The Museum's October 2013 through June 2014 exhibition SKY HIGH & the logic of luxury was documented in an online version that was hard-coded and buggy. All the content of that site is transferred here on a new platform, but without changing tenses from present to past.

SKY HIGH examines the recent proliferation of super-slim, ultra-luxury residential towers on the rise in Manhattan. These pencil-thin buildings—all 50 to 90+ stories—constitute a new type of skyscraper in a city where tall, slender structures have a long history.

Sophisticated engineering and advances in material strengths have made these spindles possible, but it is the excited market for premium Manhattan real estate that is driving both heights and prices skyward. Predicated on Central Park views and other exceptional vistas, these areas appeal to a distinct clientele to whom developers direct their marketing psychology. The reception has been extraordinary: some penthouses are reported in contract for more than $90 million.

Despite what seems like irrational exuberance, these super-slender towers are shaped by a "logic of luxury." Expensive land and air rights, "starchitect" design fees, special engineering and construction, extra-high ceilings, and abundant amenities all factor in a simple math that stratospheric sale prices justify. SKY HIGH explores this new arena of architecture and elevated standard of living.

Image: The Skyscraper Museum

*In 2020, the Museum updated the list and graphic of "New York's Super Slenders" and presented them in a scrolling list with images, IDs, and descriptions. There are 18 buildings included in that survey. Where relevant, the entries point back to their inclusion in SKY HIGH.

A NEW TYPE OF SKYSCRAPER

The super-slim towers featured in this exhibit are a different sort of skyscraper-not unprecedented, but definitely a new formula for development. While they are tall, they are not defined as much by their vertical height as by their slenderness.

There are six projects detailed in the show that fit our criteria of slenderness. There are another six at least that are on the drawing boards or have permits filed, but which we could not include because the developers declined to participate. Many of these projects are working their way through a sensitive public-review process with community boards and City agencies. Others await financing to advance.

The towers, ordered by their geographies include: on the corridor of 57th Street - One57; 432 Park Avenue; and 111 W. 57th, a project recently redesigned by SHoP for a tower of c.1,300 ft. that will have an extraordinary slenderness ratio of 1:23. The MoMA Tower designed by Jean Nouvel that had won City permission for a reduced height of 1,050 ft., would have been an important example on our walls, but the developer declined to participate.

Downtown, 56 Leonard is under construction and the Four Seasons at 30 Park Place is again moving forward after plans were halted by the 2008 banking crisis. In September, another downtown project, 50 West Street, revived from a recession-induced hiatus, became a late addition to our walls.

In Midtown West, Hudson Yards Tower D was another late addition. Although it is a bit zaftig for our slenderness criterion, because it is 70 stories and 870 feet tall, and especially because of its innovative cinched-waist form, we included the all-residential tower in our group.

ZONING & AIR RIGHTS

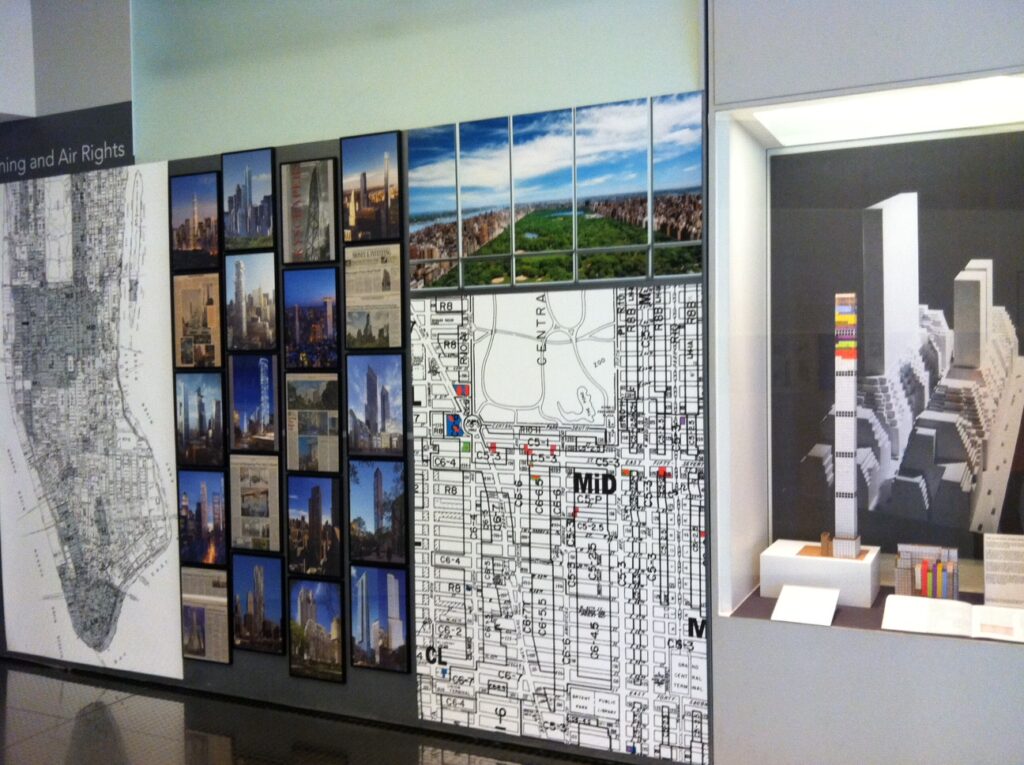

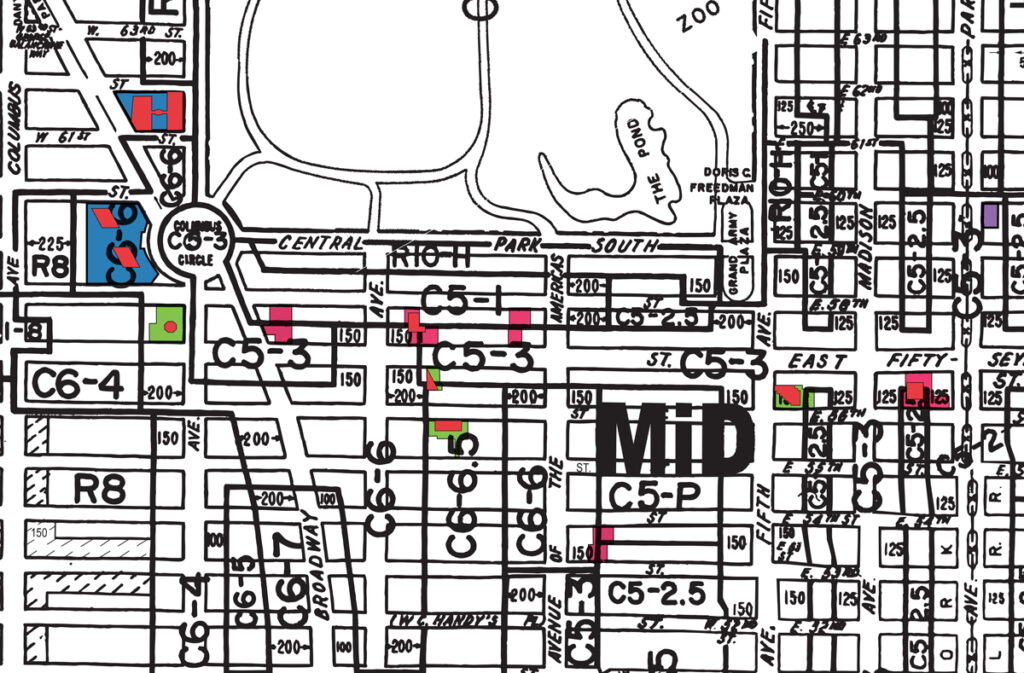

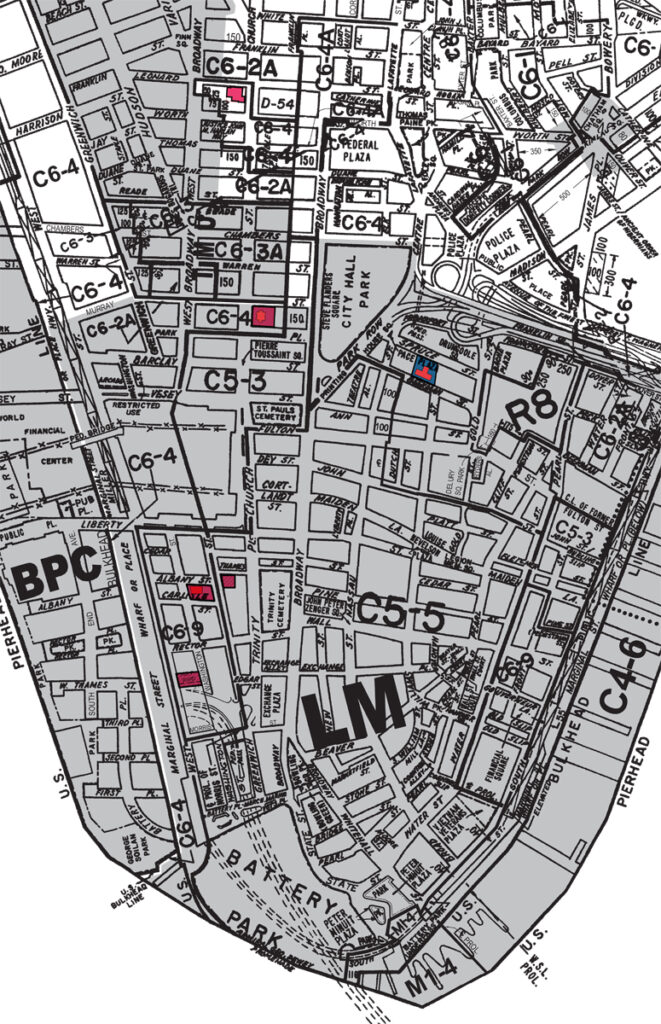

Two maps, enlarged from current Department of City Planning zoning maps of Manhattan carry coding such as C5-3 and C6-4 that refer to the different regulations that govern the delineated area. While the particulars are complicated, the maps make clear that across the city, all development is governed by zoning regulations.

The map is also marked in bright colors that show the footprints of the luxury towers pictured in the adjacent frames. Most of the new buildings cluster along the edge of Central Park, and especially on 57th Street, where they stretch tall to peer at the park over neighboring rooftops.

Other geographies spotted with a few 50-to-70-story slender condos are Midtown South near Madison Square and lower Manhattan.

FAR AND AIR RIGHTS: INVISIBLE MONOPOLY

The first thing one needs to know about development in New York is that every lot in the city is regulated by zoning and has a limit set on its floor area.

In 1961, a new zoning law dramatically reduced the amount of height and bulk that had been allowed by the 1916 zoning law. That hypothetical maximum has been illustrated by reformers who argued that the 1916 bulk was too permissive and dense.

The new law's formula of Floor Area Ratio (FAR) allowed the architect and developer to arrange the permissible FAR in any sort of massing. It also allowed for the purchase and transfer of unused FAR, or "air rights," from adjacent properties.

The formula for FAR and the ability to purchase and pile up additional air rights has created an invisible Monopoly game in Manhattan real estate in which developers often work for years to acquire adjacent properties that could be collected into an "as or right" tall tower.

A model of 432 Park Avenue and the prewar buildings that occupied its site, created by volunteers of The Skyscraper Museum, clearly and colorfully diagrams the transfer of the air rights and the additional FAR of the low-rise buildings on 57th St. that were demolished to make way for the tower. The unused air rights were added to heighten the floor count.

The majority of the FAR assembled in the new tower is reconfigured from the bulk of the former Drake Hotel, represented by the white grid. Since the full FAR of the surrounding buildings has now been "used up" by the 432 Park Avenue tower, those sites will remain forever low-rise.

THE '80S CONDO CRAZE

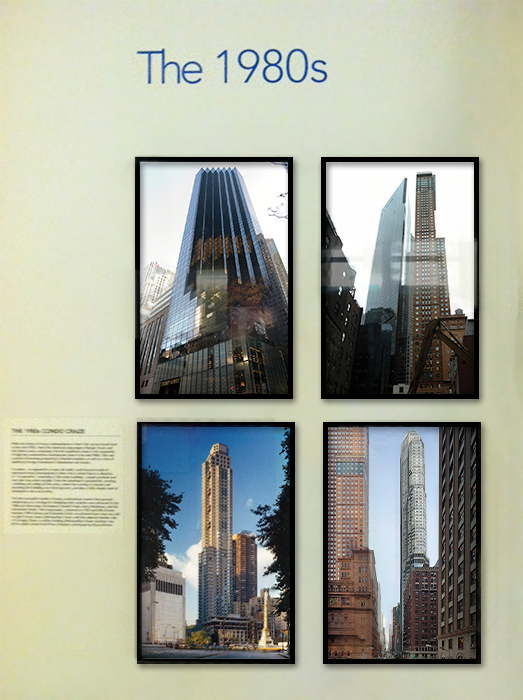

While the history of luxury condominiums in New York can be traced back to the mid-1970s, when the mixed-use skyscrapers Olympic Tower and the Galleria were completed, the first significant phase in the popularity of high-rise condominium development came in the mid-1980s. This was a period of booming prosperity in financial markets, as well as a time of significant foreign investment in Manhattan real estate.

In condos - as opposed to co-ops, the older, much-favored model of apartment-house development in New York in which there is collective, or "co-operative" ownership of the entire building - people purchase and own their own units outright. From the developer's perspective, erecting a building and selling off the units, rather than renting to tenants and operating the building over the long term, provides a fairly simple math of anticipated costs and profits.

The first successful models of luxury condominium towers that pursued slenderness as a strategy for designing their projects were advanced in the 1980s by three major developers: Donald Trump, Harry Macklowe, and the Zeckendorf family. Their skyscrapers, clustered on 57th and 56th Streets between Fifth Avenue and Columbus Circle, are pictured in the image on the left: (top row, left to right) Trump Tower; Metropolitan Tower, with the adjacent slender slab of Carnegie Tower, an office building; Metropolitan Tower; (bottom row, left to right) Central Park Place; CitySpire, developed by Bruce Eichner.

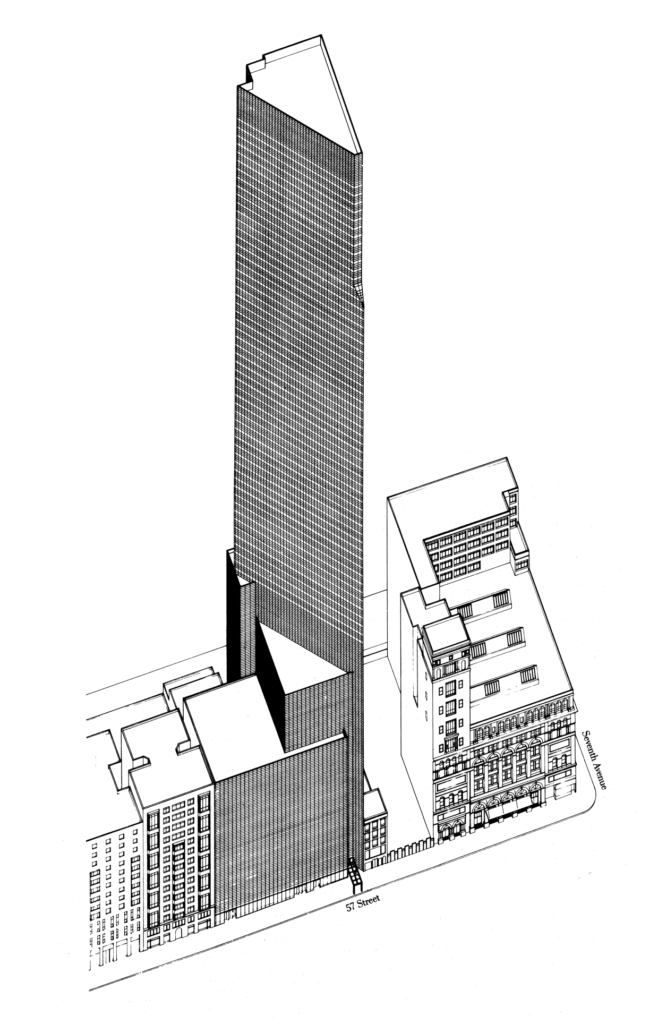

A context model of the full block, from Sixth to Seventh Avenues, encompassing both historic Carnegie Hall and the sites of two slender skyscrapers, was created by the developer Harry Macklowe and was first used for a proposal for one large, mixed-use building that would have occupied the full site of the two lots and used the air-rights of Carnegie Hall.

After the owners of the Russian Tea Room refused to sell their townhouse, thus dividing the two sites, Macklowe went ahead with the slender black glass Metropolitan Tower, marketing it as luxury condominiums with sweeping views of Central Park. Two years later, Carnegie Tower, an unusually slender office building designed by Cesar Pelli, rose only 25 feet from the Metropolitan Tower.

According to Raul de Armas, who was the designer at SOM for the larger Macklowe project, the postmodern skyscraper in the model was merely a "place holder" and not a serious proposal.

*The only building included that is not officially slender in engineering terms is the pair of structures that comprise 15 Central Park West. This building is so key to establishing the high value of apartments in the entire district of the 57th St. and Central Park South corridor that it could not be omitted from this history.

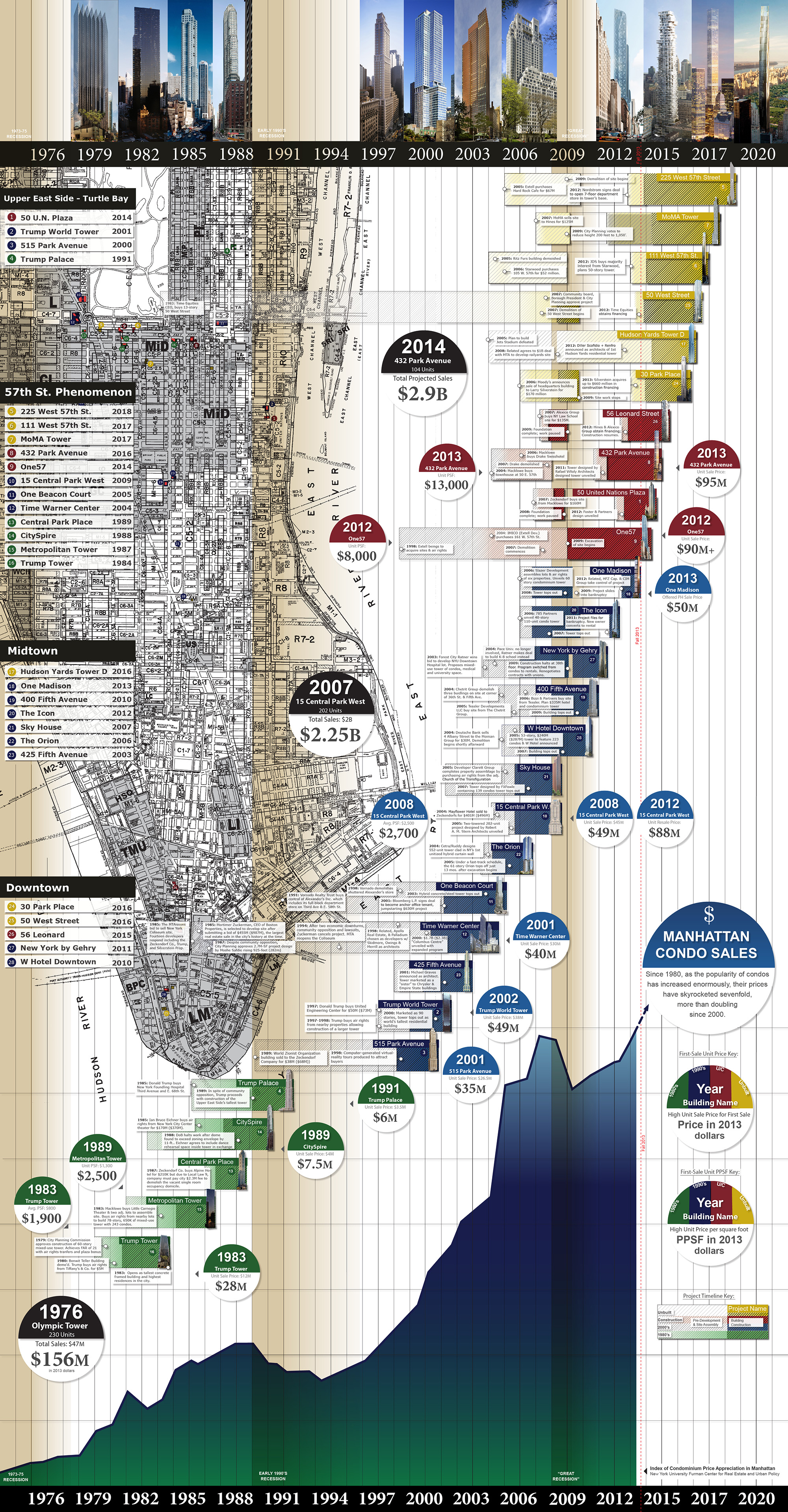

Each of the buildings has its own timeline, separated into two or more sections indicating the land and air acquisition (in white hatching), design, and construction phases. In the balloon circles, the top date refers the year the building was completed; the only exceptions are yellow circles, meaning "under construction." The bottom of the circle shows the price of the highest-priced unit in 2013 currency. Click on the timeline to enlarge it. A detail of the timeline is below.

SKY HIGH PRICES

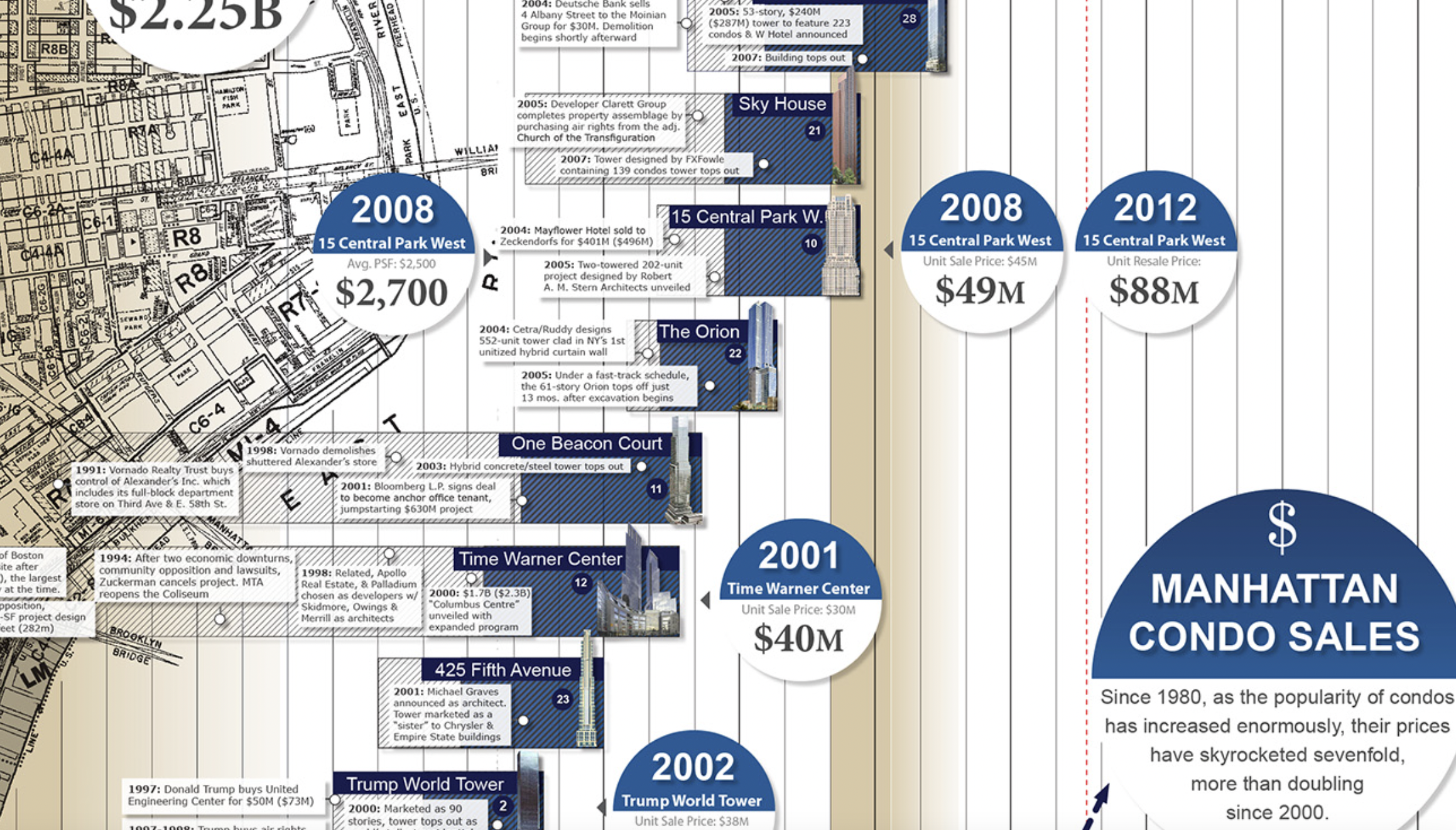

There is a wealth of information on this graphic, which was created by Ondel Hylton for The Skyscraper Museum, in collaboration with Carol Willis.

This chart compiles information on 28 condominium projects constructed from the late 1970s and 1980s–the beginning of the condo era in New York City–through the end of this decade. The buildings included constitute all the projects during this period that share the inseparable characteristics of slenderness and a target luxury market.*

The base map locates all the projects, which are color-coded by construction era and organized by districts. The obvious concentration of recent projects on the 57th St. corridor is thus shown in the context of precedents of the 1980s and 1990s. Each project has an individual timeline that spans phases from site assembly to completion and, where available, a balloon that gives the reported first sale of the highest-priced condo unit. Prices are adjusted to 2013 dollars.

Beginning around 2012, sales of condos in ultra-luxury buildings reached $8,000-$10,000 per sq. ft. and in some cases even higher. These records have set a new standard that developers use to raise the budget for project expenses. The "logic of luxury" is the idea that high development costs for a project are good business strategy if they can produce extraordinary profits.

1. 50 U.N. PLAZA, 2014

2. TRUMP WORLD TOWER, 2001

3. 515 PARK AVENUE, 2000

4. TRUMP PALACE, 1991

5. 225 WEST 57TH STREET, 2018

6. 111 WEST 57TH STREET, 2017

7. MoMA TOWER, 2017

8. 432 PARK AVENUE, 2016

9. ONE57, 2014

10. 15 CENTRAL PARK WEST, 2007

11. ONE BEACON COURT, 2005

12. TIME WARNER CENTER, 2004

13. CENTRAL PARK PLACE, 1989

14. CITYSPIRE, 1988

15. METROPOLITAN, 1987

16. TRUMP TOWER, 1984

17. HUDSON YARDS TOWER D, 2016

18. ONE MADISON, 2013

19. 400 FIFTH AVENUE, 2010

20. THE ICON, 2012

21. SKY HOUSE, 2007

22. THE ORION, 2006

23. 425 5TH AVENUE, 2003

1. 50 U.N. PLAZA, 2014

24. 30 PARK PLACE, 2016

25. 50 WEST STREET, 2016

26. 56 LEONARD, 2015

27. 8 SPRUCE STREET, 2011

28. W HOTEL DOWNTOWN, 2010

TRADITIONAL ARCHITECTURE

This part of the exhibition features buildings from 2000 to the present that exemplify traditional styles and materials of residential architecture, in particular, a treatment of the facade that employs a pattern of masonry walls (stone cladding) and individual, framed windows, as well as decorative ornament such as columns, quoins, and balconies. These wall-and-window alternations also create more traditional interiors than all-glass facades and also hide structural columns within the walls.

Model of 15 Central Park West on loan from Zeckendorf Development.

15 Central Park West

Called a "magnet for billionaires," 15 Central Park West does not belong to the formal type of the super-slender towers, but it does stand as the grand-daddy of sky high prices, establishing the high mark in 2008 of a $45 million first sale, and resale prices in 2012 of $88 million.

Its traditional architectural values of masonry monumentality, along with expansive picture windows with spectacular Central Park views and exceptional amenities throughout the building, made it an immediate success and pumped-up the ambitions of the next wave of development.

15 Central Park West, 2005-2007

Developer: Zeckendorf Development LLC

Design Architect: Robert A.M. Stern Architects

Architect of Record: SLCE Architects

Structural Engineers: WSP Cantor Seinuk

MEP Engineers: Flack + Kurtz

Height: 550 ft | 168 m | 43 floors

G.F.A.: 886,000 Sq. Ft | 82,312 Sq. m.

Units: 231 (202 Condominiums, 29 Staff or Guest Suites)

Model of 515 Park Avenue on loan from Zeckendorf General Partnership.

515 Park Avenue

A model of 515 Park Avenue, another project by the developer of 15 Central Park West, the Zeckendorf family, was designed by the architect Frank Williams, who also favored traditional masonry and punch windows. With its series of setbacks and slender top stories this tower was a real estate success story, garnering $26.5 million for its penthouse in 2001.

515 PARK AVENUE, 2001

Developer: Zeckendorf General Partnership

Whitehall Real Estate Fund

Architect: Frank Williams and Partners

Structural Engineer: WSP Cantor Seinuk

Model on loan from Zeckendorf Development

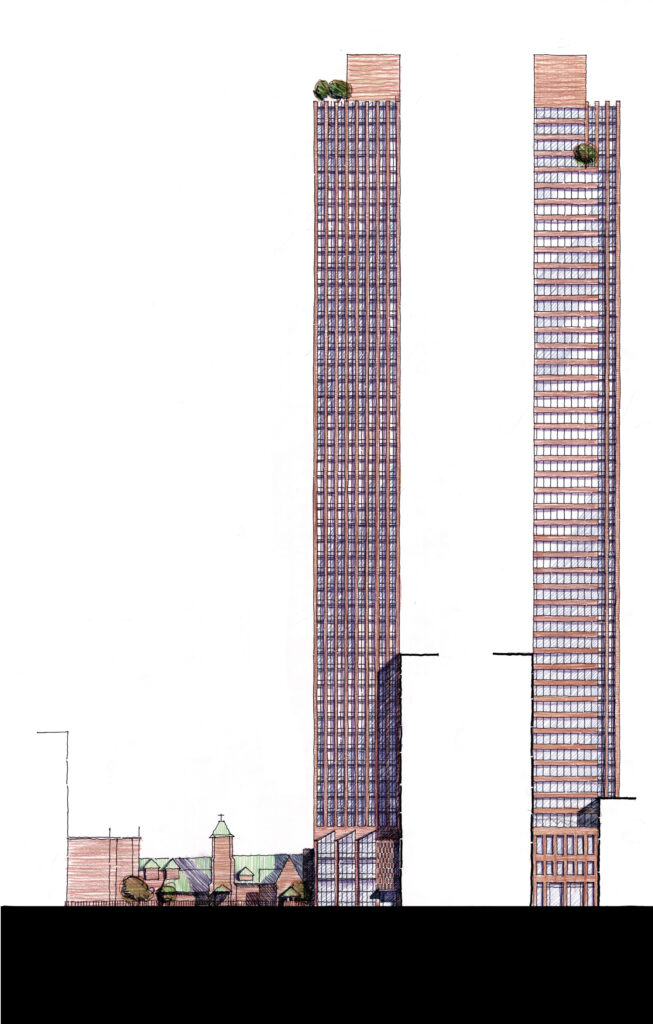

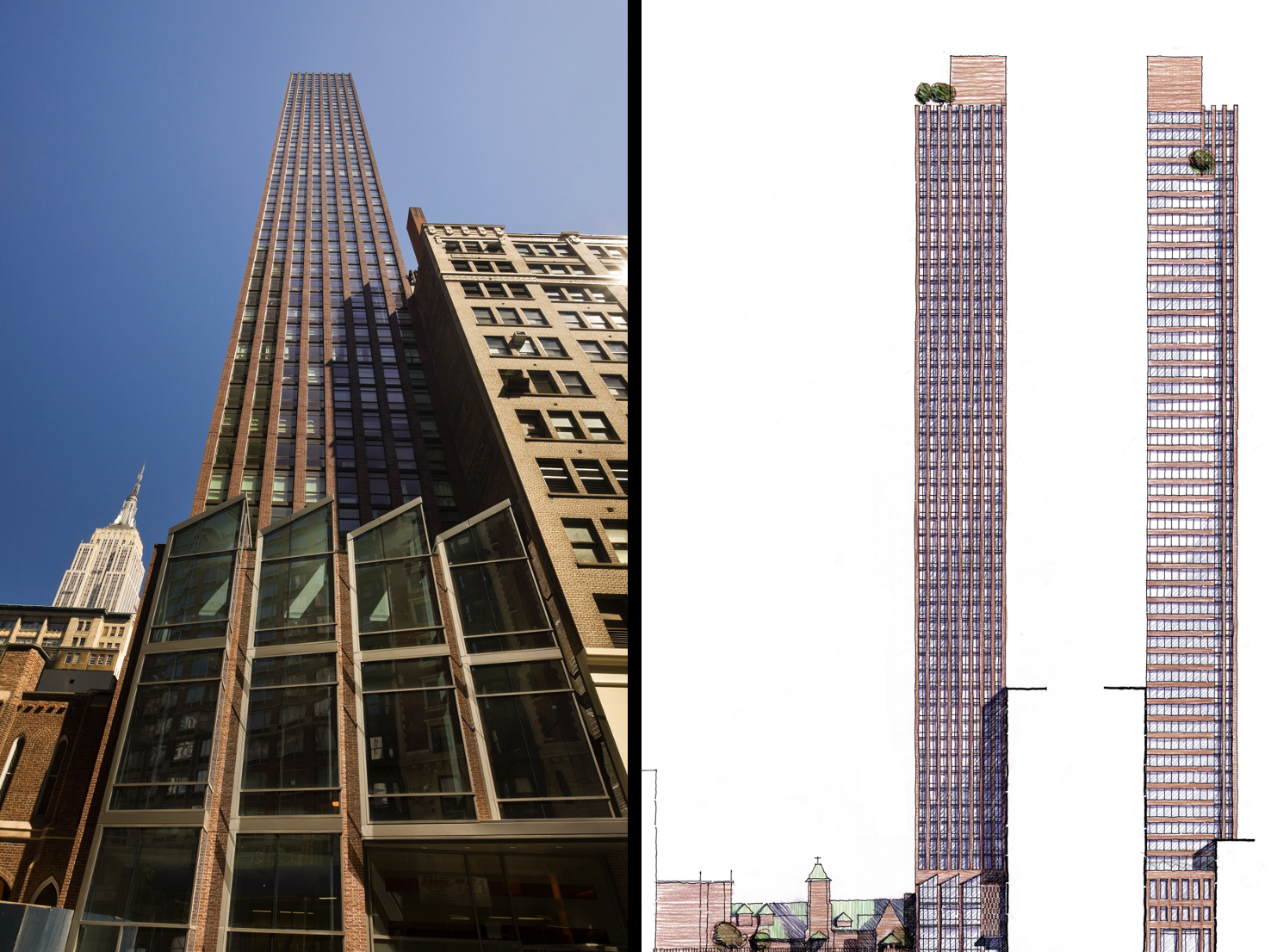

Left: View of Sky House from 29th St. Photograph by David Sundberg/ESTO. Right: Elevation drawing, courtesy of FXFOWLE.

Sky House

One of the loveliest buildings of the post-2001-pre-2008 moment of slenderness is Sky House, a 55-story slab rising on a lot just 45 ft. wide on 29th St. and running through the block to 30th St., midblock between Fifth and Madison Ave. Having purchased air rights from the landmarked red brick "Little Church Around the Corner," the developers, architects FXFOWLE, and engineers WSP Cantor Seinuk created a contextual design that emphasized verticality in the close set, brick-faced structural columns. Their exploration of the design process is described in a series of lectures for the Museum in conjunction with the exhibition VERTICAL CITIES: HONG KONG | New York.

Sky House, 2008

11 East 29th Street

Developer: The Clarett Group

Architect: FXFOWLE Architects

Structural Engineer: WSP Cantor Seinuk

Height: 588 ft | 139 units

A rendering 30 Park Place with the Woolworth Building to its left and towers of the World Trade Center to its right. Image credit: dBox. Courtesy of SPI.

30 Park Place

As with the earlier design for 15 Central Park West, Robert A. M. Stern Associates employs a classical vocabulary of masonry walls and picture windows to refer to the traditions of historic architecture, in counterpoint to both the all-glass office towers of the World Trade Center—both planned and currently under construction—and to the Gothic spire of the Woolworth Building which occupies the same block, just east of 30 Park Place. In its height and slenderness, 30 Park Place relates to the office-building ensemble at Ground Zero also being developed by Silverstein Properties.

The 82-story limestone-clad structure is a mixed-use project, with a 185-room hotel, The Four Seasons Hotel New York, Downtown, on the lower 21 floors. The remainder of the tower, known as the Four Seasons Private Residences New York at 30 Park Place, will comprise 157 luxury condominiums, including full-floor penthouses and setback terraces, with some private residences as large as 6,000 square feet.

Using slenderness as a strategy to lift its residences high in the sky, the tower also pulls as far away as possible from the Woolworth Building—once the world's tallest building—which it now overtops. A courtyard separates the two, allowing 30 Park Place to rise, as does Woolworth, as a free-standing structure.

Four Seasons Downtown Hotel and Residences at 30 Park Place

Expected Completion Date: 2016 (actual completion: 2016)

Developer: Silverstein Properties

Design Architect: Robert A.M. Stern Architects

Architect of Record: SLCE Architects

Structural Engineers: WSP Cantor Seinuk

MEP Engineers: Flack + Kurtz

Height: 926 ft. | 282 m. | 82 floors

WINDOW WALLS

The all-glass wall, a facade treatment generally associated with office buildings, has been adopted in many of the new super-slender towers as much for its thrilling effects and "look of luxury" as for its relative economy due to the relative ease of construction of IGUs (integrated glass units).

The appearance of a uniform glass "skin" became popular in the 1950s and 60s with corporate towers such as Lever House (even though spandrel glass was not transparent from the interior). The first skyscraper to use full floor-to-ceiling glass was the Seagram Building, according to Phyllis Lambert, who selected the architect Mies van der Rohe and worked with him as a client on the commission. The all-glass curtain wall became an expression of modernity and of quality (although it also became nearly ubiquitous and debased) and it entered the vocabulary of residential architecture in New York in the 1970s and 1980s in projects such as Olympic Tower, Trump Tower, and the Metropolitan Tower.

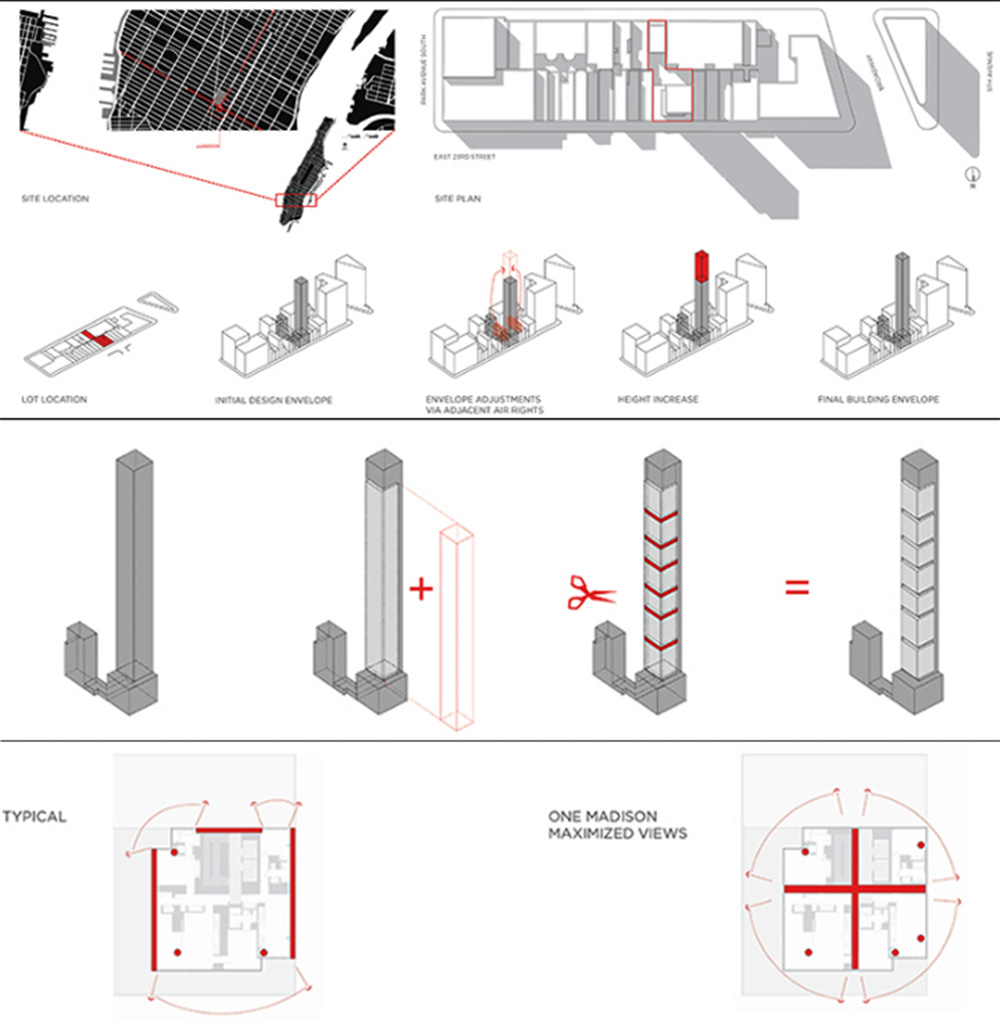

One Madison. Image: David Sundberg, ESTO.

From top to bottom: Diagrams showing site location and transfer of air rights, Massing Design diagrams, Comparison of structure and views.

Expected Completion Date: 2010 (actual completion: 2010)

Developer: Related Companies, CIM Group, and HFZ Capital Group

(first developed by Slazer Enterprises)

Architect: Cetra/Ruddy Architecture, PLLC

Structural Engineers: WSP Cantor Seinuk

MEP Engineers: MGJ Engineering, P.C.

Height: 617 ft | 188 m | 47 floors

G.F.A.: 163,500 sq. f.t | 49,834 sq. m.

Units: 97

ONE MADISON

One Madison Park, which has been recently renamed One Madison by its new owner/ developer, was largely completed in 2009, but the project hit the market at the beginning of the recession, and the first developers had to declare bankruptcy and sell the building.

Text and images for One Madison were provided by Cetra Ruddy.

Facing Madison Square Park, at the intersection of two major thoroughfares, 23rd Street and Madison Avenue, One Madison is uniquely situated on the Manhattan grid with a prominent axial position. At 620 feet high with a 5,175 square-foot footprint and 50-foot wide base, One Madison is extremely slender, with a ratio of 12:1. The constrained site limited the building's floor plate, necessitating a clever design that would maximize space and views.

Part of the challenge in developing the design, materials, and aspects of the structure, was to create a modern building that was in concert with the fabric of Madison Square Park and the classic architecture of the neighborhood. The main tower shaft is composed of earth-toned bronze glass, enabling the tower to blend with the older surrounding limestone and masonry buildings. Similar in proportion, One Madison and the MetLife tower rise above the neighborhood, creating a dialogue between traditional classism and contemporary architecture.

The tower's modular form is delineated by seven volumetric pods, constructed from clear white and green glass. These cube-like forms deconstruct the building's mass and give it a sense of lightness. Unlike typical residential and commercial buildings, this modular concept creates varied units and a combination of effects allowing for a unique and expressive building form. Floor-to-ceiling glass walls draw the eye outwards to the city, creating a dramatic and picturesque backdrop that changes with the seasons. Cantilevered from the main shaft, the pods lend functionality beyond their aesthetic appeal, extending the tower's 2,700 square-foot floor plate to 3,300 square-feet and modulating the building form. This unique feature grew out of the need to expedite construction on the main tower and from the desire to offer a mix of apartment types, some with terraces.

Residences range from 805 square-foot studios to a 7,143 square-foot triplex penthouse, and the property features luxurious amenities, including a spa, swimming pool, fitness center, media/screening room, children's room, and outdoor terrace park. To create a serene and intimate entry, residents enter the building on 22nd Street, a configuration that also allows for a ground floor commercial space to complement the existing retail activity of 23rd Street.

A promotional video for One57 visualizes architect Christian de Portzamparc's trope as a fountain of rising and cascading water and scintillating surfaces. The camera swivels around the building to show One57 dominating the Midtown skyline.

Courtesy of Extell Development.

One57, 2014

157 West 57th Street

Developer: Extell Development Company

Design Architect: Atelier Christian de Portzamparc

Architect of Record: SLCE

Structural Engineers: WSP Cantor Seinuk

MEP Engineers: AKF Engineers

1004 ft | 306 m | 75 floors

G.F.A: 853,567 sq. ft. | 79,299 sq. m.

Units: 94 Condominiums

ONE 57

The most important building for the evolution of our slender SKY HIGH towers -- following the path-breaking Time Warner Center and 15 Central Park West, which solidified the desirability of the southwest edge of Central Park for luxury addresses and established new records for unit sales -- is One57, which is located mid-block between Sixth and Seventh Avenues, on the north side of W. 57 St., where it enjoys both the glitter of that major commercial cross street and dead-center views of Central Park.

One57 is the breakthrough luxury project of the developer Gary Barnett, whose first real estate venture in New York dates back only to 1994. After erecting the Times Square W Hotel, a 53-story very slender tower completed in 2001, he developed the Orion, a 550-unit tall, slim apartment building on W. 42 St., completed in 2006. Targeted at an ultra-luxury market, One57 combined the program of a hotel and its services and amenities in the lower section and 94 condominium units in the tower.

One57 at once harkened back to the late 1980s and the skinny, straight-up shafts of the Metropolitan Tower, Carnegie Hall Tower, and CitySpire (whose views of the park it now blocks) and pointed forward to the strategy of slenderness used to lift the tower extra high and to use small floor plates to emphasize exclusivity and ultra-luxury. At 1,004 feet tall (306m) and topped out and enclosed in its colorful curtain wall in November 2013, One57 was reported to have more than 70 percent of its apartments in contract, including a penthouse for $90 million.

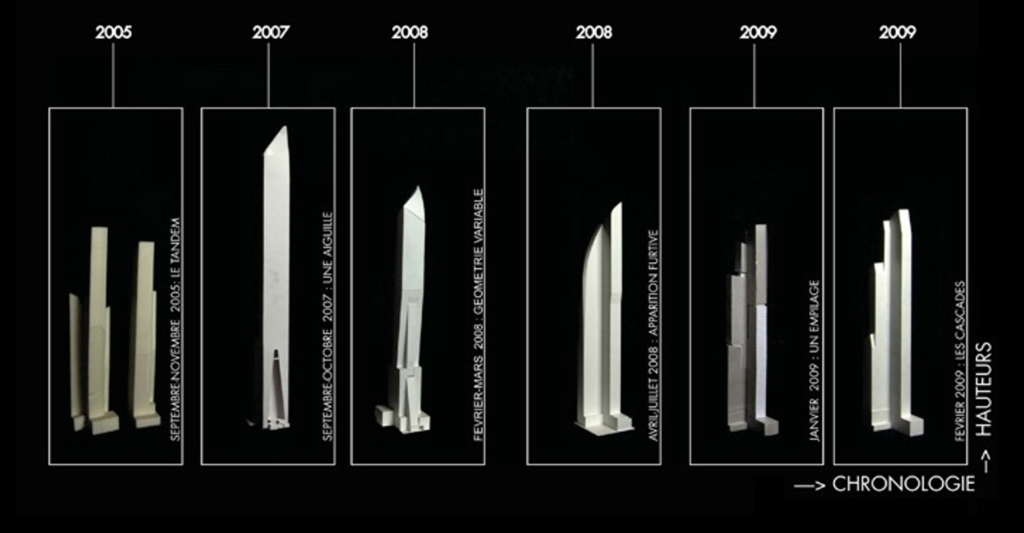

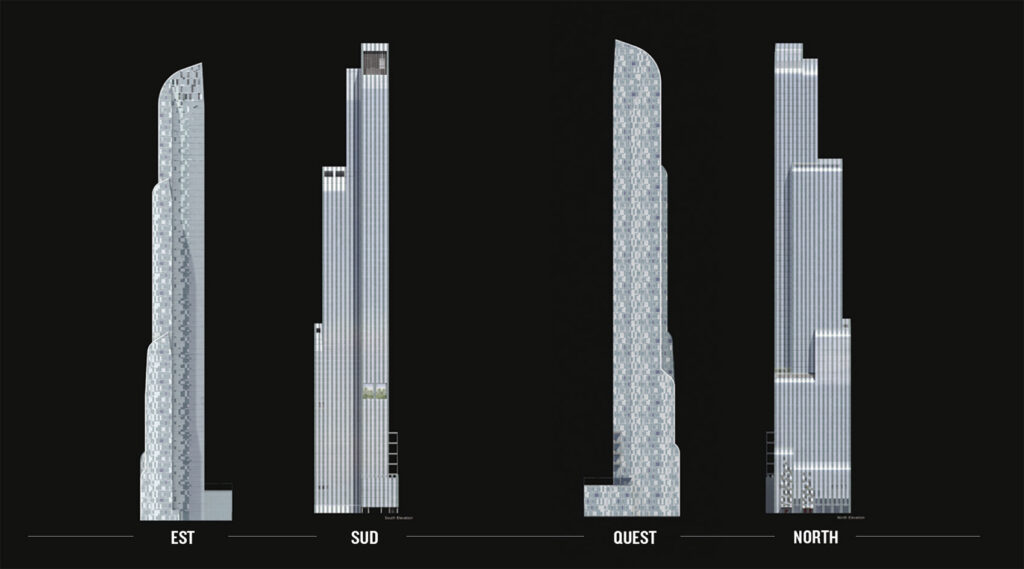

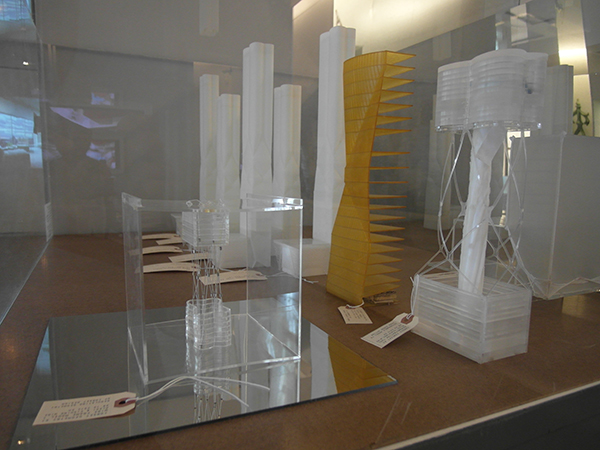

Although Barnett had begun to acquire buildings and air rights as early as 1998, the first design for One57 began in 2005 when the developer commissioned the Pritzker Prize-winning French architect Christian de Portzamparc to prepare design studies for a pair of towers for the two sites one block apart that he owned on W. 57th Street. (The second site is the group of lots that in fall 2013 were in design development by Smith + Gill.) In July 2007, Portzamparc was commissioned to develop the design for the mixed-use, hotel and condominium tower at 157 W. 57 that would rise to 300 meters (c. 1,000 ft.) and thus become the tallest residential building in the city.

The slenderness and massing strategies evolved in dozens of study models in 2008, and the tower reached its definitive form in 2009 in a project the Portzamparc Atelier called "les cascades," referring to the imagery of flowing waterfalls. The curtain wall treatment of varicolored glass panels of blue, gray, and silver reinforced the trope of reflections on water, but Portzamparc also used the term "Klimt effect" to describe the fa�ade, suggesting the mosaic-like decorations of the Viennese modernist painter.

Hudson Yards Tower D

Northeast corner 11th Avenue and West 30th Street

Expected completion: 2019 (actual completion: 2019)

Developer: Related Companies, Oxford Properties Group

Design Architect: Diller Scofidio + Renfro / Rockwell Group

Architect of Record: Ismael Leyva Architects

Structural Engineers: WSP Cantor Seinuk

MEP Engineers: Jaros Baum & Bolles

Height: 870 ft. | 70 floors

G.F.A.: 855,000 sq. ft

Units - 364

HUDSON YARDS TOWER D

The rendering on the left visualizes the eastern section, looking north, of the future West Side extension of Midtown's business district, Hudson Yards. Since 2001, the City of New York, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, and the State of New York have collaborated on a master plan for a 26-acre development site to be built on a platform above the commuter train storage and maintenance yards owned by the MTA-Long Island Rail Road (LIRR). The rail yard is located between West 30th and West 33rd Streets from 10th to 12th Avenues and consists of an eastern portion (Eastern Rail Yard) and western portion (Western Rail Yard), divided by 11th Avenue.

In May 2008, the MTA selected the Related Companies to develop the entire site. Working with a financial partner, Oxford Properties Group, Related has undertaken as its first phase the Eastern Rail Yard - approximately 13-acres that will accommodate approximately 6.6 million gross square feet of mixed-use development, including office, residential, hotel, retail, cultural and parking facilities, and public open space.

The first group of buildings being developed are a pair of skyscrapers of 52 and 80 stories designed by KPF, both principally office buildings, and the 70-story residential Tower D, designed by Diller, Scofidio + Renfro, in collaboration with the Rockwell Group, which anchors the southwest corner of the Eastern Rail Yard at 30th Street and 11th Avenue.

The first commercial high-rise by architects renowned for cerebral and often ironic gestures, Tower D has been nicknamed "the Corset" by the firm, which uses an image of a Victorian undergarment to convey their form-making moves. Below they describe the program of combining rental units in the lower section and condos above through the expression of the distinctive middle section:

A network of crisscrossing straps cinches the tower at its mid-section, squeezing the rectilinear lower half of the building into a curvaceous upper half. The tower emerges from the city block and deviates into fluid contours as it rises to the sky, taking advantage of 360-degree views that open up around the periphery. Normally thought of as brittle and rigid material, glass here is expressed as organic and supple.

The base of Tower D will be conjoined with Culture Shed, a new cultural facility currently in development. The Culture Shed will combine visual arts, performing arts and creative industry.

ENGINEERING SLENDERNESS and WIND-TUNNEL TESTING

Tall buildings must resist overturning due to lateral forces from wind, earthquakes, or even their own weight. Beyond insuring against catastrophic failure, engineers and architects must design structures that do not flex too much, since movement can damage joints, cause leaks, and even break windows and façade panels. Inside, excessive movement can also jostle or jam elevators, crack walls, and cause unnerving creaks and groans. Many people are sensitive to even slight motion in buildings.

Structural engineers use wind-tunnel laboratories to test their designs. Models of 432 Park Avenue were developed for the engineers WSP Cantor Seinuk (now known as WSP Group) by the consulting company RWDI, a testing lab in Guelph, Ontario.

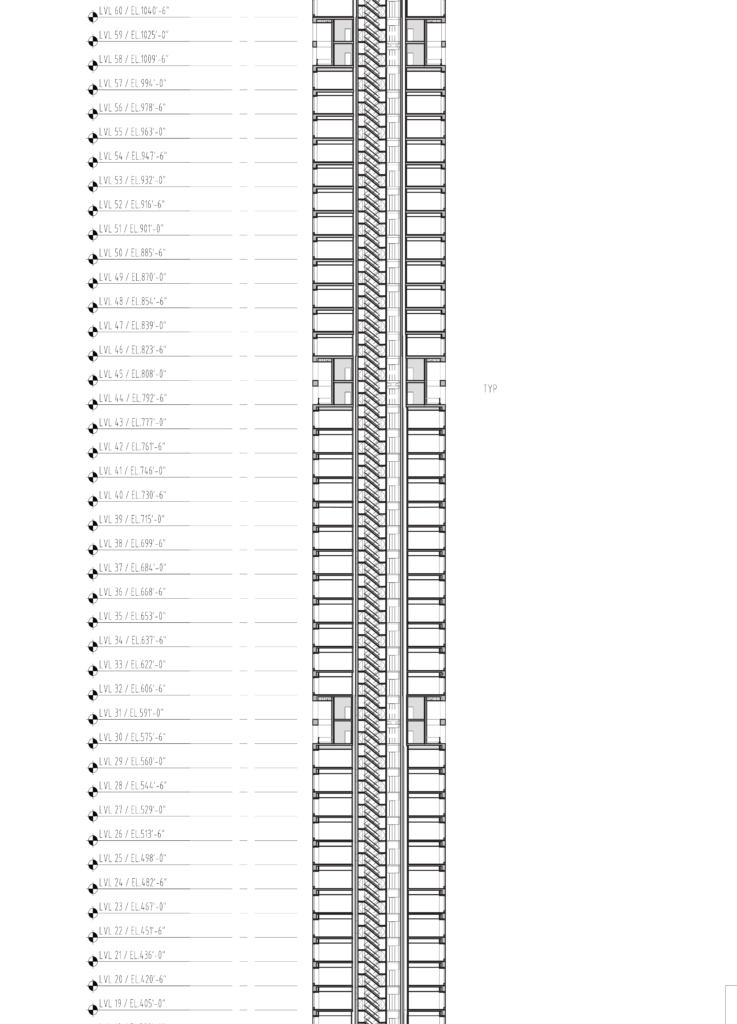

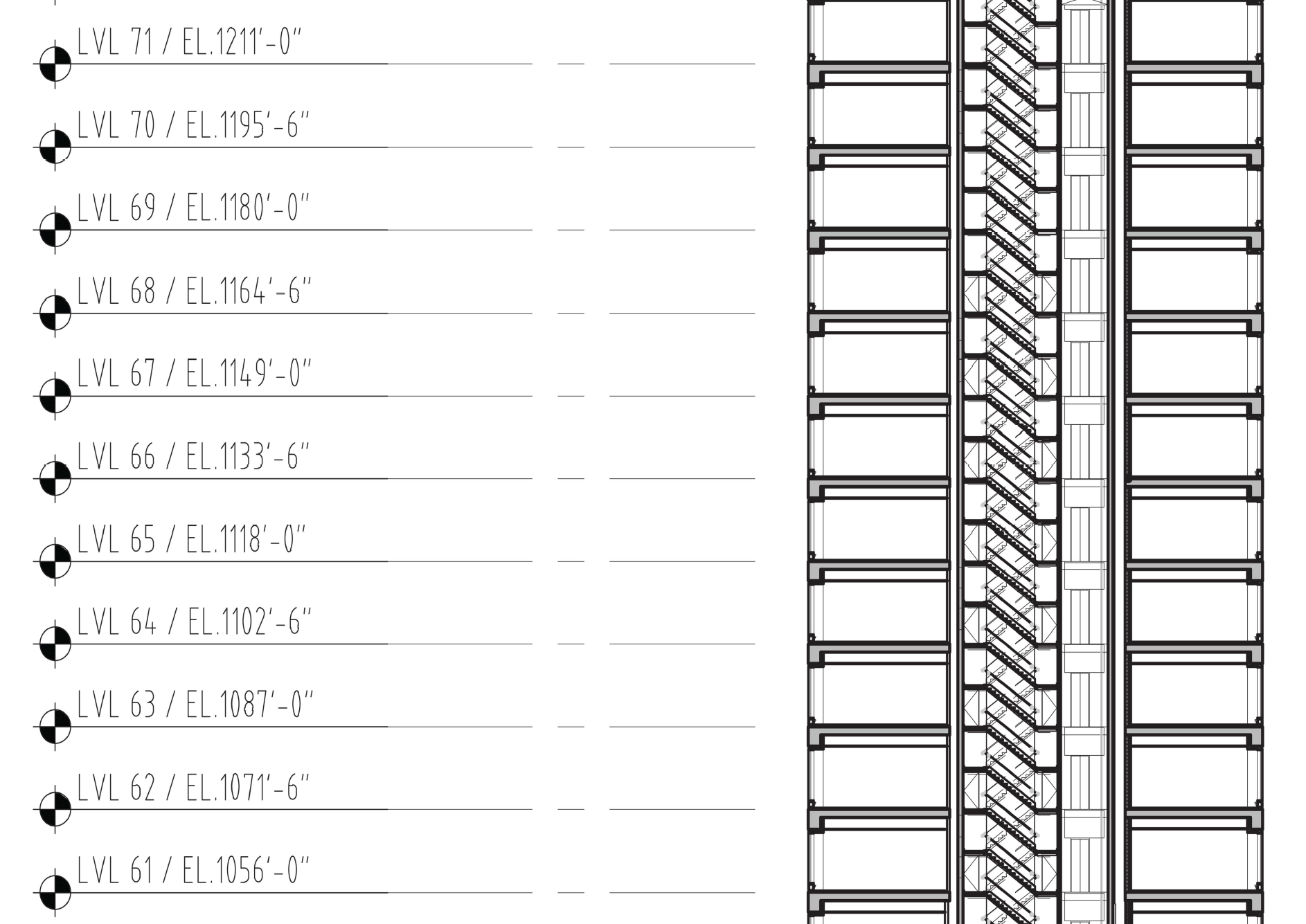

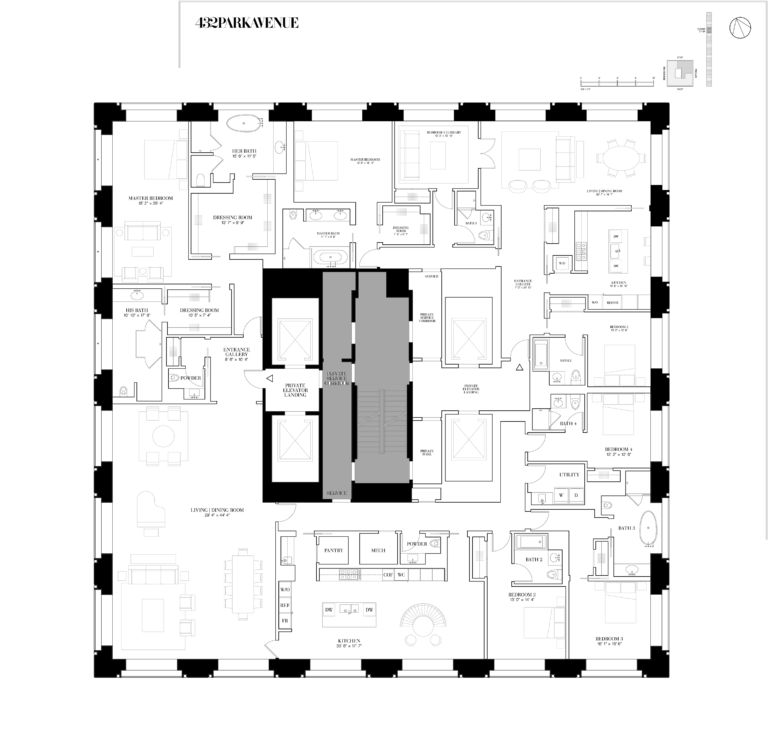

The tower's structural concept is seen clearly in a tall section elevation. As described by the engineers, WSP Cantor Seinuk:

The structure consists of an architecturally-exposed concrete tube system, coupled to a central core with concrete strengths of more than 14,000 psi. A flat slab spans from core to perimeter with no interior columns, giving the interior space planning the maximum flexibility possible. Given the tower's height and aspect ratio of more than 15:1, the efficiency of the structure is of the utmost importance in order to create structure that works harmoniously with the architecture. To that end, every inch of concrete is utilized to provide lateral stability and maximize efficiency.

As with most high-rise buildings, controlling the perceptibility of lateral motion building in high wind conditions is a key design focus. To that end, a series of openings through the structure were developed through wind-tunnel testing that improve the aerodynamics of the building. In addition, two tuned-mass dampers were designed to further reduce lateral accelerations to acceptable levels for the occupant's comfort.

432 Park Avenue, 2015

Between 56th and 57th Streets

Developer: CIM Group and Macklowe Properties

Design Architect: Rafael Vinoly Architects PC

Architect of Record: SLCE

Structural Engineers: WSP Cantor Seinuk, Israel Berger and Associates --curtain wall consultant

MEP Engineers: WSP Flack + Kurtz

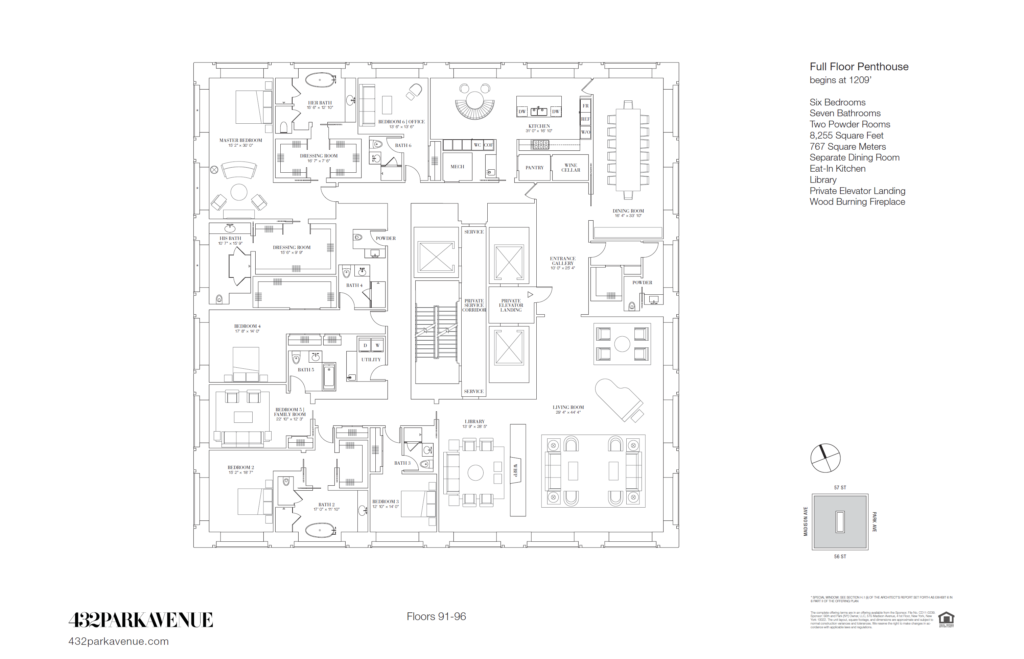

Height: 1396 ft.| 426.11 m. | 96 floors

G.F.A.: 74,322 m / 799,995 ft

Units: 104

432 PARK

With a flat rooftop that squares off at 1,396 feet, 432 Park Avenue, upon its completion in 2015, will become the tallest residential building in New York City and in the western hemisphere. At that height, it will be taller than the 1,368-foot roof of One World Trade Center, as well as of the original WTC Tower 1, which at that height was, from 1971-1973, the world's tallest building.

On February 24th, 2014, architect Rafel Viñoly discussed the design of 432 Park Avenue in the context of his high-rise work and design philosophy at a lecture presented by The Skyscraper Museum. Click here to watch the lecture.

Courtesy of Alexico Group.

Courtesy of Alexico Group.

Video: Tronic Studio. Courtesy of Alexico Group

Expected completion: 2016 (actual completion: 2016)

Developer: Alexico Group/Gerald D Hines Interests

Design Architect: Herzog & de Meuron Architekten

Architect of Record: Goldstein Hill & West Architects

Structural Engineers: WSP Cantor Seinuk

Height: 796 ft | 243 m | 60 floors

G.F.A.: 480,364 sq. ft. | 146,414 sq. m.

Units: 145

56 LEONARD

Designed by the Pritzker Prize-winning Swiss firm Herzog & de Meuron, the tower at 56 Leonard stands apart in several ways from the other projects in the exhibition. Its downtown location at the edge of chic Tribeca, a largely residential neighborhood in an area of converted late-19th century commercial structures, allows it to rise high above surrounding rooftops. Sited just outside the landmark district, and using air rights purchased from the adjacent New York Law School, when topped out in 2014, the tower will stretch to nearly 800 feet and 60 stories.

The unusual staggered silhouette, especially of the upper floors, that earned the nickname "the jenga building" after the game of stacking and balancing wood blocks, also sets the form apart from the towers of the two other Pritzker laureates, Portzamparc, with the the patterned window walls of One57, or the structural expression of the steel frame in Jean Nouvel's MoMA Tower. Herzog & de Meuron evoke a Modernist metaphor of "villas in the sky" by vertically stacking glass-house unit upon unit. The effect is most dramatic on the top eleven stories where the floor slabs cantilever as much as 25 feet and floor-to-ceiling glass and outdoor balconies create a sense of endless space. Below these penthouses, though, there is still insistent variety: the developer claims that each of the 145 units has a unique floor plan.

Since skyscrapers are normally repetitive structures in the vertical dimension, the desire to create all unique units required innovative structural engineering approaches. According to the building's engineers WSP Cantor Seinuk, the structure of stacked, cast-in-place concrete flat plate floors is supported by reinforced concrete columns and shear walls. The central concrete core is supplemented by two sets of outrigger walls and a belt wall connecting the exterior columns to the building's core. The shear walls and columns employ high strength concrete of 12,000 psi at lower levels, reduced to 7,000 psi at higher levels.

In addition they note: "In order to accommodate varying apartment layouts, virtually all the columns had to be relocated at various points using a "walking columns" system-a solution created by introducing one to three-story walls that transfer the load from one column location above to a different column location below. The eccentricity of the transferred load causes an additional lateral force, which is applied to the structure at the top and bottom of the transfer wall. These additional lateral forces are then transferred to the shear wall core through the floor slabs."

Conceived and marketed by the developers as individual artworks, rather than as regular apartments, the condos of 56 Leonard have enjoyed successful sales ever since the project, first designed before the recession of 2008, began construction in 2012. The cache and high value of the Tribeca neighborhood and the developer's commitment to high-profile designers, including a commissioned sidewalk piece by the artist Anish Kapoor, has produced unusually high prices for downtown real estate, including a penthouse in contract for a reported $47 million.

Massing Study. Courtesy of SHoP Architects.

Tower Facade Materiality. Courtesy of SHoP Architects.

Expected completion: 2018 (actual completion: 2021)

Developer: JDS Development/

Property Markets Group

Architect: SHoP Architects, PC

Structural Engineers: WSP Group

MEP Engineers: JB&B

Facade Engineers: Buro Happold

Height: 1300 ft | 396 m | 76 floors

111 WEST 57TH STREET

The feather-thin tower proposed for 111 W 57th St. is the most extreme example in New York to date of a design that uses a development strategy of slenderness. With a ratio of the width of the base to height of 1:23, it will be by far the most slender building in the world.

The stepped-back silhouette of the tower, which uses textured terra-cotta ornament to disguise the concrete shear wall structure, shows the inventiveness of both the architect SHoP and the engineer, the WSP Group. As described by the architects:

Located in the heart of midtown along 57th street, SHoP's design for this approximately 1300 foot tall luxury residential tower is quintessentially New York. The design aims to bring back the quality, materiality, and verticality of historic NYC towers, while taking advantage of the latest technology to push the limits of engineering and fabrication.

The tower massing accentuates its required setbacks along 57th street with a feathering of multiple, thin steps along the south side facade. Each step corresponds with a layer of intricate terra cotta pilasters cladding the east and west facades. The facade is designed to read at multiple scales and vantage points; the shaping of the terracotta creates a sweeping play of shadow and light from the city scale, as the texture of the terracotta panels and inlaid bronze filigree provides richness up close. A minimalist, glass curtain wall along the North facade will take full advantage of the tower's sweeping views of Central Park.

At its base the tower fits with a courtyard wrapped by the existing landmarked Steinway Building designed by Warren and Westmore and completed in 1925. The bulk of the new tower massing is set back from the street to maintain visibility to the three primary sides of the Steinway Building's front tower. The new design will strategically intersect with the historic building to maintain the character and independence of the landmark. This includes preserving the ornate interior Rotunda space, Steinway's main showroom, while providing a new opening along the eastern facade for increasing accessibility and visibility into the space. A dedicated Steinway recital hall will also be included in the historic building to maintain Steinway's presence both in the building and neighborhood.

On March 11, 2014, The Skyscraper Museum presented a lecture and panel discussion on the topic of 111 W. 57th St.. The event featured architects Vishaan Chakrabarti and Gregg Pasquarelli, Partners, SHoP Architects, structural engineer Silvian Marcus, Principal in Charge, WSP Group, and developer Michael Stern, Managing Partner, JDS Development Group. Click here to watch the lecture.

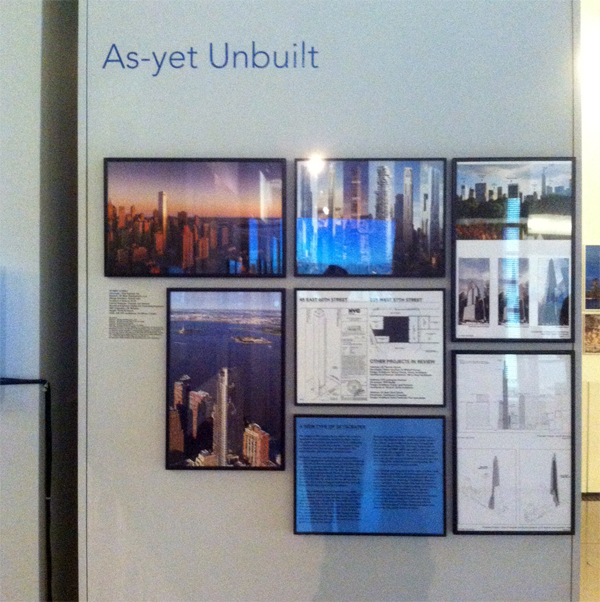

AS-YET UNBUILT (as of 2014)

Several images depict the projects featured in the exhibition, as well as others that at this point can only be mentioned by their addresses or illustrated by public documents. Together they represent a new formal type of skyscraper: the super-slender, ultra-luxury, residential tower.

Of these, three are currently under construction: One57 is topped out and enclosed, but is undergoing interior work; the concrete frame of 432 Park Avenue is rising, as are the concrete slabs 56 Leonard. The others - the feather-thin 111 W. 57th, the shapely, cinched-waist Hudson Yards Tower D, the slim stone-faced shaft of 30 Park Place, and the sleek glass tower of 50 West St. - have not yet begun construction and will take at least two years to be completed.

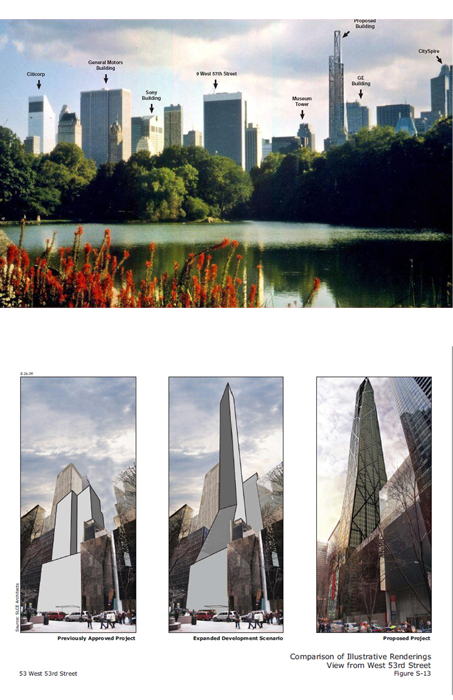

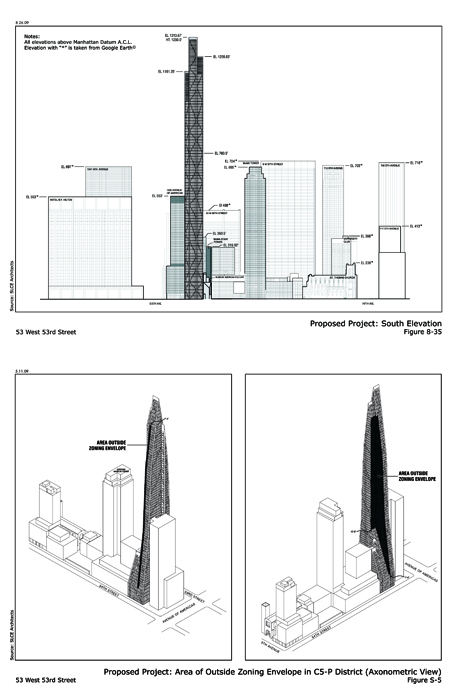

The other buildings that we represent by public documents or just by address have all been discussed in newspapers and on-line articles, blogs, and chat rooms; some have documents filed with the City that are available on line. For various reasons, their developers declined to participate in the exhibition. Best known of these is the project at 53 W 53rd St., generally known as the MoMA Tower, because it is located on a lot that was purchased from the Museum of Modern Art and which will include some gallery space on the lower floors.

"53 West 53rd Street." https://www.nyc.gov/html/dcp/html/env_review/53_west_53.shtml. New York City Department of City Planning.

Designed: 2007, project halted till 2014

Expected completion: 2017 (actual completion: 2019)

Developer: Hines Development

Design Architect: Ateliers Jean Nouvel

Architect of Record: Adamson Associates Architects

Structural Engineer: WSP Cantor Seinuk

Height: Orig: 1250 ft. Reduced to 1050 ft. by Dept. of City Planning

MoMA Tower

Designed by the acclaimed French architect Jean Nouvel, the MoMA Tower, which his studio named Tour Verre, successfully made its way through the review process of the City Planning Commission in the summer of 2009, although with a reduction of height from the original proposal for 1,250 ft., which was cut down to 1,050 ft. The project was halted, however, by the severe recession in financial markets that effectively ended all real estate lending. The project has revived in recent months.

The drawings and diagrams at the left, from pubic documents filed in the Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) and submitted as part of the review process of the City Planning Commission, illustrate three variations of the tower: the massing based on compliance with the as-of-right zoning; the building with extra air rights purchased from adjacent properties; and the "Expanded Development Proposal" that added both height and some modest girth to the tower using the additional FAR to increase the size of the floor plates beyond the "sky-exposure plane" of the zoning envelope, thus triggering the public review process.

50 West Street

Expected completion: 2016 (actual completion: 2018)

Developer: Time Equities, Inc.

Sponsor: 50 West Development, LLC

Design Architect: Jahn Archiects

Architect of Record: SLCE

Interior Designer: Thomas Juul Hansen

Structural Engineers: DeSimone Consulting Engineers

MEP Engineers: I.M. Robbins

Height: 783 ft. | 63 floors

G.F.A: 546,000 sq. ft.