Immigration and Overcrowding

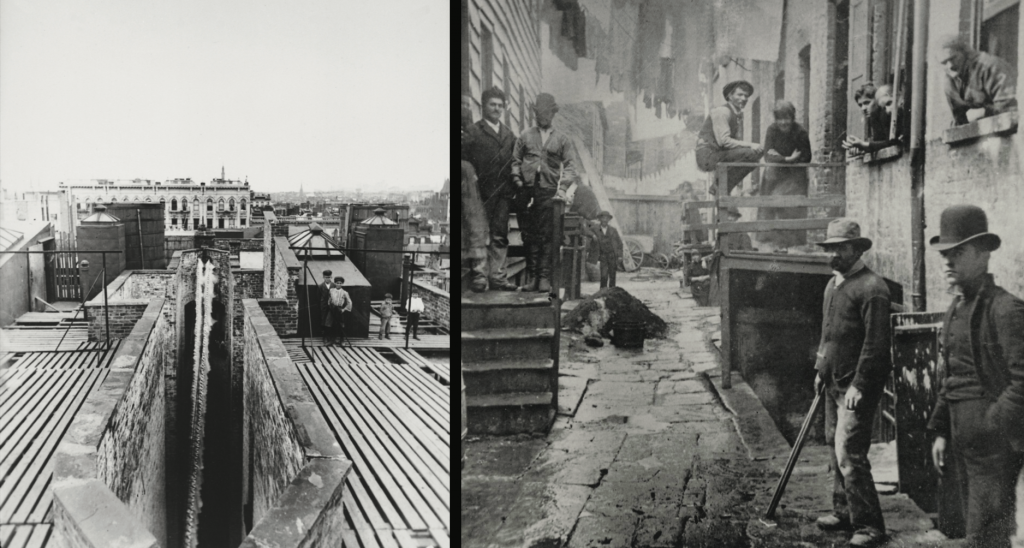

New York’s slumlords began erecting purpose-built tenements before the Civil War, and by 1866, reformers had already noted that “a degree of crowding has been attained which by itself has become a subject of sanitary inquiry and public concern.” The situation worsened in the following decades as landlords and builders met the exploding need for housing in areas like the Lower East Side by packing taller walk-ups onto narrow lots and renting apartments by the room. Light barely penetrated to lower floors and windowless rooms were a byproduct of overbuilt lots. In a typical tenement of the era, a toxic privy blighted what little open space remained. Overcrowded apartments exacerbated problems, such as the spread of disease from shared hall toilets or death from fire.

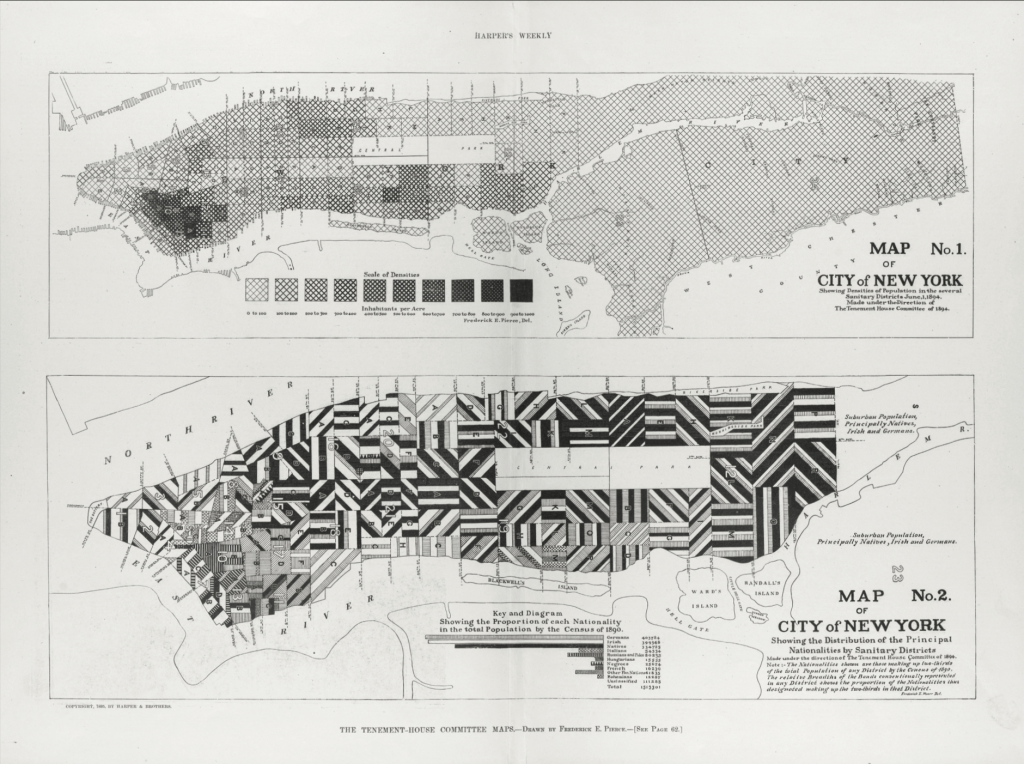

Immigration fueled the need for working-class housing. By 1900, the population of New York City had grown to more than 3.4 million, of which 1,270,080 (37 percent) were foreign born. Nearly two-thirds of New Yorkers (2.3 million) occupied some 82,000 tenements, about half of which (42,000) were in Manhattan. The neighborhoods with the most tenements reached unprecedented levels of crowding. In 1903, in the Tenth Ward on the Lower East Side, the average density was a striking 665 people per acre, and one particularly dense block packed 2,223 residents into just two acres – averaging more than a thousand persons per acre. Historian Andrew Dolkart reports that the block’s 34 buildings primarily housed those newly arrived from Russia: “Of the 310 heads of families, 186 were of Russian parentage; the next largest groups were from Austria-Hungary (52) and Germany (29).” Many of these newly arrived families were large, even though the apartments were small: of the 310 tenement families, 176 had five or more members.

The maps of density and foreign-born nationalities, commissioned in 1894 by the Tenement House Committee, and published in Harper’s Weekly in January 19, 1895, offer details.

High land values, weak building laws, and population pressure encouraged new tenement construction in other emerging neighborhoods such as East Harlem, Williamsburg, and Brownsville. It was hard to shake tenement life for working-class New Yorkers.

To say that in one section of the City the density of population is 1,000 to the acre and that the greatest density of population in the most densely populated part of Bombay is but 759 to the acre, in Prague 485 to the acre, in Paris 434, in London 365, in Glasgow 350, in Calcutta 204, gives one no adequate realization of the state of affairs. No more does it to say that in many city blocks on the East Side there is often a population of from 2,000 to 3,000 persons, a population equal to that of a good-sized village. The only way that one can understand the real conditions is to go down into the streets of these districts and see the thousands of persons thronging them and making them impassable.

(Report of the New York City Commission on Congestion and Population, 1911, p. 5)

There were in Manhattan, in 1905, 122 blocks with a density of 750 to the acre, and 30 blocks with a density of 1,000 or over to the acre, counting in the acreage of such blocks one-half of the area of the bounding streets.

(Report of the New York City Commission on Congestion and Population, 1911, p. 7)

In dealing with established conditions of overcrowding, it may be that the only economically sound policy is to promote the removal of part of the population to other areas.

(Regional Survey of New York and Its Environs, Volume II, Population, Land Value and Government. New York,1928, p. 24)

The Evils of High Lot Coverage

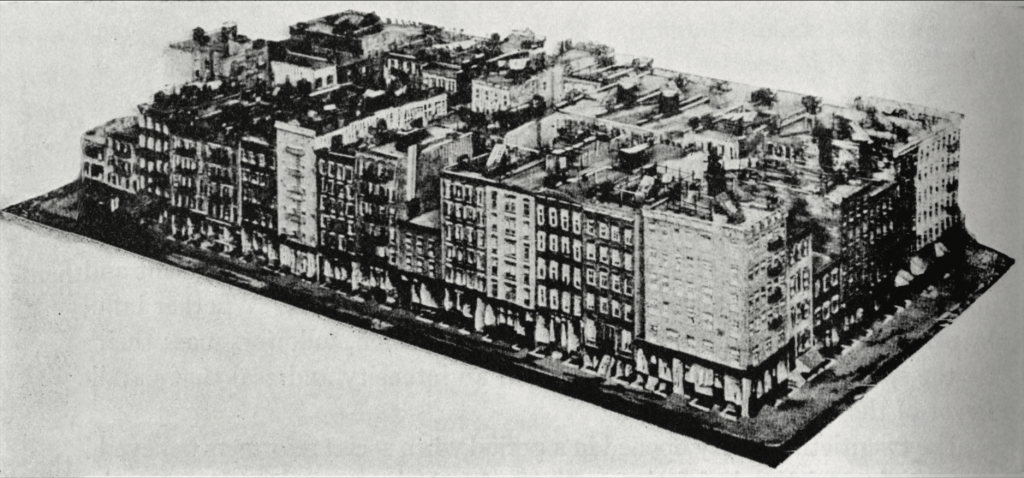

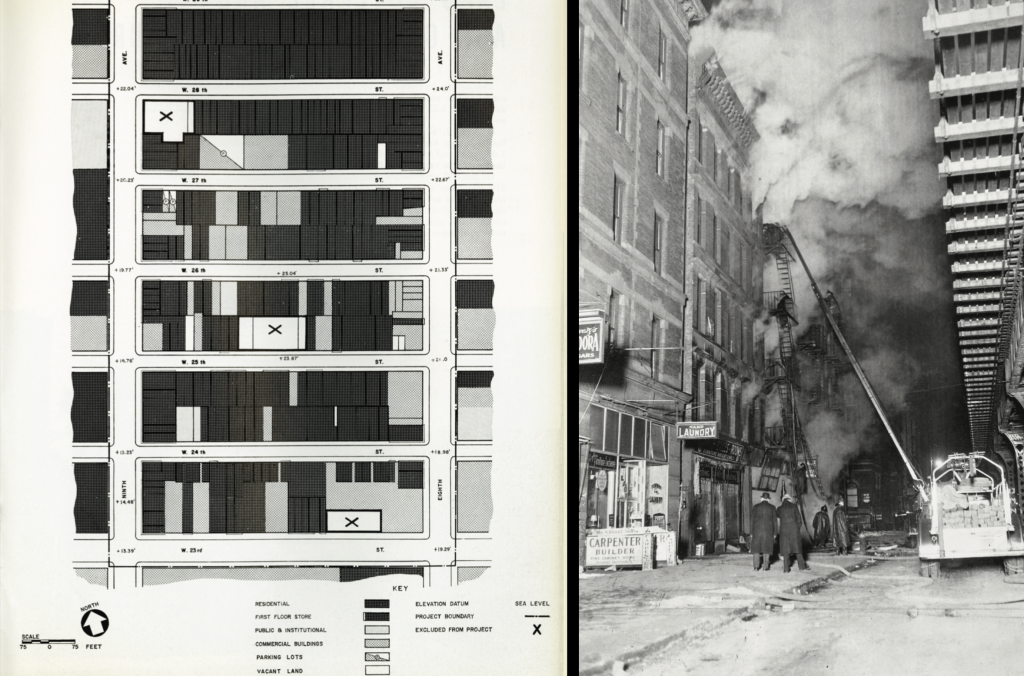

As tenements evolved into 4- or 5-story walkups covering 90 percent of their narrow lots, they aligned to create dense blocks. High ground coverage was a predictable response to Manhattan’s high land costs, but dense tenement districts created sinister conditions. “Slum” problems of crime, disease, and family breakdown resulted from a complex mix of bad-quality housing (windowless rooms, shared toilets, etc.) with social issues of poverty, overcrowding, poor medical care, and exploitative working conditions. Ameliorating slums by upending American capitalism and politics posed a challenge. Lowering ground coverage and mandating higher building standards became, by contrast, an appealing technocratic solution for architects and reformers.

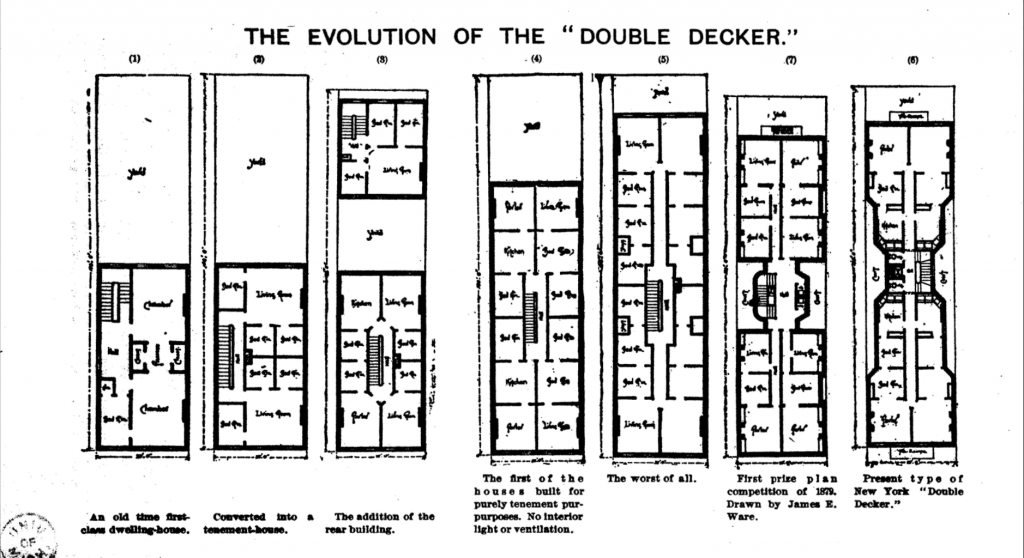

Greedy tenement owners, who had fatally weakened laws passed in 1867 and 1879 helped the reformers’ case. The 1879 law, for instance, had grandfathered in the worst tenements and largely ignored fire safety and sanitation standards of shared hall toilets. The resulting “dumbbell” tenements with their narrow, enclosed airshafts typified the evils of high lot coverage and “slum life.”

The 1901 Tenement House Law, which finally mandated larger lot sizes, courtyards, modern amenities (heat, hot water, larger rooms, and private bathrooms), and included a regulation limiting overcrowding, was a watershed. Still, these “New Law Tenements” – tens of thousands of which rose across the city – could be built at 70 percent coverage on mid-block lots and at 90 percent at corners, but the larger courtyards required demanded they occupy at least two of New York’s narrow lots.

In the minds of the real estate industry and even of many reformers, the New Law Tenement had solved the problems of dense ground coverage by delivering larger light courts, brighter and better ventilated apartments, private sanitary and water facilities, modern heating, and better fire safety. Housing idealists remained unconvinced. To their dismay, many Old Law tenements survived and there were minimal penalties for allowing buildings to rot or remain substandard. New Law tenements also compared unfavorably with garden apartments in Queens and the Bronx, and reformers preferred models of modernist social housing being created in Europe in the interwar years.

In Manhattan over one-fourth of the blocks were covered solidly by buildings or had less than 11 percent of the area not covered and over half of the blocks had less than 21 percent, of the area not covered by buildings.

(Report of the New York City Commission on Congestion and Population, 1911, p. 9)

The most deep-seated evil of the tenement districts in Manhattan lies in the extension of buildings over the rear parts of the lots notwithstanding that much of the rear building was more sanitary and durable than the front building; in other words, in the occupation of space which should never have been built upon. The dark bedroom was the product of this rear building, first beginning with two stories and then gradually raised, often without strengthening of the walls, to five or six stories.

(Regional Survey of New York and Its Environs, Volume VI, Buildings, Their Uses and the Spaces About Them, 1931, p. 125)

(A 1903 report by Robert W. de Forest and Lawrence Veiller) drew attention to the fact that the evils of the tenement houses were primarily “insufficiency of light and air due to narrow courts or air shafts, undue height, the occupation by the building, or by the adjacent buildings, of too great a proportion of the lot areas.” This was put down as the major evil, and the principal recommendation was to correct this evil by new tenements with large courts providing light and ventilation for every room in the buildings. An enormous number of new tenements having more ample light and air than the old tenements have been erected.

(Regional Survey of New York and Its Environs, Volume VI, Buildings, Their Uses and the Spaces About Them, 1931, p. 127)

Abandonment and Decay

In the first four decades of the twentieth century, the city lost 19,000 of its 82,000 old law tenements to abandonment. Some owners evicted tenants and boarded up buildings rather than raise them to 1901 (New Law) or 1929 (Multiple Dwelling Law) health and safety standards. Many owners held onto their derelict properties, despite fines and obsolescence, not only because upgrades were uneconomic, but because they believed future redevelopment would deliver higher prices for the underlying Manhattan land. Added to the old issue of overcrowding, still a serious factor in segregated areas like Harlem, empty tenements often caught fire and threatened lives in adjoining structures. Vermin multiplied in rotting walls and basements. Tenements, in sum, remained a public health issue and impeded general neighborhood improvement.

City leaders had intentionally destroyed tenements during the Great Depression in the name of public health and to make space for civic improvements such as roads, parks, and public housing. Yet tens of thousands of old law tenements survived this civic blitz and remained a crucial piece of the housing market. In 1939, for instance, the 58,000 remaining old law buildings still counted for 38 percent of all city apartments and 2 million poor city residents still inhabited them. Many tenements filled back up during World War II, as well as in and 1950s and Sixties, thanks to the African-American and Puerto Rican migration.

The persistence of squalid, overcrowded tenements remained a broad civic concern during the 1940s and 1950s. Using a mix of city, state, and federal funds—and aggressive implementation of eminent domain—city leaders attacked tenement districts at an unprecedented rate. By the Fifties, however, many began to wonder if the remedy was worse than the disease. Fewer displaced tenement dwellers were rehoused in low-density projects than units were created — raising questions about eliminating even substandard housing without an adequate replacement.

It is safe to say that almost no city needs to tolerate slums. There are plenty of ways of getting rid of them.

Robert Moses (“Slums and City Planning,” The Atlantic, January 1945 Issue)

It is astounding that anyone in local elected or appointed office, anyone with capital and places to risk it, any cooperative group, any prudent conservative bank or loaning agency not compelled to do so, is willing to run the gauntlet and brave the brick bats, rotten eggs and dead cats on the way to slum clearance.

Robert Moses (Speech On Slum Clearance , NYC Municipal Archives WNYC Collection, Apr 17, 1958)

Everybody, it would seem, is for the rebuilding of our cities…But this is not the same as liking cities…most of the rebuilding under way and in prospect is being designed by people who don’t like cities. They do not merely dislike the noise and the dirt and the congestion. They dislike the city’s variety and concentration, its tension, its hustle and bustle. The new redevelopment projects will be physically in the city, but in spirit they deny it – and the values that since the beginning of civilization have always been at the heart of great cities.

William H. Whyte Jr. (included in Roberta Brandes Gratz’s article “Robert Moses Reconsidered: Blight Is in the Eye of the Beholder,” Citylimits.org, April 2, 2007)

No more than 15 percent of those displaced from renewal areas moved into public housing. The rest faced higher rents, and non-whites in particular moved to other slums. Title I aggravated a housing problem by reducing the supply of low-income housing.

Hillary Ballon (included in Roberta Brandes Gratz’s article “Robert Moses Reconsidered: Blight Is in the Eye of the Beholder,” Citylimits.org, April 2, 2007)