Timeline of Skyscraper Landmarks by Designation Date

This interactive Timeline presents the buildings chronologically by their designation date and identifies the name, completion date, and architect. Use the cursor to reveal these. The bands below show the administration dates of presiding Mayors and Chairs of the Landmarks Commission.

The names and basic IDs of all the buildings in the Timeline are listed at the end of this page. The IDs are color-coded to denote Downtown buildings (south of 14th St.) in red and Midtown buildings in blue. The few skyscraper Landmarks north of 59th St. are green.

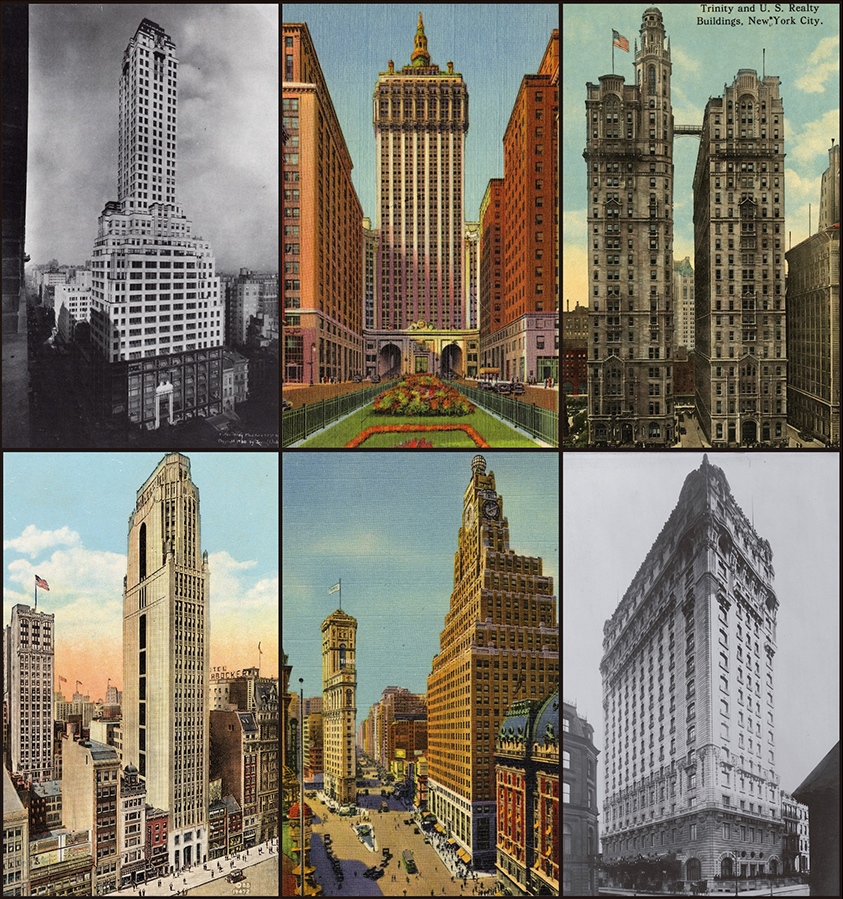

1966-1974, Early Landmarks

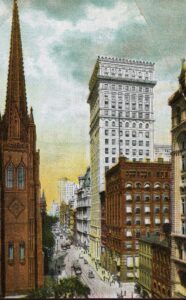

When the new Landmarks Preservation Commission began designating buildings in 1966, it had a list of candidates compiled by the advocates who had pushed for the legislation. Many of those were city-owned properties and thus could be designated without opposition: that explains why the Municipal Building was the first skyscraper protected. Later that year, the Flatiron Building was the first privately-owned skyscraper to be designated, along with three early high-rises that were apartments or hotels. The Woolworth Building was considered at the second public hearing in 1966, but the Commission declined to designate it.

Some extraordinary buildings were lost. In 1969, the Singer Building – tallest in the world when it was completed in 1907 – was demolished to make way for the massive modernist slab of the U.S. Steel Building (One Liberty Plaza). The Commission considered designation, but as then Executive Director of the LPC Alan Burnham explained, “If the building were made a Landmark, we would have to find a buyer for it, or the city would have to acquire it. The city is not that wealthy, and the Commission doesn’t have a big enough staff to be a real-estate broker for a skyscraper.”

The LPC also worried about court challenges to the fundamental constitutionality of the Landmarks Law and was especially anxious about the litigious nature of the real estate industry. In 1967, the Penn Central Railroad sued the City over the designation of Grand Central Terminal – and won. The City appealed, but the legal limbo – which lasted for 12 years, until the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the law on June 26, 1978 – created an unspoken moratorium on designating any skyscrapers. None were proposed from 1969 to 1978, except for the American Radiator Building in 1974.

The American Radiator Building became the second commercial skyscraper to be designated, despite the owner’s objection. The Commission grouped the 1924 office tower in the same hearing with the Interior Landmark of the entrance foyer of the New York Public Library and the Scenic Landmark of Bryant Park – both new categories for the LPC’s protection – to treat them as “an urban ensemble” of aesthetic value.

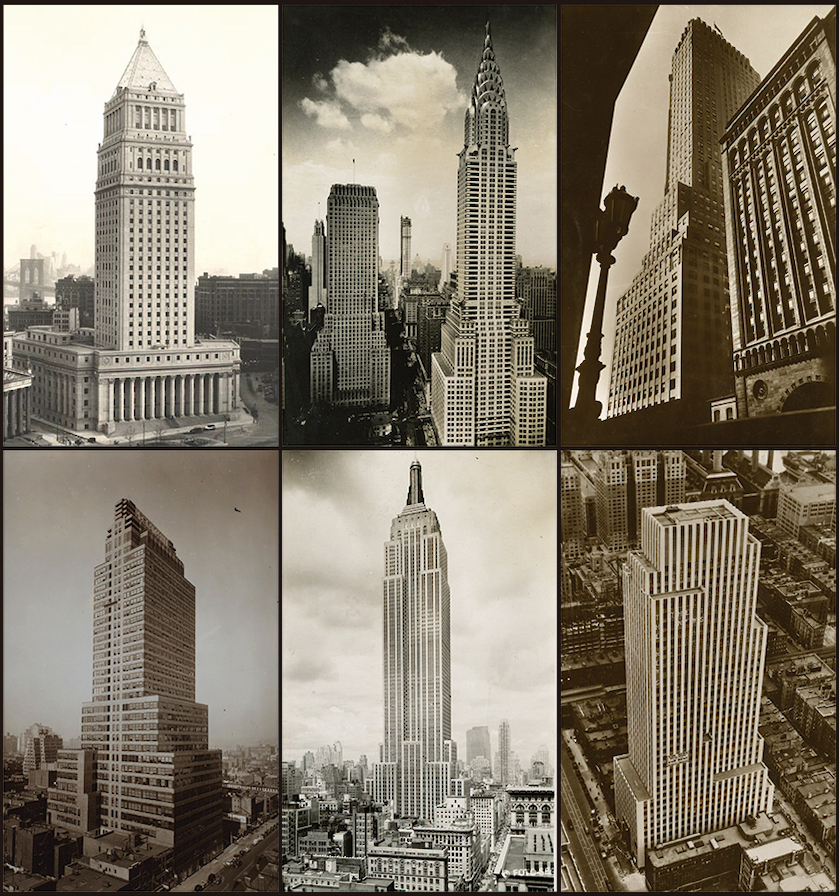

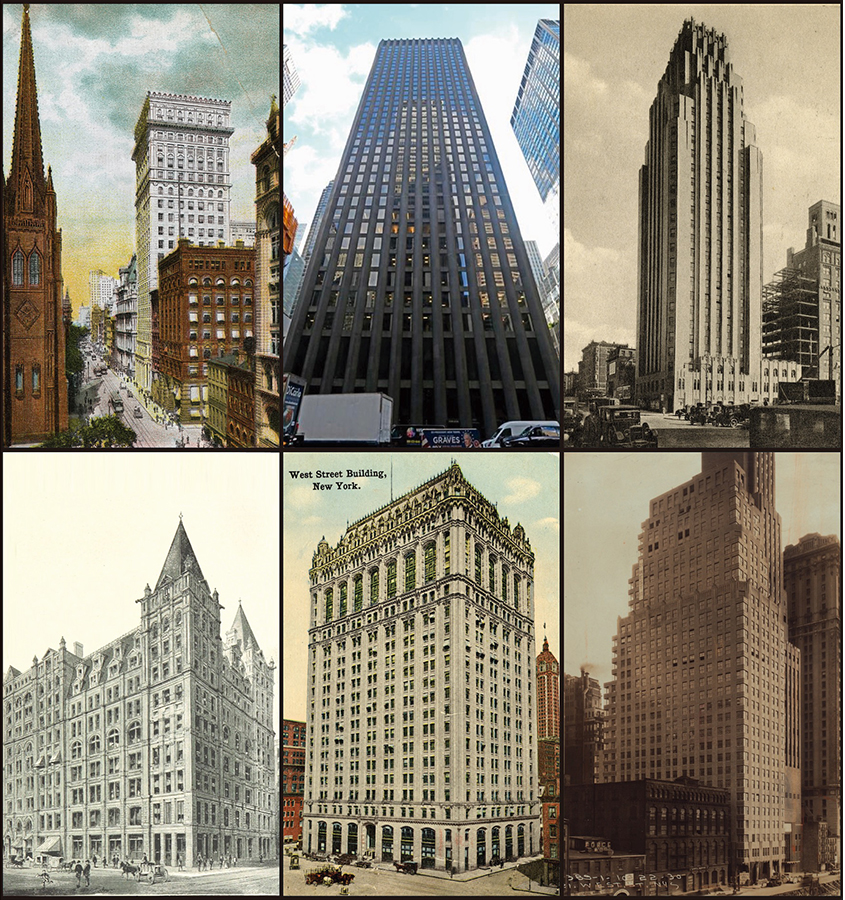

1975-1981, Art Deco Midtown

On September 17, 1974, The New York Times published a short editorial, “No Skyscraper Landmark,” that chided the Commission for its failure to designate “precisely those buildings that are not only New York’s most real and famous Landmarks, but also some of the greatest urban Landmarks of the 20th century – the skyscrapers that are synonymous with the city’s life and style.” Mentioning by name the Woolworth Building, Empire State Building, Chrysler Building, and Rockefeller Center, the author concluded: “These strange omissions are a gargantuan oversight.”

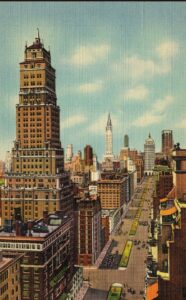

The omissions began to be redressed in 1978 – shortly after the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the Landmarks Law – with a spate of skyscrapers in Midtown. From 1978-1981, the Commission designated five Art Deco icons: the Empire State and Chrysler buildings, as well as a chorus line of towers lining 42nd St. including the Daily News, Chanin, and McGraw-Hill buildings. In the mid-1980s Rockefeller Center, General Electric, and the Fred French Building were protected.

The Art Deco style – which from its appearance in architecture in the mid-1920s had been derided by many critics as a sort of impure modernism that was too decorative and popular – began to receive academic study in the early 1970s. Many warmed to the richness of materials, and palette, and the artistry of the designers and crafts persons who fashioned the ornament. The façades and the lobbies, many of which were also designated as Individual Landmarks, expressed an inventive and distinctive aesthetic of “Machine Age” modernism.

With Kent Barwick as the Chair of the LPC from 1978-1983, appointed by the new Koch administration, the Commission had a leader who had been an advocate and activist for preservation. As the head of the Municipal Art Society (MAS) both before and after his tenure in government, Barwick led protests to save Grand Central, the Broadway theaters and Times Square, and a host of other campaigns.

1982-1986, More Midtown and Lever House

The early Eighties saw a mix of designations under Chairman Kent Barwick that finally checked off some obvious, but recalcitrant candidates, including the Woolworth Building and Rockefeller Center, the LPC also added the first postwar skyscraper to the roster.

In November 1982, the Commission voted unanimously to designate Lever House, the 24-story glass box that in 1952 had introduced a new era and sensibility to Park Avenue, then largely a corridor of stately residential co-ops. As the short skyscraper turned 30, and thus was eligible for protection, the Commission cited it as “among the first, as well as the most famous, corporate expressions of the modern International Style in postwar America.”

But the vote of eleven Commissioners had to be approved by the Board of Estimate, a now-defunct entity replaced by City Council approval. There the designation slammed into both politics and a high stakes Monopoly game of New York real estate. Partial owners of the property, the Fisher Brothers, who preferred to develop a new and larger building on the site, sued to stop the process. Weighing many factors for the future of the city, as well as other pressures, eventually, on January 27, 1983, the Board of Estimate upheld the designation.

The Woolworth Building was designated both an Individual Landmark and Interior Landmark for its lobby on April 12, 1983, seventy years after its 1913 opening as the world’s tallest building. First proposed in 1967, Woolworth received a second hearing in 1970, but the Commission again took no action because the owner opposed designation. A major issue was their objection to LPC oversight over restoring the tower’s elaborate terra-cotta façade. An urgent restoration had been undertaken in 1977 using cast concrete panels, beginning a long history of experiments that continue to today, although now under the review of the LPC.

1985-1988, Upper West Side Art Deco

Another LPC initiative of the mid-1980s, under Chair Gene Norman, was the expansive Central Park West and Riverside-West End Historic Districts, which ultimately covered the majority of the Upper West Side and embraced more than 2000 buildings, nearly all residential. Before the Historic Districts were designated, though, a special group of Art Deco apartment buildings – the Century, Eldorado, Normandy, San Remo, Beresford, and Majestic – were made Individual Landmarks.

Unusually, requests for designation came from groups of residents alarmed by the buildings’ plans to destroy the original, leaking casement windows. Their urgent appeals received quick results by the Commission which calendared the buildings and in the case of the Normandy designated the building at its first public hearing – thus requiring any further changes be reviewed by the LPC.

The twin-towered Century, Eldorado, San Remo, and Majestic, as well as the more cliff-like character of the Beresford or Normandy on Riverside Drive, represent a distinctive type of apartment block massing that came into being after the passage of the 1929 Multiple Dwelling Law. Amending the old code that capped residential construction at a maximum height of 150 feet, the new law allowed apartment buildings on large lots sited on 100-foot avenues to rise to 300 feet to become true skyscrapers.

1986-1988, Mostly Midtown

In the later 1980s a miscellaneous list of high-rise designations continued under Gene Norman, the first Chair to serve as a full-time, full-salary Chairman. Norman focused on the operations of the agency, both for its internal processes and its responsiveness in reviewing applications. By 1988, the scope of the regulatory work and the number of properties that needed alterations that required review by the LPC in public hearings was greatly expanded. As The New York Times real estate reporter Alan S. Oser wrote in 1988:

“Landmarking designations, historic-district designations and interior-Landmark designations have blossomed ever since the Supreme Court decision. There were only 400 individually Landmarked buildings 10 years ago. Today there are 800. There were 31 historic districts then. Today there are 52. There are also 76 interior Landmarks today, many of them recently designated in Manhattan’s legitimate theaters.”

The huge Historic Districts encompassing (dozens of) residential blocks on the both the Upper East Side and Upper West Side consumed much of the agency’s energy — especially with mundane issues of new window applications and minor violations.

At the same time, important older buildings and even designated Landmarks were threatened by rampant high-rise development. A major case was the proposal to demolish the community house adjacent to St. Bart’s (St. Bartholomew’s Episcopal Church) on Park Avenue to construct a 60-story speculative office tower. Litigation ensued, but as with the Grand Central case, the court decision ultimately reinforced the power of the Landmarks Commission.

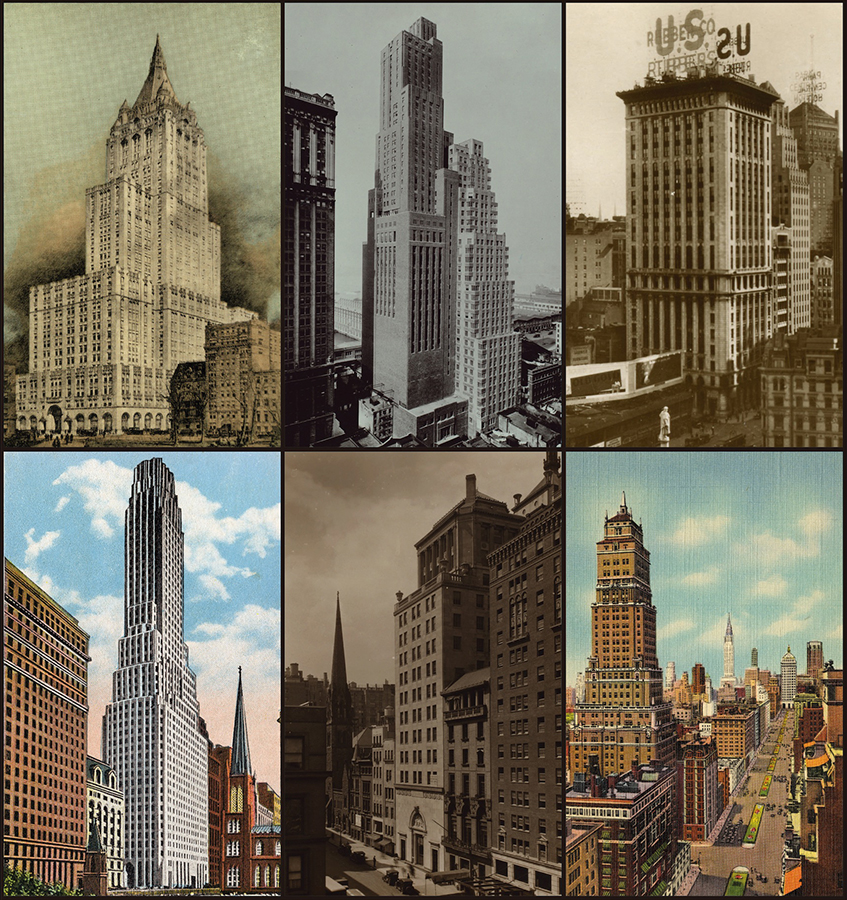

1989-1991, Seagram and the Tilt to Downtown

From its completion in 1958, the sublime Seagram Building, designed by the German-born Bauhaus émigré Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, was the skyscraper that epitomized the values of high-brow, high Modernism known as the International Style. It was designated on October 3, 1989, soon after it turned 30 years old and became eligible for Landmarking. Built as the headquarters for the successful Canadian liquor company Seagram, the 38-story tower was a minimalist glass box articulated by spare bronze I-beam mullions and set back from Park Avenue like a temple on a podium base with a plaza forecourt. Seagram’s welcomed the Landmark status and had even proposed its protection to the Commission in 1976.

This group of six also reveals the beginning of the tilt of the LPC’s focus to Downtown designations. The first group was a trio of massive buildings constructed in the 1920s for the telecommunications companies, AT&T and Western Union. They contained both offices and mechanical operations. Designated on the same day, October 1, 1991, under LPC Chair Laurie Beckelman, all three were designed by Ralph Walker, a master of the “setback style” that was shaped by the requirements of the city’s 1916 zoning law.

In particular, the Barclay-Vesey Building, designed in 1924 and completed in 1926, was one of the earliest and most influential in the evolution of what many architects and writers of the day called the “New Architecture.” Eschewing historical styles, Walker emphasized the power of simple, sculptural masses and applied surface ornament in modernistic motifs that today we call Art Deco. On 9/11, the Barclay-Vesey Building, which stood just north of Tower 1 of the World Trade Center, was severely damaged by its collapse. In 2005, a $322 million restoration project was completed. But the building again suffered damages from flooding during Hurricane Sandy in 2012. Over the decades, all three Walker buildings have undergone renovations to modernize their 1920s telecommunications services. In 2016, the Barclay-Vesey Building, also known as 140 West Street, was converted to luxury condominiums on the upper floors and its Landmarked lobby was gloriously restored.

1991-1995, Downtown

Lower Manhattan became the almost exclusive focus of the Commission’s efforts from 1994 to 2001 under Chair Jennifer Raab, who succeeded Laurie Beckelman as the Chair of the LPC when the Giuliani administration took office in 1994. The LPC designated 24 Individual Landmarks, 17 of which were skyscrapers, as well as the Stone Street Historic District. Building owners in the Financial District had long resisted LPC regulation, which they regarded as a threat to their control over their property and to the potential for turning smaller, older buildings into larger future building sites.

But in the real estate slump of the early-to-mid-1990s, arguments for Landmark designation had a new logic. The impetus to convert Downtown’s older office buildings to residential use began in the mid-1990s for a host of reasons. The stock market crash of 1987 and the savings-and-loan crisis brought a recession to New York commercial real estate markets that by mid-decade had produced a vacancy rate above 30 percent and left 25 million sf. of office space unrented.

The City began to put in place policies that incentivized the restoration and interior upgrades of older office buildings, as well as their conversion to residential use. Buildings that were designated NYC Landmarks or were added to the National Register were further eligible for federal historic preservation tax credits, as well as for City tax breaks. Thus, Landmark designation became an aspect of an economic development strategy and set of policies, as well as a planning tool to transform Downtown into a more vibrant, mixed-use neighborhood with a growing residential population.

1995-1997, More Downtown

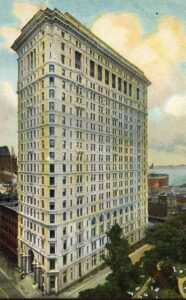

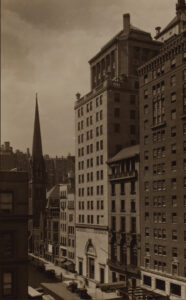

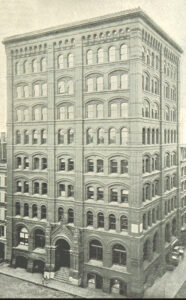

The first of the Downtown designations under Chair Jennifer Raab – a trio of stately office blocks that flanked lower Broadway at Bowling Green – were designated on the same day: September 19, 1995. The headquarters of John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Company at 26 Broadway faced the Cunard Building, the flagship of the transatlantic ocean liner empire. These classically inspired, limestone-clad cliffs shaped the southern end of the urban canyon that stretched north to Wall Street and beyond to City Hall Park. The earliest of the trio, the Bowling Green Building at 5-11 Broadway, was one of the largest office buildings in the city when completed in 1898 and contained some 6,000 tenants. A purely speculative commercial building, it represented the high-rise type of the era before the city’s first zoning law in 1916 required setbacks at upper levels.

Today, these three buildings remain offices by use. When The New York Times reporter David Dunlap wrote “Bringing Downtown Back Up” on Oct. 15, 1995, it was the general assumption that older buildings in the Financial District would be renovated, not converted. Yet, Dunlap added, “Whether visionary or delusional, the possibility is also being explored of converting some distinguished but obsolete office towers into apartment buildings; cliff dwellings and aeries that would appeal to the same pioneering spirit that colonized SoHo and TriBeCa.”

Of the six buildings in this frame, three are still office buildings: 40 Wall St., the Equitable Building at 120 Broadway, and the Bankers Trust Building. The others were converted to apartments – the 57-story City Bank-Farmers Trust, now called 20 Exchange Pl., in phases from 2006-2015, and the Empire Building, just south of Trinity Church, in 1997. An early Park Row high-rise, the ornate 1886 Potter Building, pioneered the transformation of office buildings to lofts when it was converted to cooperative apartments in 1981.

1997-1998, More Downtown and CBS

The campaign of Downtown designations continued under Chair Jennifer Raab from 1995 through 2001, with fourteen more skyscrapers added to the roster of Individual Landmarks, as well as, in June 1996, the Stone Street Historic District. Stone Street was a block of modest low-rise, early-19th century commercial buildings that became the focus of a historic preservation project championed by the Business Improvement District, the Downtown Alliance. It also had an economic development goal of bringing restaurants and lively street life to the area of previously derelict buildings.

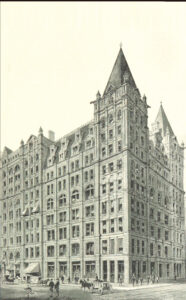

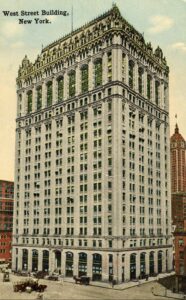

Notable in this group of six is the West Street Building, a 1907 Gothic terra-cotta tower designed by architect Cass Gilbert before he conceived the Woolworth Building. The structure at 90 West Street, just south of the South Tower of the World Trade Center, remained an office building until September 11, 2001, when it was nearly destroyed by the collapse of Tower 2 and burned from fires inside. In 2005, it was completely restored – including with new ornamental terra-cotta – and converted to rental apartments.

Also, in October 1997, the CBS headquarters, known as Black Rock, followed Lever House and the Seagram Building as the third postwar office building to be designated.

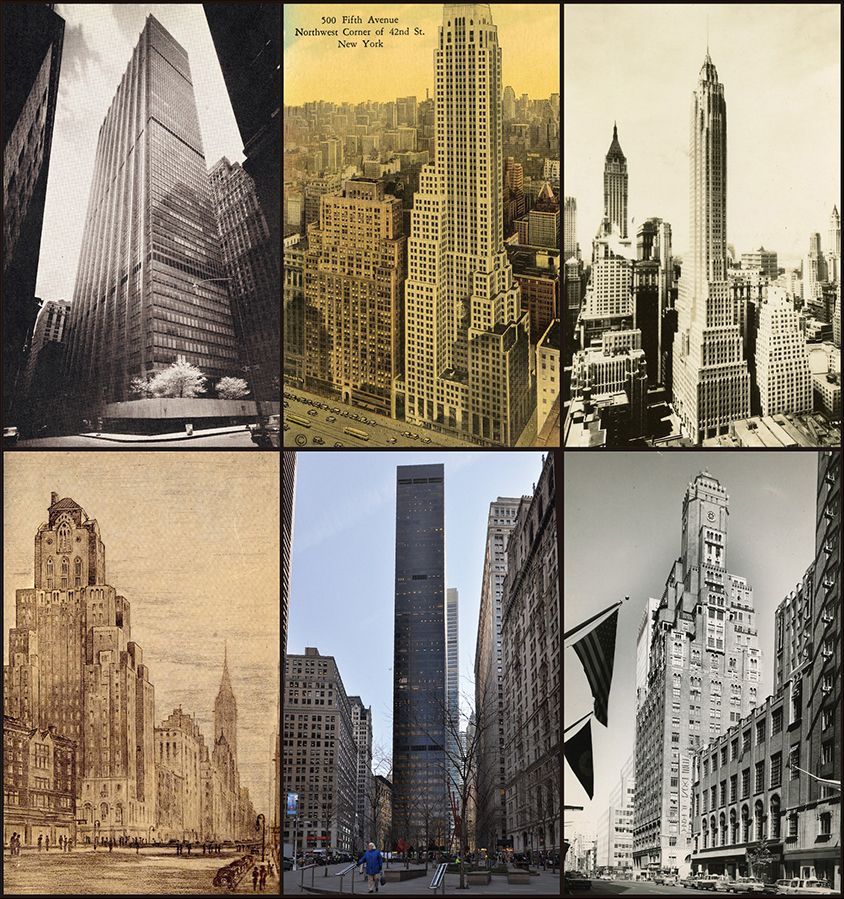

1998-2000, More Downtown

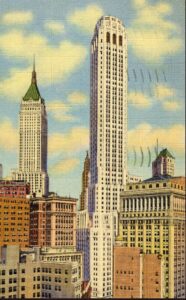

By 2000, the densest concentration of Individual Landmarks in the city (with the exception of the three full blocks of Rockefeller Center) was Downtown, focused especially in the core of the Financial District, lining Broadway, and surrounding City Hall Park.

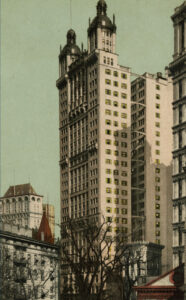

Of the six buildings in this group, three are early skyscrapers associated with “Newspaper Row,” the moniker of Park Row from the mid-19th century when dozens of dailies and national magazines published and printed their papers in the area. In order of age, they are G.B. Post’s New York Times Building (1889), the American Tract Society Building (1895), and the Park Row Building (1899), which on its completion in 1899 was the world’s tallest office building at 391 feet. While the former New York Times Building has served as classrooms and offices for Pace University since 1951, the other two structures were more recently converted to apartments: the Park Row Building began with the upper floors in 2001, then fully in 2018, and the American Tract Society Building in 2003. Similarly, 25 Broad St. was transformed into rental apartments in 1997, as was the Whitehall Building on Battery Place in 1999.

2000-2002

Two more significant Downtown skyscrapers were designated in 2000-2001. One was the Downtown Athletic Club, a restrained red brick Art Deco tower by architects Starrett & Van Vleck, which had housed athletic activities, dining rooms, and residential quarters. The other was 1 Wall Street, the most elegant skyscraper designed by Ralph Walker, originally erected as the headquarters of the Irving Trust Bank.

Between 2000-2002, three Midtown buildings of the Twenties were added to the roster. The New York Life Insurance Building, designed by Cass Gilbert as a Gothic-inspired setback tower and clad in limestone, rather than Woolworth’s terra-cotta, rose over a full block at the northeast corner of Madison Square Park, on the former site of Madison Square Garden. On W. 57th St., the former Steinway Hall was classical and reserved, while the Ritz Tower on E. 57th St. had a chateauesque silhouette that matched the other swank apartment hotels of the period, such as the Sherry Netherland and Pierre.

2003-2009

After 9/11 and in 2002 when the Bloomberg administration began its three-term tenure with Robert Tierney as the new Chair, the pace of protection for skyscrapers slowed. Whereas Raab’s LPC had designated twenty-four buildings in seven years, from 2003-2013 only twelve were added. As the next two groups of images illustrate, the tall buildings Landmarked represented an eclectic mix of geography, eras, and styles.

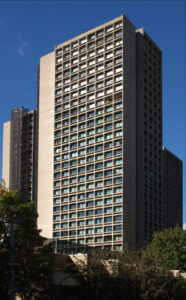

Two postwar projects are notable. The Socony-Mobil Building at the corner of Lexington and 42nd St., completed in 1956, is an oddball skyscraper by Harrison & Abramowitz that features a façade of pleated chromium nickel panels embossed with geometric designs and relatively small window openings in the curtain wall. The second is a trio of apartment blocks known as University Village or Silver Towers, designed by I.M. Pei & Associates and completed in 1967. They were engineered and erected in an innovative system of concrete construction that expressed the raw surface of the material as part of the modernist and minimalist aesthetic.

2009-2016

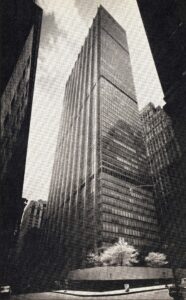

In the third term of the Bloomberg administration from 2009-2013, one skyscraper was designated per year, with a balance between Midtown and Downtown. Two in Lower Manhattan were outstanding postwar office towers, exemplars of International Style Modernism designed by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM): One Chase Manhattan Plaza, built from 1957-1964, and the Marine Midland Building at 140 Broadway, completed in 1968. The first major office building erected in the Financial District after WWII, One Chase Manhattan Plaza was a key investment by the Bank and its powerful president David Rockefeller, signing a commitment to maintaining its headquarters Downtown. Likewise, the sleek glass-box of the Marine Midland Building — rising as a sheer slab in a large plaza — brought ultra-modern office space to lower Broadway.

The other four skyscrapers in this group were handsome towers of the Twenties, including the Cities Service Building at 70 Pine St., with its sumptuous Art Deco ornament at the street level and in its Landmarked lobby. In Midtown, two residence hotels, the Barbizon Hotel for Women and the Beverly, both from 1927, evidenced the development opportunities around Grand Central Terminal.

2016-2018

Under the new de Blasio administration in 2014 and a new Chair Meenakshi Srinivasan, the push to upzone the blocks around Grand Central, initiated by City Planning in the last Bloomberg years, was accomplished. The idea was to maintain the competitive advantage of Midtown’s transportation nexus by allowing greater density in new towers than was possible under the old code. The broad planning and economic development goal of East Midtown Rezoning required the collaboration and compromise of many interest groups.

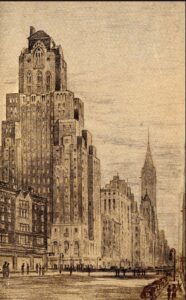

Preservationists leveraged the opportunity to win the designation of five skyscrapers in 2016, which were part of fifteen new Landmarks in the district. These included the Shelton and Lexington hotels and the Graybar Building, as well as the Citicorp Center. Completed in 1978, the sleek white Citicorp had an elegant geometry in its square shaft and slanted top, that affirmed the values of modernism. By contrast, the AT&T Building at 550 Madison, completed in 1984, was intended to shock. Architect Philip Johnson divided the critics with his design for “the first Postmodern skyscraper.” In 2018, after an activist campaign, the building, now called by its address 550 Madison, was designated. The final image in the group is the Williamsburgh Savings Tower in Brooklyn, designated in 1977, which fills out the frame and points to a group of high-rises in Brooklyn Downtown that are protected as part of a Historic District, but are not Individual Landmarks.

1966-1974, Early Landmarks

1

Municipal Building, 1909-1914

1 Centre St.

Architect: McKim, Mead & White

Designation: February 1, 1966

2

Hotel Chelsea, 1883-1885

222 West 23rd St.

Architect: Hubert, Pirsson & Co.

Designation: March 15, 1966

3

Flatiron Building, 1902-1903

175 Fifth Ave.

Architect: D. H. Burnham & Co.

Designation: September 20, 1966

4

Plaza Hotel, 1905-1907

768 Fifth Ave.

Architect: Henry Hardenbergh

Designation: December 9, 1969

5

Ansonia Hotel, 1899-1904

2101-2119 Broadway

Architect: Paul E. M. DuBoy

Designation: March 14, 1972

6

American Radiator Bldg, 1923-1924

40 West 40th St.

Architect: Raymond M. Hood

Designation: November 12, 1974

1975-1981, Art Deco Midtown

7

U.S. Courthouse, 1933-1936

40 Centre St.

Architect: Cass W. Gilbert

Designation: March 25, 1975

8

Chrysler Building, 1928-1930

405 Lexington Ave.

Architect: William Van Alen

Designation: September 12, 1978

9

Chanin Building, 1927-1929

122 East 42nd St.

Architect: Sloan & Robertson

Designation: November 14, 1978

10

McGraw-Hill Building, 1930-1931

330 West 42nd St.

Hood, Godley & Fouilhoux

Designation: September 11, 1979

11

Empire State Building, 1929-1931

20 West 34th St.

Architect: Shreve, Lamb & Harmon

Designation: May 19, 1981

12

Daily News Building, 1929-1930

220 East 42nd St.

Architect: Raymond M. Hood

Designation: July 28, 1981

1982-1986, Midtown & Lever House

13

Liberty Tower, 1909-1910

55 Liberty St.

Architect: Henry Ives Cobb

Designation: August 24, 1982

14

Lever House, 1950-1952

390 Park Ave.

Architect: SOM

Designation: November 9, 1982

15

Woolworth Building, 1911-1913

233 Broadway

Architect: Cass W. Gilbert

Designation: April 12, 1983

16

Rockefeller Center, 1932-33

RCA Bldg, 30 Rockefeller Plaza

Assoc. Arch. of Rockefeller Cntr

Designation: April 23, 1985

17

General Electric Building, 1929-1931

570 Lexington Ave.

Architect: Cross & Cross

Designation: July 9, 1985

18

Fred F. French Building, 1926-1927

551 Fifth Ave.

H. D. Ives, Sloan & Robertson

Designation: March 18, 1986

1985-1988, Upper West Side Art Deco

19

Century Apartments, 1931

25 Central Park West

Architect: Irwin S. Chanin

Designation: July 9, 1985

20

Eldorado Apartments, 1929-1931

300 Central Park West

Architect: Margon & Holder w/ E. Roth

Designation: July 9, 1985

21

Normandy Apartments, 1938-1939

140 Riverside Drive

Architect: Emery Roth & Sons

Designation: November 12, 1985

22

San Remo Apartments, 1929-1930

145-146 Central Park West

Architect: Emery Roth

Designation: March 31, 1987

23

Beresford Apartments, 1928-1929

211 Central Park West

Architect: Emery Roth

Designation: September 15, 1987

24

Majestic Apartments, 1930-1931

115 Central Park West

Architect: Irwin S. Chanin

Designation: March 8, 1988

1986-1988, Mostly Midtown

25

Fuller Building, 1928-1929

595 Madison Ave.

Architect: Walker & Gillette

Designation: March 18, 1986

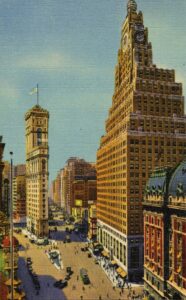

26

New York Central Bldg, 1927-1929

230 Park Ave.

Architect: Warren & Wetmore

Designation: March 31, 1987

27

111 & 115 Broadway, 1905 & 1907

111 & 115 Broadway

Architect: Francis Hatch Kimball

Designation: June 7, 1988

28

Bush Tower, 1916-1918

130 West 42nd St.

Architect: Helmle & Corbett

Designation: October 18, 1988

29

Paramount Building, 1926-1927

1501 Broadway

Architect: Rapp & Rapp

Designation: November 1, 1988

30

St. Regis Hotel, 1901-1904

2 East 55th St.

Arch.: Trowbridge & Livingston

Designation: November 1, 1988

1989-1991, Seagram & Downtown

31

Metropolitan Life Ins. Co, 1907-9

1 Madison Ave.

Arch.: Napoleon LeBrun & Sons

Designation: June 13, 1989

32

Seagram Building, 1955-1958

375 Park Ave.

Architect: Mies w/ Philip Johnson

Designation: October 3, 1989

33

Master Building, 1928-1929

310 Riverside Dr.

Architect: Harvey Wiley Corbett

Designation: December 5, 1989

34

Barclay-Vesey Building, 1923-27

140 West St.

Architect: Ralph Walker

Designation: October 1, 1991

35

Long Distance Bldg, 1930-31

32 Sixth Ave.

Architect: Ralph Walker

Designation: October 1, 1991

36

Western Union Bldg, 1928-30

60 Hudson St.

Architect: Ralph Walker

Designation: October 1, 1991

1991-1995, Downtown

37

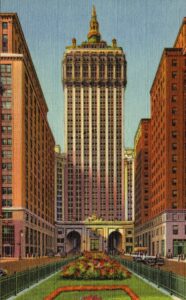

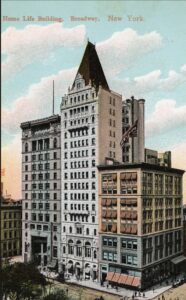

Home Life Building, 1892-1894

253-257 Broadway

Arch.: G. E. Harding and Gooch

Designation: November 12, 1991

38

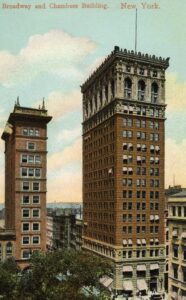

Bway-Chambers Bldg, 1899-1900

277 Broadway

Architect: Cass W. Gilbert

Designation: January 14, 1992

39

Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, 1929-1931

301 Park Ave.

Architect: Schultze & Weaver

Designation: January 5, 1993

40

Bowling Green Off. Bldg, 1895-98

5-11 Broadway

Architect: W. & G. Audsley

Designation: September 19, 1995

41

Cunard Building, 1920-1921

25 Broadway

Architect: Benjamin Wistar Morris

Designation: September 19, 1995

42

Standard Oil Building, 1921-1928

26 Broadway

Architect: Carrère & Hastings

Designation: September 19, 1995

1995-1997, More Downtown

43

Manhattan Co. Bldg, 1929-1930

40 Wall St.

Architect: H. Craig Severance

Designation: December 12, 1995

44

City Bank-Farmers Trust, 1930-31

20 Exchange Pl.

Architect: Cross & Cross

Designation: June 25, 1996

45

Empire Building, 1897-1898

71 Broadway

Arch.: Kimball & Thompson

Designation: June 25, 1996

46

Equitable Building, 1913-1915

120 Broadway

Arch.: Graham w/ Anderson

Designation: June 25, 1996

47

Potter Building, 1883-1886

35 Park Row

Arch.: N. G. Starkweather

Designation: September 17, 1996

48

Bankers Trust, 1910-1912

14 Wall St.

Arch.: Trowbridge & Livingston

Designation: January 14, 1997

1997-1998, Downtown & CBS

49

American Surety Bldg, 1894-1896

100 Broadway

Architect: Bruce Price

Designation: June 24, 1997

50

CBS Building, 1961-1964

Sixth Ave., 52nd St. to 53rd St.

Architect: E. Saarinen & Assoc.

Designation: October 21, 1997

51

Panhellenic Tower,1927-1929

First Ave. & 49th St.

Architect: John Mead Howells

Designation: February 3, 1998

52

Temple Court Building, 1881-1883

3-9 Beekman St.

Architect: Silliman & Farnsworth

Designation: February 10th, 1998

53

West Street Building, 1905-1907

90 West St.

Architect: Cass W. Gilbert

Designation: May 19, 1998

54

21 West Street Bldg, 1929-1931

21 West St.

Architect: Starrett & Van Vleck

Designation: June 16, 1998

1998-2000, More Downtown

55

Bank of NY & Trust Bldg, 1929-31

48 Wall St.

Architect: Benjamin Wistar Morris

Designation: October 13, 1998

56

New York Times Bldg, 1888-1889

41 Park Row

Architect: George B. Post

Designation: March 16, 1999

57

American Tract Soc. Bldg, 1894-95

150 Nassau St.

Architect: R. H. Robertson

Designation: June 15, 1999

58

Park Row Building, 1896-1899

15 Park Row

Architect: R. H. Robertson

Designation: June 15, 1999

59

Broad Exchange Bldg, 1900-1902

25 Broad St.

Architect: Clinton & Russell

Designation: June 27, 2000

60

Whitehall Building, 1902-1904

17 Battery Pl.

Architect: Henry J. Hardenbergh

Designation: October 17, 2000

2000-2002

61

NY Life Insurance Co., 1926-1928

51 Madison Ave.

Architect: Cass W. Gilbert

Designation: October 24, 2000

62

Downtown Athletic Club, 1929-30

20 West St.

Architect: Starrett & Van Vleck

Designation: November 14, 2000

63

U.S. Rubber Co. Bldg, 1911-1912

1790 Broadway

Architect: Carrère & Hastings

Designation: December 19, 2000

64

Irving Trust/Bank of NY, 1929-31

1 Wall St.

Architect: Ralph Walker

Designation: March 6, 2001

65

Steinway Hall, 1924-1925

111 West 57th St.

Architect: Warren & Wetmore

Designation: November 13, 2001

66

Ritz Tower, 1925-1927

465 Park Ave.

Architect: E. Roth w/ T. Hastings

Designation: October 29, 2002

2003-2009

67

Socony-Mobil Building, 1954-1956

150 East 42nd St.

Harrison & Abramowitz w/ Peterkin

Designation: February 25, 2003

68

AT&T Building, 1912-1916

195 Broadway

Arch.: William Welles Bosworth

Designation: July 25, 2006

69

Morse Building, 1878-1880

138 Nassau St.

Arch.: Silliman & Farnsworth

Designation: September 19, 2006

70

University Village, 1964-1967

110 Bleecker St.

Architect: I.M. Pei & Assoc.

Designation: November 18, 2008

71

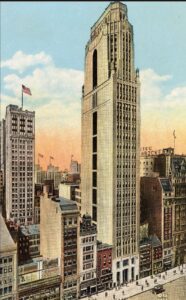

275 Madison Ave. Bldg, 1930-1931

275 Madison Ave.

Architect: Kenneth Franzheim

Designation: January 13, 2009

72

Con. Edison Building, 1910-1911

4 Irving Pl.

Architect: Henry J. Hardenbergh

Designation: February 10, 2009

2009-2016

73

1 Chase Manhattan Plz, 1957-1964

28 Liberty St.

Architect: SOM

Designation: February 10, 2009

74

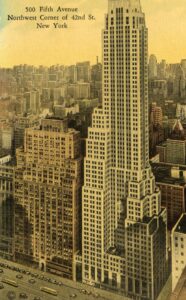

500 Fifth Ave. Building, 1929-1931

500 Fifth Ave.

Arch.: Shreve, Lamb & Harmon

December 14, 2010

75

Cities Service Building, 1930-1932

70 Pine St.

Clinton & Russell, Holton & George

Designation: June 21, 2011

76

Barbizon Hotel for Women, 1927-28

140 East 63rd St.

Architect: Murgatroyd & Ogden

Designation: April 17, 2012

77

Marine Midland Bldg, 1964-1968

140 Broadway

Architect: SOM

Designation: June 25th, 2013

78

Beverly Hotel, 1926-1927

125 East 50th St.

Architect: Emery Roth

Designation: November 22, 2016

2016-2018

79

Shelton Hotel, 1922-1923

525 Lexington Ave.

Architect: Arthur Loomis Harmon

Designation: November 22, 2016

80

Hotel Lexington, 1928-1929

511 Lexington Ave.

Architect: Schultze & Weaver

Designation: November 22, 2016

81

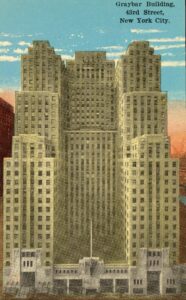

Graybar Building, 1925-1927

420 Lexington Ave.

Architect: Sloan & Robertson

Designation: November 22, 2016

82

Citicorp Center, 1973-1978

601 Lexington Ave.

Hugh A. Stubbins w/ E. Roth & Sons

Designation: December 6, 2016

83

AT&T Building, 1978-1984

550 Madison Ave.

Architect: P. Johnson & J. Burgee

Designation: July 31, 2018

84

Williamsburgh Savings, 1927-28

1 Hanson Place, Brooklyn

Halsey, McCormack & Helmer

Designation: November 15, 1977