The map of Midtown South from 14th to 34th Streets, with few Individual Skyscraper Landmarks, is blanketed by large Historic Districts, notably Ladies' Mile and Madison Square North. Both areas are characterized by a mix of sizes and styles of commercial buildings, many high-rises, that, for the most part, span the 1880s through the 1910s. As Historic Districts, the designated areas possess a “distinct sense of place” that the LPC regulates, requiring any significant changes to buildings to be reviewed and approved as "appropriate."

HISTORIC DISTRICTS

Historic Districts were part of the original 1965 Landmarks Law. Most designated Historic Districts are residential, not commercial, and the impetus for their protection often comes from activist residents and preservation advocates rather than from the LPC. An exception to the emphasis on residential is the Ladies’ Mile Historic District, encompassing 28 blocks north of Union Square along Broadway and west to Sixth Avenue, where in the 19th and early-20th century fashionable retail and commercial high-rises and light-manufacturing lofts on the cross streets flourished. Nearby, Madison Square North Historic District protects a similar mix of mostly early-20th century buildings.

The designation of Historic Districts tends to preserve property values, which is one reason they are usually welcomed by owners of residential buildings. But Historic Districts also come with regulation that requires changes to buildings within the boundaries be approved by LPC staff or, if substantial, at a public hearing for a Certificate of Appropriateness. This process adds time and expense to projects, which is why many owners of commercial properties oppose designation.

LOWER MANHATTAN HISTORIC DISTRICT?

The southern tip of Manhattan – home to the city’s original colonial settlement, booming 19th century world port, and epicenter of banking and finance – is one of the most richly historic areas in America. It possesses a distinctive and coherent “sense of place,” but it is not a designated Historic District.

Lower Manhattan remained almost exclusively a business district until the mid-1990s, when City initiatives and incentives began to encourage the conversion of older office buildings to residential use. Historic preservation and Landmark designation played an important role in these policies. In addition, a new emphasis on cultural tourism celebrated the historical, cultural, and aesthetic character of the extraordinary architecture of the historic core. For more detail on Downtown Landmarks see DOWNTOWN LANDMARKS.

INTERIORS SHOWN IN PROJECTION

Empire State Building

Barclay-Vesey Building

Western Union Building

Long Distance Building of AT&T

Woolworth Building

Cities Service Building

RCA Building

Fred F. French Building

Chrysler Building

INTERIOR LANDMARKS

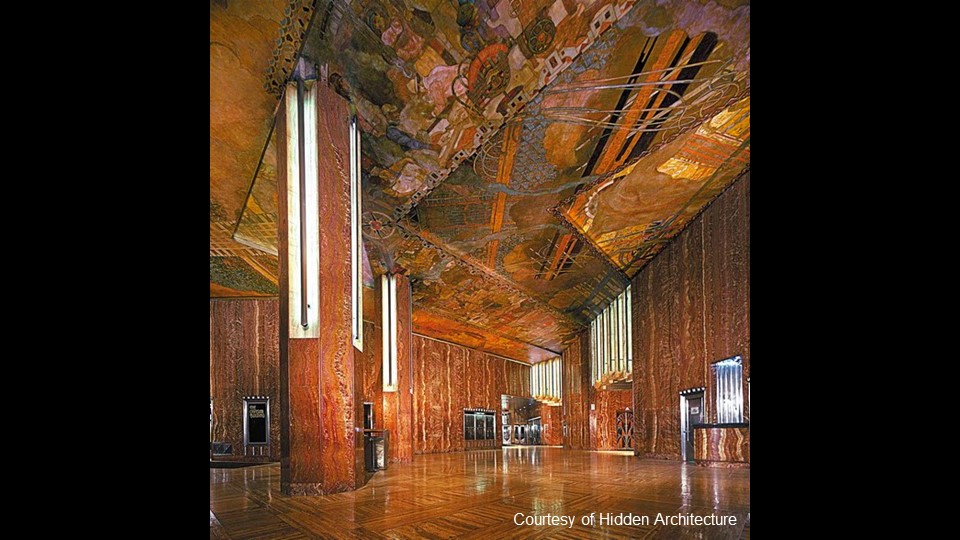

In 1973, Mayor John Lindsay signed legislation that established two new types of Landmark designations: Interior and Scenic. To be eligible to become an Interior Landmark, a building must be “customarily open or accessible to the public,” which means that the lobbies of skyscrapers usually qualify. After the 1978 Supreme Court decision that upheld the constitutionality of the Landmarks Law, there was a spate of designations of iconic Midtown skyscrapers. The Chrysler Building in 1978 and the Empire State Building in 1981 were the first two skyscrapers to have their lobbies designated as Interior Landmarks. The Woolworth Building followed in 1983.

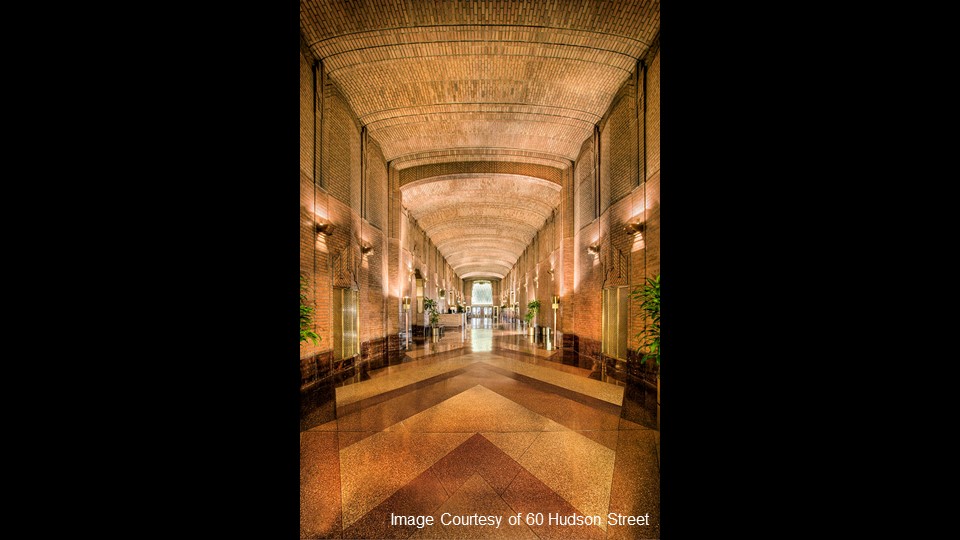

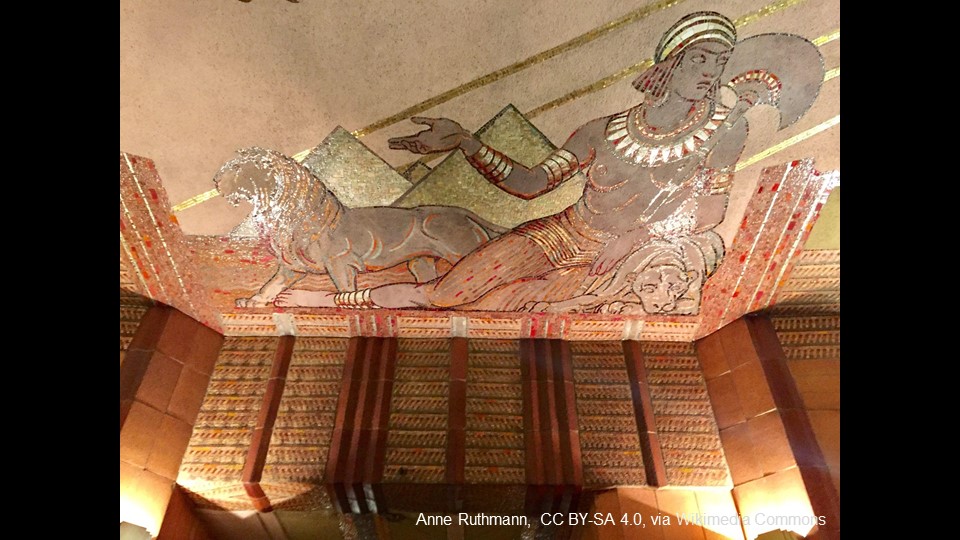

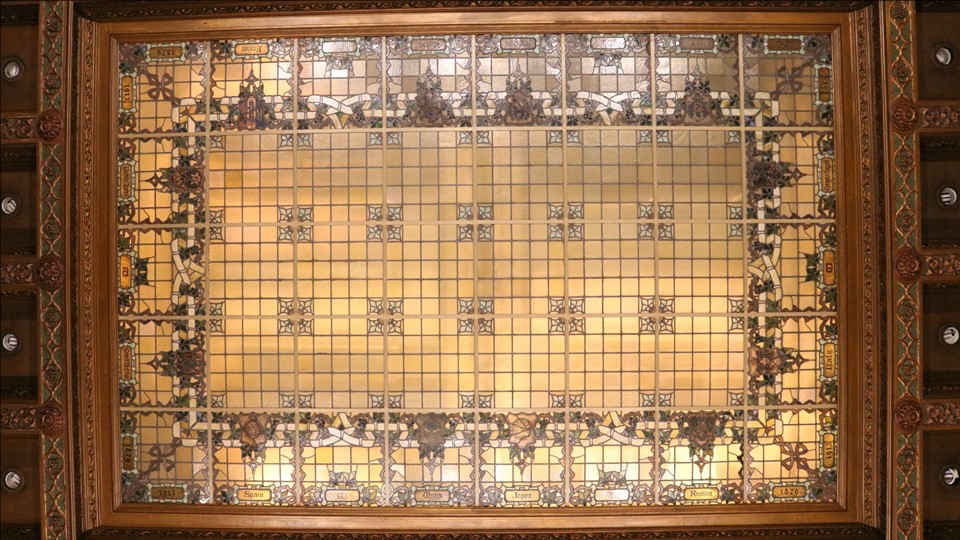

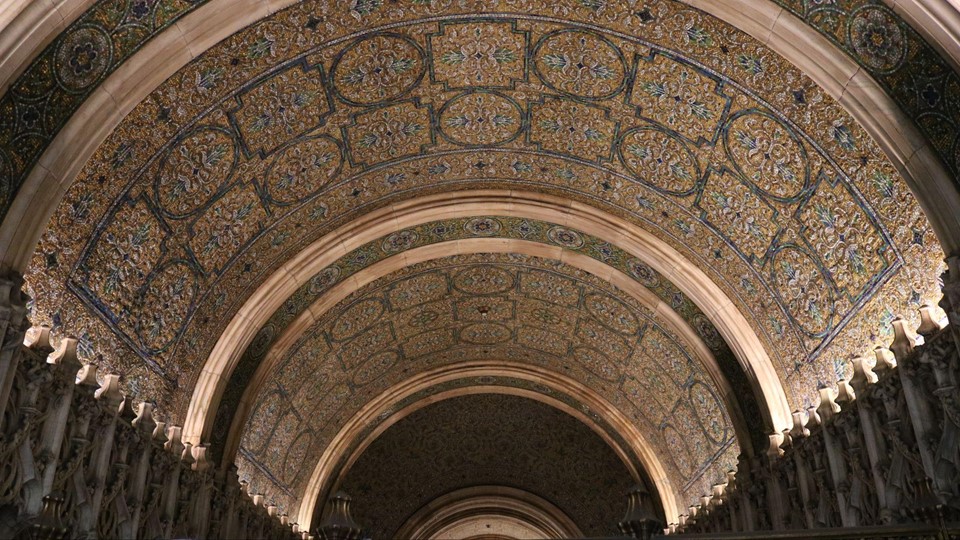

The images projected on this wall offer views of some of the city's most lavish skyscraper lobbies, all Interior Landmarks. This means that any restoration or updates to the space or finishes must be reviewed and approved by the LPC.

WOOLWORTH BUILDING, LOBBY

The Woolworth Building's opulent lobby was designated as both an Interior Landmark and Individual Landmark on April 12, 1983. The lobby had a main entrance on Broadway and side entrances from Barclay Street and Park Place that emphasized a cathedral-like crossing. Behind the elevator banks was an arcade of shops and a grand staircase that led to the banking hall of the Irving National Bank. The main lobby had round-arched vaults and colorful mosaics of blue, green, and gold, inspired more by Early Christian or Byzantine models than by Gothic architecture. Woolworth's promotional literature called the mosaics "a flood of dazzling jewels glittering in the sunlight…a riot of harmonies colors, all spread out in a golden setting, and arranged in exquisite design" –but the lobby is, in fact, windowless, and incandescent up-lighting increased the glittering effect.

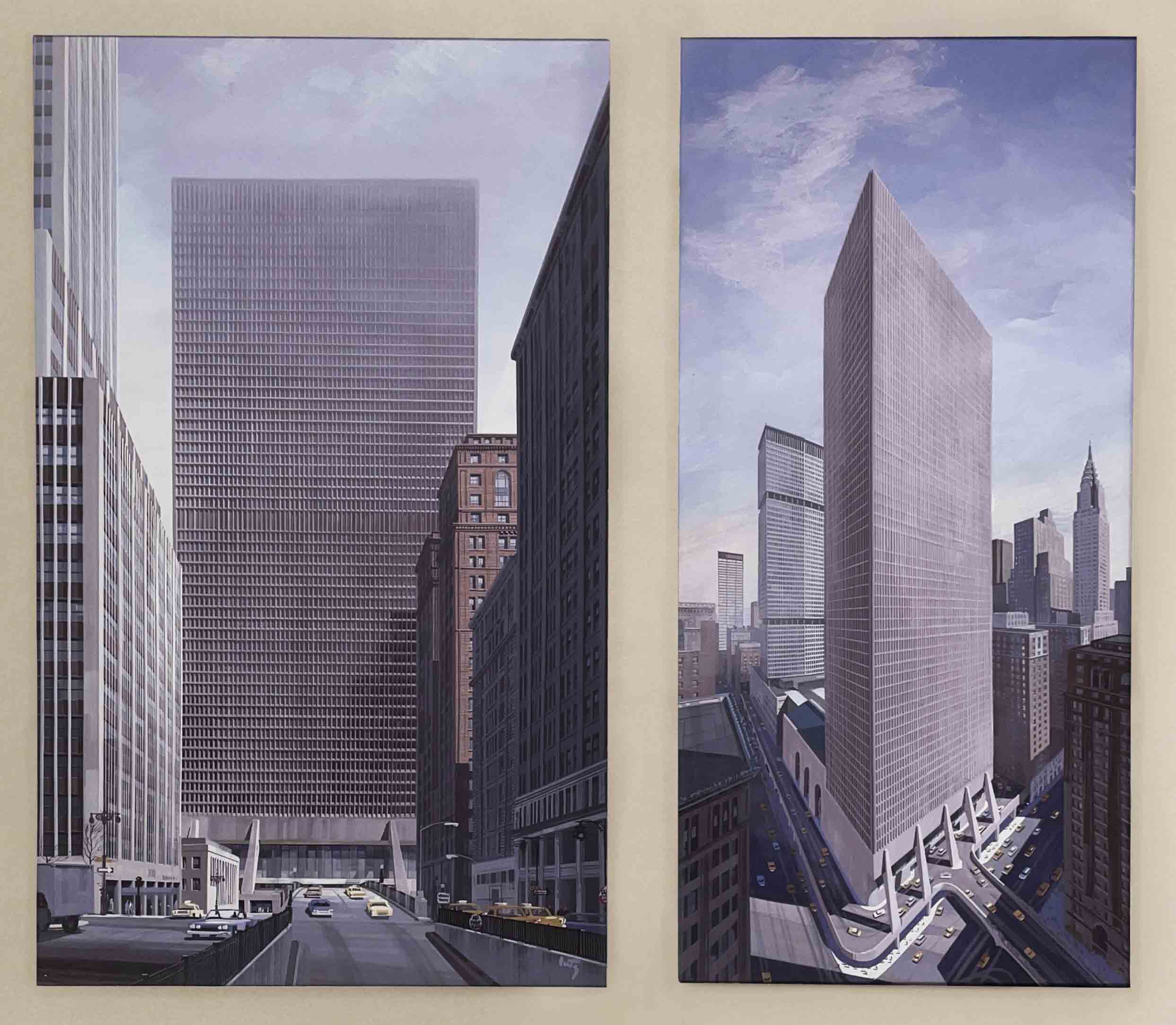

LEFT:

Grand Central Tower, Color Perspective Rendering

Breuer 2A, view from center of Park Ave., 1967-1969 (MC-124_005)

The second version of Breuer’s proposal would destroy the terminal’s façade and sit on tilted supports.

RIGHT:

Grand Central Tower, Color Perspective Rendering

Breuer 2A, view from southwest corner, 1967-1969 (MC-124_004)

This view of the proposal’s second version more clearly illustrates the tilted supports. The Pan Am (now MetLife) Building can be seen in the background, blocked by the new tower from Park Ave. The Chrysler Building is on the right.

Marcel Breuer Papers, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries

THE IMPORTANCE OF GRAND CENTRAL TERMINAL AND THE ABSENCE OF A SKYSCRAPER

Grand Central Terminal was designated an Individual Landmark on August 2, 1967, which meant only the exterior of the building was protected. The Main Concourse received a separate designation on September 23, 1980, six years after Interior Landmarks and Scenic Landmarks were added as categories.

In the early years of the Landmarks Law the Commission worried about court challenges and was especially anxious about the litigious nature of the real estate industry. In 1967, after the Commission voted down a series of proposals by the architect Marcel Breuer to add a massive skyscraper above the facade and the concourse of Grand Central Terminal (shown on the adjacent wall), the Penn Central Railroad sued the City on constitutional grounds of a "taking," and won. The City appealed, but the legal limbo – which lasted for 12 years, until The Supreme Court upheld the Landmarks Law on June 26, 1978. During this time there was an unspoken moratorium on designating skyscrapers. None were proposed from 1969 to 1978, except for the American Radiator Building in 1974.

In 2015, the preservationist and historian Andrew S. Dolkart gave a lecture at the Museum that described the early history of the slow LPC designation of skyscrapers and discussed details of the Breuer design. An 18-minute excerpt of his lecture is presented on this screen.

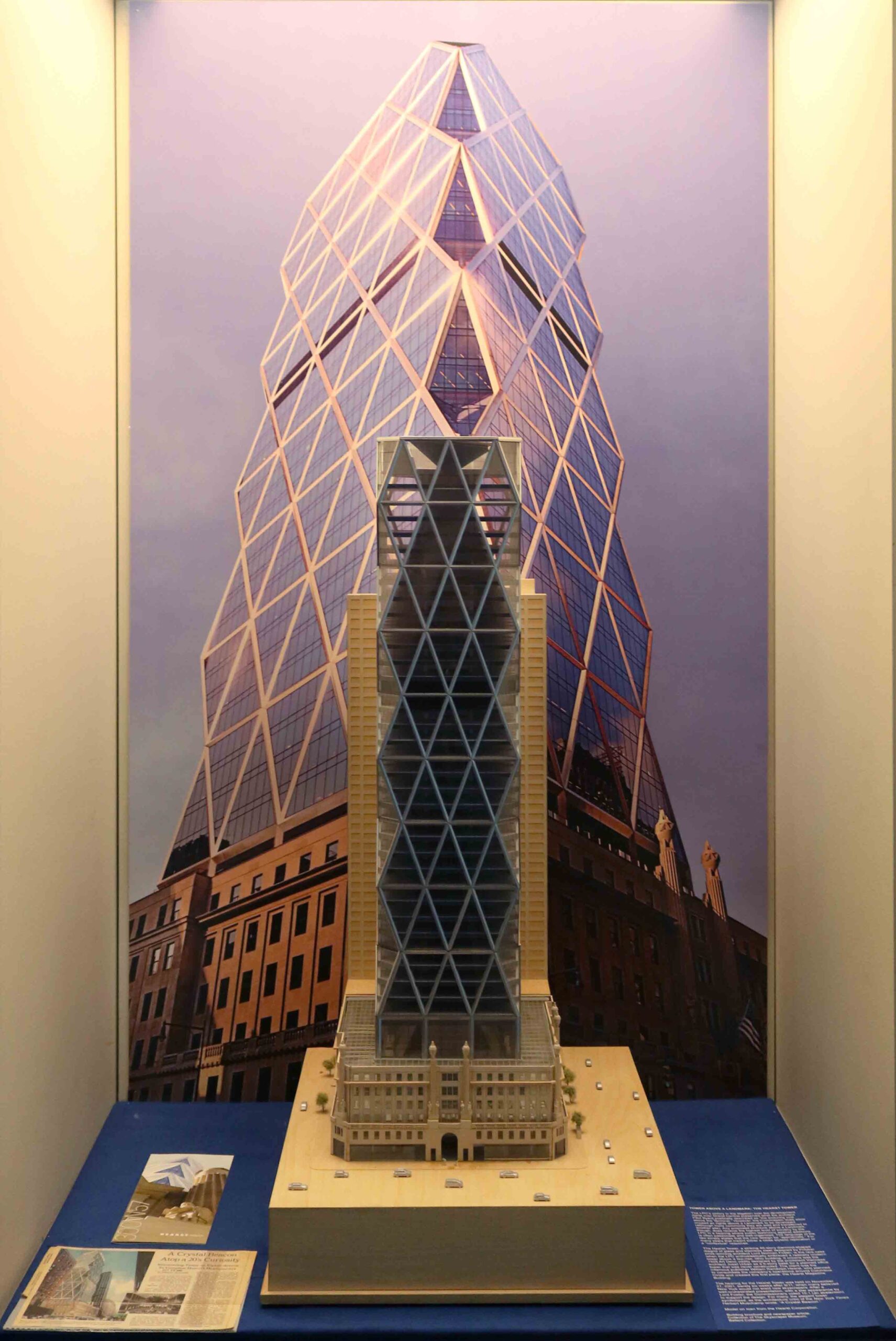

TOWER ABOVE A LANDMARK: THE HEARST TOWER

The LPC’s victory in the litigation over the development rights over Grand Central preserved what the architect Paul Byard poetically described as “the enduring void above the Terminal.” However, the Commission does allow unused air rights above a Landmark to be developed (although more commonly they are sold and transferred to another site). Any proposed structure above a Landmark, though, does receive the highest level of scrutiny by the LPC in a hearing where public testimony against additions is often passionate and well-organized. The language of the law simply states that the new design be “appropriate.” For many years that meant either a close stylistic replication or a “contextual” response.

The Hearst Tower, a striking 46-story diamond-shaped diagrid of glass and stainless steel designed by Pritzker Prize-winning architect Lord Norman Foster, is the rare case when the LPC enthusiastically embraced a radically modern tower above a low-rise, lithic building. It crowns was the 1928 Art Deco oddity designed by the prominent Viennese architect Josef Urban as a 6-story base for a planned office tower that was never constructed. The client was the infamous publisher William Randolph Hearst, who planned to consolidate the company’s operations around Columbus Circle and created this first piece, the Hearst Magazine Building.

The hearing for the Hearst Tower was held on November 27, 2001, barely six weeks after 9/11, when many believed New York would not erect new skyscrapers. After a well-orchestrated presentation, with a star appearance by Lord Foster, the Commissioners voted 10:1 (an abstention) to support the design. For many, the elegant tower symbolized, as the architecture critic of The New York Times Herbert Muschamp wrote, “A Crystal Beacon.”

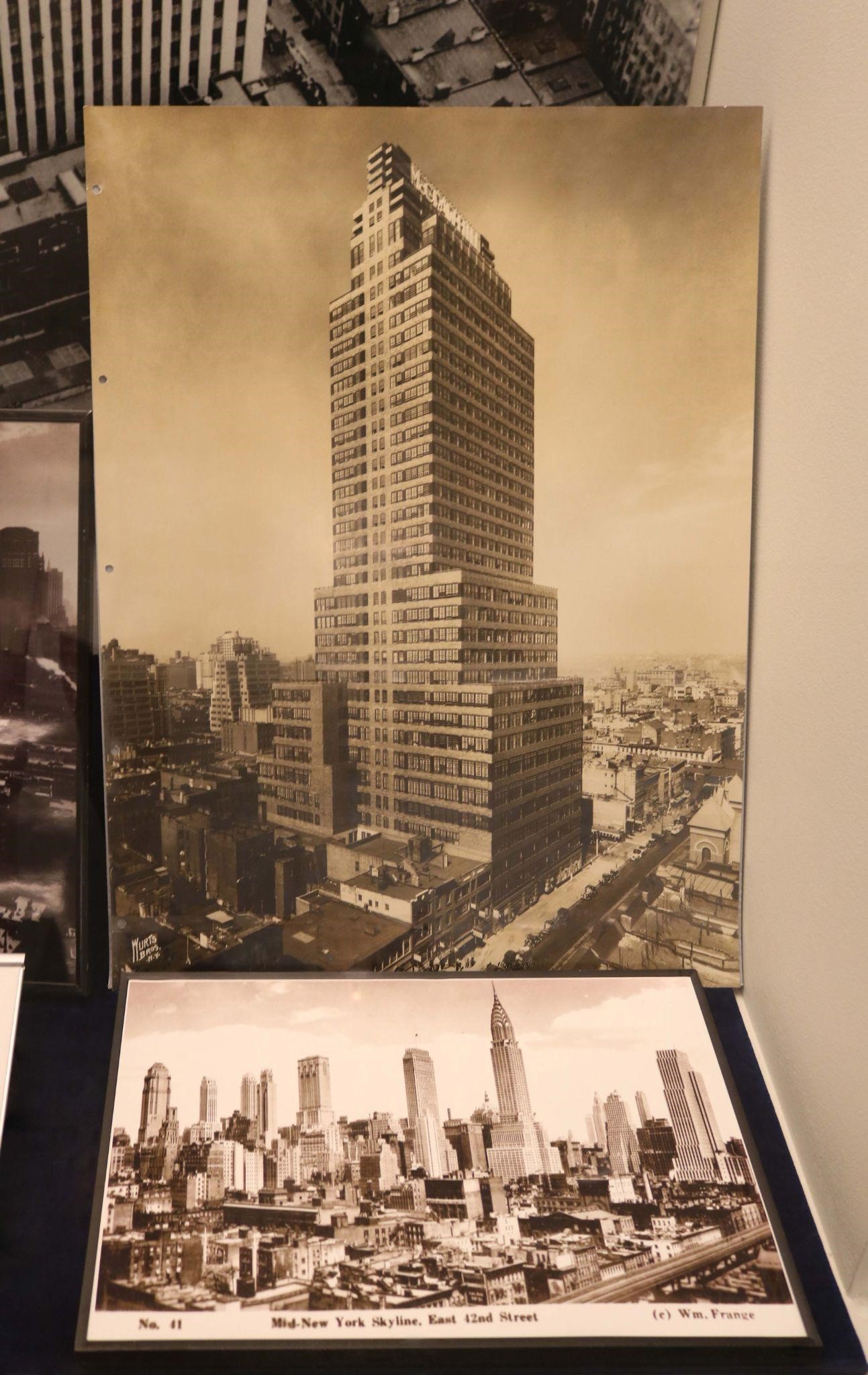

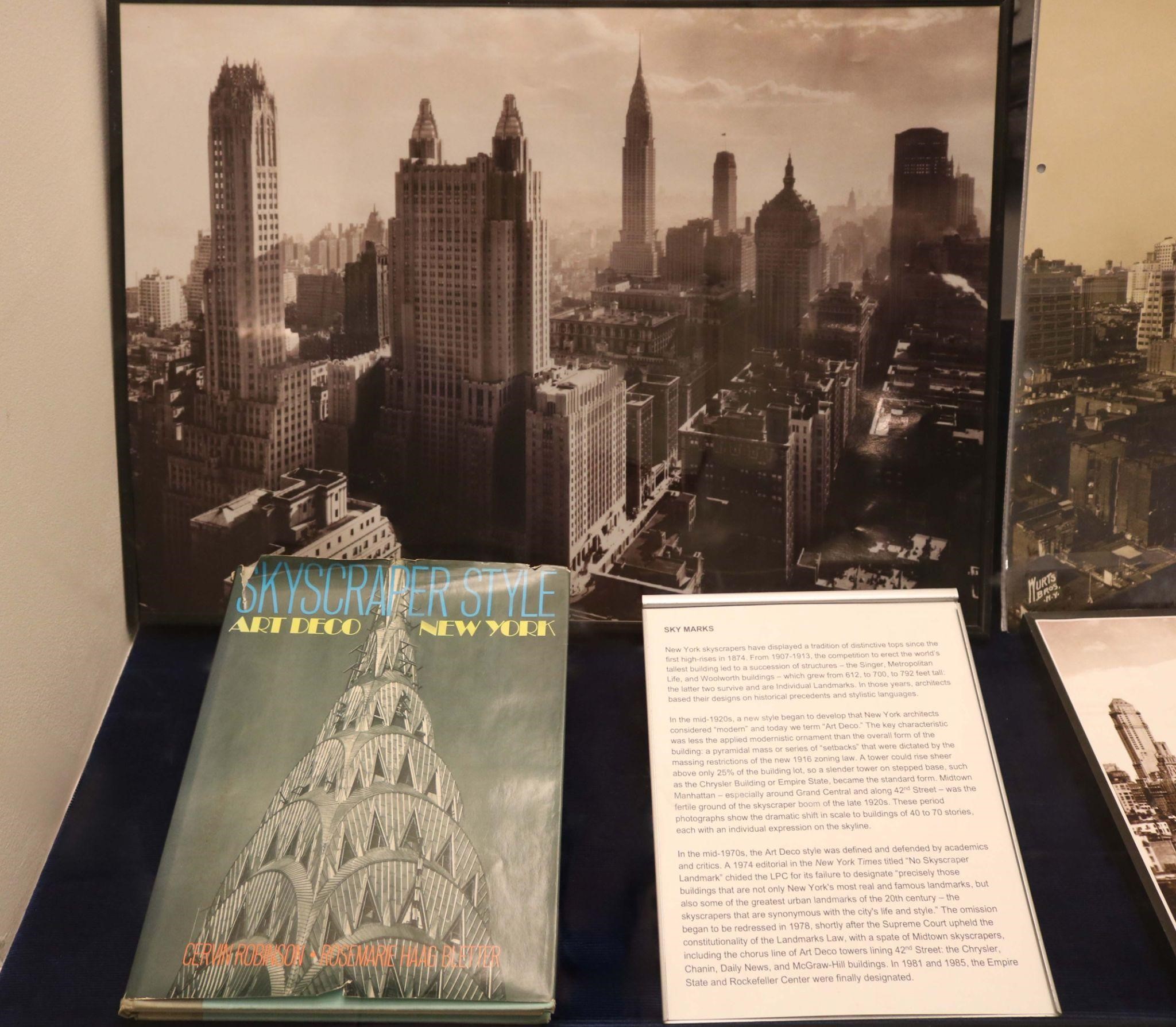

SKY MARKS

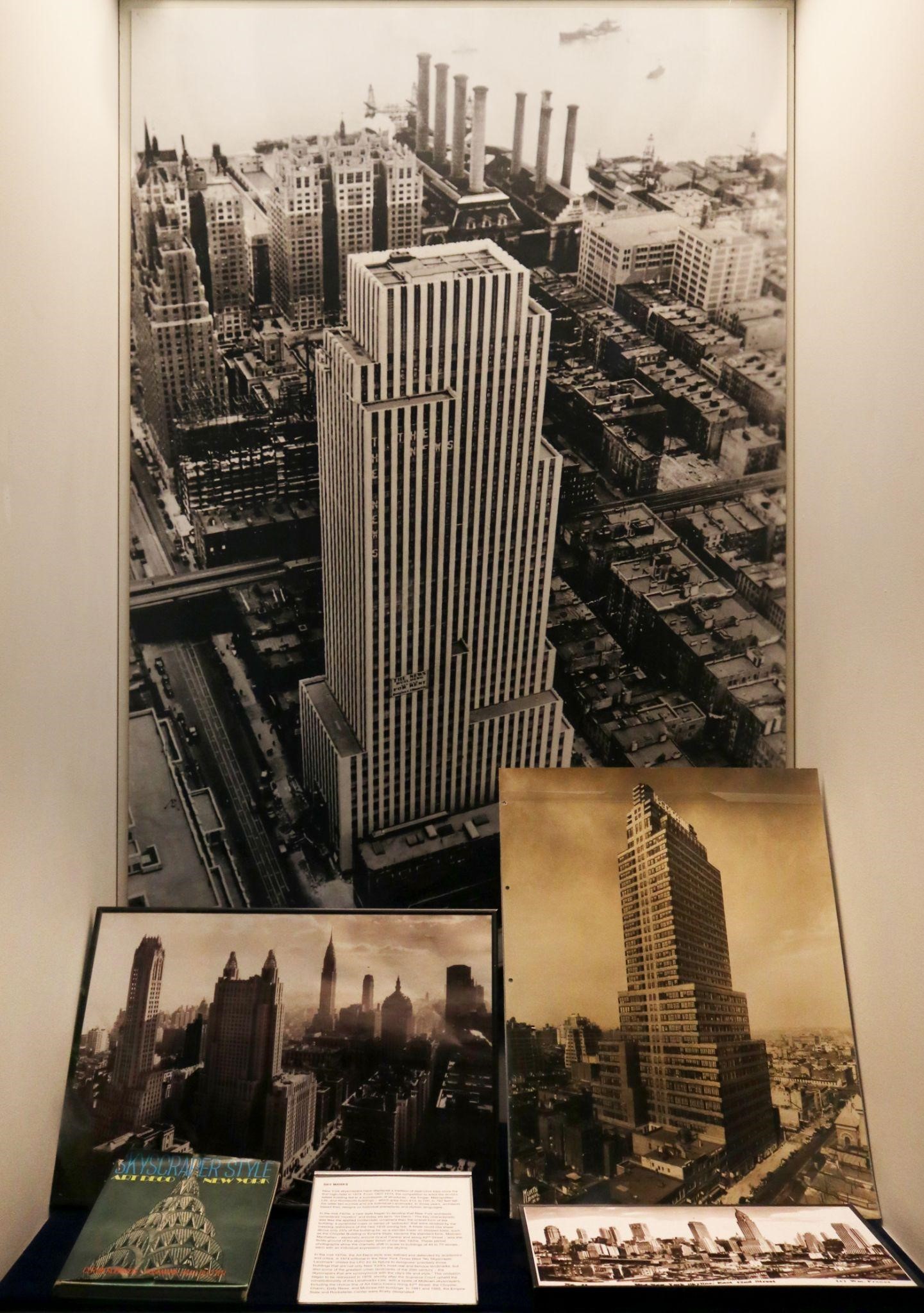

New York skyscrapers have displayed a tradition of distinctive tops since the first high-rises in 1874. From 1907-1913, the competition to erect the world’s tallest building led to a succession of structures – the Singer, Metropolitan Life, and Woolworth buildings – which grew from 612, to 700, to 792 feet tall: the latter two survive and are Individual Landmarks. In those years, architects based their designs on historical precedents and stylistic languages.

In the mid-1920s, a new style began to develop that New York architects considered “modern” and today we term “Art Deco.” The key characteristic was less the applied modernistic ornament than the overall form of the building: a pyramidal mass or series of “setbacks” that were dictated by the massing restrictions of the new 1916 zoning law. A tower could rise sheer above only 25% of the building lot, so a slender tower on stepped base, such as the Chrysler Building or Empire State Building, became the standard form. Midtown Manhattan – especially around Grand Central and along 42nd Street – was the fertile ground of the skyscraper boom of the late 1920s. These period photographs show the dramatic shift in scale to buildings of 40 to 70 stories, each with an individual expression on the skyline.

In the mid-1970s, the Art Deco style was defined and defended by academics and critics. A 1974 editorial in The New York Times titled “No Skyscraper Landmark” chided the LPC for its failure to designate “precisely those buildings that are not only New York's most real and famous landmarks, but also some of the greatest urban landmarks of the 20th century – the skyscrapers that are synonymous with the city's life and style.” The omission began to be redressed in 1978, shortly after the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the Landmarks Law, with a spate of Midtown skyscrapers, including the chorus line of Art Deco towers lining 42nd Street: the Chrysler, Chanin, Daily News, and McGraw-Hill buildings. In 1981 and 1985, the Empire State Building and Rockefeller Center were finally designated.

LOWER MANHATTAN LANDMARKS

A signal achievement of government in Lower Manhattan in the second half of the 1990s was the addition of twenty-four new Individual Landmarks and one new Historic District, Stone Street. Twenty of these were skyscrapers of the 1910s to 1930s, mostly in the Financial District. Owners in the area had long resisted LPC regulation, objecting to control over their property and to what might be even more valuable, the land the structures occupied.

In the real estate slump of the Nineties, though, and under the Chairmanship of Jennifer Raab from 1994 to 2001, arguments for Landmark designation had a new logic. The City began to put in place policies that incentivized the restoration and interior upgrades of older office buildings, as well as their conversion to residential use. Buildings that were designated Landmarks or were added to the National Register were further eligible for federal historic preservation tax credits and other city tax breaks.

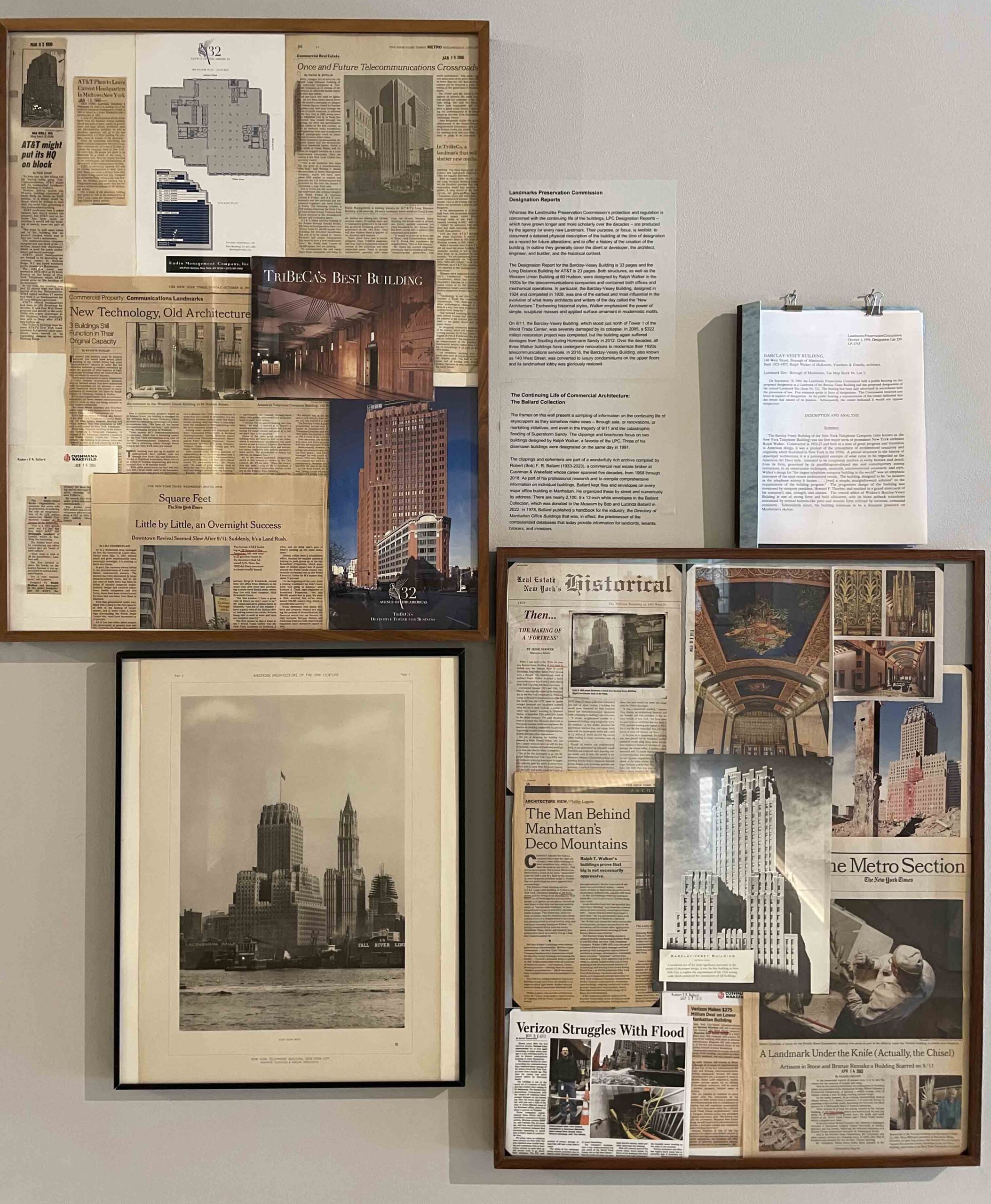

BALLARD COLLECTIONS

The Continuing Life of Commercial Architecture:

The Ballard Collection

The frames on this wall present a sampling of information on the continuing life of skyscrapers as they somehow make news – through sale, or renovations, or marketing initiatives, and even in the tragedy of 9/11 and the catastrophic flooding of Superstorm Sandy. The clippings and brochures focus on two buildings designed by Ralph Walker, a favorite of the LPC. Three of his downtown buildings were designated on the same day in 1991.

The clippings and ephemera are part of a wonderfully rich archive compiled by Robert (Bob) F. R. Ballard (1933-2023), a commercial real estate broker at Cushman & Wakefield whose career spanned five decades, from 1968 through 2018. As part of his professional research and to compile comprehensive information on individual buildings, Ballard kept files and envelopes on every major office building in Manhattan. He organized these by street and numerically by address. There are nearly 2,100, 9 x 12-inch white envelopes in the Ballard Collection, which was donated to the Museum by Bob and Lucinda Ballard in 2022. In 1978, Ballard published a handbook for the industry, the Directory of Manhattan Office Buildings that was, in effect, the predecessor of the computerized databases that today provide information for landlords, tenants, brokers, and investors.

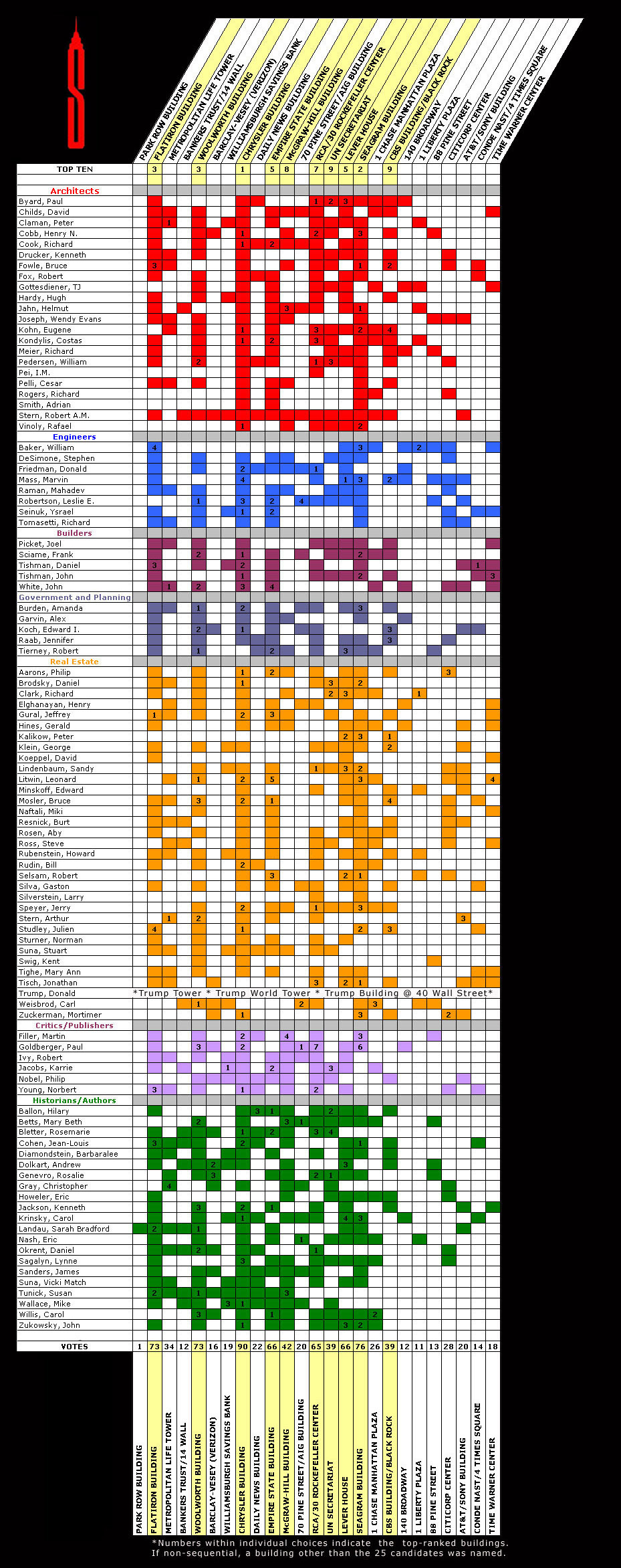

FAVORITES

Individual Landmark designation is not meant to be a popularity contest: it’s a judgment by professionals who represent government and who evaluate the architectural, historical, or cultural importance of a building that should be protected for future generations.

Back in 2005, The Skyscraper Museum conceived a light-hearted exhibition around a survey of 100 knowledgeable New Yorkers and building industry professionals, including architects, engineers, developers, brokers, builders, historians, and critics. We selected the 25 buildings that represented a spectrum of significant skyscrapers, from the Park Row Building to the Time Warner Center and asked people to rank their favorites.

The results were mounted in the exhibition FAVORITES for which we printed this poster. Number 1 by a landslide was the Chrysler Building, making the list of 9 out of 10 participants, with 18 naming it their absolute Favorite. The Seagram Building took second place with 76 votes, while the Woolworth and Flatiron buildings tied with 73. the Empire State Building and Lever House ran a dead heat for fifth, followed by the RCA Building at 30 Rockefeller Center. Trailing these stars by more than 20 votes were the McGraw-Hill Building, the CBS Building / Black Rock, and the UN Secretariat. What’s your Favorite?