RESIDENTIAL RISING: Lower Manhattan since 9/11

THEMES

VIEWS and SLENDERNESS

Views are the reason to build tall. And given New York City's zoning regulations, which limit square feet of floor space, not overall height, the way to construct the most spectacular apartments in the sky is to make floor plates small and stack many of them very high. The photographs and computer renderings here of the topmost floors of three of our featured towers – 8 Spruce Street, 56 Leonard, and 130 William – were created to market apartments, but their sunset and evening views capture the romance of posh penthouse privilege.

Slenderness is a design and development strategy frequently employed for luxury condominiums in New York after about 2009 when the first of the super-slender towers of “Billionaire’s Row” south of Central Park – One57, designed by the French Pritzker Prize architect Christian de Portzamparc – began to rise. Engineers describe a building as “slender" if its height-to-base ratio is at least 1:10 or 1:12.

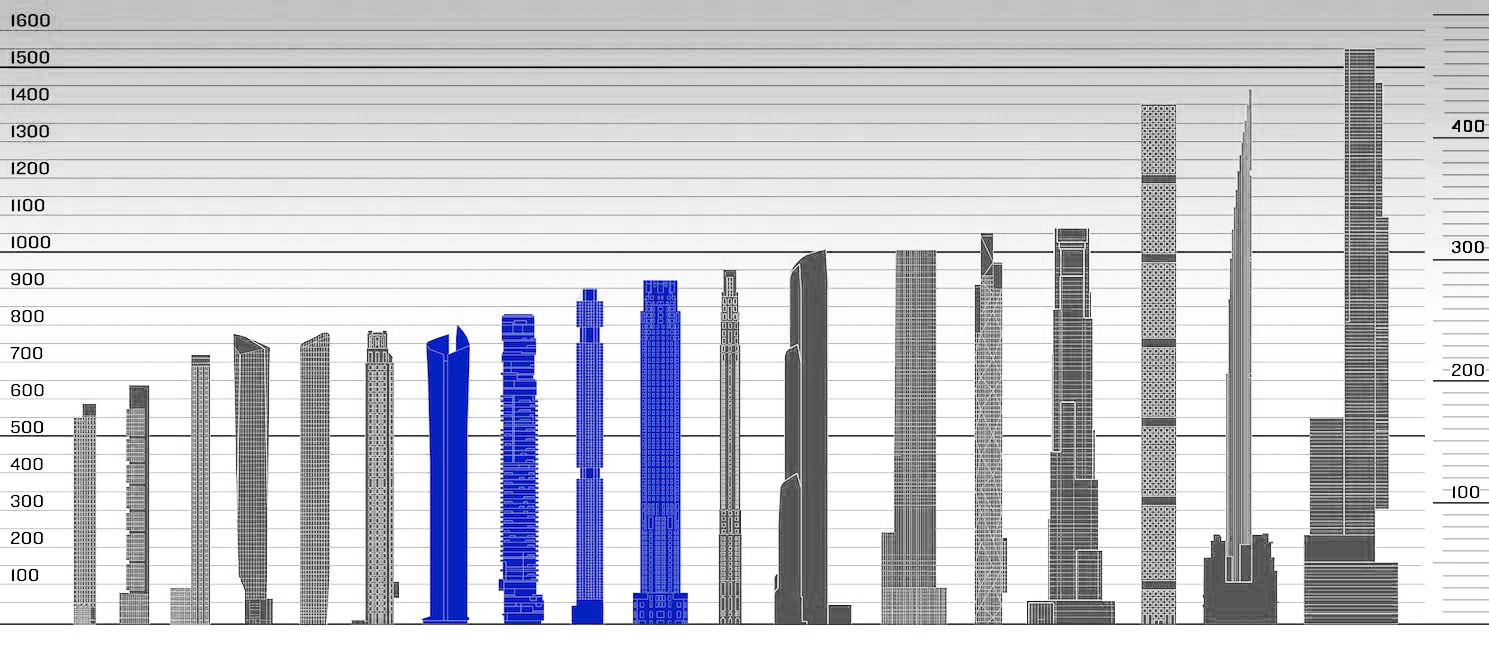

The chart of silhouettes reprises a study The Skyscraper Museum created for its 2013 exhibition SKY HIGH & the Logic of Luxury, which was further developed in an online project titled New York's Super-Slenders. Here, the four Downtown super-slenders in Residential Rising are shown in blue.

Top:

8 Spruce St.

Architect: Frank Gehry, Gehry Partners

Photo courtesy of DBOX

Center:

56 Leonard, cantilevered balcony

Design Architect: Herzog & de Meuron

Photo courtesy of Herzog & de Meuron

Bottom:

130 William

Design Architect: Adjaye Associates

Photo courtesy of Adjaye Associates

In blue, left to right: 111 Murray Street, 56 Leonard, 125 Greenwich Street, and 30 Park Place.

RESIDENTIAL RISES above the COMMERCIAL SKYLINE

This remarkable digital rendering by the creative communications company DBOX was made to market the condominium tower 25 Park Row, which is placed at the center of the image. It was part of a campaign to promote the project in the media and on the project’s website, as well as in the sales suite where the model, shown here without its larger base including City Hall Park, was displayed.

The rendering pictures a twilight view with a light-filled blue sky, but with the park trees in shadow and the cupola of the 1812 City Hall illuminated. It shows many of the residential towers featured in the exhibition and clarifies how they have surpassed the scale of the office buildings of past decades.

STARCHITECTS

The term “starchitects” – internationally-recognized designers whose names carry caché and add value to projects – preceded 2001, but their rise in New York residential real estate connects directly to the aftermath of 9/11 and the immense attention given to issues of architectural design in the rebuilding at Ground Zero. The media focus and the public emotion trained on questions about a master plan for the arrangement of both the commercial buildings on the World Trade Center site and the design of the Memorial and Museum forced an open process of architectural competitions and alternative proposals that kept architects center stage for at least two years after 9/11.

In the press and the profession, starchitects were generally defined by winning competitions, international prizes, and prestige commissions for cultural institutions. The most coveted prize was to be named the annual Pritzker Laureate. Frank Gehry won the Pritzker in 1989 and the partners Herzog and de Meuron received the award in 2001. The French architects Christian de Portzamparc and Jean Nouvel, both of whom designed super-slender condo towers in Midtown, won the Pritzker in 1994 and 2008, respectively.

Downtown, two buildings stand out as dramatic experiments in skyscraper design, Gehry’s 8 Spruce Street and 56 Leonard by Herzog and de Meuron. Both architects played with form, silhouette, materials, and surface in a way that would make most New York developers and construction managers nervous. But Forest City Ratner and Alexico stayed the course and brought their projects to market even through the banking crisis and Great Recession of 2008 and marketed their properties as bold design statements. Similarly, Sir David Adjaye, acclaimed for his design of the National Museum of African American History and Culture, was brought on to 130 William Street to fashion a distinctive façade and brand the marketing effort.

Other internationally-recognized architects commissioned to create Downtown icons were Helmut Jahn at 50 West Street, Rafael Viñoly at 125 Greenwich, and Robert A.M. Stern for 30 Park Place, as well as KPF at 111 Murray. Skyscraper specialists Pelli Clarke Pelli and COOKFOX designed contextual towers in Battery Park City and at 25 Park Row.

TOP LEFT:

56 Leonard in Tribeca

Design Architect: Herzog & de Meuron

Photo courtesy of Herzog & de Meuron

TOP RIGHT:

130 William

Design Architect: Adjaye Associates

Photo courtesy of Adjaye Associates

BOTTOM LEFT:

8 Spruce St.

Architect: Frank Gehry, Gehry Partners

Photo by © Marshall Gerometta

BOTTOM RIGHT:

50 West St.

Architect: Helmut Jahn

Photo: Rainer Viertlböck, Courtesy of Jahn

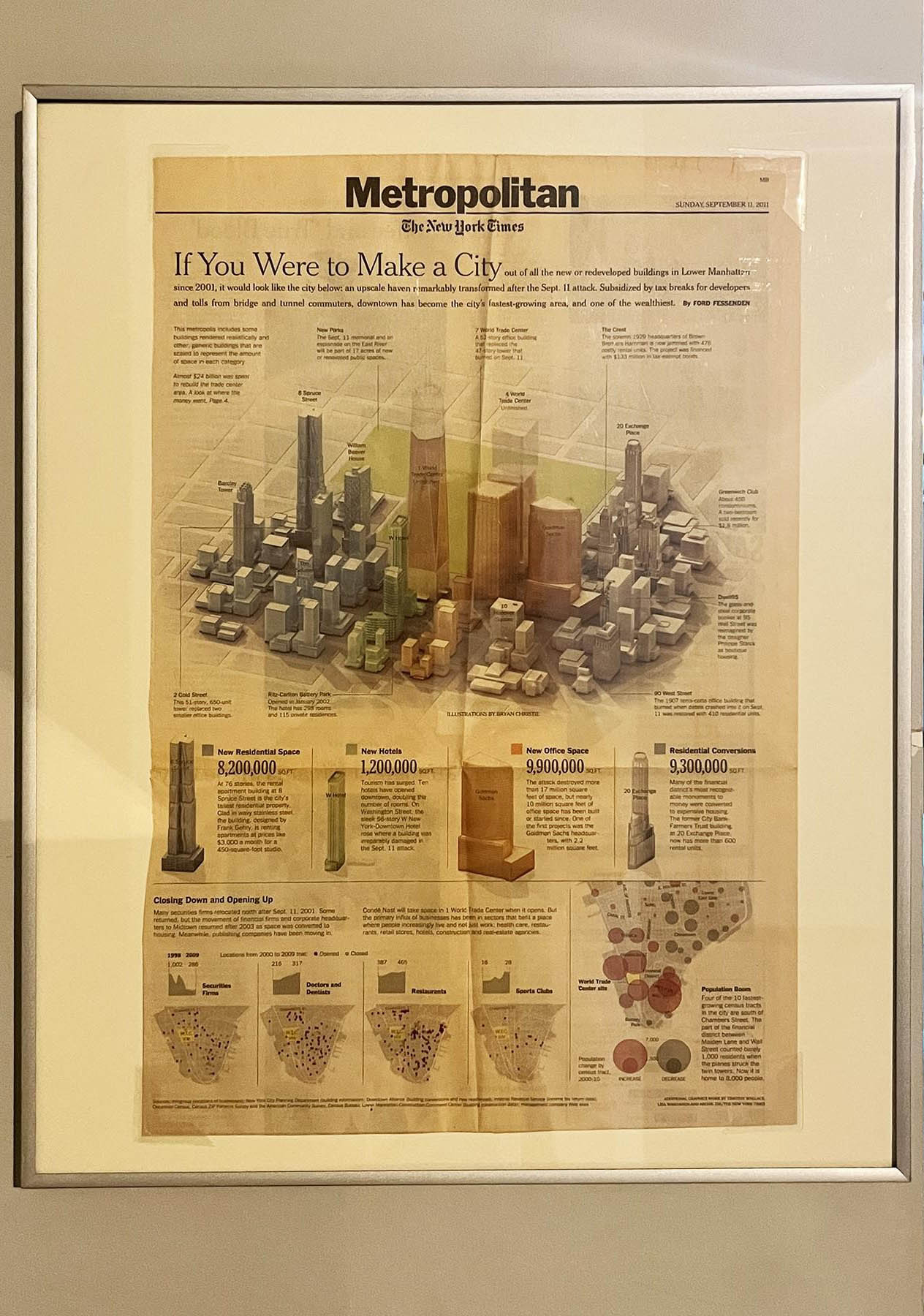

IN THE FIRST DECADE

This discolored clipping from The New York Times special section called “The Reckoning: America and the World a Decade after 9/11,” published on the tenth anniversary of the attacks, draws together in one image representations of all new construction and conversions downtown during the decade, organized by type: office space; hotels; new residential and existing office buildings converted to residential use. The tallies of square feet in each category show that converted office space outpaced new residential construction and that the total of residential space was double that of new office space – which at only 9.9 million square feet represented hardly more than half of the 17 million square feet destroyed. As the caption notes, “subsidized by tax breaks for developers and bridge and tunnel fares from commuters, downtown has been the fastest-growing neighborhood.”

Collection of The Skyscraper Museum

CONVERSIONS

Since 2001, nearly 60 office buildings in lower Manhattan have been converted to residential use, creating around 12,000 dwelling units, according to surveys by the Downtown Alliance. These are of two types with respect to development strategy: landmark properties and average older buildings.

The impetus to convert Downtown’s older office buildings to residential use began in the mid-1990s for a host of reasons. The stock market crash of 1987 and the savings-and-loan crisis brought a recession to New York commercial real estate markets that by mid-decade had produced a vacancy rate above 30 percent and left 25 million sf. of office space unrented. The City tried to address these problems with public policy initiatives. In 1993, the Dinkins Administration and the Department of City Planning issued a plan that called for Downtown’s reinvention as a more diversified “24/7” neighborhood. In 1994, the new Giuliani Administration and its Chairman of the Planning Commission Joseph Rose advanced a package of economic and regulatory incentives that encouraged reinvestments in older buildings, including a 14-year abatement on property taxes for office buildings converted to apartments and zoning changes that legalized “live-work” spaces like those in Soho and Tribeca.

Before the late Nineties, owners of commercial real estate had strongly opposed the strict regulations connected to landmark status. But generous federal historic-preservation tax credits were available for buildings that were designated landmarks or placed on the National Register – a financing opportunity that helped to soften their resistance to regulation. From 1994 to 2001, under the Chairmanship of Jennifer Raab, the Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) designated 24 individual landmarks, 17 of which were skyscrapers of the 1910s to 1930s, mostly in the Financial District, as well as the Stone Street historic district.

TOP LEFT:

70 Pine St.

Architect: Clinton & Russell, Holton & George, 1932

Converted by Rose Associates, 2015

TOP RIGHT:

One Wall St.

Original Architect: Ralph Walker, 1930

Converted by Macklowe Properties

BOTTOM LEFT:

Woolworth Tower

Original Architect: Cass Gilbert, 1913

Converted by Alchemy Properties

BOTTOM RIGHT:

90 West St.

Architect: Cass Gilbert, 1907

Converted by The Kibel Company, 2005

TWO SIDES OF THE COIN, 2002

The framed newspaper article and poster map date from 2002 and attest to massive efforts of government to protect businesses, buildings, and people directly affected by the cataclysmic collapse of the Twin Towers. As John Holusha wrote in The New York Times of May 19, 2002:

“To help revive the downtown office market in the wake of the Sept. 11 attack, a complex set of federal, state and city incentives - cash allowances and tax breaks - are being offered to businesses that renew leases or move into the area.”

The article focused only on office space and reported that the incentives, together with reduced rents after the attack, lowered the cost of office space to 40 to 45 percent of Midtown.” There were also subsidies to companies for retaining or attracting new employees, as well as many other programs.

These thumbs on the scales began to cause alarm among preservation and civic groups who feared that too-rapid redevelopment would threaten Downtown’s historic urban fabric. Five organizations formed a coalition to “protect the distinctive texture, rhythm, and scale” of several streetscapes they believed were endangered by “overzealous economic and neighborhood revitalization efforts.” The poster and map present three neighborhoods, or “Corridors of Concern,” they believe merited protection: Fulton, Greenwich, and West streets.

BEFORE 9/11

This highly-detailed, hand-carved miniature wooden model of Downtown Manhattan was donated to The Skyscraper Museum by devoted amateur model maker and Arizona resident Mike Chesko. The 35 x 29” model presents the skyscrapers of Downtown in a 1:3,200 scale; each inch of the model represents about 267 feet at full scale, so the Twin Towers stand 5.1 inches tall. The model represents Lower Manhattan in 2000, before the Twin Towers were destroyed by terrorists on September 11, 2001.