The Museum's October 2013 through June 2014 exhibition SKY HIGH & the logic of luxury was documented in an online version that was hard-coded and buggy. All the content of that site is transferred here on a new platform, but without changing tenses from present to past.

THE HISTORY OF SLENDERNESS

New York City is the birthplace of the improbably slender tower. In the late 19th- and early 20th century, many tall shafts rose over every square foot of their narrow, high-priced lots. Indeed, it was the high value of the land and the potential offered by the technology of the elevator and steel-cage construction to pile many floors of rentable space onto a small lot that made New York a city of towers.

The first was a period of skyrocketing growth when, until the passage of the city's first zoning law in 1916, no municipal regulations constrained height. By 1909, the Metropolitan Life Insurance Tower rose 700 feet-- 50 stories-- on a lot only 75 x 85 feet.

A second phase of vertical ambition and energy came in the 1920s. Shaped by the massing formula set by the 1916

zoning law, buildings with bulky pyramidal bases and slender soaring towers, covering no more than 25 percent of the lot area, became the new characteristic type of New York skyscrapers.

After 1961, a new zoning law set a limit on building height-- or more accurately, imposed a maximum total floor area permitted on a given lot. By allowing for the purchase and transfer of "air rights," however, the code created the opportunity for some buildings to grow taller, and in the case of residential towers, encouraged slenderness.

This exhibition proposes that we have entered a fourth phase of a special form of slenderness: the super-slim residential skyscraper.

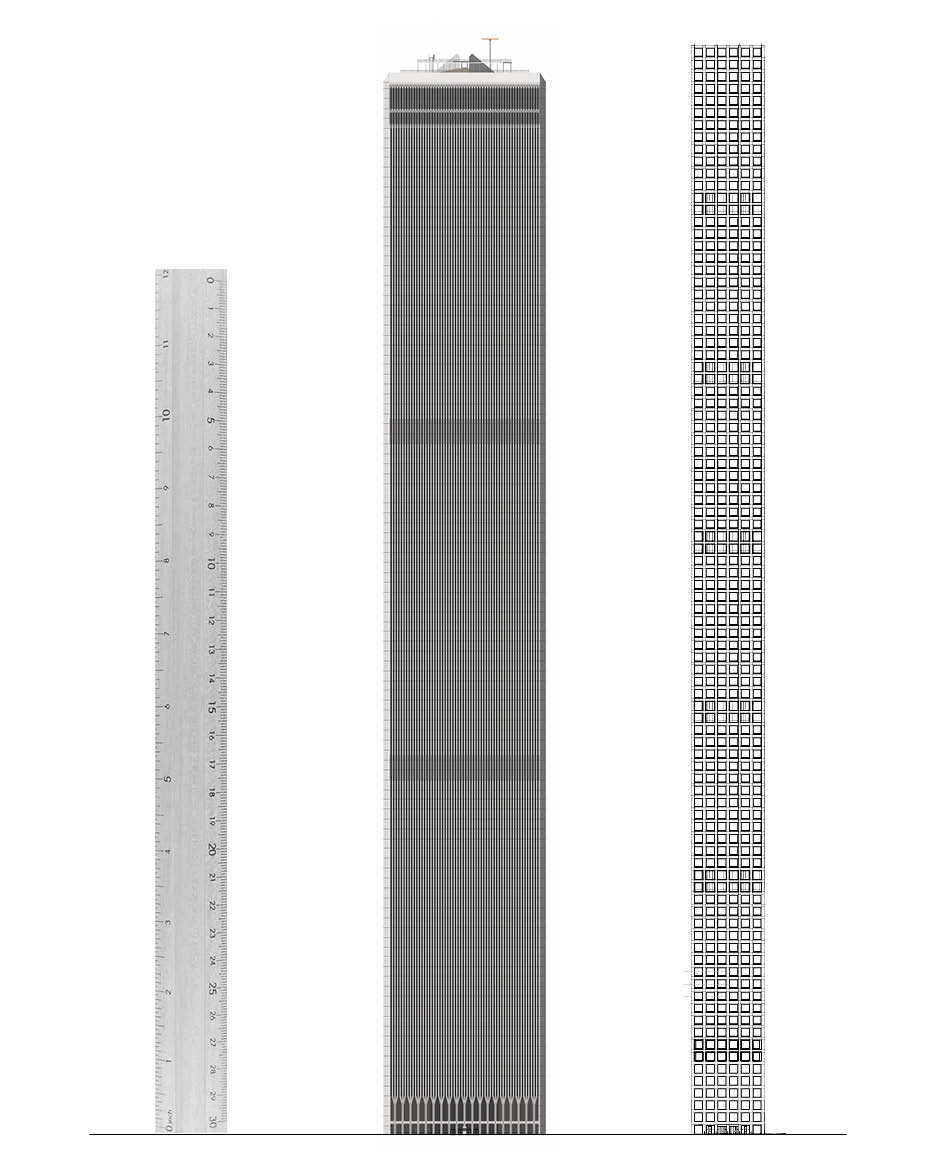

Image: The Skyscraper Museum

Tall, but not Slender

The World Trade Center North Tower was the tallest building in the world on its completion in 1971. But at a height of 1,368 ft. and with a big square floor plate, 209 feet on each side, the ratio of its base to height was less than 1:7.

"Slenderness" is an engineering definition. Structural engineers generally consider skyscrapers with a minimum 1:10 or 1:12 ratio - the width of the building's base to its height - to be "slender." Slender towers require special measures to counteract the exaggerated forces of wind on the vertical cantilever. These can include additional structure to stiffen the building or various types of dampers to counteract sway.

The image above compares at the same scale the former 1 WTC and the residential tower 432 Park Avenue, now under construction. The base of the apartment building is 93 feet square, and the shaft will rise to 1,398 feet, making its slenderness ratio 1:15. To visualize a 1:12 ratio, we show a ruler 1-inch wide and set on end.

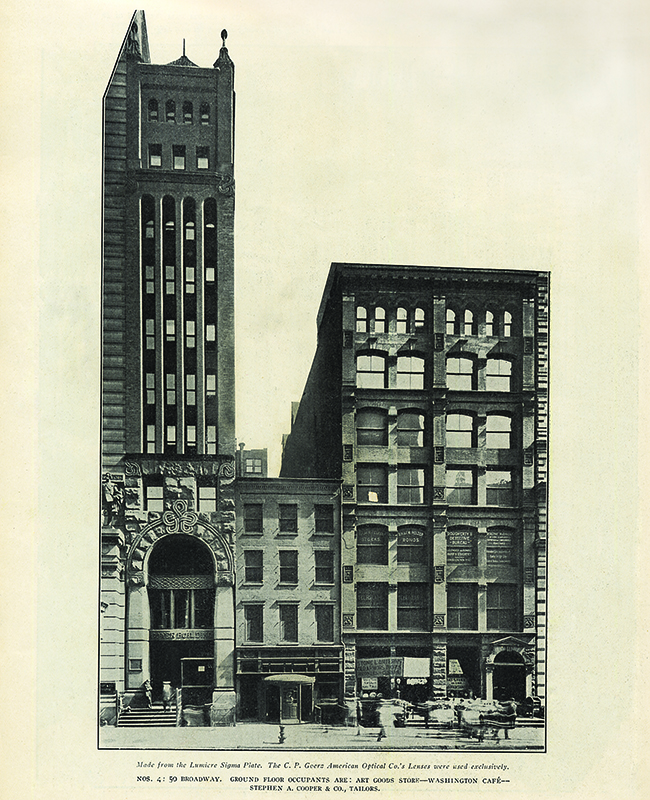

Tower Building, c.1909, Both Sides Broadway (1909) Collection of The Skyscraper Museum.

Tower Building

Slenderness in commercial architecture depends on engineering technology. Masonry construction is more suited to pyramids, and medieval cathedrals demonstrated the limits of stone 700 years earlier. In the late 19th century, to create a tall urban building on a small or narrow, high-priced lot, it was necessary to employ the new technology of steel-cage construction. As Chicago engineers and architects had demonstrated in their city since 1884, steel skeletons created more open (rentable) area on every floor and allowed for larger expanses of windows.

The first tall building in New York to use metal-cage construction was the Tower Building at 50 Broadway (demolished 1914), designed by architect Bradford Lee Gilbert and completed in 1889. At 11 stories, it was not the tallest in the city, but with a frontage on Broadway of a mere 21.5 feet, it was extremely slender for its height. The novelty of its metal-cage construction was the subject of considerable attention in the popular press, as pundits predicted its collapse.

The NYC Building Code did not explicitly allow for skeleton-frame construction until 1892, but the Department of Buildings approved Gilbert's individual application. As author and engineer Donald Friedman explains, the Tower Building had a hybrid structural system: "the side walls were bearing at the top four levels of steel framing, but were carried below that point on a frame consisting of wrought-iron beams and cast-iron columns. In other words, the Tower Building was, structurally, a four-story bearing-wall building sitting on top of a seven-story skeleton frame. The overall building was noticeably slender and the weight of the bearing-wall structure at the top probably helped the frame below perform: cast-iron columns cannot handle tension well, and the weight of the upper-floor masonry served as a pre-stressing compression load in the columns below."

Gillender Building, 1900, New York. Detroit Publishing, Co., Library of Congress.

Gillender Building

When the Gillender Building was completed in 1897, it was the fourth tallest building in the city, measuring 306 feet to the tip of its spire. What was most remarkable about it, though, was its slenderness. On the tiny site of the 6-story Union Building, on the northwest corner of Wall and Nassau streets, architects Berg and Clark packed 20 stories on a plot of only 26 x 73 feet.

Just five feet wider than the Tower Building, but nearly twice as tall, the Gillender Building employed a complete steel-skeleton frame that made its extreme slenderness possible. By 1897, true skeleton-frame buildings had been constructed for several years, and the technology was rapidly maturing. The use of built-up steel columns to carry the heavy gravity and wind loads, multiple spandrel beams to support the exterior walls, and wind bracing within the frame had become standard.

It was the extraordinary value of the land at the prominent corner of Wall, Broad, and Nassau streets - the heart of capitalism, with the New York Stock Exchange, the headquarters of J.P. Morgan, the U.S. Sub-Treasury, and numerous banks - that made the enormous expense of the tiny, ornate Gillender Building both possible and profitable. The high demand for this prime location, combined with advances in steel-frame technology, drove developers and architects to capitalize on the escalating value of land in super-slender towers.

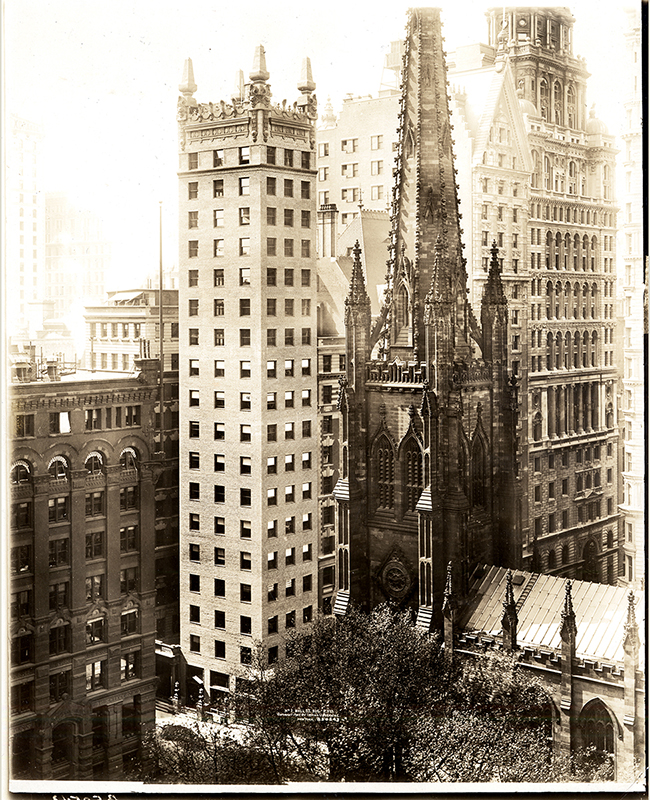

Photograph of 1 Wall Street, 1908 Collection of The Skyscraper Museum

1 Wall Street

The implied status of the address "1 Wall Street" certainly inspired the 18-story height, if not the architectural quality, of the speculative office tower nicknamed the "Chimney Building." In 1905, the 30' by 40' lot that had been occupied since the early 19th century by a four-story commercial building changed hands for the highest price per square foot ever recorded for Manhattan property ($615 psf). The new owners were business investors from St. Louis, who erected a very plain tower as a rental property. The tower squeezed two offices per floor onto the 1,200 sq. ft. parcel (an area about one third the size of this gallery).

Changes to the New York City Building Code between 1892 and 1901, coupled with the increasing level of experience with curtain walls within the design and construction community made towers such as 1 Wall Street possible. By the time of the Chimney Building, 12-inch walls had become common. Thinner walls created more usable interior space, reduced the weight on the steel frame, and reduced the possibility that the walls might accidentally carry structural load meant for the frame. On the other hand, thinner, weaker walls had less structural capacity to carry the projecting ornamentation of the American Renaissance style that had become popular in the 1890s.

In 1928, the powerful interests of the Irving Trust Company purchased 1 Wall Street and the neighboring buildings to the corner of New Street. In 1929 construction began on the 50-story Art Deco masterwork designed by Ralph Walker of the architectural firm of Voorhees, Gmelin & Walker, that still graces the corner today.

Singer Building, c. 1908, Library of Congress.

Singer Tower

Rising to 612 feet, the 47-story Singer Tower was the tallest building in the world when it was completed in 1908. Designed as a corporate headquarters for successful Singer Manufacturing Company, the tower represented the boldest expression to date of New York's ambitious vertical construction, overtopping the turn-of-the-century record holder, the neighboring 15 Park Row, by more than 225 feet.

Architect Ernest Flagg, who had designed the two earlier buildings on the property for the company, combined the existing structures to create a 14-story uniform base upon which a 35-floor tower would rise. His slender shaft of red brick and bluestone in the "modern French" style amazed architectural critics, including Montgomery Schuyler, who judged the Singer Tower "among the most interesting of our experiments in skyscraping."

Previously known as an outspoken critic of tall buildings, the Beaux-Arts trained Flagg defended his design as a model for skyscraper reform. The future city, as he envisioned it, would be composed of buildings with thin, campanile-like towers limited to one-quarter of the area of the site. Thus, lower office blocks would combine to create an ordered urban ensemble, but the isolated towers-memorable, unique, and artfully disposed-would present a freer arrangement of a "picturesque, interesting, and beautiful" skyline with a European flavor.

In 1968, the Singer Tower became the tallest building ever demolished as both Singer and its neighboring City Investing Company Building made way for the U.S. Steel Building, now known as 1 Liberty Plaza.

Metropolitan Life Insurance Tower, Madison Square, New York. Detroit Publishing Co. Library of Congress

Metropolitan Life Tower

Soaring to 700 feet, the Metropolitan Life Insurance Tower took the title of world's tallest office building from the 612-foot Singer Tower in 1909, soon after the company became the world's largest insurer. Designed by architect Napoleon LeBrun and Sons, the 50-story building took the form of a slender shaft modeled on the Renaissance bell tower of San Marco in Venice.

In the late 1880s, the company sold its building in Lower Manhattan and moved uptown to Madison Square and 23rd Street, where it erected an 11-story headquarters, completed in 1893. The rapid growth of the business required more and more space for burgeoning staff and files, and over next decade, annexes were added until the buildings covered nearly the entire block. After acquiring the last remaining parcel and demolishing the Madison Square Presbyterian Church, the company erected its signature campanile as a symbol of its success.

The decision to construct a tower of 700 feet on a site just 75 by 85 feet may have been an extravagance, but the skyscraper was also an income-generating property. In a report to his board, Vice President Haley Fiske called the structure "a proper investment of the company's funds, that didn't coast it a cent, because the tenants footed the bill."

Faced in expensive Tuckahoe marble, in the 1960s, the tower was subjected to an aggressive remodeling campaign in which most of the classical detail was stripped off, as well as the balconies and a prominent cornice. The marble façade was replaced with sheer limestone panels, so the tower would match the modernized base. Today, the clock faces remain the only memory of the ornate façade.

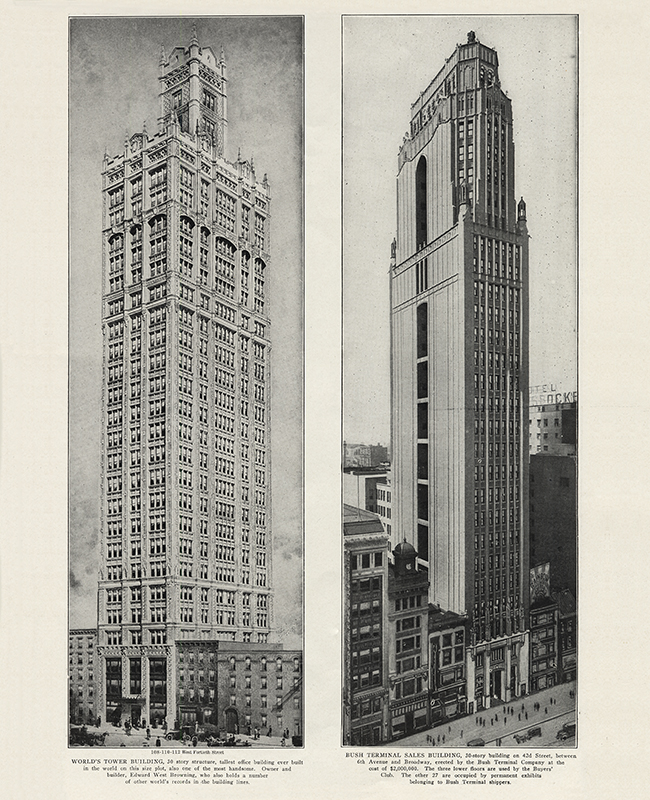

World Tower Building and Bush Terminal Sales Building. King's Views of New York, 1926. Collection of Gail Fenske

World Tower & Bush Building

By the 1910s, rampant high-rise development was overtaking much of Manhattan, advancing north up the spine of Broadway, beyond Union Square and Ladies Mile into the newly named Times Square at 42nd Street. On cross streets, especially in the 20s and 30s, speculators constructed block upon block of high-rises that leased space for offices, showrooms, and light manufacturing.

The contemporary World Tower and the Bush Terminal Sales Building were extreme examples of tall and slender commercial properties erected by colorful entrepreneurs of the period. Both stacked thirty stories on lots less than 60 ft. wide, and the World Tower Building at 110 W. 40th St., completed in 1915, was trumpeted as "one of the highest buildings in the world on so small a plot of ground." The developer Edward West Browning indulged in rich white terra-cotta ornament, as well as the windows on all four sides of the World Tower, making it a standout among the more utilitarian lofts of the Garment District.

Erected in 1917 by Irving T. Bush, the businessman who created the massive Bush Terminal warehouse and factory complex in Brooklyn, the Bush Terminal Sales Building at 130 W. 42nd St. was one of the last of the tall towers to rise without the setbacks the 1916 zoning law required. Its architect Harvey Wiley Corbett was a leading advocate of the setback form, but he was happy to oblige his client with a slender tower of stacked showroom floors that imitated a Gothic spire.

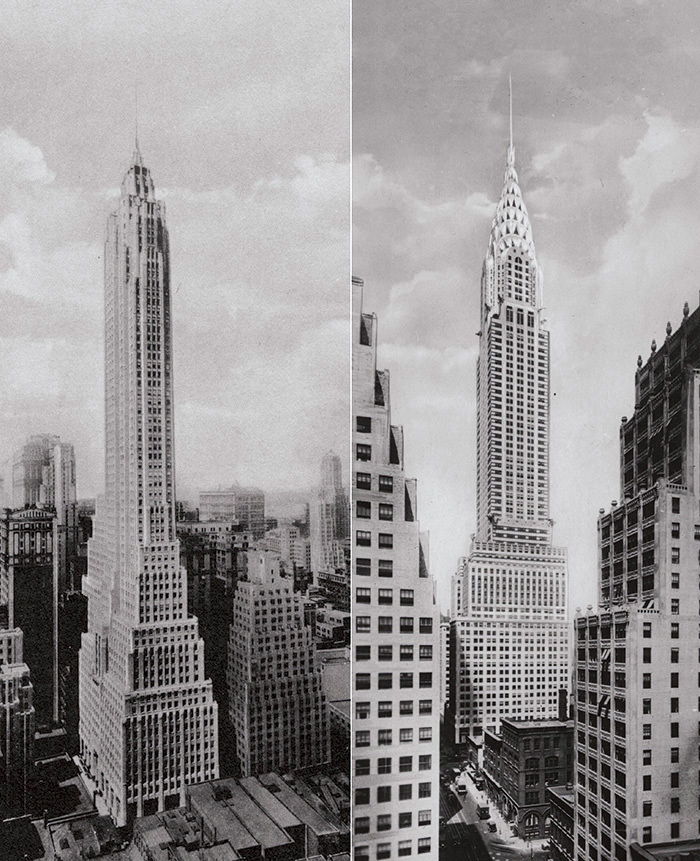

Left: Cities Service Building, 1930s. Collection of the Skyscraper Museum; Right: Chrysler Building, 1930s. Collection of The Skycraper Museum

1916 Zoning and 25 Percent Towers

New York began to regulate skyscraper form in 1916 when the city passed America's first comprehensive zoning law. The regulations mandated multiple setbacks on the bases of tall buildings that would protect a measure of sunlight on the street, and it established a template for a maximum mass or "envelope" that a building could fill. Developers, of course, sought to exploit every available square foot of rentable space, so their buildings expanded into the full template.

In addition, the 1916 law allowed for a tower of unlimited height to rise above 25 percent of the center of the lot. Buildings on large sites could thus take advantage of the opportunity to add a slender tower atop the pyramidal base. As the photographs of the slender spires of the Cities Service Building at 70 Pine Street and the Chrysler Building illustrate, it was the zoning law-even more than individual architects-shaped the characteristic setback massing of high-rises across Manhattan.

Hotels on Central Park, 1930s. Collection of the Skyscraper Museum

Hotels of the 1920s

The swank hotels that lined Fifth Avenue at the southeast corner of Central Park - from left to right, the Pierre (1930) , Sherry Netherland (1927), and the Savoy-Plaza (1927, demolished in 1964), and the pointed top of the Ritz (1925) in the distance -- illustrate both the enduring attraction of park views in the luxury life of New York and a characteristic form for the 1920s-type of skyscraper hotel, a high pyramidal base surmounted by a slender tower.

Because the 1916 zoning law applied to commercial buildings, and hotels fall into the commercial-use category, hotels were able to develop a 25 percent tower just like office buildings. By contrast, apartment buildings were regulated by the tenement laws which generally capped height at 90 ft., so that hotels were the only form of residential high-rise until the Multiple Dwelling Law of 1929. The stone-faced tower of the Pierre and the romantic French Renaissance silhouette of the Sherry Netherland associated their high-class clientele, including some long-term residents in apartments, with the tradition of historical styles rather than the Art Deco modernism just coming into popularity at the time.

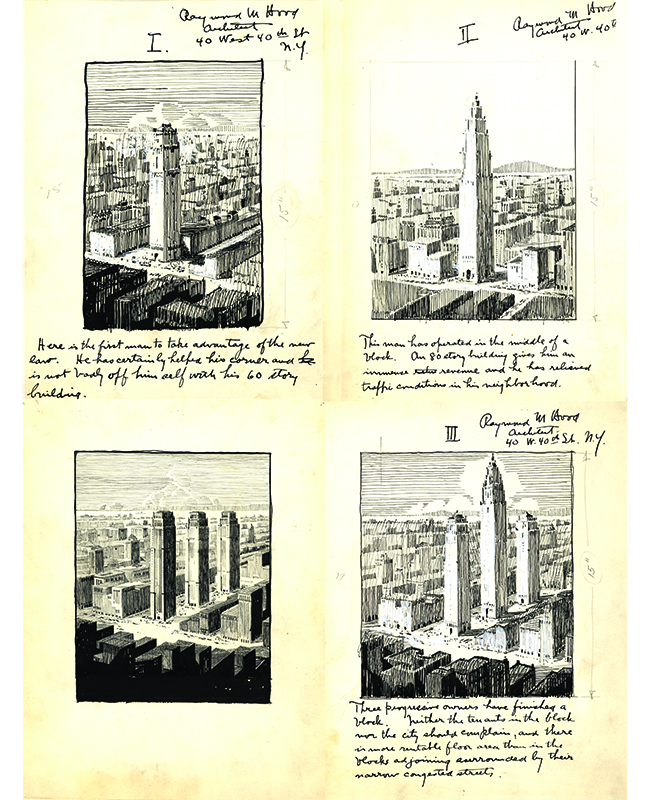

Sketches by Raymond Hood for "Tower City Aerial Perspective," I, II and III. Courtesy Architectural Archives, University of Pennsylvania.

City of Towers

In the late 1920s, the prominent architect Raymond Hood presented a concept for how to transform New York into a city of slender towers and expansive open spaces-what he called a "modern city of sunlight, air, and free circulation." Hood first articulated his proposal in 1924 in a New York Times article, "City of Needles," and he continued to promote the concept in numerous forums in 1926-1929 in response to the contemporary debate among New York architects and planners over the issue of skyscrapers and traffic congestion.

In the series of pen-and-ink drawings shown here, prepared for a magazine article entitled "Tower Buildings and Wider Streets," Hood outlined his idea for the gradual replacement of dense block coverage with tall, slender towers surrounded by greatly enlarged areas for traffic circulation. Fundamentally altered, New York's historic grid would be replaced by a pattern of two or three towers per block.

To accomplish this transformation, Hood proposed creating incentives for developers to build on a smaller percentage of their lots. Anticipating, in a way, the bonus FAR for open space of New York's 1961 zoning law, Hood proposed a formula that would relate building volume to street frontage and allow taller towers for structures set back from the lot line. Stressing practicality, Hood believed his plan would benefit all parties: increased volume (and rentable space) for the developer; more light and air for the towers' occupants; and more street space for the public.

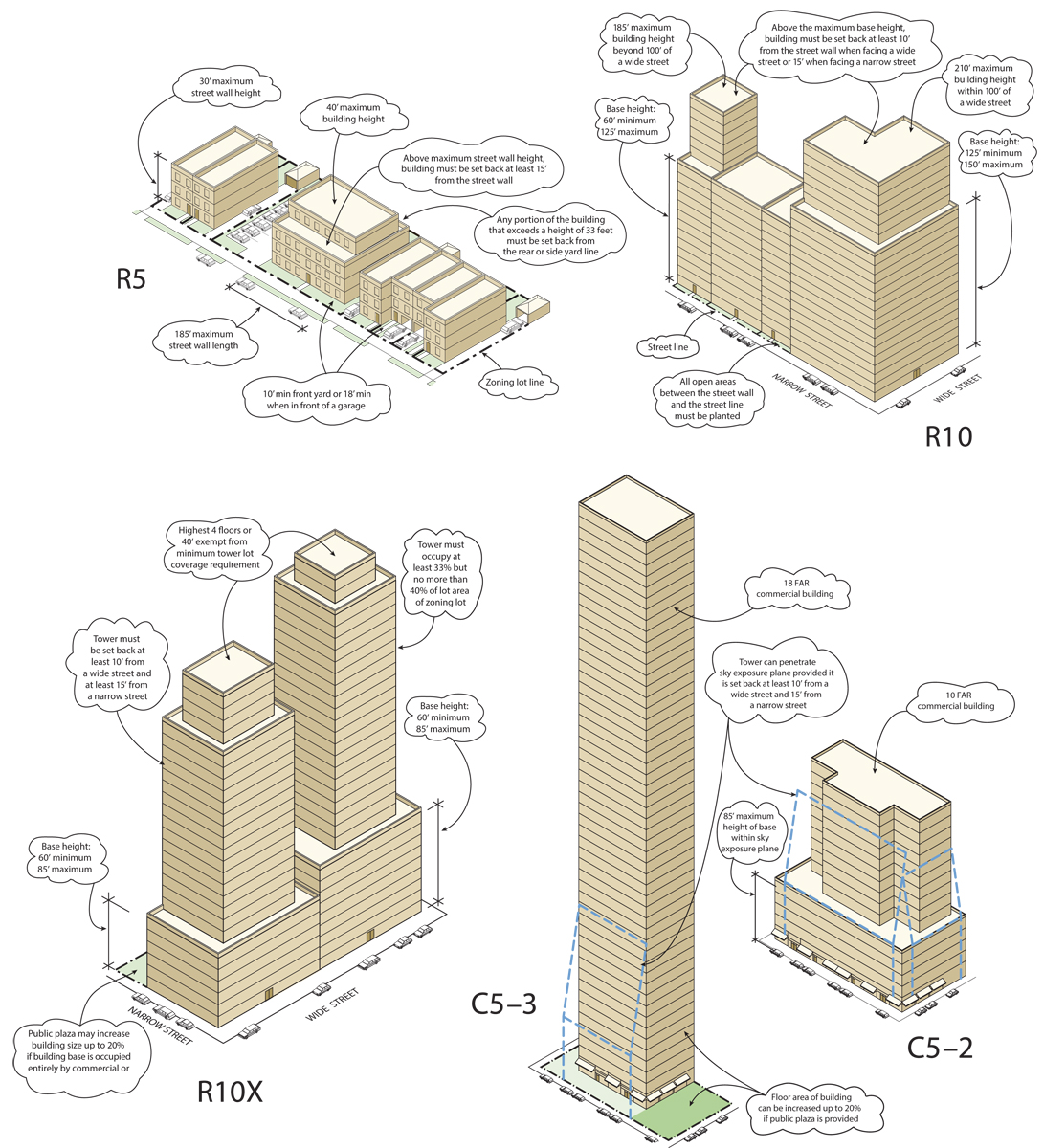

"NYC Zoning District Diagrams." https://www.nyc.gov/html/dcp/pdf/zone/zoning_handbook/c5.pdf. New York City Department of City Planning.

1961 Zoning and FAR

In 1961, New York City passed a new zoning law that dramatically reduced the height and bulk previously allowed under the 1916 zoning formula. Instead, it set a maximum amount of space that a property owner could build within the footprint of his lot. This formula, known as the Floor Area Ratio (FAR), is the square-foot area of the lot, multiplied by a number for that zone, such as 6, 10, or 15, that equals the maximum number of square feet of floor area that can be arranged and stacked within the footprint of the lot.

The FAR formula is applicable to all types of structures and applied to all districts–Residential, Commercial, and Manufacturing. The diagrams shown here, compiled from the current zoning primer, available on line on the website of the NYC Department of City Planning, illustrate several formulas for residential zones.

While the developer is allowed to arrange the FAR on the site however he prefers, the new law also offered incentives to create open space around buildings by allowing bonus FAR for new construction that created plazas or other public access at street level. This bonus encouraged the modernist expression of a sheer, slab-like tower rising in an open plaza for both office and residential towers. As Robert A.M. Stern observed in New York 1960: "The passage of the new zoning was postwar New York’s pivotal architectural event, irrevocably changing the relationship between buildings and streets that had prevailed for over three hundred years."

Another important provision of the 1961 law was the ability to sell and transfer of unused FAR, or "air rights," to an adjacent property.

Left: Trump Tower, 1983.

Right: Trump World Tower, 2001.

Courtesy of Trump Organisation.

Trump Towers

The history of luxury condominiums in New York City can be traced back to the mid-1970s when mixed-use skyscrapers such as Olympic Tower on Fifth Avenue and 52nd St. proved the appeal of new locations for high-end, high-rise residences. The dark tinted-glass curtain wall was a material and stylistic vocabulary popularized in office towers like the Seagram Building. Developer Donald Trump adopted the bronzed look for his first signature tower on the Fifth Avenue just south of 57th St., completed in 1983, in which architect Der Scutt used a faceted, sawtooth facade that minimized the tower's bulk and created more "corner offices" on the floors below and directed views in the condominiums on floors 30 to 58.

In 2001, Trump added another sleek glass prism to his portfolio: Trump World Tower, which at 861 ft. became the then-tallest residential building in the city. In order to stretch as high as possible, Trump shrewdly amassed the unused air rights from surrounding buildings, including two brownstones, the Holy Family Church, and the Japan Society. Architect Costas Kondylis designed the tower as a slender slab of with a taut dark curtain wall that projected a minimalist sensibility. The large expanse of glass and overall slenderness resulted in the decision of the engineers WSP Cantor Seinuk to include a tuned mass damper at the top of the tower to counteract sway, the first such application in a residential building.

Metropolitan Tower, c.1987 Courtesy of Macklowe Properties

Metropolitan Tower

This pair of photographs of the Metropolitan Tower, a luxury condominium developed by Harry Macklowe in the late 1980s, seen both under construction and completed, clad in Darth-Vader black glass, illustrates two key characteristics of the period that continue today. First, reinforced concrete is the preferred material for residential buildings, in contrast to the use of steel in office towers. Second, 57th Street emerged as a prime location for international luxury.

The slenderness of the Metropolitan Tower comes from its triangular wedge shape that rises sheer and high, angling its hypotenuse at the view of Central Park. The building's entrance fronts on 57th Street, two doors east of Carnegie Hall and in the middle of a block of boutique shopping and posh hotels and restaurants. In today's new generation of ultra-luxury towers, 57th Street has a special attraction and has been dubbed by some wags "The Avenue of the Oligarchs."

Left: Trump Palace, 1991. The Architecture of Frank Williams (1997). Collection of the Skyscraper Museum; Right: 515 Park Ave, 2000. Photo by Jeff Goldberg/ESTO. Courtesy of Zeckendorf.

Traditional & Postmodern

During the same years the modernist dark-glass curtain wall set the standard for luxury towers, a counter style appeared that emphasized traditional values and materials, sometimes even in the portfolio of the same developer. The two buildings pictured here, Trump Palace (left) and 515 Park Avenue, represent two aspects of postmodern or classical styles, both by the late architect Frank Williams.

Completed in 1991 and 2001, the slender spires of Trump Palace and 515 Park Avenue, developed by the Zeckendorf family, evoked the towered hotels of the 1920s. Both employed a pattern of masonry walls and picture windows that create more traditional interiors than all-glass facades and also hide structural columns within the walls. The wrap-around corner windows and pyramidal crown of Trump Palace allude to Art Deco favorites such as the Chrysler Building and Majestic Apartments, while the corner quoins, pilasters, and balconies, used at 515 Park Avenue, complement the walls of French limestone. In both buildings slenderness served as a strategy to lift the upper floors high into the sky to capture panoramic views and keep the floor plates relatively small and more exclusive.

In 1991, the most expensive apartment in Trump Palace sold for $3.5 million. According to an October 2013 article in the New York Times, a floor-through combination unit at the Trump Palace, No. 47A/B, "with six terraces and gravity-defying vistas of the cityscape and Central Park" sold for $15 million. Even before its completion in 2001, all of the apartments at 515 Park had been sold, and the building was reported to be the first condominium in the city to achieve $3,000 a square foot.

Left: 80 South St, never built. Courtesy of Sciame Development Inc.

Right: One Madison Park, Courtesy of Cetra/Ruddy Architects, PLLC

Cubes

After 9/11, the idea of conspicuous height was for a while eclipsed, but the perennial appeal of spectacular views was impossible to suppress for long. In 2004, the builder and developer Frank Sciame commissioned architect and engineer Santiago Calatrava to design a slender tower at 80 South St., just outside of the South Street Seaport historic district boundary. Calatrava conceived a scheme for a 835-foot vertical structure that stacked 12 "townhouses in the sky." With only 175,000 square feet of floor area, the tower was very narrow, with a slenderness ratio of more than 21:1. Each of the superimposed cubes was to be an individual dwelling of multiple floors, with private balconies and rooftop terraces. The design was expensive and failed to find attract enough investors in individual units to find the financing to move forward.

Another building, One Madison Park, which has been recently renamed One Madison by its new owner/ developer, employed a similar concept of stacked cubes, differentiated from the dark shaft by white glass and cut into segments that also created wrap-around terraces for some apartments. Designed by Cetra Ruddy with structural engineering by WSP Cantor Seinuk, the 50-story tower rose 621 feet tall on a 50-foot lot, producing a slenderness ratio of 1:12. Largely completed in 2009, the project hit the market at the beginning of the recession, and the first developers had to declare bankruptcy and sell the building.

Highcliff and the Summit, 2003, courtesy of Colin Hamilton

Hong Kong Slenderness

Slenderness is a defining characteristic of Hong Kong's tall buildings, and the city has more pencil-thin towers than any place in the world. In particular, in the 1980's, Hong Kong's high land values and liberal zoning laws spawned many districts of extraordinarily slender and densely-packed apartment towers such as the famous Mid-levels, where hundreds of speculatively-developed apartment buildings exploited the city's permissible maximum FAR of 1:18. Hong Kong apartment units are tiny compared to New York, and the crowding together makes for an extreme density of population, but those conditions are mitigated by the large preserved areas of natural landscape that cover the mountainsides.

The most slender residential skyscraper in the world today is still Hong Kong's Highcliff, a 72-story tower completed in 2003. Designed by the Hong Kong architect Dennis Lau of DLN Architects and Engineers, with structural engineering by the Seattle-based firm of Magnusson Klemencic Associates, it rises 828 feet (252 meters) with an extraordinary slenderness ratio of 1:20.

Princess Tower, Sarah Ackerman (Flickr), June 2013

Dubai Slenderness

Slenderness is a common feature of the residential towers of Dubai, the Middle East Emirate that is also home to the Burj Khalifa, at 2,717 feet (828 meters), the world's tallest building. Dubai developers often cluster their towers very close together–not for lack of space, but to create an instant urban concentration around an attraction or amenity. In this photograph, eight 80- to-100-story pencil-thin towers crowd the waterfront of Marina City.

The tallest of the group, the Princess Tower, was completed in 2012 and currently holds the title of the world’s tallest all-residential building at 1,358 feet (414 meters) – a height that will be surpassed by 432 Park Avenue in New York, which will top out at 1,396 feet.

Both the Princess Tower and the next tallest of the group, the Elite Residence at 1,246 feet tall, were designed by the architect/ engineer Adnan Saffarini. The strategy for profit in this cluster of seaside stilts is to pack many apartments per floor. Described as 107 stories, the Princess Tower contains 763 apartments, and the Elite Residence comprises 697 units in its 91 stories. By contrast, 432 Park Avenue has only around 100 apartments.

111 West 57th Street. Image: DBOX. Courtesy of SHoP Architects, PC.

Developer: JDS Development/

Property Markets Group

Architect: SHoP Architects, PC

Structural Engineers: WSP Group

MEP Engineers: JB&B

Façade Engineers: Buro Happold

Height: ± 1300 ft | 396 m | 76 floors

111 West 57th Street

With a profile and decorative pattern that looks like a feather quill stuck into an inkwell, the proposed tower at 111 W 57th St. will capture a world record in a category that has previously had little attention: world's most slender building. With a ratio of base-to-height of 1:23, it will far surpass the 1:20 of Hong Kong's Highcliff, whose ten-year tenure with the title illustrates how little competition there has been to erect slender spires. The contrast between the sleek blue-glass curtain wall of the Asian towers' extruded oval and the stepped-back silhouette of 111 W 57th St. with its textured terra-cotta wall that disguises the concrete shear wall structure shows the inventiveness of both the architect SHoP and the engineer, the WSP Group.

In the words of the project's architect, SHoP, "the tower massing accentuates its required setbacks along 57th street with a feathering of multiple, thin steps along the south side façade. Each step corresponds with a layer of intricate terra cotta pilasters cladding the east and west façades. The façade is designed to read at multiple scales and vantage points; the shaping of the terra cotta creates a sweeping play of shadow and light from the city scale, as the texture of the terra cotta panels and inlaid bronze filigree provides richness up close. A minimalist, glass curtain wall along the North façade will take full advantage of the tower's sweeping views of Central Park."