Tenement Crowding

This introductory section of the exhibition presents a timeline of the private and public housing featured in the "case studies" in the main gallery space. The overview highlights the themes expanded in the individual cases, scale models of buildings and neighborhood districts, and historical documents.

* * *

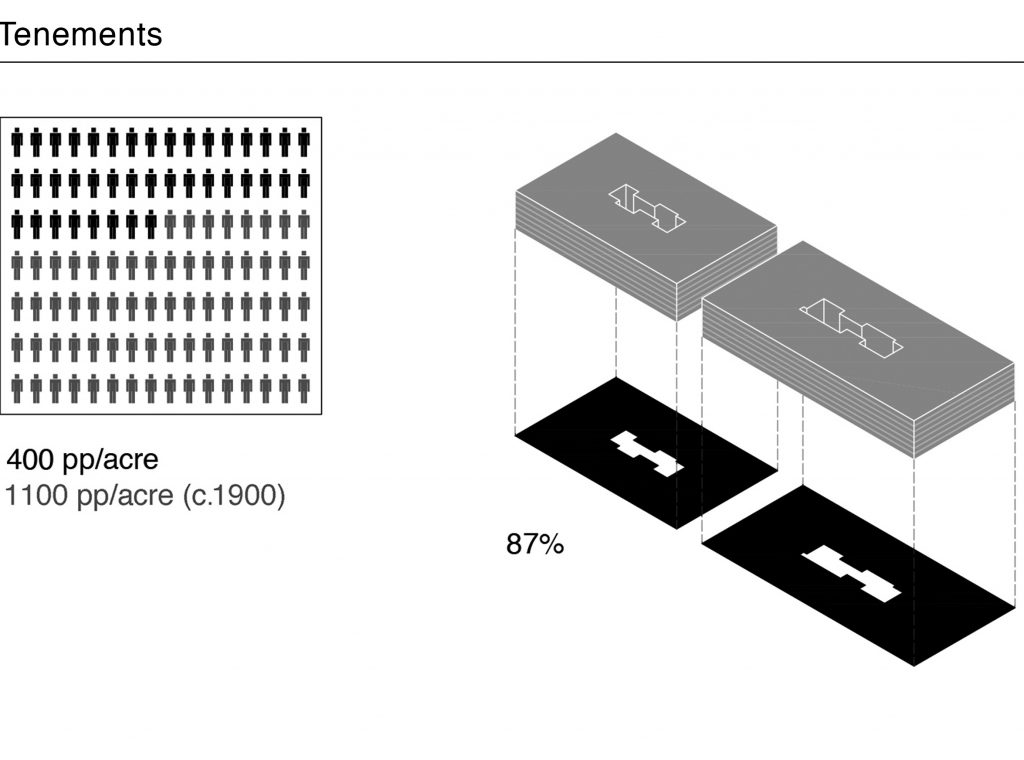

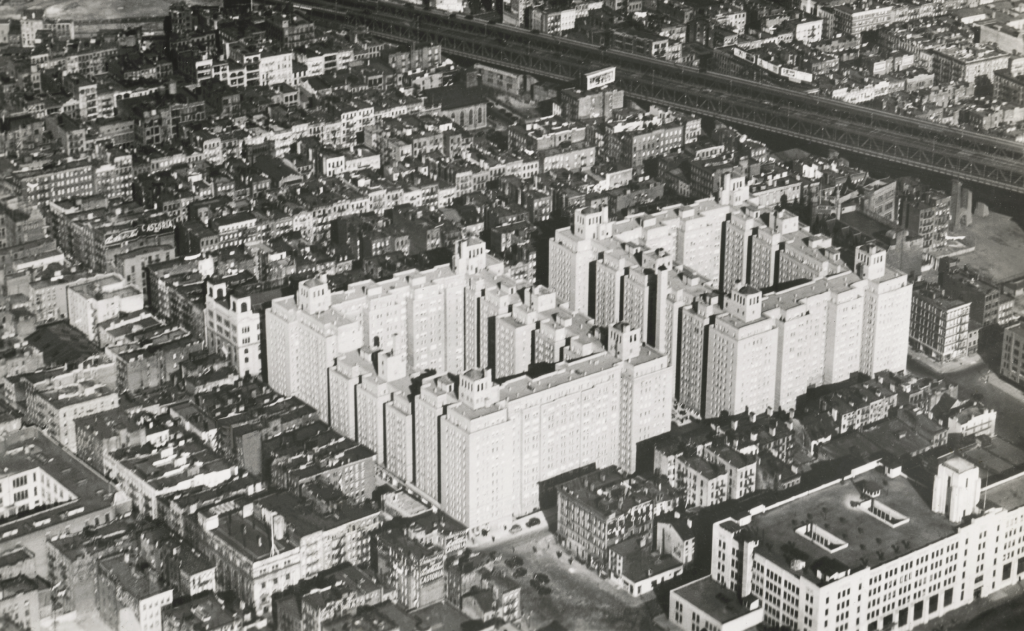

By 1900, the density of population of the tenement districts of Manhattan’s Lower East Side was the most extreme of any city in the world. In the infamous Tenth Ward, the census counted up to 1,100 people per acre, crowded into buildings of 4- or 5-stories that covered as much as 87 percent of the lot and block. These suffocating and unsanitary conditions were so demonized in New York reform circles that the term “density” carried a negative connotation for decades.

Tenements were profitable for investors, who fought against regulation. Early efforts at reform (1867, 1879) were weak and did not affect existing buildings. Model tenement competitions and a few small demonstration projects failed to find a way to remedy a cruel market. After decades of activism, the 1901 Tenement House Law (New Law) finally mandated larger lot size, courtyards, modern amenities (heat, hot water, larger rooms, and private bathrooms), and a rule limiting overcrowding. The New Law also required that old tenements be updated with indoor plumbing and water service. Nevertheless, as the population grew to 3.4 million residents in 1900 – more than a third of whom were foreign-born – the pressures of overcrowding remained a public health menace.

Many reformers hoped that the New Law and, after 1904, the expanding subway system would provide a one-two punch that would reduce the density levels of the city’s tenement districts. Yet built density remained high: New Law tenements could still be built at 70 percent coverage on mid-blocks and 90 percent at corners. The occupancy standards per room were also so weak that landlords still packed families and boarders into single rooms. The extreme density of New York’s tenements would, in time, inspire equally extreme solutions to reduce land coverage and people /acre.

Density and Decentralization

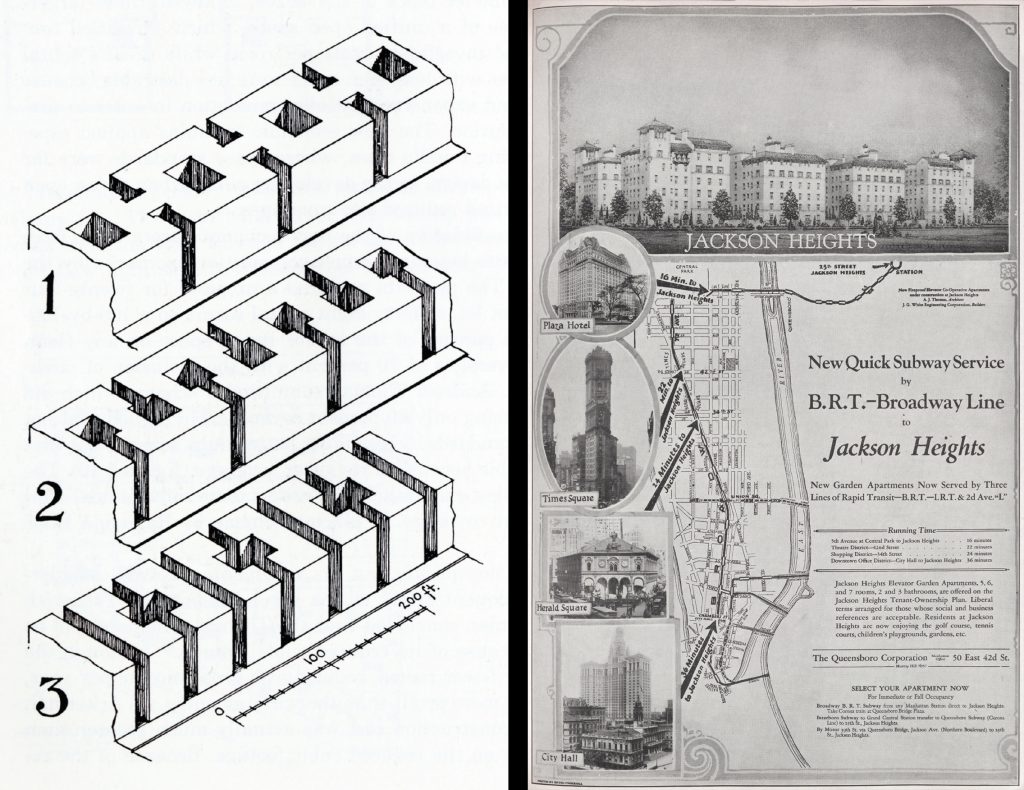

Subway construction in the early 20th century benefitted the rising white middle class as they moved from congested tenement districts to new private houses or apartment buildings in upper Manhattan, the Bronx, Queens, and Brooklyn. The outer-borough garden apartment became New York’s contribution to an international revolution in standards for urban multi-family housing. In Europe, the government-sponsored many of the most famous perimeter-block and garden-apartment projects, but in New York, the private sector took the lead.

Densely developed garden-apartment complexes built by the private sector powerfully influenced New York's interwar housing market. Architect and reformer Andrew Thomas designed variations in Jackson Heights with large apartments and landscaped courtyards. Land coverage was lower than tenements (initially about 70 percent open space) and the people per acre in one early project was just 188. Density later rose to over 300 pp/acre with more closely packed and taller buildings, but the leafy courtyards and large units imbued a serenity of affluent family life. Versions of the courtyard type became a staple of neighborhoods along subway lines, yet few offered an equivalent quality of site planning to Jackson Heights. Nor were most high-quality apartments affordable to any but the middle classes or above.

Reformers dreamed that the working class might benefit from the burst of creative and healthful design made possible by decentralization. The result, in part, was Governor Al Smith’s Housing Act of 1926 that helped labor unions and other parties build garden apartment complexes for working-class people. The Amalgamated Houses (60 percent land coverage) on the Lower East Side pioneered a slum clearance project with Art Deco details and a cozy courtyard. In the Bronx, the Amalgamated Cooperative Apartments offered families a great leap forward from tenements to garden apartments. Yet the Great Depression, limited funds, and lack of interest or development talent in the union sector limited the impact of the 1926 Act.

Garden apartments remained out of reach for most New Yorkers, particularly those in the worst tenements, but the model of spacious urban living they offered would become a goal for both housing advocates. Many architects and politicians would overlook that, while the garden apartment land coverage and people per acre were low, the open spaces were defined by clear boundaries and enhanced by lush landscaping, making the “garden” as much a part of the design as the housing units.

High-Rise, High Density

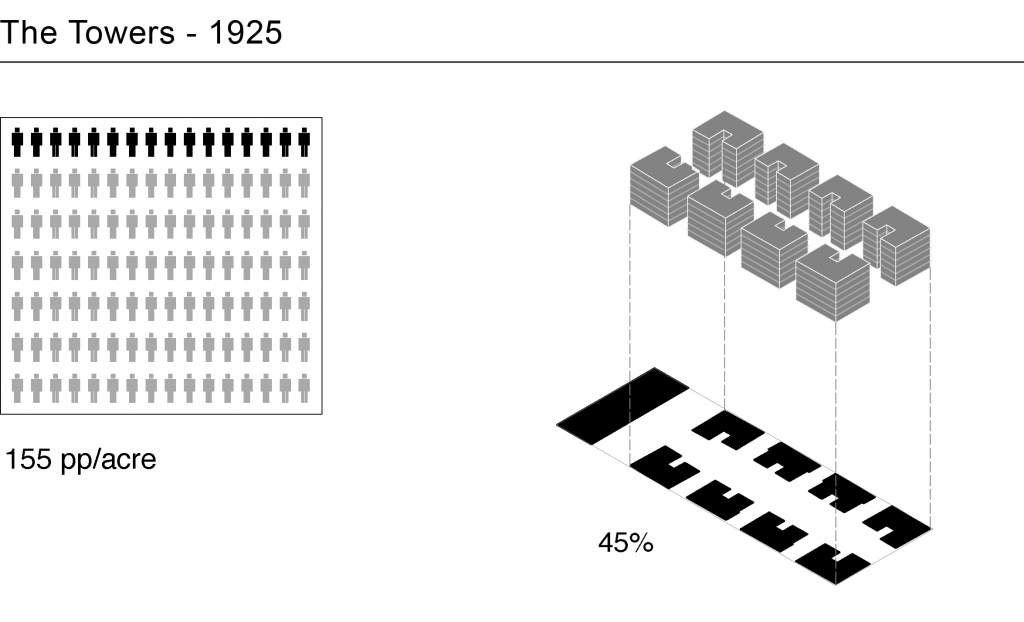

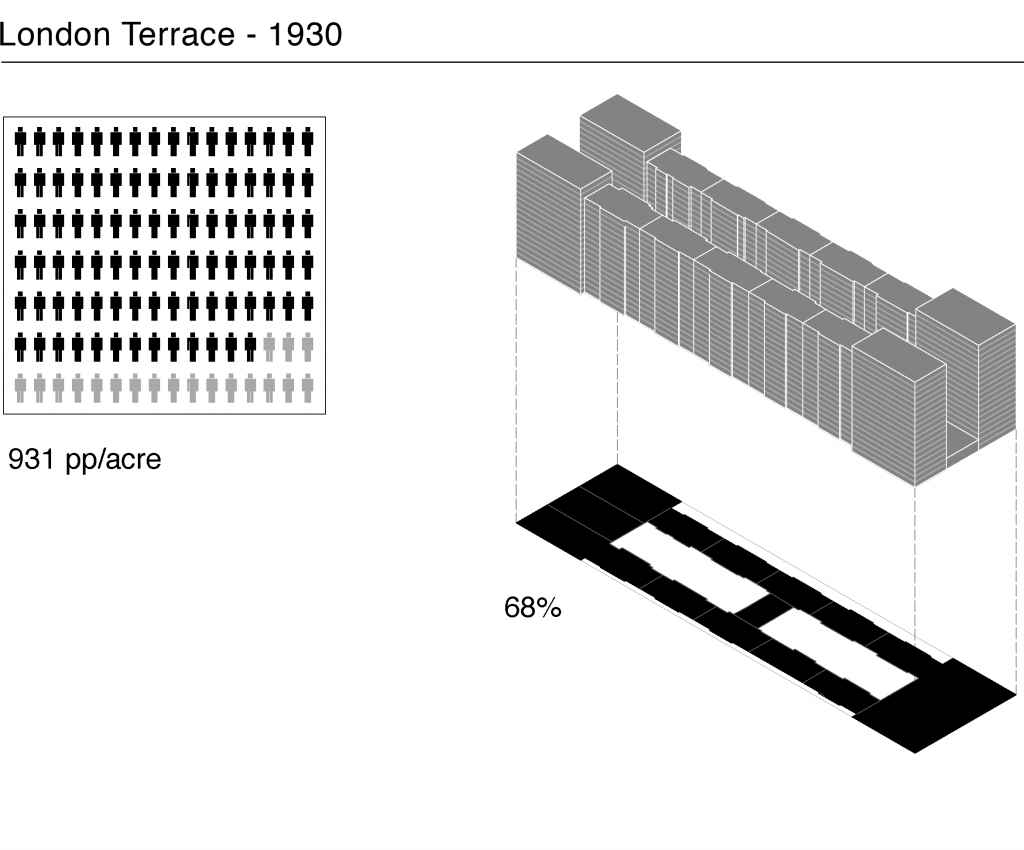

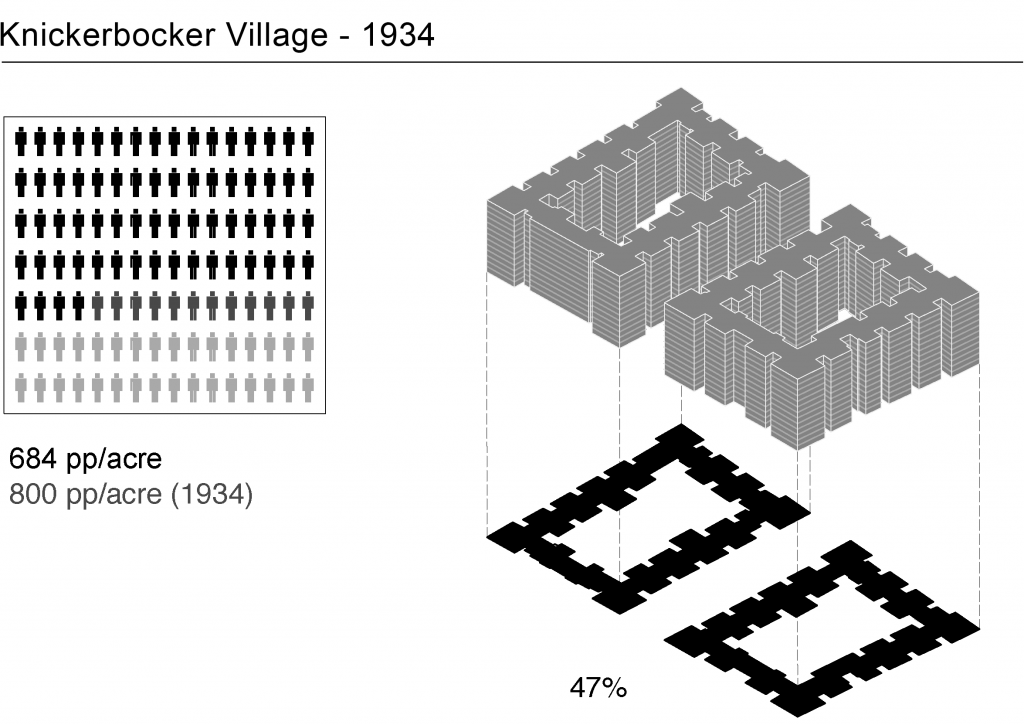

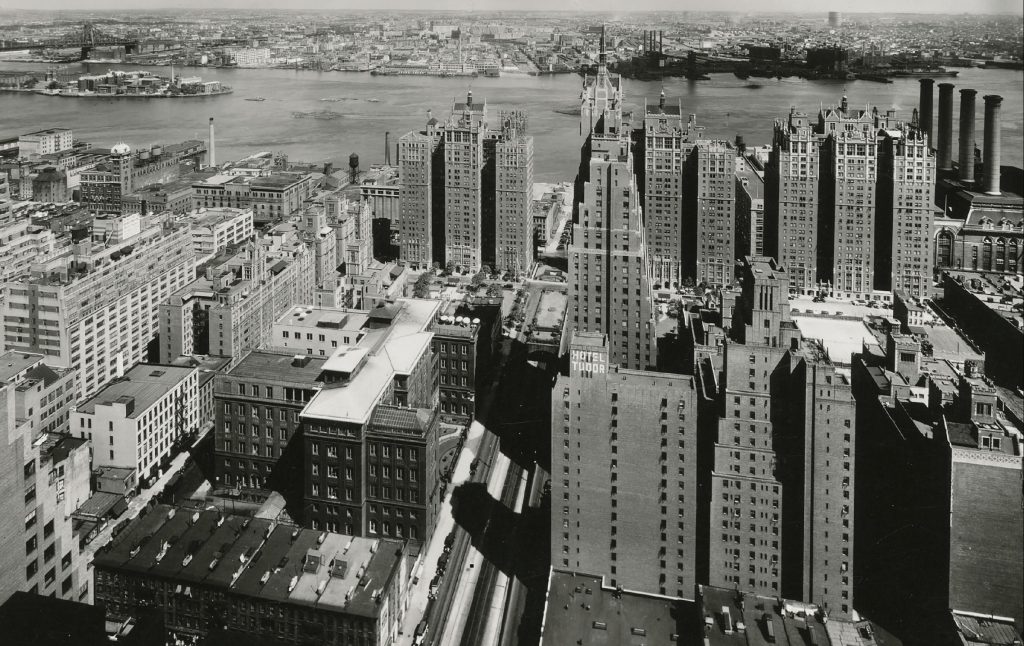

Three examples of very dense high-rise housing developments suggest how the private market might have rebuilt parts of Manhattan for the middle class if the real estate boom of the late 1920s had not ended in the Great Depression. Two were created by the visionary developer Fred French: Tudor City (1927), a 14.5-acre enclave of a dozen towers on E. 42nd Street, and Knickerbocker Village (1934) on the Lower East side, which replaced some of the district’s oldest tenements with modern, but extremely dense, multifamily housing. The other, London Terrace (1930), packed 1,665 units into an avenue-long apartment block in Chelsea. The density of these middle-class developments averaged 463, 800, and 931 persons per acre, respectively.

In the 1920s, the growing obsolescence, squalid conditions, and rising vacancies in old-law tenements near booming business district provoked developers to dream of lucrative, high-density private construction. Businessman Fred French believed slum clearance was the key to making central city life appealing to the middle-class. Successful redevelopment – what he called “scientific rebuilding” – would require wholesale demolition to change the entire atmosphere of a neighborhood so it could compete with suburban life. Underwritten by an investment plan that sold small-denomination stocks that promised solid returns to investors, French quietly assembled hundreds of tenement properties in Midtown’s east side for his Tudor City project.

Clearing for the large hilly site began construction in 1926, and French quickly constructed twelve towers ranging from 10 to 32 stories. The high land coverage and population density were mitigated by the ample open space in adjacent private parks and the quality of the heavily ornamented neo-Tudor buildings. French marketed Tudor City as an amenity-rich alternative for white-collar workers who wanted to “walk to work” rather than endure hours of rail or subway commuting. Designed for the “average salary earner” and his family, the small but luxuriously finished units were complemented by common facilities and overseen by careful community controls.

Similarly, real estate developer Henry Mandel used high-rise density and collective amenities as a strategy for London Terrace, which stretched between Tenth and Eleventh avenues on W. 23rd Street. To create his behemoth block, Mandel demolished 80 historic row houses and multiplied the stories to 22, with 67 percent land coverage. With this strategy, Mandel housed a comparable density of turn-of-the-century tenements in modern apartments at an average of nearly 931 people per acre. London Terrace became the densest multifamily housing in the city, and garnered rents of $52-$130 per room.

Density Reduction

Three decades after the 1901 Tenement House Law, substandard buildings still covered large areas of Manhattan, as well as portions of Brooklyn and the Bronx. As the Great Depression deepened, housing reformers made their case ever more persuasively for both slum clearance and for government assistance to construct housing for low-income families.

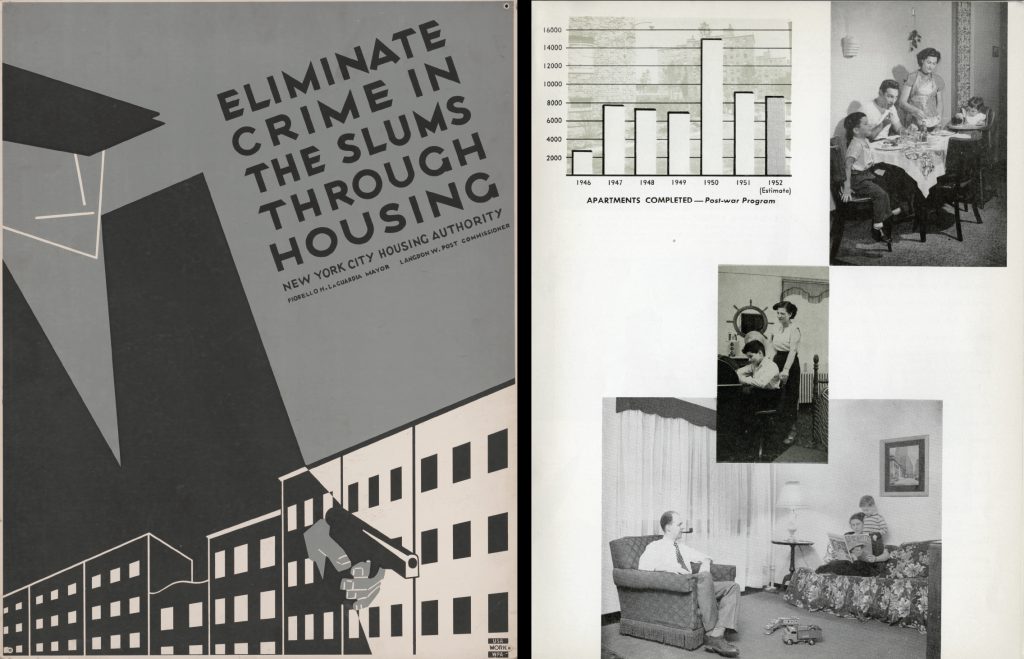

Established in 1934 by New York State, the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) became a powerful force for slum clearance under the leadership of Langdon Post, who served as both NYCHA Chairman and Tenement House Commissioner. Between 1934 and 1936, the authority demolished 1,100 old law tenements. Owners abandoned another 40,000 apartments rather than upgrade them to the much higher sanitary and safety standards mandated in the Multiple Dwelling Act of 1929, which also included more rigorous occupancy standards.

Demolition of tenements and code enforcement intentionally reduced land coverage and population density. The crackdown aimed, above all, to create political pressure for public housing. In the words of Langdon Post, “The only way to get action is to create the need.” NYCHA simultaneously launched a housing program to deliver the replacement housing. Mayor LaGuardia predicted that affordable housing “would become exclusively a function of government because of its important relation to government control of public health.”

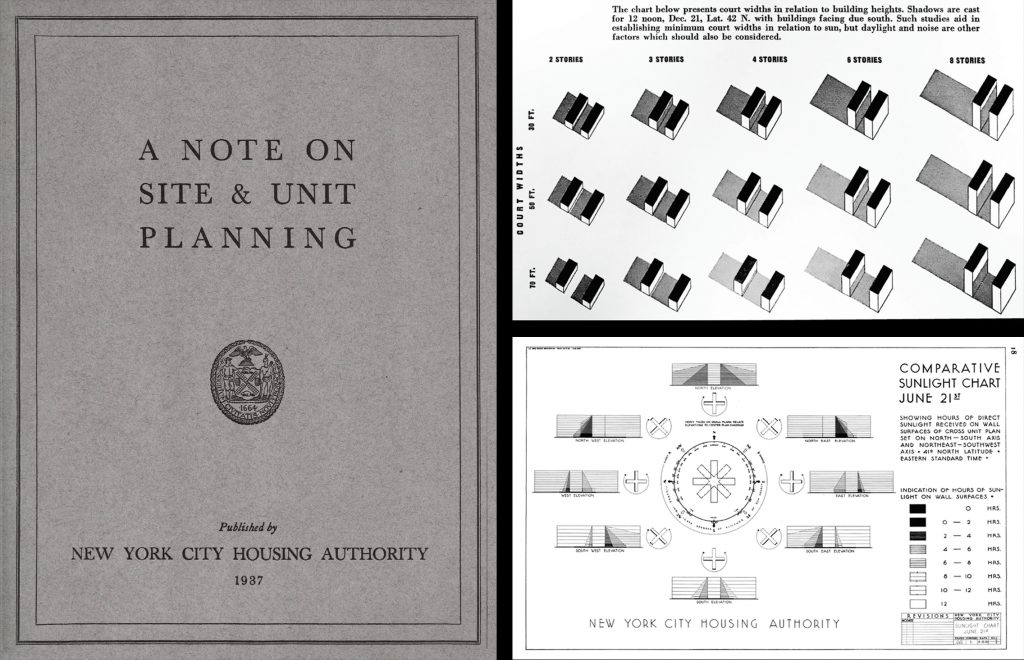

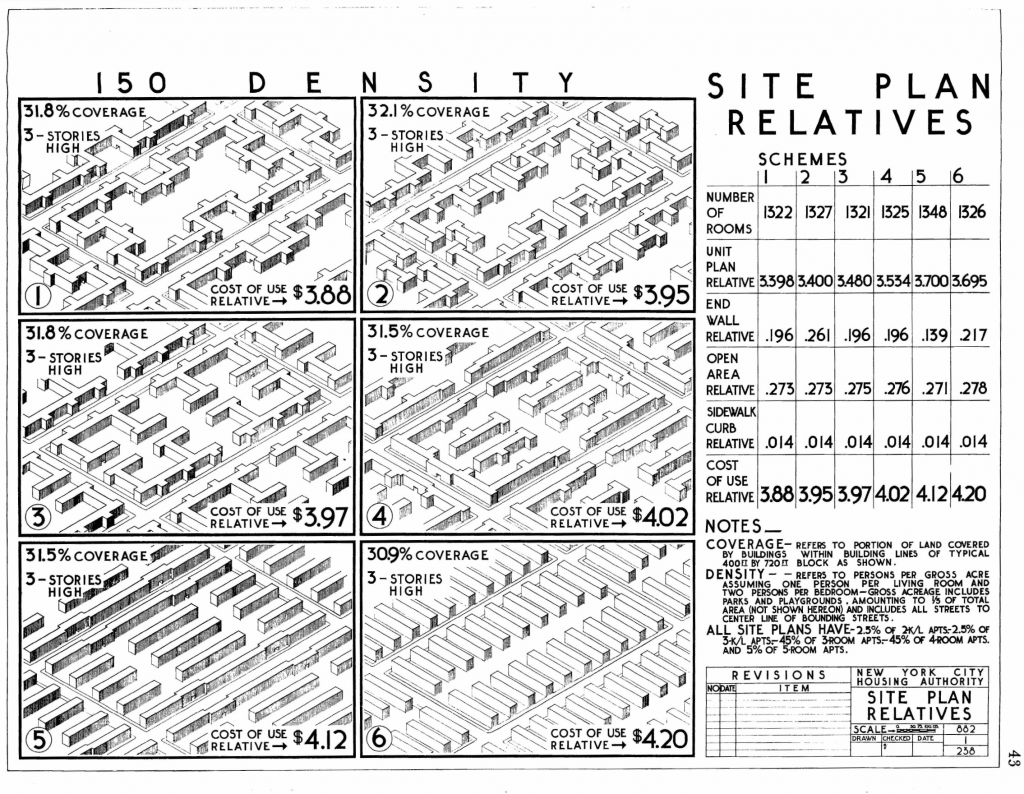

As early as 1936, NYCHA developed a catalog of site planning solutions, illustrated by the diagrams here, which satisfied its self-imposed standards of low population density and low lot coverage, building height, and construction costs. This standardization effort was led by Frederick L. Ackerman, chief architect of NYCHA’s Technical Division, who sought to secure the maximum amount of open space and sunlight at every site. Ackerman’s standards established the principles for several decades of public housing. Although the early slab buildings would later become Y-shaped plans, and eventually “towers in the park,” the ranges of land coverage and people per acre (100-250) set in the 1930s remained in place through the 1960s.

NYCHA's Production

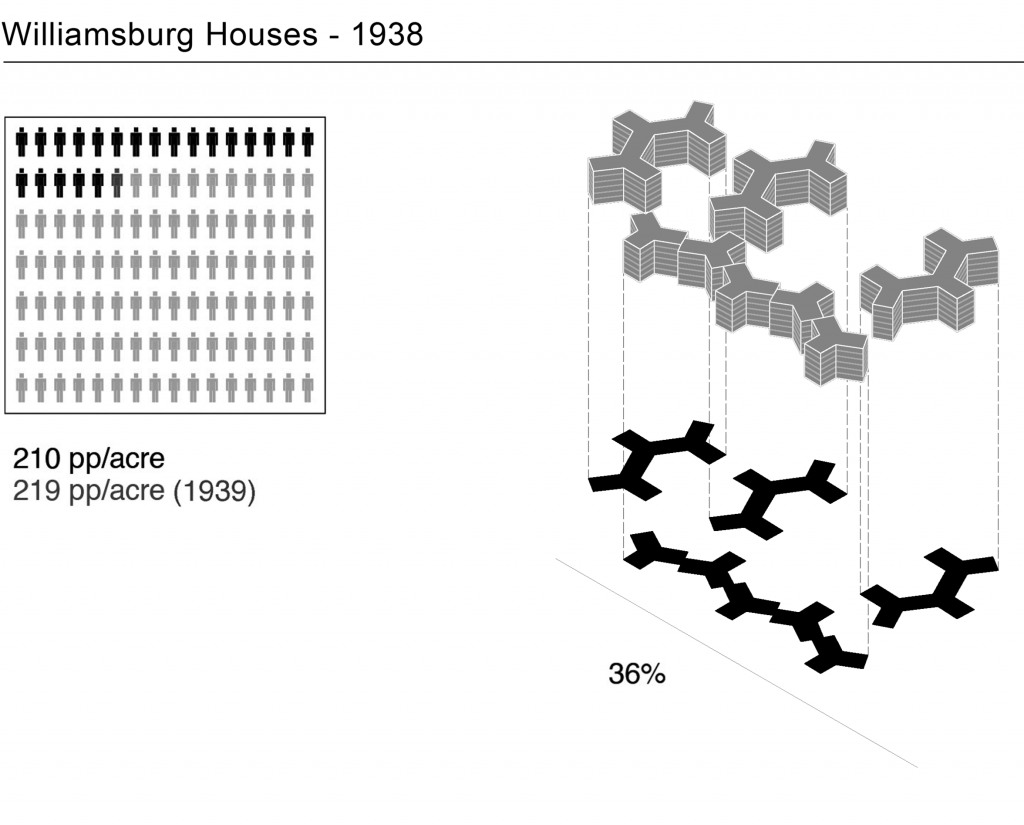

NYCHA architects worked to develop housing models that would dramatically reduce density and maximize solar orientation. After the experiment of First Houses, a problem-plagued attempt to both demolish and rehabilitate tenements on the Lower East Side, NYCHA turned to new construction. A pioneering project to demonstrate their goals and guidelines was Williamsburg Houses, designed by the noted Swiss-American modernist William Lescaze, together with Richmond Shreve and the NYCHA team, and built between 1936 and 1938. Its twenty buildings had T- and H-shaped plans that were oriented at a 15-degree angle from the street grid to gain better exposure to sunlight. At four stories, the buildings were walk-ups, the lot coverage was about 32 percent, and the density was 241 people per acre. The site, which replaced twelve city blocks of mostly substandard buildings, included a school, community center and neighborhood retail. The project, however, was costly: $13 million.

While NYCHA seemed to endorse a garden-apartment approach at Harlem River Houses (1937), in truth Ackerman and other architects remained devoted to more radical schemes such as Queensbridge Houses (1940). The large site, nearly 50 acres of former industrial land just north of the Queensboro Bridge, was purchased for only $1 per sq. ft. The size and repetitive design allowed for standardization, economies of scale, and efficient use of costly foundations in 6-story elevator buildings. NYCHA’s architects were able to both lower density to 209 pp/acre and realize lot coverage of just 18.1 percent, creating acres of open space for courtyards and play areas. Cost cutting required by federal funding produced smaller apartment units and limited commercial or community facilities that pinched the quality of life of many families despite the grand open spaces.

This pattern of density reduction persisted even when land costs became higher. The first Manhattan slum clearance project on the Lower East Side, the 6-story Vladeck Houses (30.7 percent land coverage and 389 pp/acre), was more densely developed than Queensbridge and the property was more expensive at $3.76 a square foot, yet it was much lower density than the tenements it replaced and half that of the developer Fred French at Knickerbocker Village, just down the street.

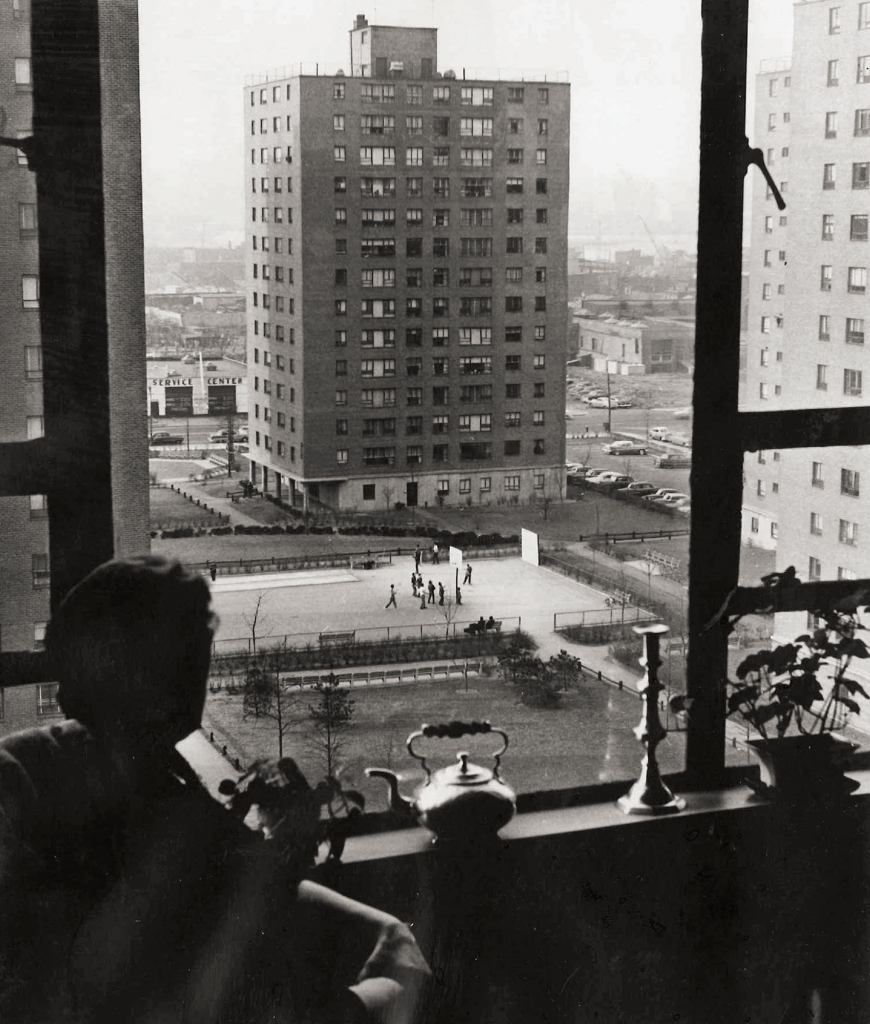

The low density of new NYCHA projects was embraced by the carefully selected tenant families. The popularity of the early public housing system gratified administrators who boasted of the large number of residents moving from old law tenements to light-filled apartments. They also mistook the excitement for widespread endorsement of low density, with dramatic repercussions for the future of the city.

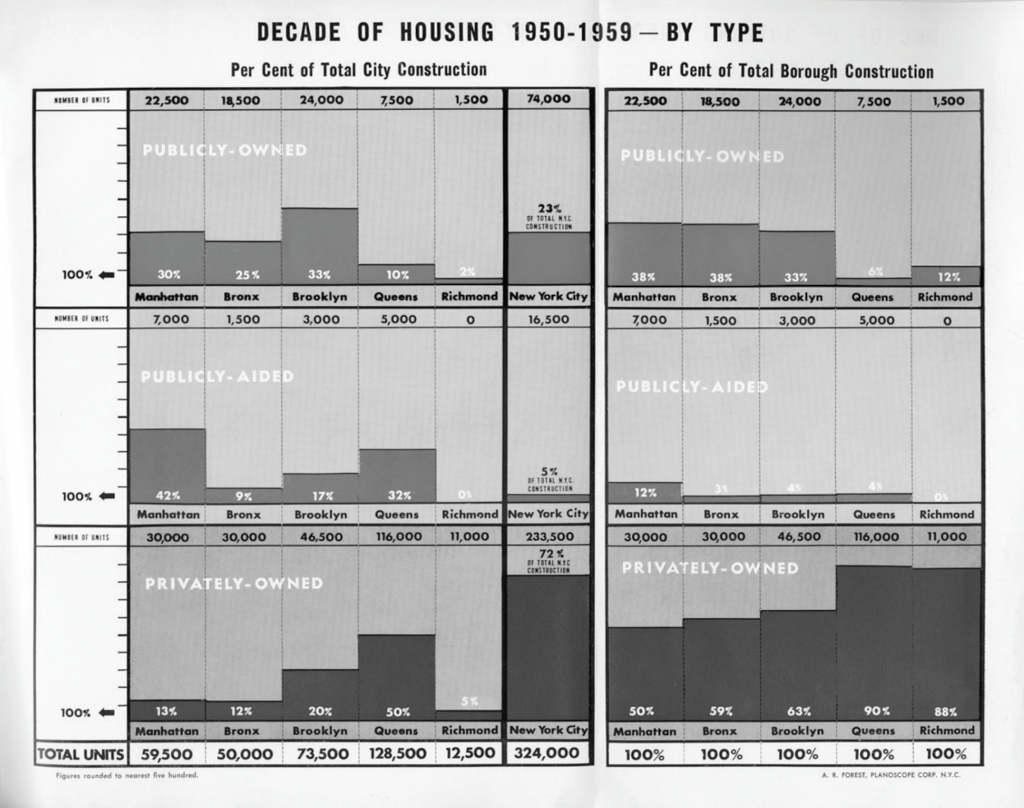

Large Scale, Open Space

In the postwar years, the rise of the middle-class suburb altered public expectations of density in the New York region and across America. Garden apartments and NYCHA projects were low lot coverage and uncrowded compared to tenements, but they were much more dense than suburban single-family homes. Thanks to industrialized production methods, highway access, and Federal Housing Administration (FHA) mortgages, developments such as Levittown helped families jump directly from crowded apartments to private homes with green lawns and backyards on generous 1/10th of acre lots.

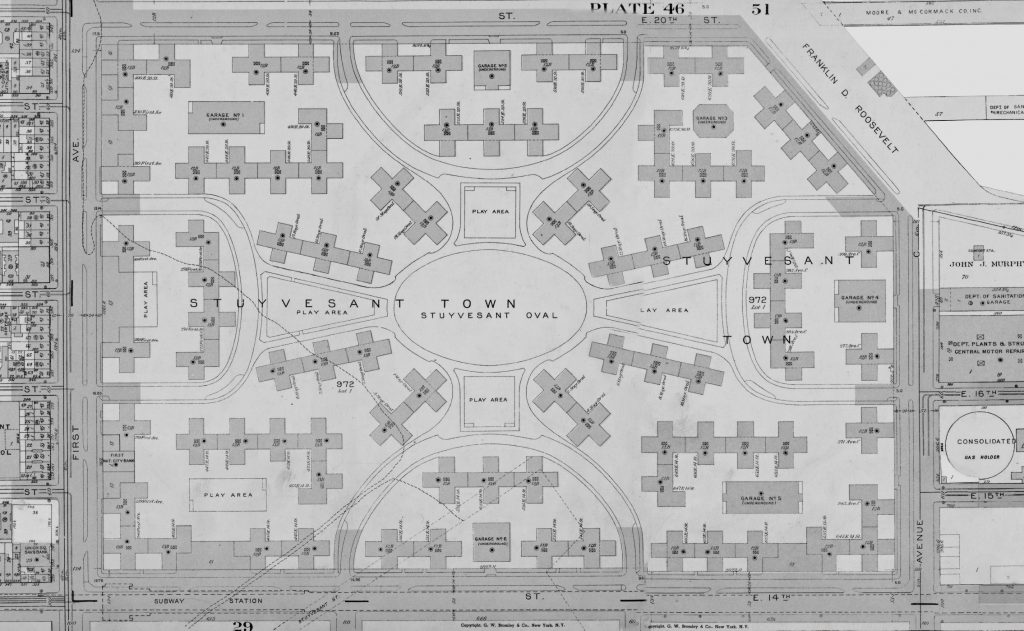

Within the boundaries of New York City there were successful attempts to find a middle ground between high-rise living and single-family concern that New York might become a city divided between rich and poor. Thanks to changes in state law that allowed insurance companies to enter the area of residential real estate, as well as federal programs available through the FHA and the slum-clearance efforts of Robert Moses, companies such as Metropolitan Life Insurance Company developed several large-scale, master-planned, high-rise communities for the middle class in the 1940s and 1950s.

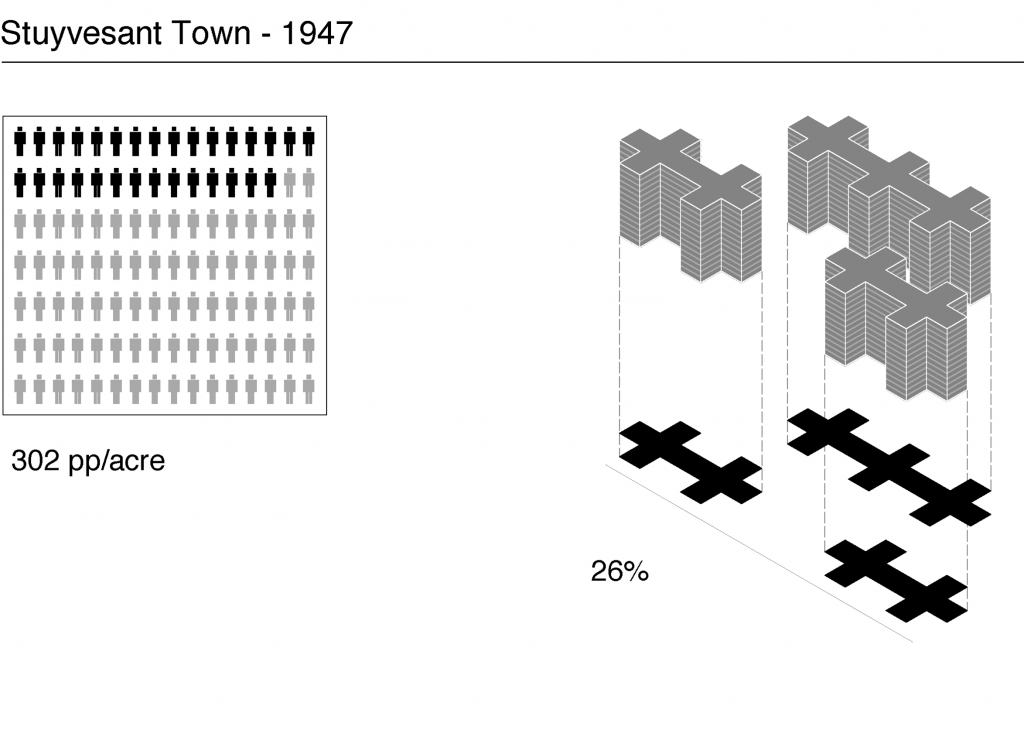

The largest and most significant development in Manhattan was Stuyvesant Town/ Peter Cooper Village (1942-48). The massive project stretched from 14th to 23rd streets and from First Avenue to Avenue C. It required a slum clearance program paid for largely by the City, which also granted the project tax exemption for 25 years. The emphasis of the master plan, which de-mapped seven city streets was on tree-filled lawns between the identical towers and central community areas of parks and playgrounds. Parking was limited, as access to transit was emphasized. The Stuyvesant Town section covered only 26 percent of the 80-acre site and yet delivered 302 pp/acre thanks to the 8,757 apartments stacked in 15-story buildings. As with NYCHA, sponsors carefully managed occupancy to prevent crowding that would add density.

Middle-Market Design

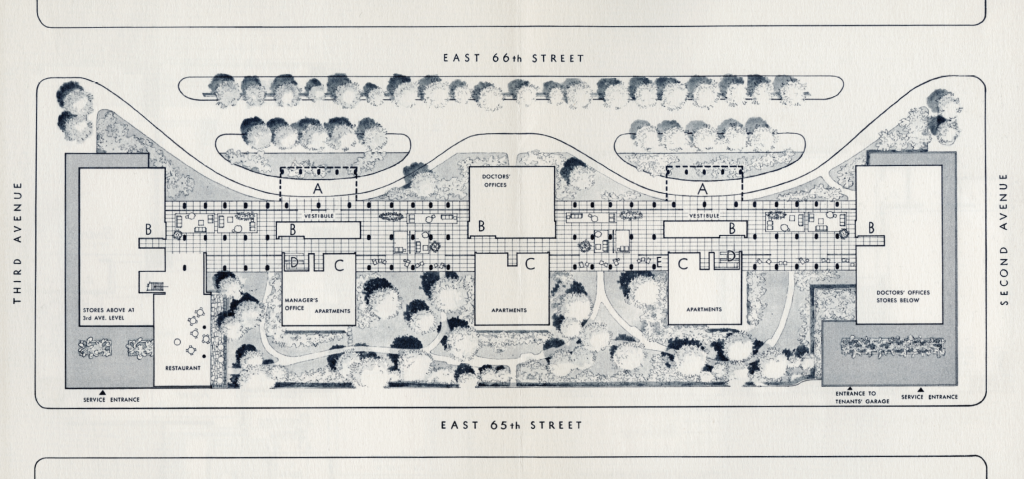

As New York City rebounded during and after World War II and pressure grew for high-quality rental apartments, private companies began to rethink their aversion to residential development in Manhattan. Some began buying up older tenements and commercial buildings that were moderately priced, yet located in areas ideal for residential growth.

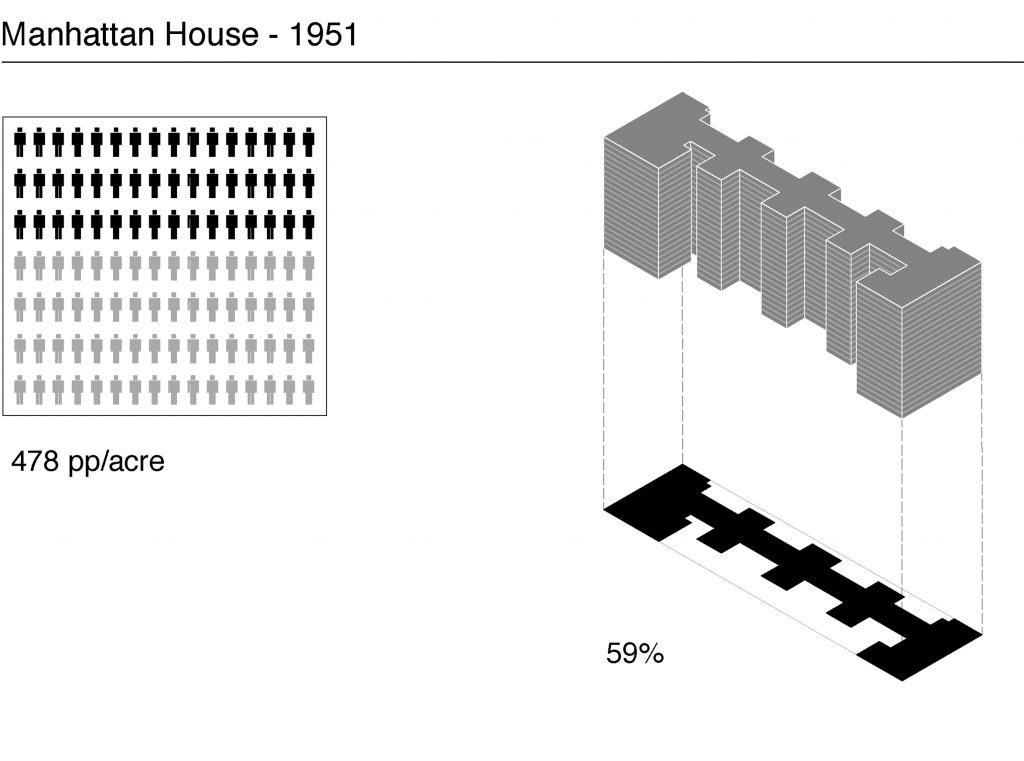

A pioneering project was Manhattan House, which was developed without subsidies by the New York Life Insurance Company from 1947-51. Located between 65th and 66th streets between Second and Third avenues, it occupied a full block in an area that was undergoing significant change as the elevated train tracks that had imprisoned that swath of the city were either recently demolished or scheduled for demolition. An old trolley barn, tenements, and assorted commercial buildings were so affordably priced that New York Life bought extra property in the surrounding blocks.

The clean, crisp modernist design by architect Gordon Bunshaft, principal at Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM), which was associated with the firm Mayer & Whittlesey on the project, was an immediate success and attracted famous tenants such as Benny Goodman, Grace Kelly, and furniture designer Florence Knoll, as well as Bunshaft himself. The apartments were spacious, but the overall density was high at 478 pp/acre. Thanks to New York Life’s interest in long-term profits, the building was more “tower in a garden” than “tower in the park” and covered a higher percentage of land (59 percent) than the vast publicly subsidized projects that were its contemporaries.

The postwar volume of privately-developed housing was less than hoped, and minor compared to either new office towers or suburban growth. Had the private sector fully engaged in redeveloping housing in Manhattan, the city would today look quite different. However, the growing fiscal problems and continuing middle-class flight prevented a massive unsubsidized recovery that might have remade the city at a much higher density level.

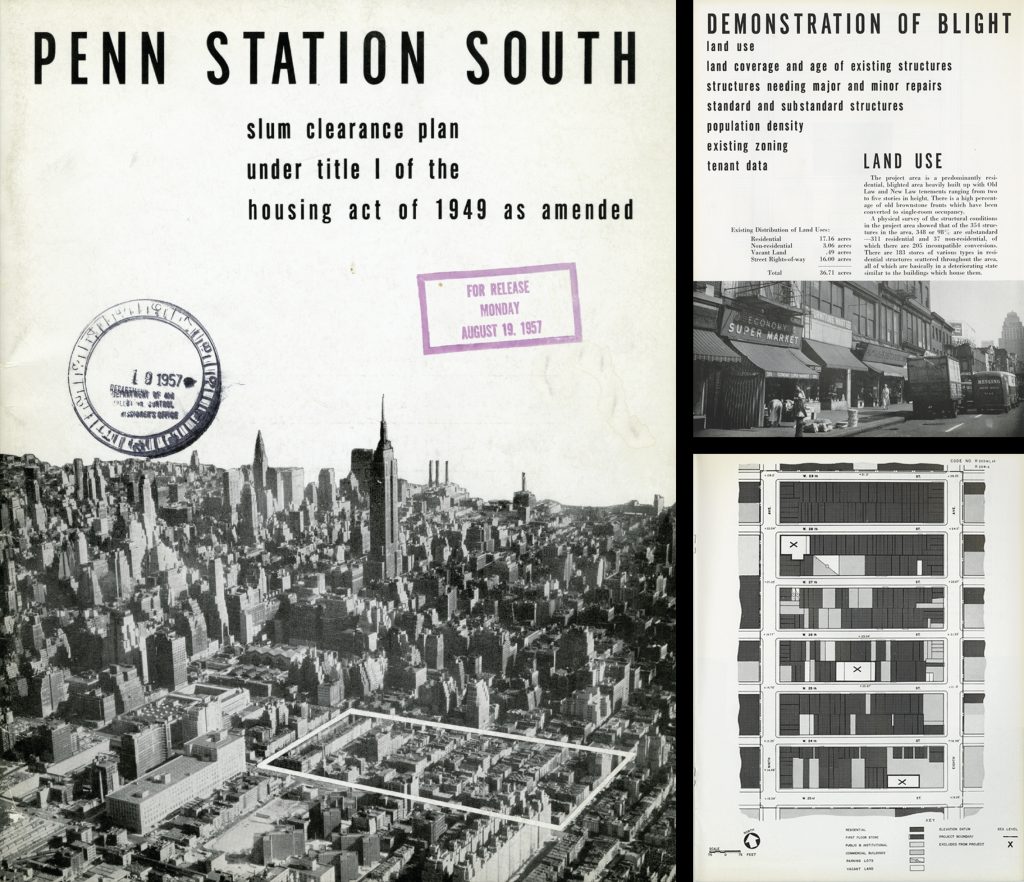

Slum Clearance

Given the low levels of private investment in creating new housing in the postwar years, especially in Manhattan, government officials sought ways to attract developers into renovating tenement neighborhoods. Eminent domain and deep subsidies for construction were tools that federal, state, and local leaders used to engineer new programs and powers, including, most notably, Title I Slum Clearance and Mitchell Lama middle-income housing. The unions needed no encouragement, as they had been eager to rehouse their members in new housing since the 1920s, but Construction Coordinator Robert Moses, Mayor Robert F. Wagner, and Governor Nelson Rockefeller, among others, successfully attracted private builders to urban renewal in the 1950s and 1960s.

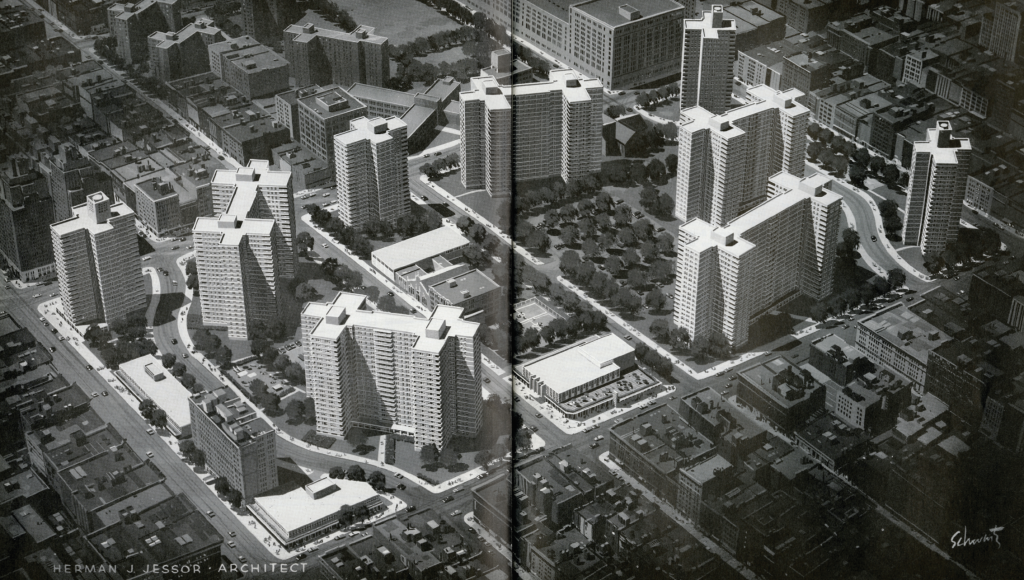

Once designated by the government, private partners in urban renewal were charged with developing both spacious, modern apartments and a new kind of neighborhood. Civic leaders mandated that new high-rise, private projects reduce ground coverage and population density overall.

Participating builders had to accept these standards even though they might have preferred to replace old tenements with more profitable and densely developed apartment houses.

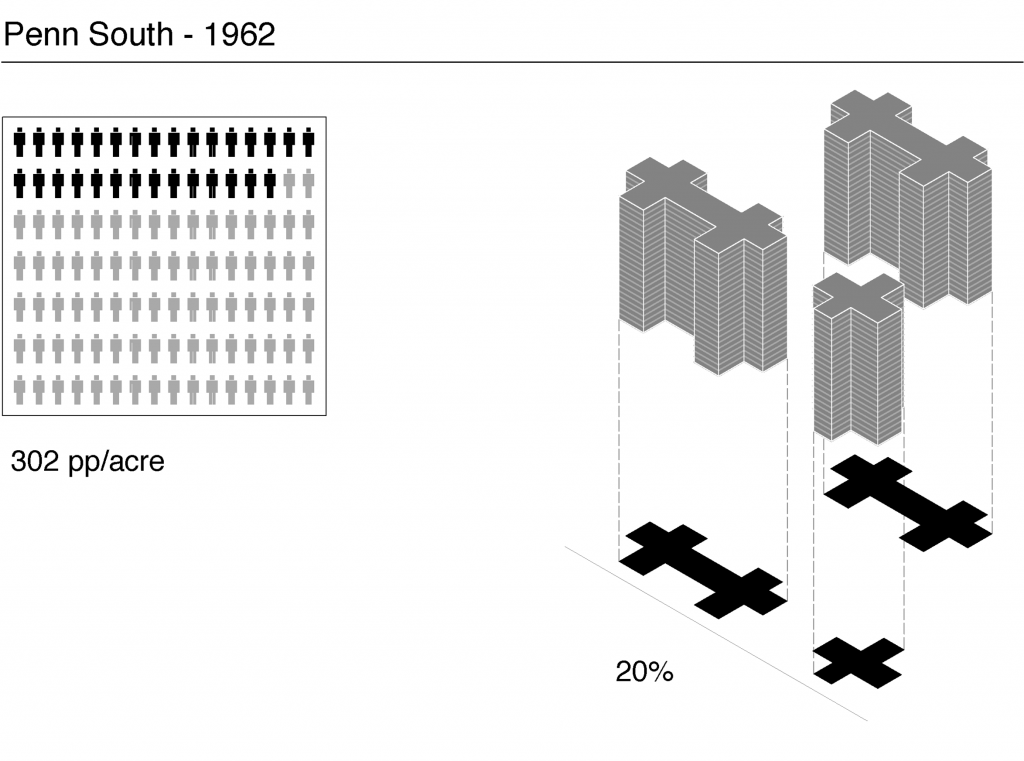

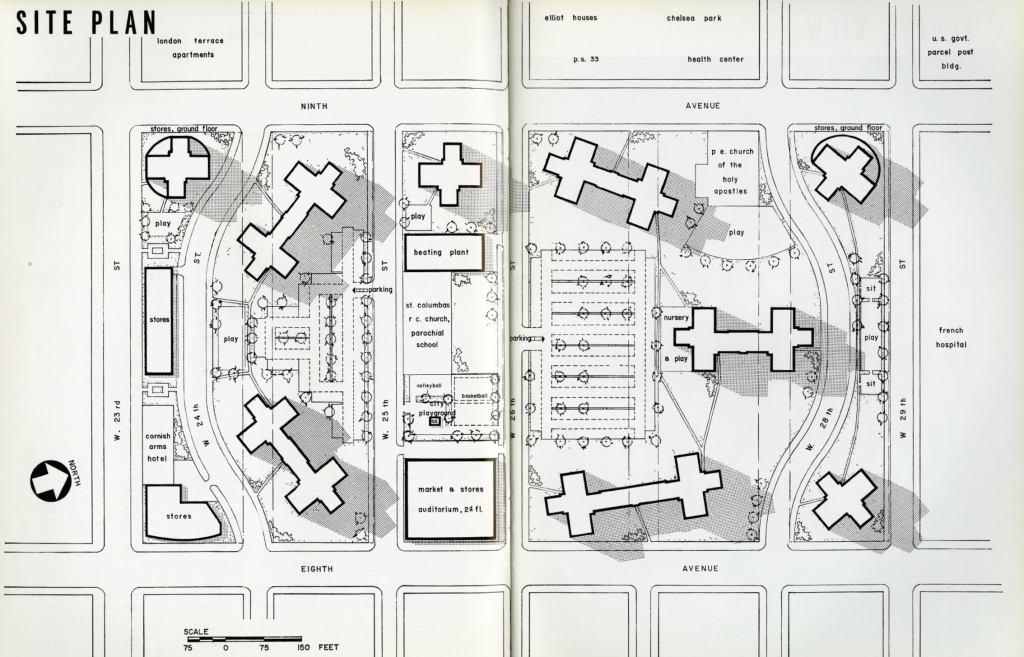

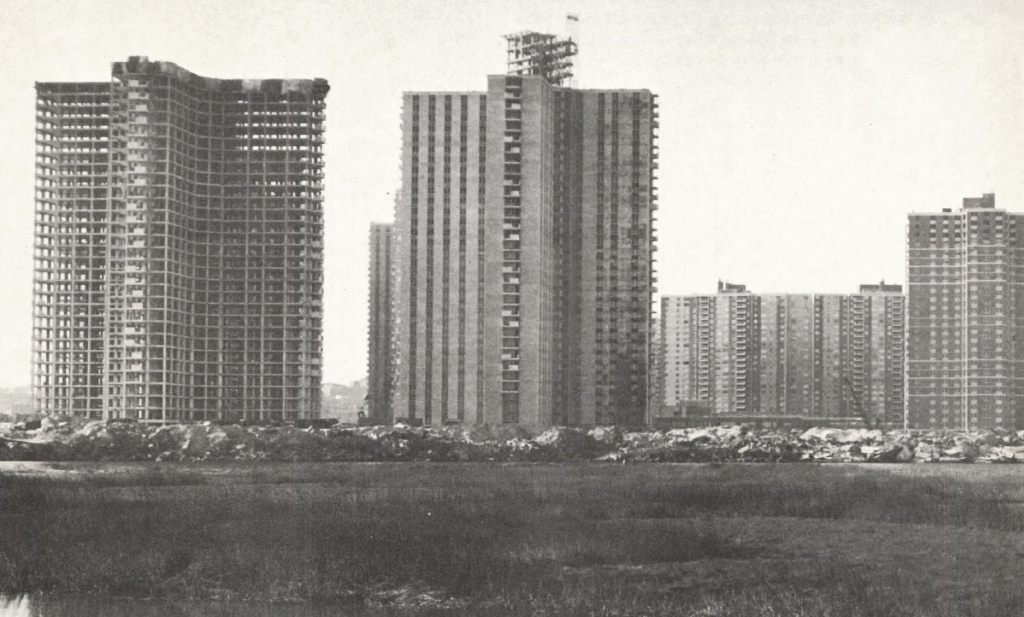

The Penn South Title I project (1962) reflected the density reduction strategy in full flower. Sponsored by the United Housing Foundation, a consortium of labor unions, the vast cooperative project targeted a tenement district in Chelsea with high lot coverage and population density. Penn South’s 20- and 21-story brick towers reduced building coverage from 70-90% to just 17%. The lawns and parking lots, to say nothing of the spacious apartments with balconies, proposed a new way of middle-class life within the city itself. The final population density of just 302 pp/acre, however, was half that of the neighborhood it replaced, leading to significant displacement of tenants with income insufficient for the new project.

The popularity of Penn South, and similar projects under Title I and Mitchell Lama, confirmed for their sponsors that they had succeeded in delivering the highest quality environment ever sold to the lower/middle class in New York’s history. Although some contemporary critics such as Jane Jacobs and Lawrence Halprin complained of the low density and uninspiring landscape, Penn South remains a successful cooperative beloved by its residents today.

Towers in the Park

“Tower in the park” is the shorthand phrase that describes the master-planning approach of most public- and publicly-assisted housing constructed in New York from the late 1930s through the 1970s. The architectural form and planning theory had its origins in European modernism of the 1920s and especially in the ideas of the Swiss/ French architect Le Corbusier. The avant-garde model of European social housing emphasized simple functionalist buildings, unadorned by design. The “park” aspect of the formula emphasized ample landscaped open space between buildings and access to sunlight. The European buildings were multi-stories, but rarely truly “towers.”

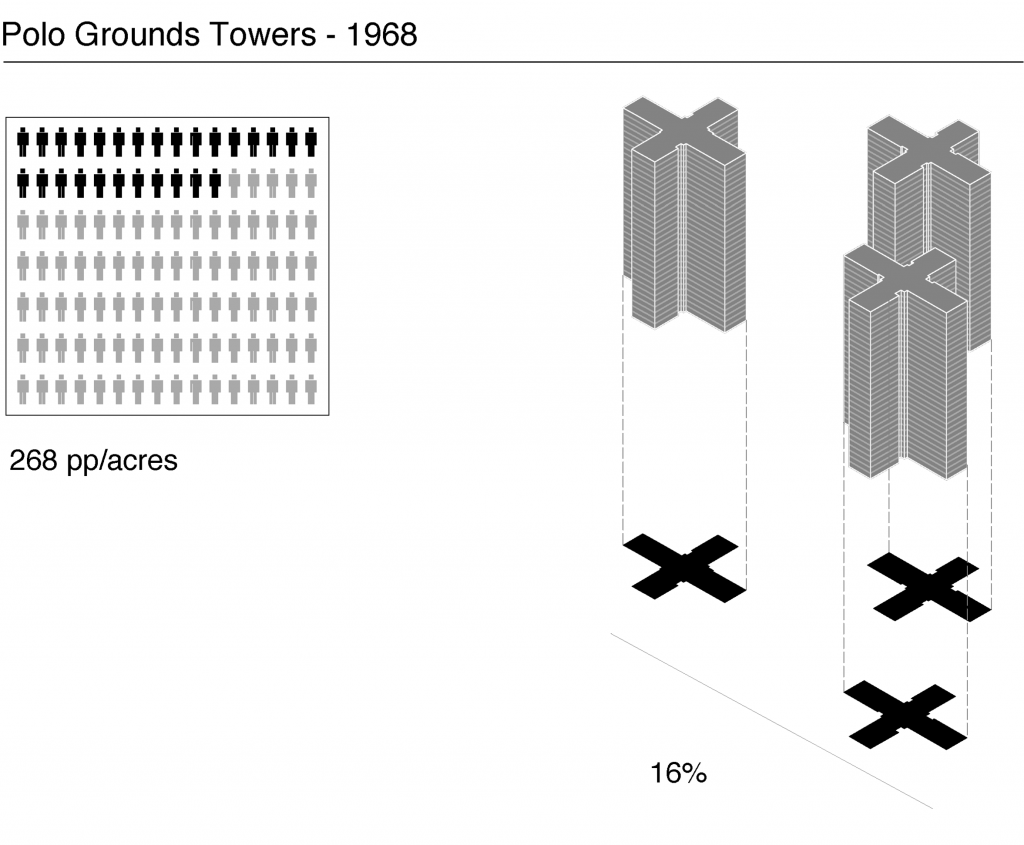

NYCHA architects and the many private firms they worked with integrated modernist planning principles into the dominant strategy of density reduction. For them, the ideology of open space and sunlight was paramount – but also matched by necessity of economy, achieved through standardization. Uniform buildings, replicated on a large scale, cut construction costs and achieved economies of scale. According to NYCHA architects, “two factors largely shaped the buildings of this period: efficient use of elevators and fireproof construction.” Buildings spelled out an alphabet of X, T, and Y site plans, leading to “complete standardization of exterior detail: red brick with standard window types and little or no elaboration such as balconies.”

The height of typical NYCHA buildings grew substantially from the six-story formulas at Queensbridge and Vladeck Houses. Typical 1940s and 1950s NYCHA projects in Manhattan often ranged from 10-16 stories, and by the late 1950s could rise to 20 stories. There was an obvious logic to using taller buildings to multiply the number of people housed: that was, after all, the strategy of private developers Fred French or Henry Mandel at Knickerbocker Village and London Terrace. But NYCHA architects were committed to maximizing open space, so where they made the buildings taller, they traded the "vertical density" in the towers for more open space on the ground. The most extreme example was uptown at the Polo Grounds Houses (1968) where four 30-story towers covered only 12 percent of the vast site.

The tower-in-the-park model became ubiquitous in the postwar years, not just for NYCHA projects, but for all publicly-assisted housing in the metropolitan area and beyond. All seventeen of the Title 1 projects proposed by Robert Moses and the Mayor’s Committee on Slum Clearance in 1956 used it. As Moses summarized bluntly: “to accommodate large numbers of people more comfortably, the answer is vertical construction on less land. Instead of building four or five stories, covering 80 or 85 percent of the land, you go up four or five times as high on 20 percent coverage. This will leave plenty of open space, playgrounds for kids, and better views.”

Minimal Density

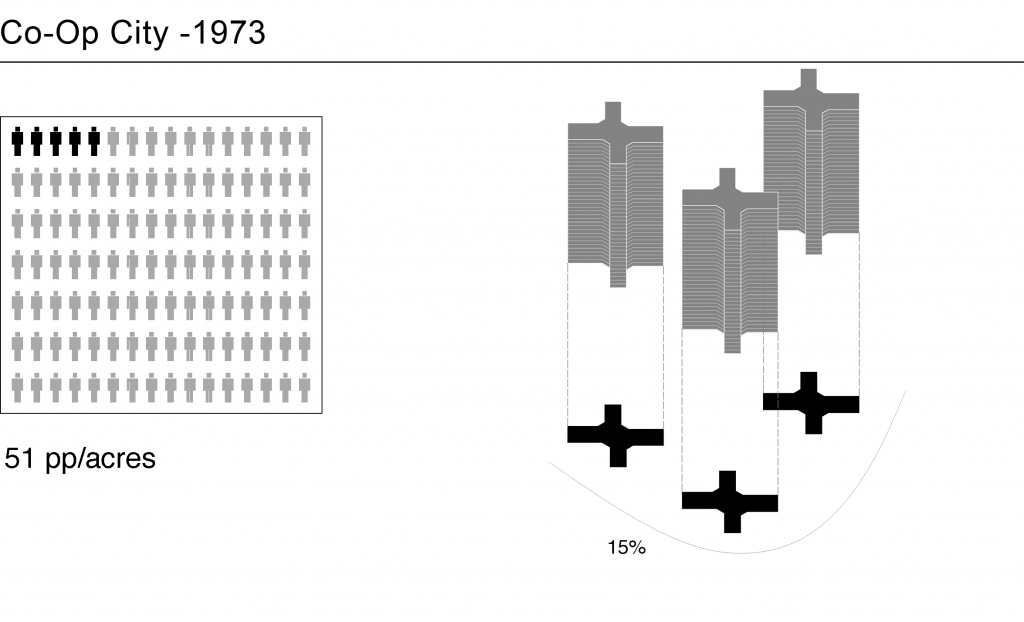

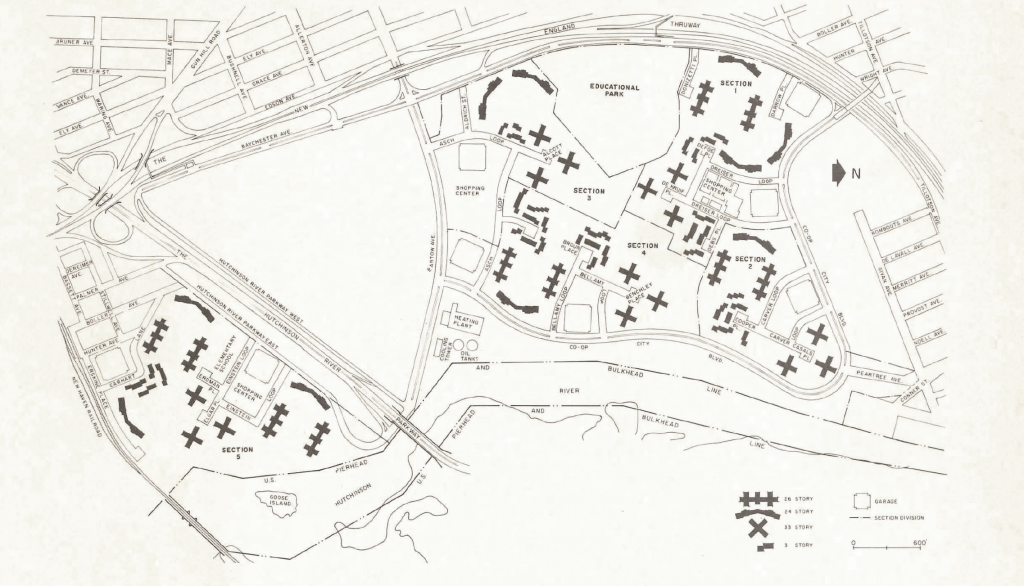

The final chapter in the policy and programs of density reduction took place in new large-scale communities underwritten by New York State through the Mitchell Lama program. State and City housing administrators had come to believe that projects had to be large enough to reset the environment of whole neighborhoods. Having experienced problems with some smaller projects inserted into declining neighborhoods in the Bronx and Brooklyn, officials concluded that big projects with low density were the best way to compete with suburbia.

During the 1960s the United Housing Foundation would sponsor tens of thousands of units, the most of any non-profit sponsor. At vast cooperatives like Rochdale Village and Co-op City, the UHF built communities that looked urban from a distance, but on closer inspection were not terribly distinct from suburban areas. Thanks to large, cheap, and vacant parcels of land, tall buildings, and large single-family apartments, the density levels per person were very low. Co-op City, constructed from 1968-75 with 15,382 units, boasted 33-story towers that covered just 15 percent of the land and delivered just 51 pp/acre.

Some critics, architects and planners, disillusioned by the widely spaced towers floating in undifferentiated greenspace, sought alternatives to formulaic towers in the 1960s and ‘70s. The State’s Urban Development Corporation (1968) was a short-lived but powerful force for reforming the density reduction ideology, including a “low-rise, high-density” program of housing that its proponents believed was better scaled to human needs and community life. But the cancellation of federal housing programs, and the collapse of the UDC that followed in 1975, ended these promising density experiments.