New York's History of Slenderness

New York City is the birthplace of the improbably slender tower. In the late 19th- and early 20th century, many tall shafts rose over every square foot of their narrow, high-priced lots. Indeed, it was the high value of the land and

the potential offered by thetechnology of the elevator and steel-cage construction to pile many floors of rentable space onto a small lot that made New York a city of towers.

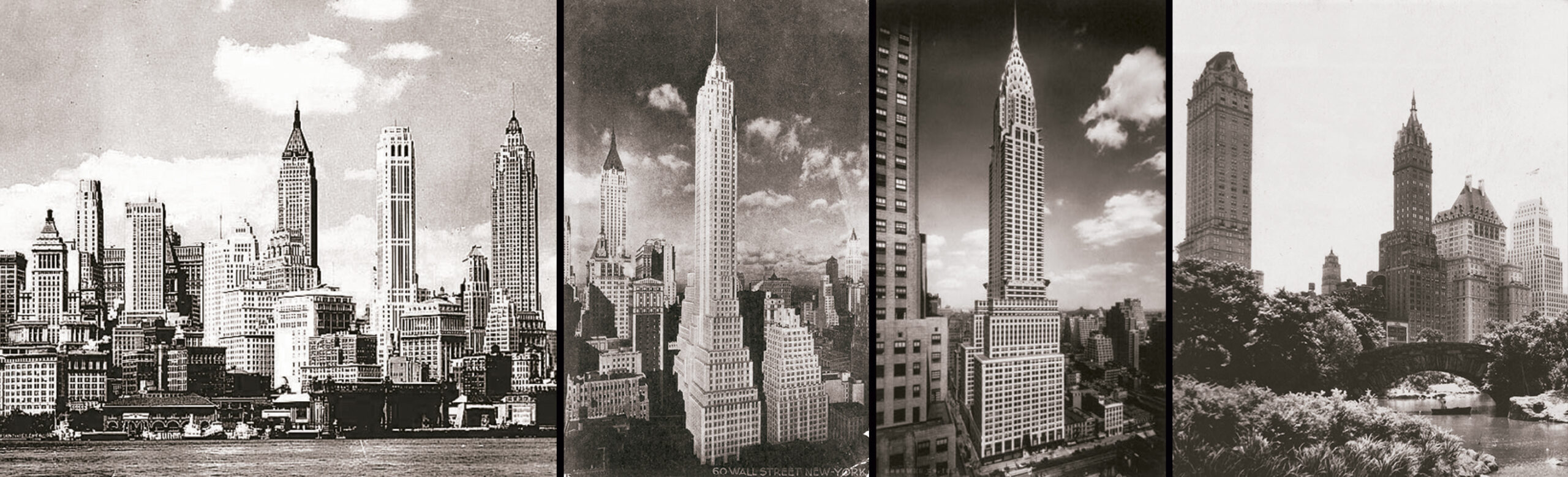

There were three major stages and styles of slenderness in New York's high-rise history. The first was a period of skyrocketing growth when, until the passage of the city's first zoning law in 1916, no municipal regulations

constrained height. By 1909, the Metropolitan Life Insurance Tower rose 700 feet-- 50 stories-- on a lot only 75 x 85 feet. Examples of these laissez-faire structures, spanning 1889-1916 are shown above.

A second phase of vertical ambition and energy came in the 1920s. Shaped by the massing formula set by the 1916 zoning law, buildings with bulky pyramidal bases and slender soaring towers, covering no more than 25 percent of the lot area, became the new characteristic type of New York skyscrapers. Because the 1916 zoning law applied to commercial buildings, including hotels,

in the 1920s, the swank hotels that lined Fifth Avenue at the southeast corner of Central Park could sport tall and slender towers. The Pierre and Sherry Netherland illustrate both the enduring attraction of park views in the luxury life of New York that predict the new residential towers of the twenty-first century.

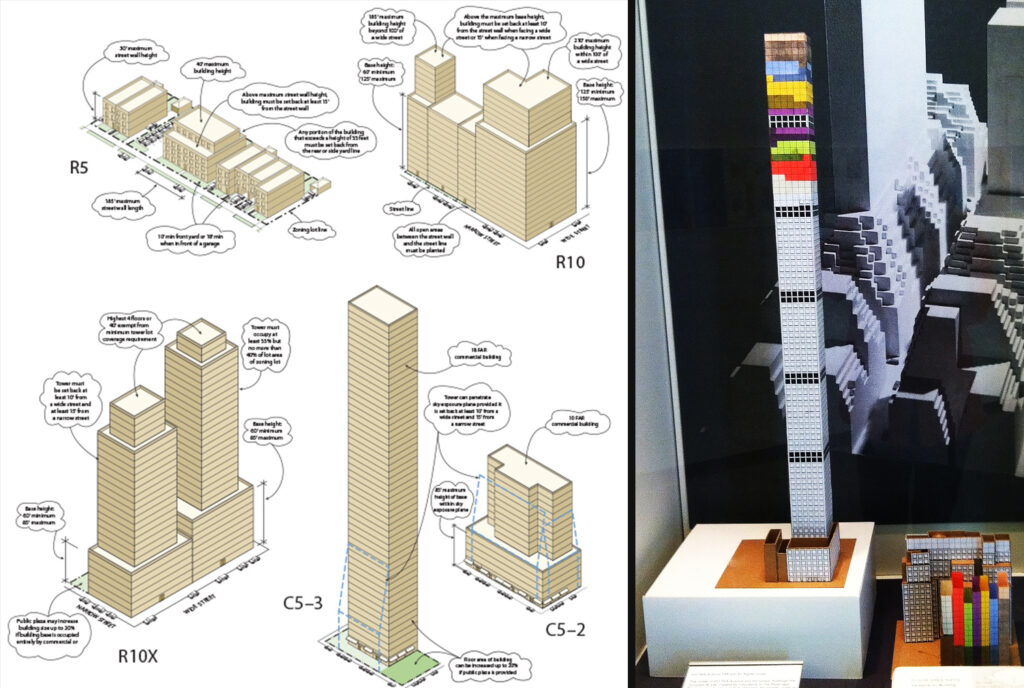

After 1961, a new zoning law set a limit on building height -- or more accurately, imposed a maximum total floor area permitted on a given lot. It introduced a new formula, called the Floor Area Ratio (FAR). A developer can arrange the allowable FAR in any sort of massing, as some variations from the current zoning primer illustrate.

The 1961 law established the principle of “as-of-right,” which allows property owners to design and build whatever they wish without a public review process, so long as they follow zoning rules and do not exceed the maximum FAR allowed for that lot. It also created the concept of air rights, which said that if an existing building has not used all of the FAR allowed that lot, the unused “air rights” could be sold to the owner of an adjacent lot/s and used there. This mechanism, also known as “transferable development rights” (TDRs), lets developers join lots to increase the FAR that can be piled onto a single site.

However, when the underbuilt area of a lot is sold and used on an adjacent site, that low-rise space will then remain open forever. FAR is finite: it can only be used once. TDRs are a cap-and-trade system.

All of the super-slender towers use this method of assembling lots and transferring air rights to consolidate and concentrate their collective FAR into one tall tower. Developers generally demolish the underbuilt structures to create a larger site for their project, even if the tower will cover only a portion. At 432 Park Avenue, for example, the mid-block tower is only 93 feet square and is set back 60 ft. from 56th Street and fronted by a plaza. A low-rise commercial building at the corner creates another zone of open space where the 22-story Drake Hotel once stood.