth base image of lower Manhattan all the buildings then under construction or announced development that might be completed by 2020. Compilations such as this are extraordinary, because they require in-depth knowledge of the current real estate market as well as an analysis of zoning issues. They illustrate what architects or developers rarely include in their promotional images – their competitors. Because this image dates from 2016, it includes some projects that have since faltered, while some newer ones are missing. The city is constantly evolving, so a “future” model can never truly be up to date.

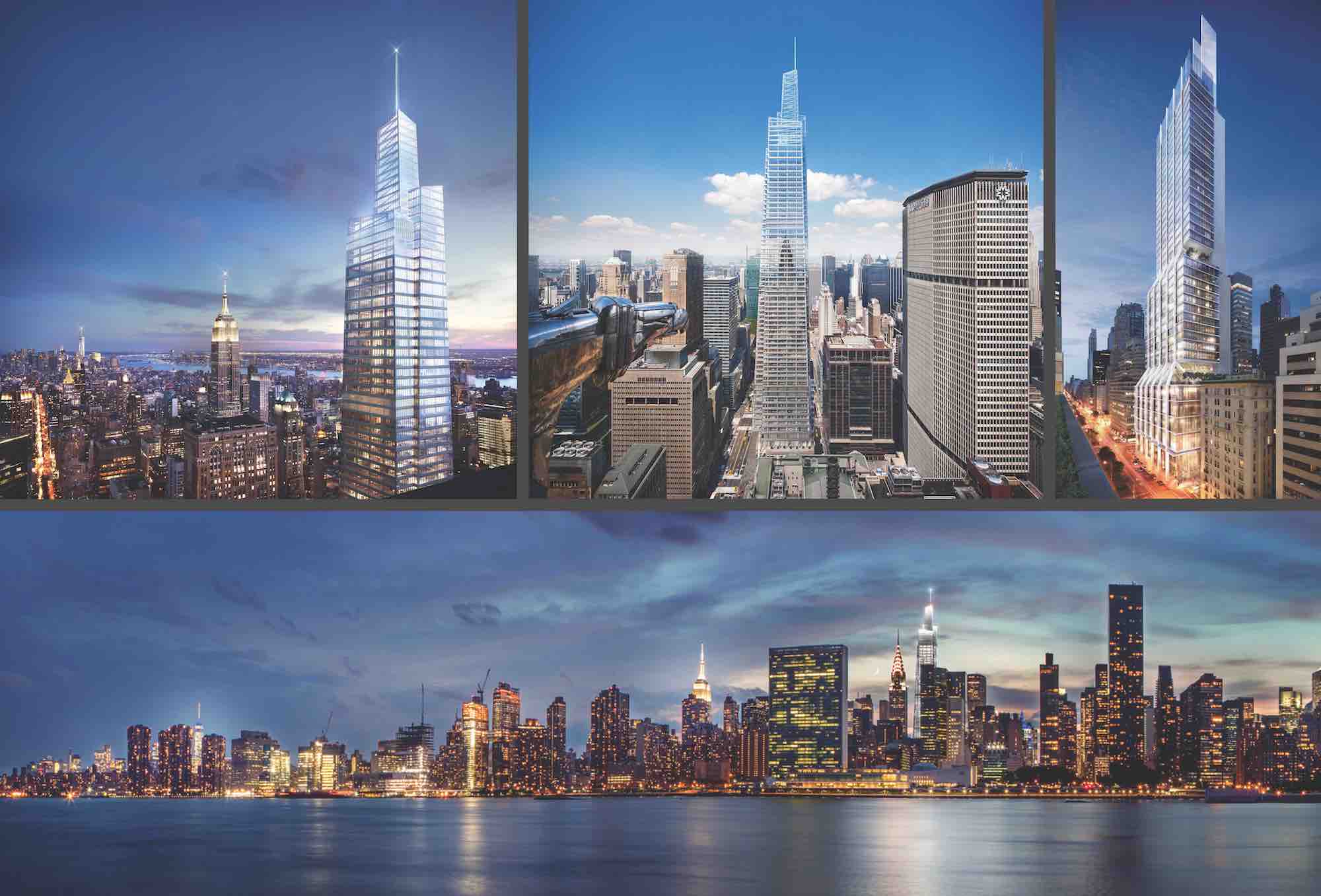

Still, these digital projections clearly reveal the characteristics of a distinctly new era of the Manhattan skyline. They show a multiplicity of new towers that are taller than those of past eras. There are two types. Office buildings or mixed-use structures have large floor plates and greater girth. Residential towers have slimmer proportions: at least twenty supertall and super-slender condominium towers are currently under construction, and many more are projected.

In addition, this overview illustrates several new areas with a concentration of new skyscrapers: the West Side development of Hudson Yards with at least sixteen new towers; the rebuilding at Ground Zero and other sites across lower Manhattan; new high-rise development along the East River, including the Brooklyn and Williamsburg waterfront; and future towers in the area around Grand Central rezoned as East Midtown.

The area around Grand Central, the main terminal for suburban commuter rail lines to Westchester and the Hudson Valley, as well as the hub for five city subway lines, became the anchor for Midtown in the 1920s and, even more so, in the post-war years as Park Avenue transformed into a corporate corridor of skyscraper headquarters. Those aging office towers, however, were losing their competitive edge of prime location to buildings in new districts, such as Battery Park City’s World Financial Center (now renamed Brookfield Place) and, in the early 2000s, a redeveloped Times Square, as well as, recently, the rebuilding of the World Trade Center.

Toward the end of the Bloomberg administration in 2012, the NYC Department of City Planning (DCP) outlined a plan that would create incentives for the private sector to reinvigorate and “green” the Grand Central district with new buildings or by retrofitting older structures. The DCP proposed an increase in the maximum floor area (FAR) allowed for blocks between 39th and 57th streets and Third and Madison avenues, an area they termed East Midtown. Through the purchase and transfer of air rights, in particular the unused air rights of designated landmarks such as Grand Central Terminal and St. Patrick’s Cathedral, developers could assemble up to twice the floor area allowed under the prevailing zoning regulations. In exchange for this up-zoning, the City required improvements – at the developer’s expense – to underground connections to transit and the creation of new public amenities such as pedestrianized streets and new plazas.

A precedent for the East Midtown Rezoning, which was passed by the City Council in 2017, was One Vanderbilt, a new tower designed by Kohn Pedersen Fox Associates (KPF) now under construction that will rise to 1,401 feet to become the tallest office building in Midtown. The rendering at the right shows the shifting status of the signature towers of the 21st century skyline as the Art Deco spires of the Chrysler Building and Empire State will be overtopped almost a century after their heyday. A recently announced project that will make use of the new zoning rules is a new headquarters for JPMorgan Chase at 270 Park Avenue, which will require the demolition of the existing 1961 building to create a taller, 70-story skyscraper.

Another tower which preceded the area rezoning, 425 Park Avenue, designed by Foster + Partners, shown in the rendering on the upper right, is scheduled to open in 2019.

ONE VANDERBILT

One Vanderbilt, 51 East 42nd Street

Owner/Developer: SL Green Realty Corp.

Architect: Kohn Pedersen Fox Associates (KPF)

Structural Engineer: Severud Associates Consulting Engineers

Height: 1,401 ft. | 427 m. | 58 floors

G.F.A.: 1,750,212 ft² / 162,600 m²

This model, designed by the architectural firm KPF, shows the building’s design of four interlocking volumes, revealed at the top of the structure. The massing of the building, which slopes away from Grand Central, has a decidedly more contemporary style than the setbacks of many of the surrounding 70 to 80-year old buildings. The facade of glass and glazed terra-cotta also stands out from the many stone and brick edifices. To maximize height with limited FAR, One Vanderbilt has fewer stories, and higher ceilings, than other skyscrapers of comparable height.

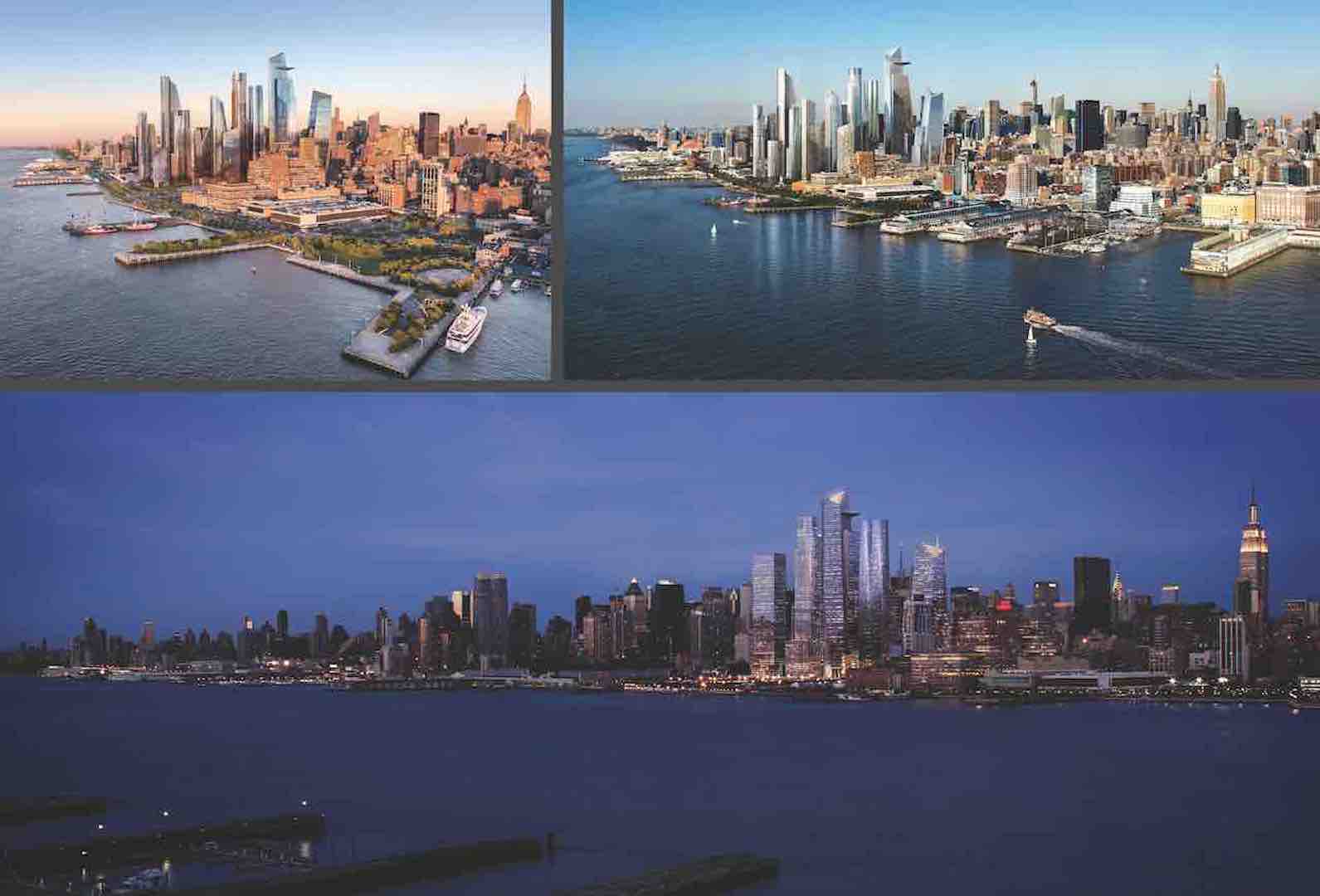

WEST SIDESKYLINE, HUDSON YARDS

An entirely new skyline is taking shape on Manhattan’s west side between the central business district of Midtown South – generally considered to be bounded by Eighth Avenue (which is the border in the wood Chesko model on display) – and extending to West Street and the Hudson River waterfront. The core of this new district is Hudson Yards, 26 acres of mixed-use development that includes 16 skyscrapers, both commercial and residential, as well as retail and cultural spaces, totaling 18 million square feet. They are being built, at immense expense, on a new platform over the West Side Rail Yard, the area of train tracks owned by the Metropolitan Transit Authority (MTA) which uses the ground-level tracks to park Penn Station’s commuter trains between rush hours. Created under a master plan overseen by New York City and the MTA, Hudson Yards is being developed by a partnership of Related Companies and Oxford Properties Group. It constitutes the largest private real estate development in U.S. history. The massive project is being designed and constructed in two phases: the six skyscrapers of the East Yards, which are now all nearly topped out and can be seen from all around the city, have an estimated completion date of 2022. The West Yards are still undergoing design.

Hudson Yards was planned in the Bloomberg Administration and initiated by a competition to develop the site, ultimately won by Related with a master plan by KPF, who are also architects for the two tallest skyscrapers, 30 and 10 Hudson Yards. The government’s goal was to stimulate a westward expansion of the central business district through tax incentives and tax-increment financing (TIF) that was used to fund an extension of the Number 7 line across 42nd Street to a new 34th Street-Hudson Yards subway station. After the financial crisis of 2008-2009 eased, development activity in the entire district began to accelerate. Several simultaneous projects led by different entities, including the new office towers of Manhattan West on Ninth Avenue, and to the north, as well as a concentration of smaller residential buildings, have risen at the edges of the Hudson Yards platform, and especially along the High Line elevated park. Today, the City’s ambitious plan to channel dense new growth into underdeveloped areas of Manhattan seems an “overnight” sensation.

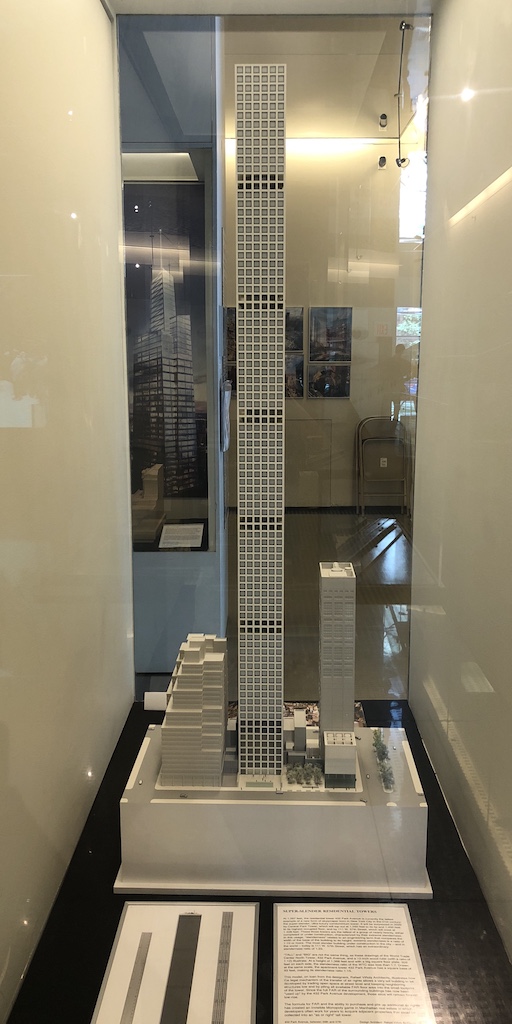

SUPER-SLENDER RESIDENTIAL TOWERS

A new form in skyscraper history has evolved in New York over the past decade: the super-slim, ultra-luxury residential tower. These pencil-thin periscopes — all 50 to 90+ stories — use a development and design strategy of slenderness to pile their city-regulated maximum square feet of floor area (FAR) as high in the sky as possible to create ultra-luxury apartments and spectacular views.

432 Park Avenue, between 56th and 57th Streets

Developer: CIM Group and Macklowe Properties

Design Architect: Rafael Viñoly Architects PC

Architect of Record: SLCE

Height: 1396 ft.| 426.11 m. | 96 floors

G.F.A.: 74,322 m² / 799,995 ft²

At 1,397 feet, the residential tower 432 Park Avenue is currently the tallest example of a new form of skyscraper born in New York City in the 21st century: the super-slender, ultra-luxury condominium tower. It will be surpassed in 2020 by Central Park Tower, which will top out at 1,550 feet to its tip and 1,450 feet to its highest occupied floor, and by 111 W. 57th Street, which will crest at 1.428 feet. These three towers are the tallest of a group of nearly twenty, either completed or under construction, characterized by their extreme slenderness. In this usage, “slenderness” relates to an engineering term that compares the width of the base of the building to its height: extreme slenderness is a ratio of 1:10 or more. The most slender building under construction in the city – and in the world – today is 111 W. 57th Street, which has an extraordinary slenderness ratio of 1:23.

“TALL” and “BIG” are not the same thing, as these drawings of the World Trade Center North Tower, 432 Park Avenue, and a 12-inch wood ruler (with a ratio of 1:12) illustrate. At a height of 1,368 feet and with a big square floor plate, 209 feet on each side, the slenderness ratio of the WTC was less than 1:7. Drawn at the same scale, the apartment tower 432 Park Avenue has a square base of 93 feet, making its slenderness ratio 1:15.

This model, on loan from the designers, Rafael Viñoly Architects, illustrates how the legal mechanism of the transfer of air rights allows a very tall building to be developed by trading open space at street level and keeping neighboring structures low and by piling all available FAR floor area into the small footprint of the tower. Since the full FAR of the surrounding buildings has now been "used up" by the 432 Park Avenue development, those sites will remain forever low-rise.

The formula for FAR and the ability to purchase and pile up additional air rights has created an invisible Monopoly game in Manhattan real estate in which developers often work for years to acquire adjacent properties that could be collected into an "as or right" tall tower.

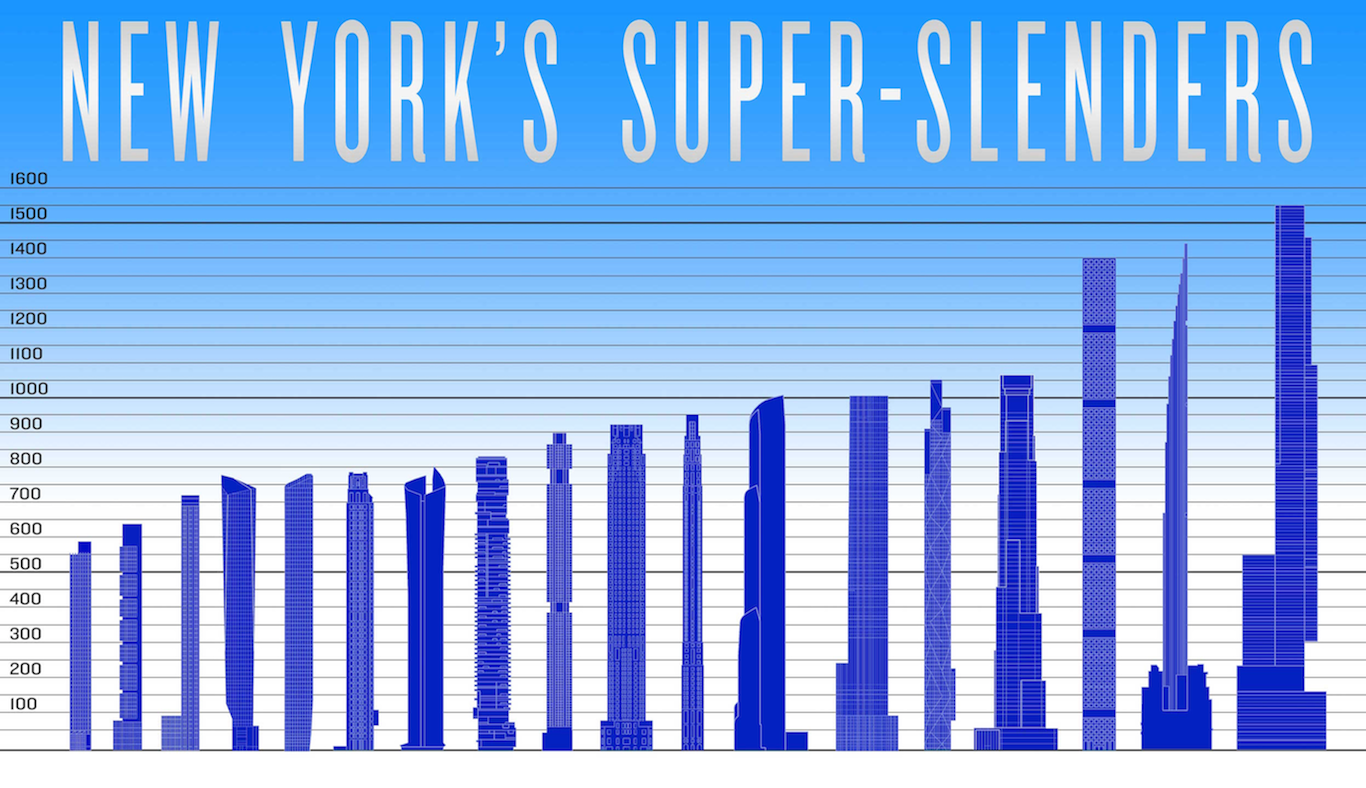

A NEW TYPE: SUPER-SLENDER TOWERS

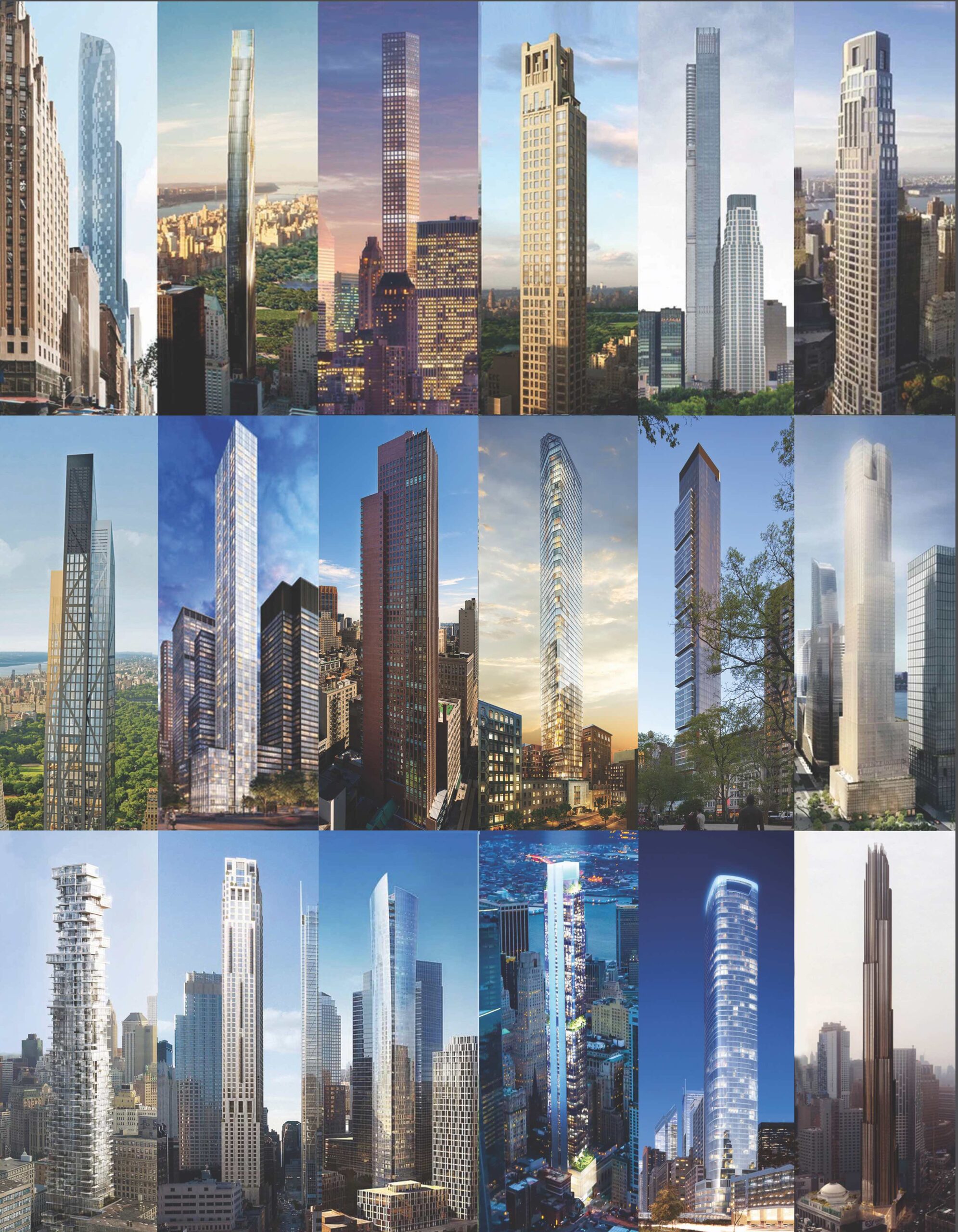

The basic, yet complex, principles of the economics, engineering, and design of this new type were first identified and detailed in The Skyscraper Museum’s 2013/14 exhibition SKY HIGH & the Logic of Luxury: the full text and images of that show are archived on our website skyscraper.org. At that time, there were a dozen super-slenders in development, but only one tower under construction. All of those towers are now completed or under construction, and they have been joined by at least ten more projects. In fall 2016, the Museum created the grid of 18 renderings and the chart of elevation silhouettes, both reproduced here, to update the list. All of these buildings are now either completed or in construction, and few additional projects are in early stages. In lower Manhattan, 45 Broad Street will rise 1,100 feet and have a slenderness ratio of 1:18.

As the Museum’s chart makes clear, the defining characteristic of these new towers is not height, but slenderness. Slenderness is an engineering term that describes the ratio of the width of a building’s base to its height. All of the super-slender towers here have a ratio of at least 1:10, and the thinnest to date, 111 W. 57th Street, is 1:23.

Both prime neighborhoods and great views have added value in New York. Many developers say that apartment buyers shop first for neighborhood, then views, then amenities. In the new crop of super-slender towers, the value of views is clearly the driving force for the tower form. Central Park is the gold standard, but other geographies also have great appeal if they can command climb to 600 to 800 feet or taller and command sweeping panoramas of the city.

The renderings of the 18 slenders above are organized by neighborhood. The top row groups the buildings near the southern end of Central Park and especially on the posh cross-town commercial 57th Street, nicknamed “Billionaires’ Row.” The middle row are located in midtown, near Madison Square, and in Hudson Yards (which has evolved to be only marginally slender). The bottom row are all in lower Manhattan, except the last building, which will become the tallest building in Brooklyn. Designed by 13 different architectural firms in a wide range of styles from historical to avant-garde and clad in materials from limestone to all-glass curtain walls, the renderings underscore that slenderness is the unifying characteristic of the new typology.

Top: One57, 111 West 57th Street, 432 Park Avenue, 520 Park Avenue, Central Park Tower, 220 Central Park South. Middle: 53W53rd, 100 E 53rd Street, Sky House, 45 E 22nd Street, One Madison, 35 Hudson Yards. Bottom: 56 Leonard, 30 Park Place, 111 Murray Street, 125 Greenwich Street, 50 West Street, 9 DeKalb Ave. Images courtesy of the respective architects.

NEW TERRITORIES: EAST RIVER WATERFRONT

Manhattan’s East River waterfront has recently become a new territory for tall towers and innovative development projects. On the Lower East Side – the former area of dense blocks of 19th century tenements that were demolished and replaced in the 1940s through the 1960s with great swaths of “towers in the park” public housing – an 80-story luxury condominium has topped out and will open in 2019. One Manhattan Square, an 800-foot all-glass tower contains 815 apartments and is branded as a “vertical village.” The project offers an impressive list of amenities to attract owners, including supermarket, basketball court, bowling alley, theater, fitness center, pool, pet spa, and outdoor garden, but the main marketing appeal for the $1.2 to $4.5 million apartments is unquestionably the spectacular panoramic views.

Sited just north of the Manhattan Bridge in an area called Two Bridges, One Manhattan Square will be joined by a very nearby neighbor, 247 Cherry Street, which will rise even taller to 1,008 ft. Designed by SHoP Architects and clad in glass and green terra-cotta panels, similar to their ultra-luxury 111 W. 57th Street, this tower will, however, contain 639 units, 25% of which will be permanently designated as affordable and will be distributed throughout the building. Also planned for sites just north are three additional towers that are under Department of City Planning review, but not shown in the renderings here.

Farther north on the East River are a pair of residential towers connected by a sky bridge that includes a pool and a lounge. Called the American Copper Buildings, the north and south elevations are covered in a copper skin, giving a warm tone that captures and reflects sunlight.