Municipal Building, 1909-1914

1 Centre St.

Architect: McKim, Mead, and White

Designation: February 1, 1966

Flatiron Building, 1902-1903

175 Fifth Ave.

Architect: D. H. Burnham & Co.

Designation: September 20, 1966

EARLY LANDMARKS

The First Skyscraper Designations

When the nascent Landmarks Preservation Commission began designating buildings in 1966, it had a list of candidates compiled by advocates and architectural historians who had long pushed for the legislation. The earliest and easiest designations were city-owned properties. The Municipal Building was the first skyscraper to be protected on February 1, 1966. Later that year, the Flatiron Building became the first privately-owned skyscraper to become a Landmark.

Early Designation Reports were very short, with inexplicit descriptions: for example, the Flatiron Building possessed a “special character” and “poetic quality.” Considerable space was devoted to reassuring the owners that the LPC would not overreach: “By this designation it is not intended to freeze the Flatiron Building in its present state for all time and thus prevent future appropriate alterations at street level. The Commission believes it has the obligation, and indeed, it has the desire, to cooperate with owners of Landmarks who may wish to make changes in their properties to meet their current and future needs.”

Until the Supreme Court upheld the Landmarks Law in 1978, the Commission was timid with regard to commercial architecture: no skyscraper office buildings were designated except the American Radiator Building in 1974.

THE WOOLWORTH BUILDING

The Woolworth Building cut a fine silhouette on the skyline in 1913 when its Gothic spire earned it the title "the Cathedral of Commerce." But on close examination, its ornate terracotta façade had problems even before completion. Affixing the intricate 3-D puzzle of glazed terracotta – baked earth – to the steel frame of the world's tallest building resulted in cracks and sealant issues that have plagued the building through the decades.

Various façade repair and replacement strategies were attempted, including in 1978 cast concrete tiles that later discolored, creating a scabrous texture. Although the building had been considered for Landmark status in 1966, and then again in 1970, the Commission declined to designate it, principally because of owner opposition to the LPC's oversight of façade work. Also in 1978, the badly deteriorated tourelles, the four small towers flanking the spire, were replaced with pressed aluminum with a geometric-pattern that very loosely resembled the original silhouette and color scheme.

The Woolworth Building was finally designated in 1983, both as an Individual Landmark and Interior Landmark for its magnificent lobby. All subsequent changes and restoration work have been reviewed by the LPC, including the alterations necessitated by the conversion of the tower section into posh condominium residences. While conversion to new uses is not restricted by the LPC, any changes that are visible from the street must be approved as “appropriate.”

For more content on the Woolworth Building's history and original terra cotta, visit the archived 2013 exhibition "Woolworth @ 100" on the Museum's website.

Hughson Hawley, 1911

In early February 1911, shortly after Cass Gilbert's office finalized the design of the Woolworth Building, they gave their in-house perspective to the noted freelance delineator Hughson Hawley for "coloring." Hawley's version became the definitive image of the tower used in the public relations campaign to draw worldwide attention to the project. Woolworth copyrighted Hawley's painting and on May 4, 1911, distributed a photograph to the press, hoping to capture front-page coverage in the Sunday papers.

Indeed, the drawing spanned three columns on page 1 of The New York Times Real Estate section on May 7th under the headline "Woolworth Building Will Be World's Greatest Skyscraper."

The framed Hawley perspective on the case wall is on loan from a private collection.

PRESERVATION ARCHITECT: Beyer Blinder Belle

CLIENT: Empire State Realty Trust

COMPLETED: 2009

EMPIRE STATE BUILDING, LANDMARK LOBBY RENOVATION

The Museum invited the preservation architect for the Empire State Building, Beyer Blinder Belle, to curate the gallery case that addresses various issues of the restoration work in the Landmarked lobby. They selected the items inside to case and prepared the following label copy to describe the work.

A LOOK INSIDE THE RESTORATION PROCESS

Beyer Blinder Belle (BBB) led a team of architects, historians, artists, and craftsmen in the restoration of the lobby of the Empire State Building, after modifications to the building over time had obscured the grandeur of its original Art Deco design. Following two years of research—including the review of historical documents, photos, sketches, and blueprints, and a forensic analysis of existing architectural elements—BBB returned the lobby to its original vision. The work includes a faithful restoration of a stunning Art Deco ceiling mural, the addition of upgraded technology systems, and improved tenant and visitor services. Concurrent with the lobby restoration, BBB also prepared a Conceptual Master Plan that addresses import-ant planning and design issues throughout the lobby, street entrances, corridors, elevator bank areas, retail spaces, and public floors.

A Respect for History through Research and Collaboration

The challenge of every preservation architect is to strike a successful balance between honoring the historic integrity of a building while making the improvements necessary to meet the needs of modern owners and users. Since the creation in 1965 of the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC), the agency empowered with the designation and protection of the city’s built history, an intensive and carefully coordinated process of restoration design and review has evolved. This process was successfully employed – and enhanced – by the Empire State Building (ESB) lobby restoration completed in 2009.

The success of this restoration process depends on the active contributions and collaboration of three key participants: the building owner, the design team, and the LPC staff reviewers. The ESB lobby project was fortunate to have the enlightened and enthusiastic leadership of Anthony Malkin, CEO of Empire State Realty Trust, owner of the ESB. He provided the support necessary to complete such a complex project, resolving all difficult design decisions by asking, “What would Shreve, Lamb & Harmon do?”

The design team is the next participant, composed of architects, engineers, and specialty consultants who share a common passion for historic architecture and a dedication to the rigorous research required to propose improvements which are informed and appropriate.

The third participant is the LPC itself, an agency staffed by people with similar training and sensibilities as the design team, but charged with the legal responsibility to confirm the accuracy and appropriateness of all proposed changes, improvements, and modifications. Beyer Blinder Belle, the restoration architect for the Empire State Building, has made it a policy to engage LPC staff as early in the design process as possible to share research, discuss design goals, identify challenges, and encourage active feedback. Maintaining active and open communication throughout the design process facilitates a better-informed review period, which contributes to all participants’ shared goal of a historic building for its future – through a thoughtful and enthusiastic celebration of its past.

A Ceiling from an Era of Speed and Machinery

Covered long ago by paint and drop ceilings, the original lobby ceiling mural had become little more than a memory sustained by a few old photographs and a small, exposed area accessible only to the maintenance staff. Through exhaustive research and scientific examination of the original mural, EverGreene Architectural Arts designed, fabricated, and installed an exact recreation using the exact methods and materials from 1931.

The new mural glows with reflected light and depicts a celestial sky reimagined as a constellation of gears and machine components.

The Restoration of Art Deco Ornament

In the early 1960s, eight recessed marble wall niches were removed and replaced with backlit infill acrylic panels depicting the “Eight” Wonders of the World – the well-known seven plus, of course, the Empire State Building. Although popular, the panels were dated and aesthetically inappropriate to the 1930s Art Deco lobby, casting the corridor in a cold blue-green light. The panels were removed to storage, and the niches were recreated in the original manner using identical marble – fortuitously found in a Brooklyn warehouse – with pieces carefully selected, cut, and installed in reflected, or “bookmatched,” arrangements which creatively celebrate the material’s distinctive burgundy veining.

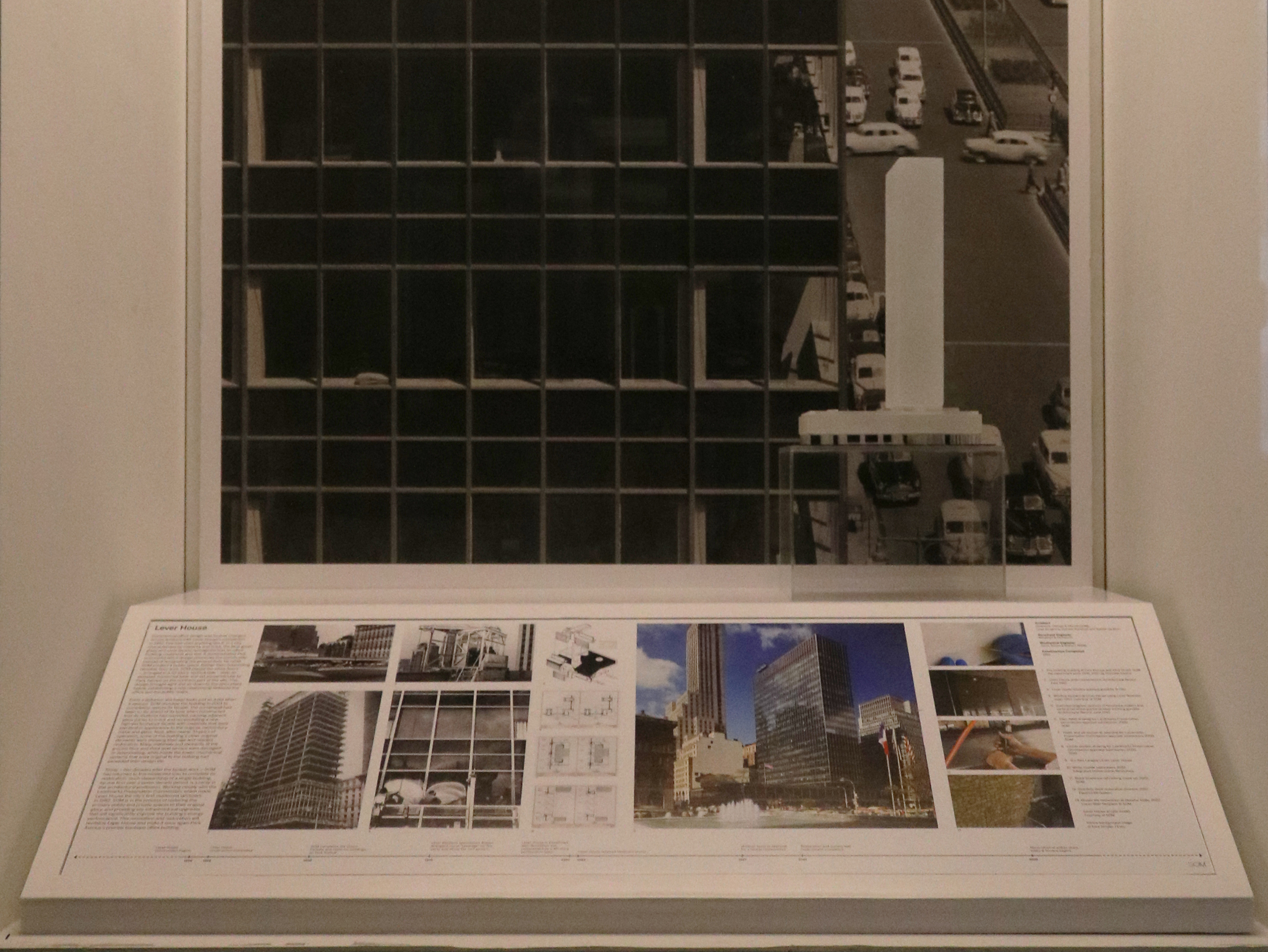

Lever House, 1950-1952

390 Park Ave.

Architect: SOM

Designation: November 9, 1982

LEVER HOUSE

Commercial office design was forever changed across America with Lever House’s completion in 1952. Few had seen anything like it: in a city characterized by masonry and brick, the blue-green glass and steel façade reimagined how an office building could look and feel. It demonstrated that successful office design prioritizes the community; instead of designating the ground floor for retail, SOM created a public space. Rather than maximizing rentable floor area, SOM placed the office floors – arranged in a 22-story, vertical slab – atop an elevated, horizontal base and set perpendicular to Park Avenue on the northern part of the site. This design brought light and air down to the open plaza below, establishing a new relationship between the office and the public realm.

From a distance, the tower looks just as it did when it opened. SOM revisited the building in 2001 to completely restore its façade. The curtain wall had been so far ahead of its time when constructed that its mullions had corroded, causing adjacent glass panes to crack and necessitating a new, high-performance façade with materials that were identical in appearance to the original, mid-century metal and glass. Now, after nearly 70 years of operation, some of the building’s other original elements were showing their age and needed restoration. Many materials and elements at the ground floor and third level terrace were damaged or deteriorating, while inside the tower, mechanical systems that were original to the building had exceeded their design life.

Today – two decades after the façade work – SOM has returned to this modernist icon to complete its restoration. Such stewardship of a single building, by one firm over a seven-decade period, is a rarity in the architectural profession. Working closely with the Landmarks Preservation Commission, which made Lever House the city’s first modernist Landmark in 1982, SOM is in the process of restoring the primary public and private spaces to their original glory, and providing key infrastructural upgrades that will significantly improve the building’s energy performance. This renovation and restoration will revitalize Lever House and make it once again Park Avenue’s premier boutique office building.

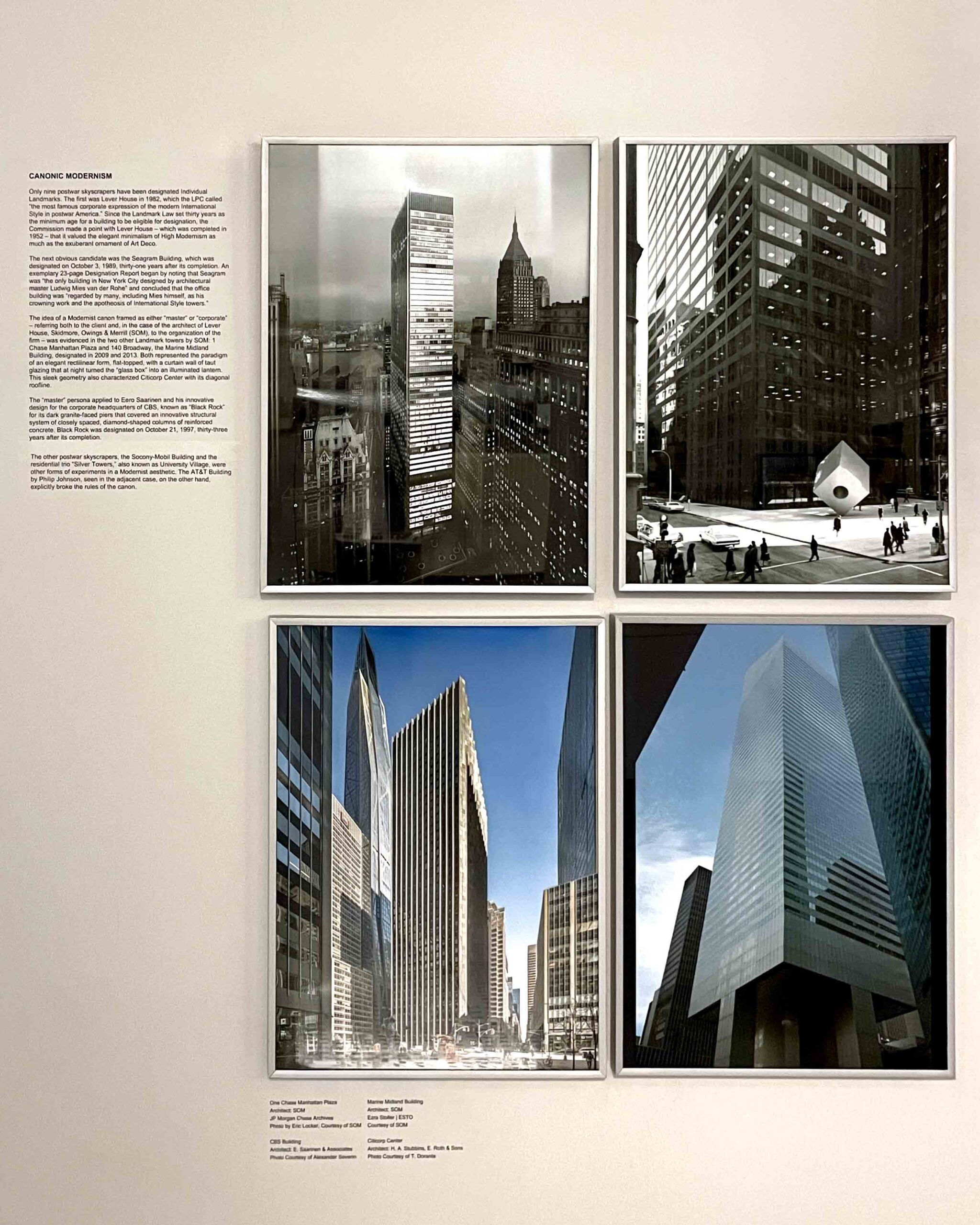

One Chase Manhattan Plaza

Architect: SOM

JP Morgan Chase Archives

Photo by Eric Locker, Courtesy of SOM

Marine Midland Building

Architect: SOM

Ezra Stoller | ESTO

Courtesy of SOM

CBS Building

Architect: E. Saarinen & Associates

Photo Courtesy of Alexander Severin

Citicorp Center

Architect: H. A. Stubbins, E. Roth & Sons

Photo Courtesy of T. Dorante

MODERNIST ICONS

Only nine postwar skyscrapers have been designated Individual Landmarks. The first was Lever House in 1982, which the LPC called “the most famous corporate expression of the modern International Style in postwar America.” Since the Landmarks Law set thirty years as the minimum age for a building to be eligible for designation, the Commission made a point with Lever House – which was completed in 1952 – that it valued the elegant minimalism of High Modernism as much as the exuberant ornament of Art Deco.

The next obvious candidate was the Seagram Building, which was designated on October 3, 1989, thirty-one years after its completion. An exemplary 23-page Designation Report began by noting that Seagram was “the only building in New York City designed by architectural master Ludwig Mies van der Rohe” and concluded that the office building was “regarded by many, including Mies himself, as his crowning work and the apotheosis of International Style towers.”

The idea of a Modernist canon framed as either “master” or “corporate” – referring both to the client and, in the case of the architect of Lever House, Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM), to the organization of the firm – was evidenced in the two other Landmarked towers by SOM: 1 Chase Manhattan Plaza and 140 Broadway, the Marine Midland Building, designated in 2009 and 2013. Both represented the paradigm of an elegant rectilinear form, flat-topped, with a curtain wall of taut glazing that at night turned the “glass box” into an illuminated lantern. This sleek geometry also characterized Citicorp Center with its diagonal roofline.

The “master” persona applied to Eero Saarinen and his innovative design for the corporate headquarters of CBS, known as “Black Rock” for its dark granite-faced piers that covered an innovative structural system of closely spaced, diamond-shaped columns of reinforced concrete. Black Rock was designated on October 21, 1997, thirty-three years after its completion.

The other postwar skyscrapers, the Socony-Mobil Building and the residential trio “Silver Towers,” also known as University Village, were other forms of experiments in a Modernist aesthetic. The AT&T Building by Philip Johnson, seen in the adjacent case, on the other hand, explicitly broke the rules of the canon.

Irving Trust/Bank of NY, 1929-1931

1 Wall St.

Architect: Ralph Walker

Designation: March 6, 2001

ONE WALL STREET

One Wall Street has been a prestige address since the early-20th century when a very slender 18-story office building was erected on a tiny lot on Broadway across from Trinity Church and one block from the New York Stock Exchange. In 1928, the powerful interests of the Irving Trust Bank purchased One Wall Street and neighboring buildings to assemble a site that covered the full block to New Street and stretched along Broadway – which meant the office building could stand free, with windows on all sides. The design by Ralph Walker was the architect's most elegant essay among his four LPC-designated Art Deco towers. The expensive limestone façade was sculpted in a curtain-like undulation that softened the play of light and shadow. The 50-story skyscraper began construction in 1929 and was completed in 1931, well after the stock market crash. It became a Landmark on March 6, 2001, as one of the last of the campaign of Financial District designations under Chair Jennifer Raab.

Developer Harry Macklowe purchased One Wall Street in May 2014 from BNY Mellon, initially with plans to convert it to hotel and residential use. He worked with several architects on plans that shifted the mix of units and added floors above the 1961 annex section on Broadway, but left the original tower unchanged. The firm of Robert A.M. Stern developed the new project and took it successfully through the Landmarks review in early 2016 in plans that focused exclusively on condos. To create the 566 apartments and to modernize the building’s elevators and mechanical systems, Macklowe decided on a complete gut rehab of both buildings, so only the exterior walls and the interior skeleton and floors remained. RAMSA later withdrew from the commission and SLCE is credited as the Architect of Record.

This elaborate presentation model was created by Kennedy Fabrications. On loan courtesy of Macklowe Properties.

Bankers Trust Company Building Annex, west end of main banking hall, February 28, 1933 (left) and construction of the main banking hall, March 14, 1933 (right). Collection of The Skyscraper Museum.

The Big Buildings exhibition in the Bankers Trust grand hall in 1998.

BANKERS TRUST

It is often said that the only constant in New York is change. The Bankers Trust Building at 14 Wall Street, designated in 1997, is a site and building that intensified the dynamic of growth and change that so often applies in skyscraper development. The 41-story tower is the second skyscraper to rise on the prestigious site at the corner of Wall Street, Broad, and Nassau Street, anchoring the "corner of capital" of the historic Financial District. It replaced the 22-story Gillender Building, erected in 1897 and shown at the far left of the case display in a photo from the Museum's archive just before demolition began in 1910.

The Bankers Trust Tower, which covered more than four times the area, was the tallest banking building in the world when it opened in 1912. The land on which it rose was, at the time, the most expensive conveyance, per square foot, ever recorded. Twenty years later the wealthy bank bought and demolished more old buildings and expanded with an annex designed by Shreve, Lamb & Harmon, architects of the Empire State Building, tripling the office area. The architects also enlarged and modernized the original classical with a monumental Art Deco banking hall, shown in construction photographs from our collection (left).

In 1998-1999, The Skyscraper Museum occupied the Bankers Trust grand hall, which had been made vacant due to a bank merger and a real estate recession, and mounted two exhibitions, shown in the color snapshots to the left. Today the great space, which was not protected as an Interior Landmark, has been destroyed in a conversion to a commercial gym. Other Financial District Landmarks have managed to preserve their historic features even without designation by the LPC, but nothing prevents an owner from altering or destroying interiors.

AT&T Building, 1978-1984

500 Madison Ave.

Architect: Philip Johnson & John Burgee

Designation: July 31, 2018

AT&T BUILDING

The AT&T Building: Philip Johnson and The Postmodern Skyscraper

Designed in 1978 and completed in 1984, the AT&T Building reasserted the idea of “Sky Mark” that had been a defining characteristic of towers of the Twenties, but had disappeared entirely in the postwar era of International Style Modernism. Ironically, it was Philip Johnson – who had championed the minimalist and functionalist aesthetics of the European avant garde as a curator at MoMA in the 1930s and had collaborated with Mies van der Rohe on the Seagram Building in the 1950s – who was architect for a new headquarters for AT&T, then the largest company in the world.

Influential without equal in American architectural culture, Johnson was both celebrated and controversial, and he used the commission to make a statement and generate news. The unveiling of the design appeared on the front page of The New York Times in 1978 and attracted immense critical attention and debate: it was dubbed “the first Postmodern skyscraper." With its granite-not-glass façade and split-pediment “Chippendale” roofline, Johnson’s AT&T overturned – or at least undermined for a decade – the aesthetics of Modernism he had helped establish as orthodoxy.

By 1984 when the building opened to fanfare, government anti-trust actions were breaking up AT&T. In 1991, the tower was leased to Sony, who occupied and then purchased the building. Some alterations to the original Madison Avenue arcades and to the mid-block plaza were made during that time and have been redesigned in the LPC-approved redesigns by Snøhetta.

This period model of the AT&T Headquarters Building is on loan from the Olayan Group. Johnson holds one of these models in the photos in the brochure at the rear of this case and on the cover of Time.

The Snøhetta Plaza at 550 Madison

On July 31, 2018, the AT&T Building became the city’s youngest skyscraper Landmark. A new owner, the Olayan Group, has undertaken a major modernization and has worked with a team of designers, inside and out, to reinvent the building, now named for its address, 550 Madison. The firm Snøhetta was the architect for adjustments to the façade and the redesigned POPS (Privately-Owned Public Space) plaza, which can be seen in their model. Both the LPC and the Department of City Planning oversaw the redesign of the greatly enlarged and canopied, through-block public plaza that includes a varied landscape of trees and shrubs, a sculptural waterfall, seating areas, and facilities.

Architects, Celebrity, and History

While the AT&T Building was controversial from the start – and remains no less so today – its historical status as the most significant skyscraper in New York since the Seagram Building (as Johnson intended!) seems beyond debate.

Philip Johnson understood the power of celebrity and media, as his pose on the cover of Time's January 28, 1979 issue attests. The feature article by critic Robert Hughes named him “the leading American architect of his generation.”

Although its ultimate designation as an Individual Landmark was certainly assured, in 2018, preservationist champions of Postmodernism lobbied the LPC to accelerate the designation process with letters, social media, and a sidewalk protest that cleverly recalled the famous photos of Philip Johnson, Jane Jacobs, and other activists' attempts in 1963 to save the old Penn Station.