The Museum's October 2017 through June 2018 exhibition MILLENNIUM: Lower Manhattan in the 1990s was documented in an online version that was hard-coded and buggy. All the content of that site is transferred here on a new platform, but without changing tenses from present to past.

The last decade of the 20th century in New York City was not a simple time. The end of a millennium – a thousand-year marker – and the beginning of the 2000s prompted both anxiety and optimism, posing questions about what to retain from the past and how to move into the future. No place in the mid-1990s was more conflicted about these prospects or more ripe for reinvention than lower Manhattan – especially the historic Financial District. Wall Street was losing banks to mergers and relocations. Grand skyscrapers of the 1910s and ‘20s were becoming technologically obsolete and sliding down-market. The lasting effect of the 1987 stock market crash, followed by the savings-and-loan scandals, caused a real estate recession that hit Downtown harder than other districts. Vacancy rates for office buildings topped 28 percent. New thinking and policies were necessary.

Preservation and reinvention were twin themes of the Downtown discussion. Landmarking and converting older office buildings to residential and other uses were strategies of economic development. Celebrating the district’s rich history and creating a culture for tourism was another initiative, led by Heritage Trails New York.

Twenty years ago, the nascent Skyscraper Museum used the real estate recession to find free space for its first pop-up exhibitions in grand vacant banking halls at 44 Wall Street and 14 Wall. MILLENNIUM revisits this recent history of lower Manhattan in the years just before Downtown’s identity was cataclysmically recast as Ground Zero, and a new era truly began.

The only remaining original Heritage Trails marker is on permanent display in the National September 11 Museum. The panel was originally located in Tobin Plaza at the of the Twin Towers and salvaged after the attacks of September 11, 2001.

Installation view.

MIXED MESSAGES OF THE MILLENNIUM

Some historical divisions are artificial and conventional, such as decades and centuries, and some are meaningful and definitive, like prewar and postwar. The countdown to New Year’s Eve 2000, of course, attracted worldwide media attention, ranging from reporting on real fears of a “Y2K” computer apocalypse to futuristic musings from profound to funny, as this sampling of newspapers and magazines suggest.

No one knew then that the defining year of change would begin on September 11, 2001.

STARTING THE SKYSCRAPER MUSEUM

The recession in commercial real estate in the mid-1990s enabled The Skyscraper Museum to get its start. Vacancy rates for office buildings in the historic Financial District were especially high – around 25 to 30 percent – because so many banks and financial services companies had merged or moved out of the area. Low rents did draw new types of tenants, such as architectural and engineering firms, to some in older, landmark-quality towers, but retail space languished. Vacant ground-level space in former flagship banking halls was especially affected because the grand scale of the interiors could attract no suitable tenants.

In this economic climate, the nascent non-profit Skyscraper Museum was able to find space to mount its pop-up exhibitions, which was leased for free, so long as it promised to leave the space on a 30-day notice. The Museum occupied three such vacant banking halls from 1997 through October 2001: 44 Wall Street and 14 WallStreet and 110 Maiden Lane. Photo prints of the four exhibitions at those venues are collaged on this wall, along with graphics created for those shows by Pentagram, with Michael Gericke as the design partner.

The Museum’s inaugural exhibition “DOWNTOWN NEW YORK: The Architecture of Business / The Business of Buildings” opened in April 1997 in donated space at 44Wall Street, at the corner of William Street.

The Museum’s second and third exhibitions were held in the monumental banking hall at 14 Wall Street, a spectacular 1932 Art Deco interior of designed by Shreve, Lamb & Harmon, architects of the Empire State Building, which has since been destroyed in the remodeling for a health club. The 8,000 sq. ft. space of the original Bankers Trust skyscraper headquarters had been left empty in the mid-1990s after a succession of mergers of large banks located in the Financial District, including Bankers Trust, Deutsche Bank, Manufacturers Hanover, Chemical, Chase Manhattan, and JP Morgan, reduced the need for flagship branches.

From October 1998 through September 1999, the Museum presented the exhibition BUILDING THE EMPIRE STATE, which documented the astonishing 11-month construction cycle of New York’s signature skyscraper. In October 1999, it mounted a new show, BIG BUILDINGS, which expanded the popular fixation on the history of New York’s TALLEST buildings with a list of its LARGEST high-rises, as measured by floor area. Graphics from that exhibit are mounted on this wall. When the space at 14-16 Wall Street was rented in December 1999, the Museum moved on to its third temporary location, a 1960s bank branch at 110 Maiden Lane.

By 1999, The Skyscraper Museum enjoyed the promise of its permanent home in Battery Park City and began work on a capital campaign. To remain visible and active as an exhibiting institution, the Museum presented a new show, DESIGN DEVELOPMENT: TIMES SQUARE, featuring architectural models for six then-new Times Square towers. 9/11 closed the gallery, and we shared our space for months with an emergency information center that assisted downtown businesses. From late 2001 to March 2004, the Museum pursued its plans for the new home from office space at 55 Broad Street, donated as at Madien Lane, by Rudin Management.

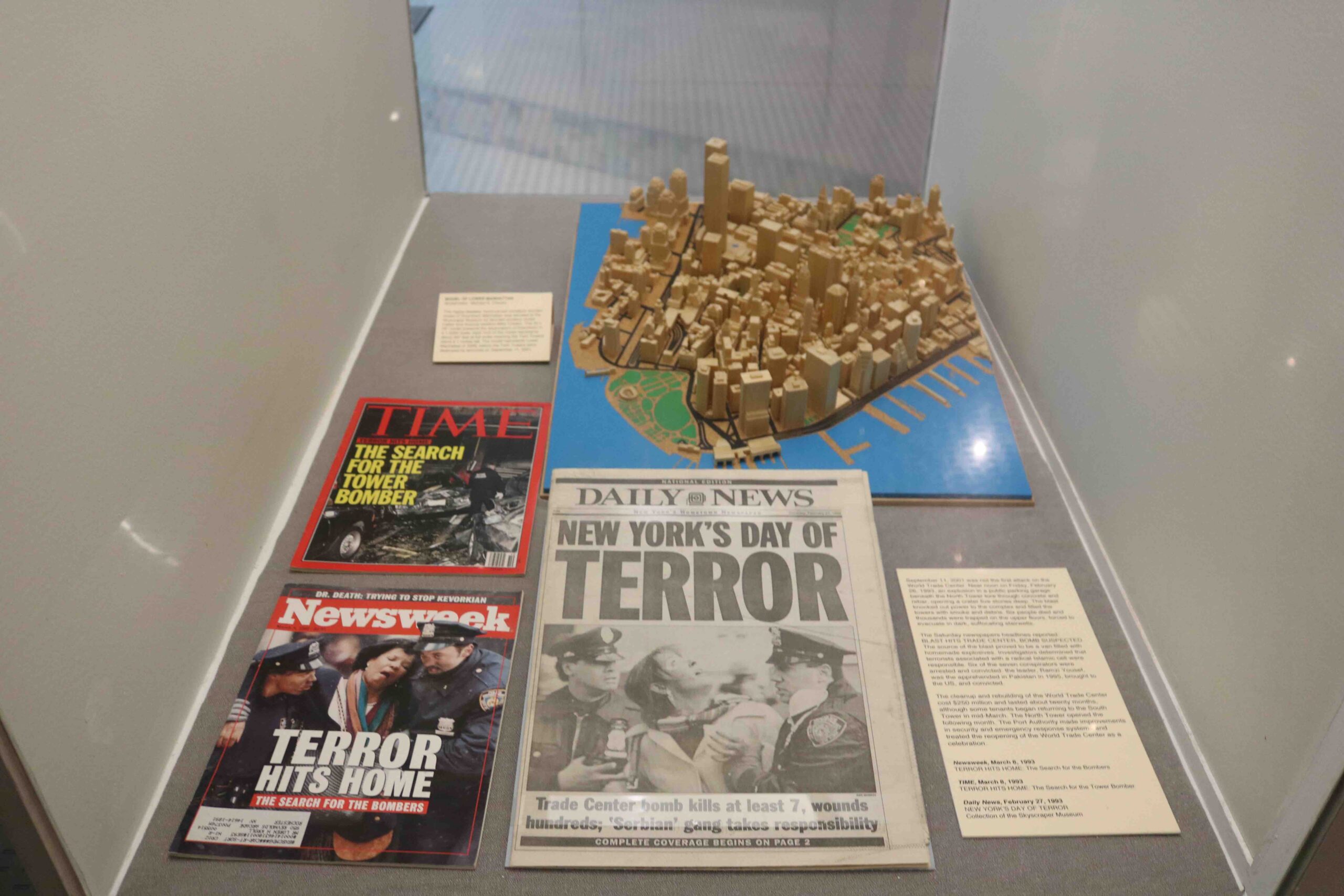

Shown inside the case:

Newsweek, March 8, 1993. TERROR HITS HOME: The Search for the Bombers, TIME, March 8, 1993. TERROR HITS HOME: The Search for the Tower Bomber Daily News, February 27, 1993. NEW YORK’S DAY OF TERROR. Collection of the Skyscraper Museum.

Model of Lower Manhattan created by Modelmaker, Michael G. Chesko.

WORLD TRADE CENTER

September 11, 2001 was not the first attack on the World Trade Center. Near noon on Friday, February 26, 1993, an explosion in a public parking garage beneath the North Tower tore through concrete and rebar, opening a crater five stories deep. The blast knocked out power to the complex and filled the towers with smoke and debris. Six people died and thousands were trapped on the upper floors, forced to evacuate in dark, suffocating stairwells.

The Saturday newspapers headlines reported: BLAST HITS TRADE CENTER, BOMB SUSPECTED. The source of the blast proved to be a van filled with homemade explosives. Investigators determined that terrorists associated with a radical Islamic cell were responsible. Six of the seven conspirators were arrested and convicted: the leader, Ramzi Yousef, was the apprehended in Pakistan in 1995, brought to the US, and convicted.

The cleanup and rebuilding of the World Trade Center cost $250 million and lasted about twenty months, although some tenants began returning to the South Tower in mid-March. The North Tower opened the following month. The Port Authority made improvements in security and emergency response systems and treated the reopening of the World Trade Center as a celebration.

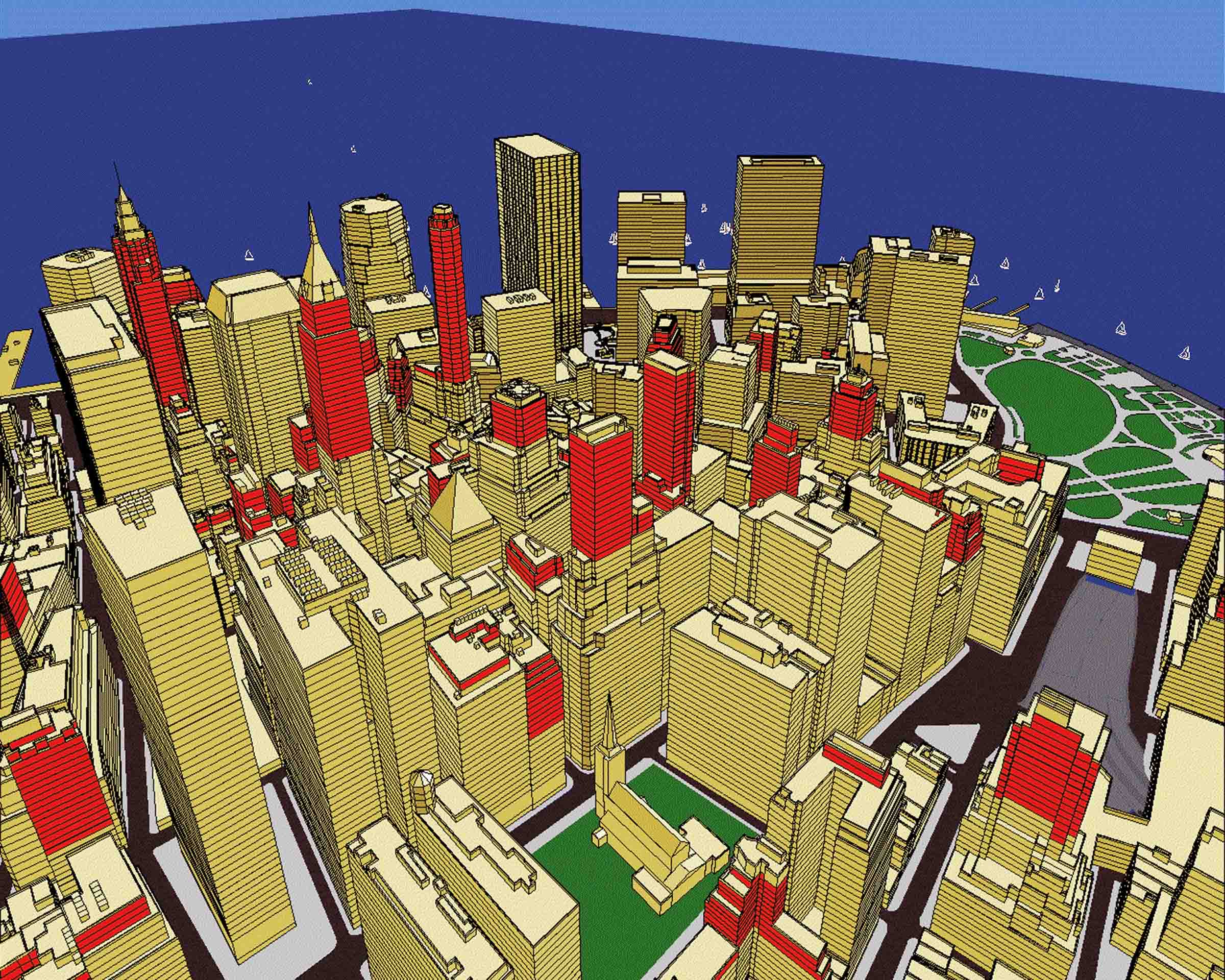

This highly-detailed, hand-carved miniature wooden model of Downtown Manhattan was donated to the Skyscraper Museum by devoted amateur model maker and Arizona resident Mike Chesko. The 35 x 29” model presents the skyscrapers of Downtown in a 1:3200 scale; each inch of the model represents about 267 feet at full scale meaning the Twin Towers stand 5.1 inches tall. The model represents Lower Manhattan in 2000, before the Twin Towers were destroyed by terrorists on September 11, 2001.

HUDSON RIVER WATERFRONT

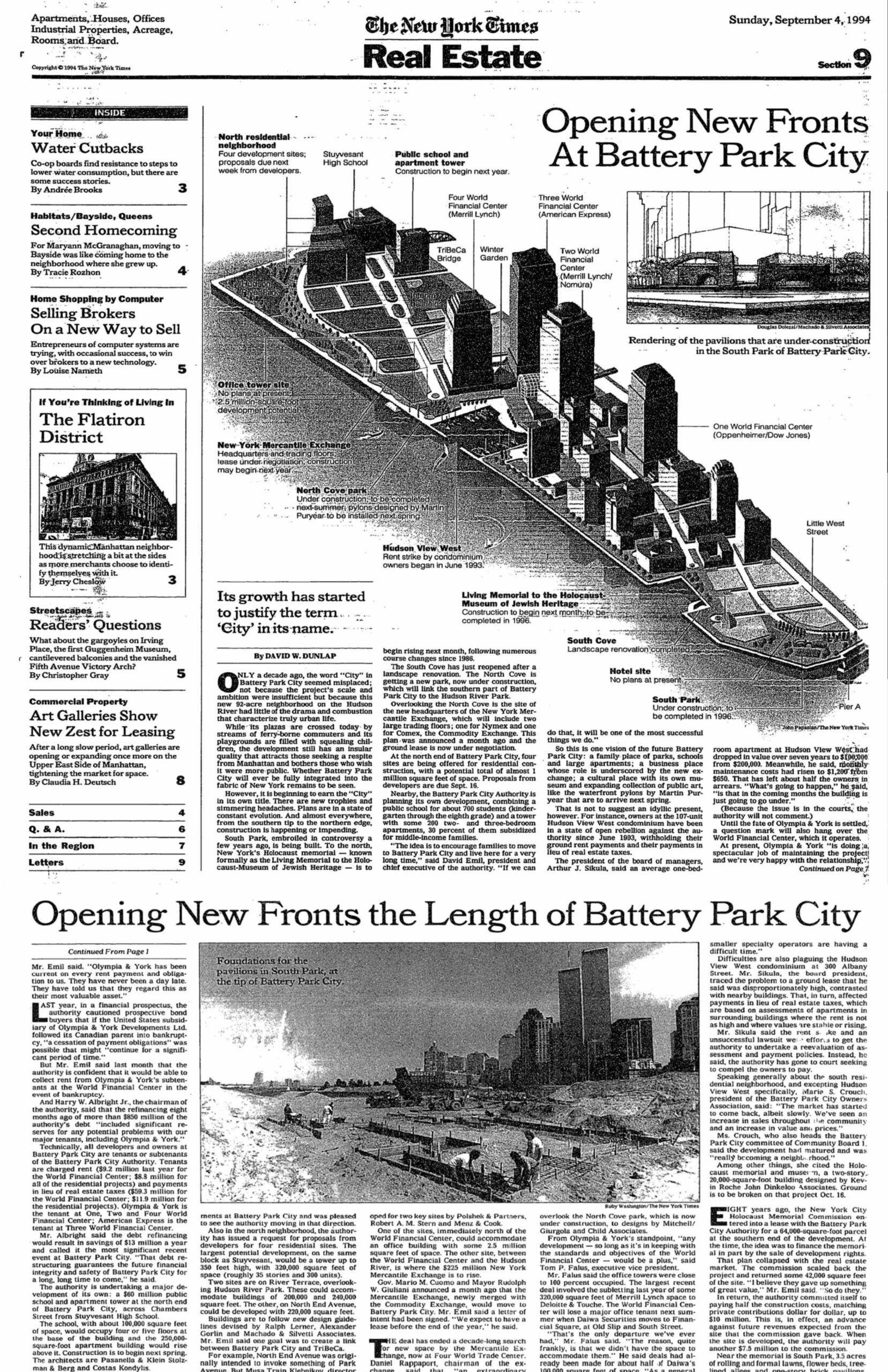

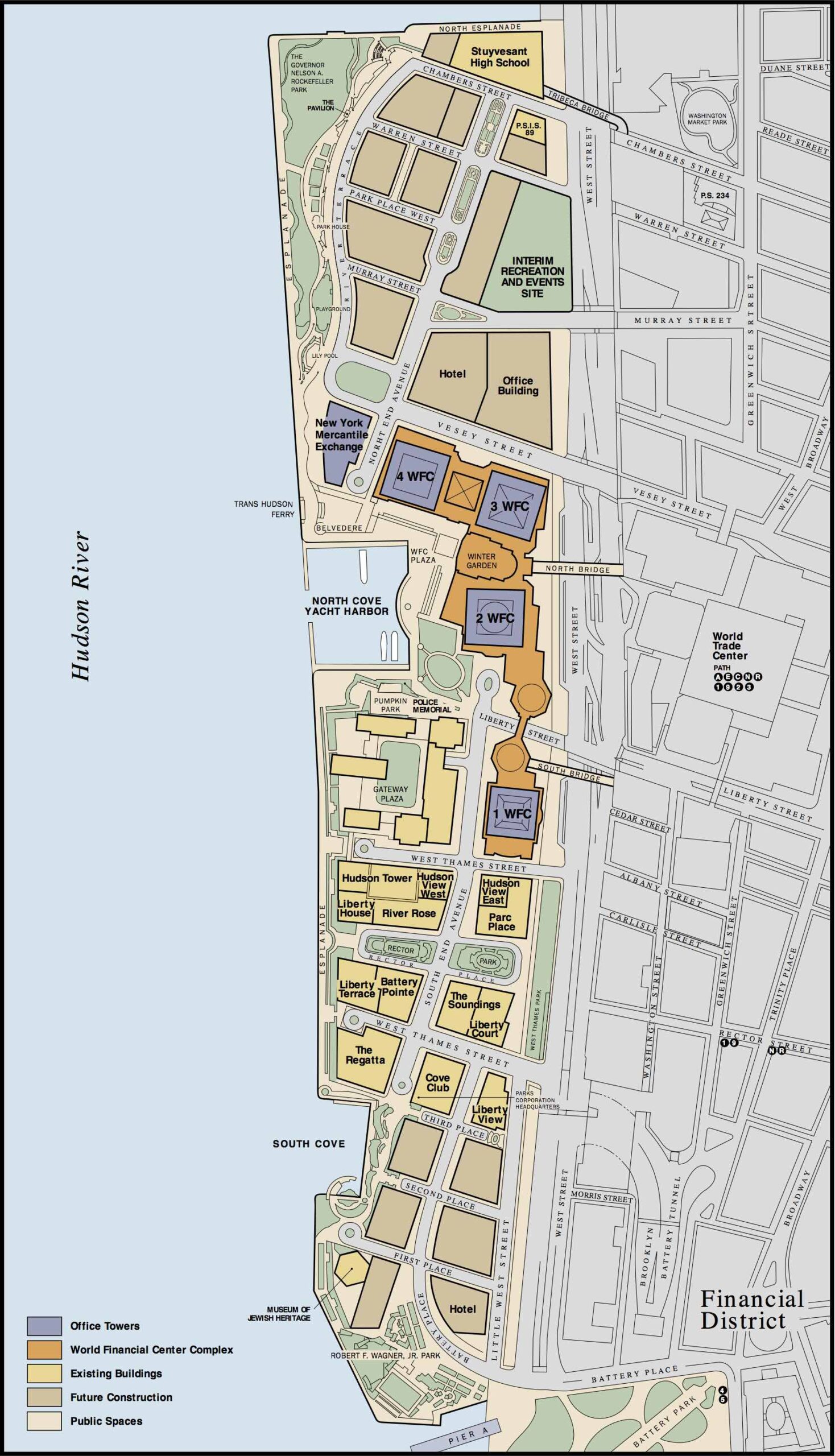

Battery Park City

The west side of lower Manhattan’s historic working waterfront, still ringed with a fringe of finger piers, was totally transformed in the last decades of the twentieth century by a landfill project that began with the excavations for the “bathtub” foundations of the World Trade Center.

From 1968, the Battery Park City Authority (BPCA), a government entity established by New York State, began to create 92 acres of new land that extended the Manhattan shoreline beyond the old wharves and into the Hudson. The concept was to develop a new community for downtown residents and to open up the waterfront to parks and public open space.

The Battery Park City Authority oversaw the creation of a master plan and the planning and construction of the infrastructure and parks. The individual buildings, however, were erected by private real estate companies who bid for the right to build on the land leased from the BPCA: this meant that the progress of the development depended on real estate cycles.

After several earlier schemes, a 1979 master plan by Cooper Eckstut guided the development of the first parcels of the project. Construction started at the center with the apartments of Gateway Plaza in 1983 and the commercial core of the four skyscrapers of the World Financial Center in 1985-1986.

Just south of this core, the first group of residential buildings, completed in 1986 and 1987, exemplified the master plan’s emphasis on place-making: design guidelines ensured variety and harmony through the prescribed massing of buildings and material palette and by limiting the areas of glass permitted.

In the North Neighborhood, Stuyvesant High School opened in 1992, but stood nearly alone until the first group of residential towers was completed shortly before 2000. Most early residential buildings in BPC were rentals, while those designed in the late 1990s and after were mostly condominiums. From 2000, in a pioneering role for environmental design, the BPCA established guidelines that required all new buildings to conform to LEED Green Building standards.

The large model, on loan from the Battery Park City Authority, shows Battery ParkCity today with all the building sites completed. The model dates back to 1998 and has been updated continuously, including with One World Trade Center and an early design for the 9/11 Memorial and Museum. A tower represented here on the site of the Deutsche Bank building remains undeveloped today. In contrast to the model, the photographic mural shows Battery Park City with the Twin Towers in the background, c. 2000. Large blocks of the North and South neighborhoods are still empty sites. The map to the left of the screen illustrates a contemporary master plan, with undeveloped lots in beige. The southernmost site, the future home of The Skyscraper Museum, is labeled “Hotel.”

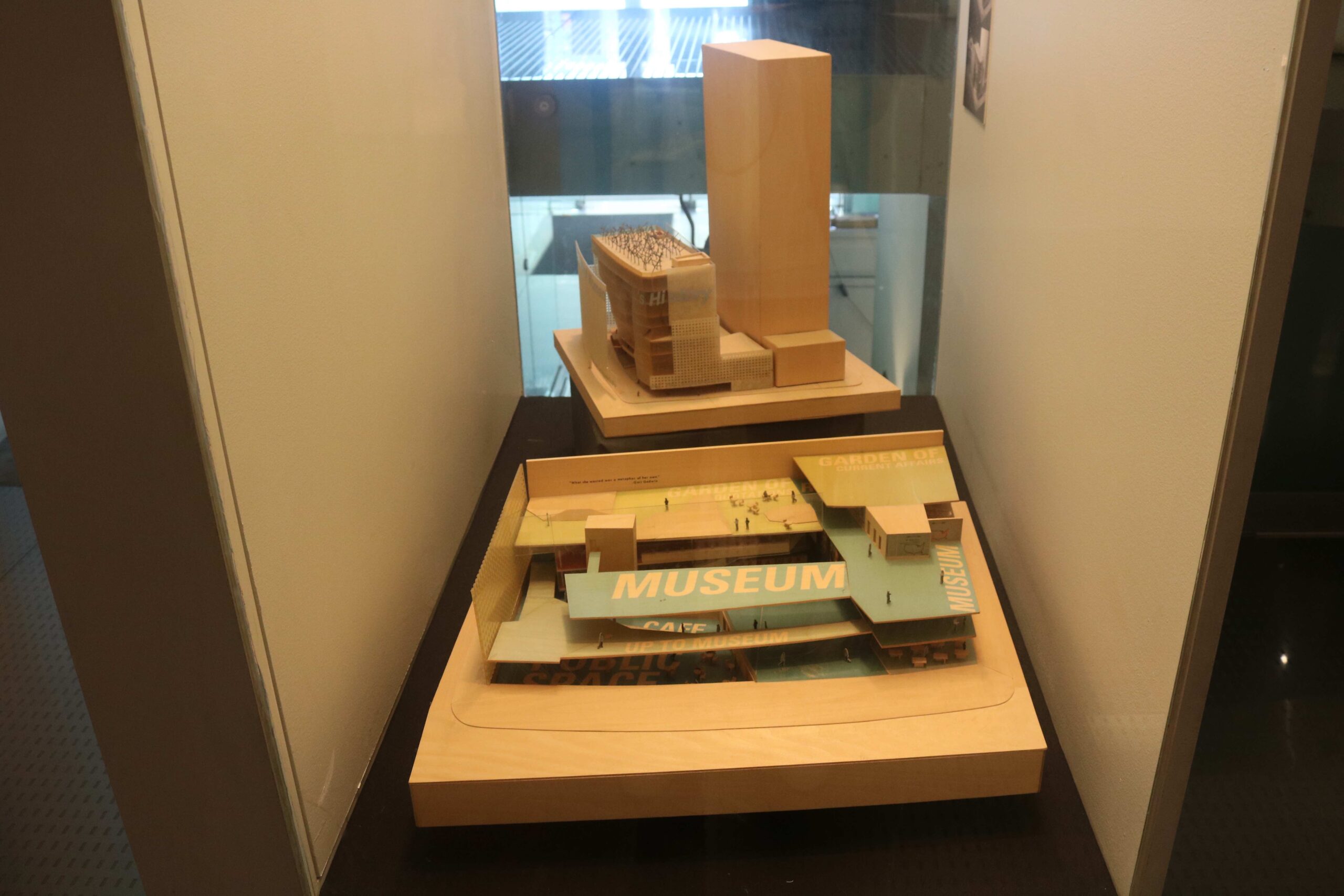

Wood Massing Model, 14” x 16” x 19”. Image, Wood Massing Model, 6.75 x 15”. Wood Ground Floor Model, 25” x 20” x 8”. On loan from Smith-Miller + Hawkinson

Museum of Women project info, 2002. Courtesy Smith-Miller + Hawkinson.

Museum of Women: Leadership Center

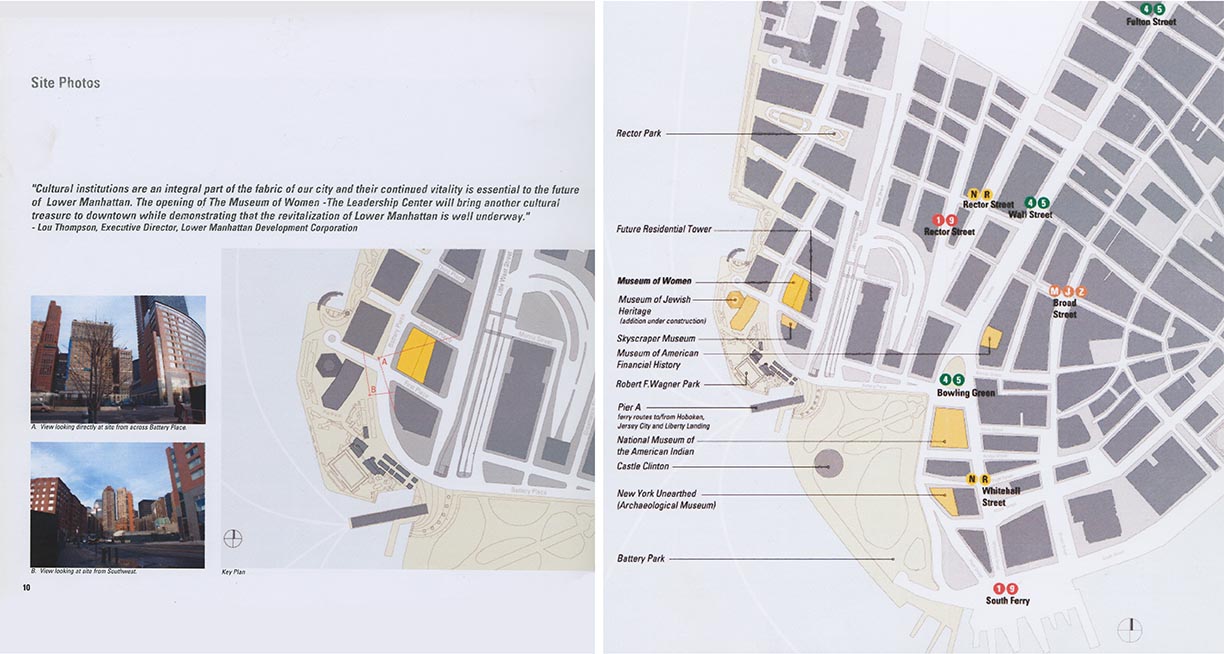

These models show the proposed Museum of Women: The Leadership Center, which would have occupied the site immediately north of The Skyscraper Museum where the school PS 276 now stands.

In 1998, Governor George Pataki established a commission to explore establishing an institution that would that would honor the contributions of women to American history and nurture new female leaders. By 2000, a both a program for a museum and the Battery Park City site were in place, and an architectural competition had produced five finalists. The commission was awarded to the firm Smith-Miller + Hawkinson. Their 9-story building included galleries and auditoriums for workshops and conferences, as well as a cafe and rooftop garden.

Fundraising for the museum was slow, however, and after 2007, when Governor Pataki left office, the site remained one of the last undeveloped lots in Battery Park City. Plans for the future school began, and the museum board and effort disbanded.

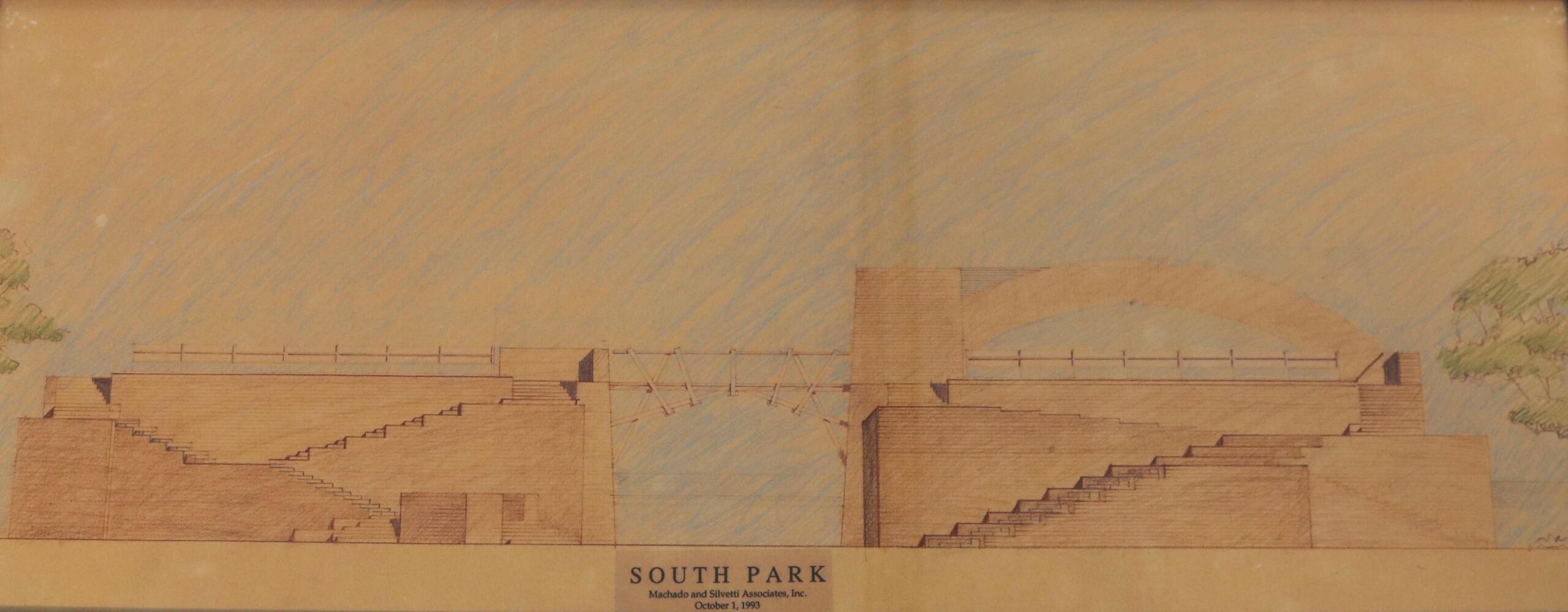

Model of early design for Wagner Park and Pavilion, 1993. Machado Silvetti, collection of Battery Park City Authority.

The model and framed drawing and in the case to the right are early schemes for the Robert F. Wagner Jr. Park and Pavilion, designed by the Boston-based firm Machado Silvetti. The park, directly across the street from The Skyscraper Museum, opened in 1996. The ensemble of architecture and landscape design, by Hanna/ Olin and garden designer Lynden B. Miller, features a grassy plane sloping down to the harbor and framed by two brick of pavilions joined by a wooden bridge. Rodolfo Machado describes the design in the statement on the right.

Watercolor drawing of Wagner Park Pavilion, October 1, 1993. Machado Silvetti, collection of Battery Park City Authority.

Wagner Park Pavilion at Sunset, c. 1996 ©Machado Silvetti

Robert F. Wagner, Jr. Park

The Robert F. Wagner, Jr. Park occupies a unique site characterized by its spectacular views of the Statue of Liberty and its relatively small area located at the center of colossal surroundings. The main function of this public place - the reason for its existence - is to provide a privileged viewing of the Statue of Liberty and the New York Harbor from a unique "point" along the New York waterfront.

The design of the park rests on three main components: a pair of allées that bring pedestrians from existing city sidewalks toward the main park entrance; a pair of pavilions connected by a bridge, constituting the main building; and a grass lawn framed by a continuous path and benches. This "Y" shaped architectural ensemble is the backbone of the park, resting in gardens that connect it to the Battery Park City Esplanade to the North and to Battery Park to the South.

The building is conceived as a large, over-scaled, massive masonry wall split in the center, framing (on approach) the view to the Statue. On the wall’s surfaces, a variety of brick patterns are displayed following a precise figurative symbolic strategy: the representation of a watchful, colossal, half-emerging face. This massive formation crumbles toward the city side to form a pair of large public steps that seemingly prolong the allées and bring the public up to a pair of balconies overlooking the lawn and harbor. From the center of the bridge connecting the two balconies, the viewer’s position relative to the Statue of Liberty is "face to face," direct.

This perspective drawing of the Plaza records an important moment along the design process, when we were freely playing with the Statue's attributes as material for the design of the space. Thus, the book-like paved ground represents the book in Liberty's hand, its pages becoming steps, etc.

The pavilions had, at some point, a pergola like canopy, such as the ones used in the excavation of ruins to protect them from the sun. We had a profound and rewarding dialogue with David Emil, then CEO of BPCA, and with Laurie Olin, our Landscape Architect, friend and Harvard colleague at that time. Often the late Mickey Friedman, Art Advisor, and Herbert Muschamp, the New York Times Architecture Critic, were part of the conversation as well. It was a splendid design process, of the kind rarely experienced today in designing significant public places.

Rodolpho Machado

HISTORIC CORE

In the postwar era, Midtown development challenged Downtown as the city’s principal business center and won. As new skyscrapers began to frame Park, Third, and Sixth avenues, many banks and large companies relocated to Midtown, emptying the historic core. Aging office buildings in the Financial District, including many skyscrapers of the 1910s and ‘20s, began to slide down-market. The stock market crash of 1987 and the savings-and-loan crisis brought a recession to New York commercial real estate markets that produced, in the mid-1990s, a vacancy rate Downtown above 30 percent and a total of 25 million square feet of office space unrented.

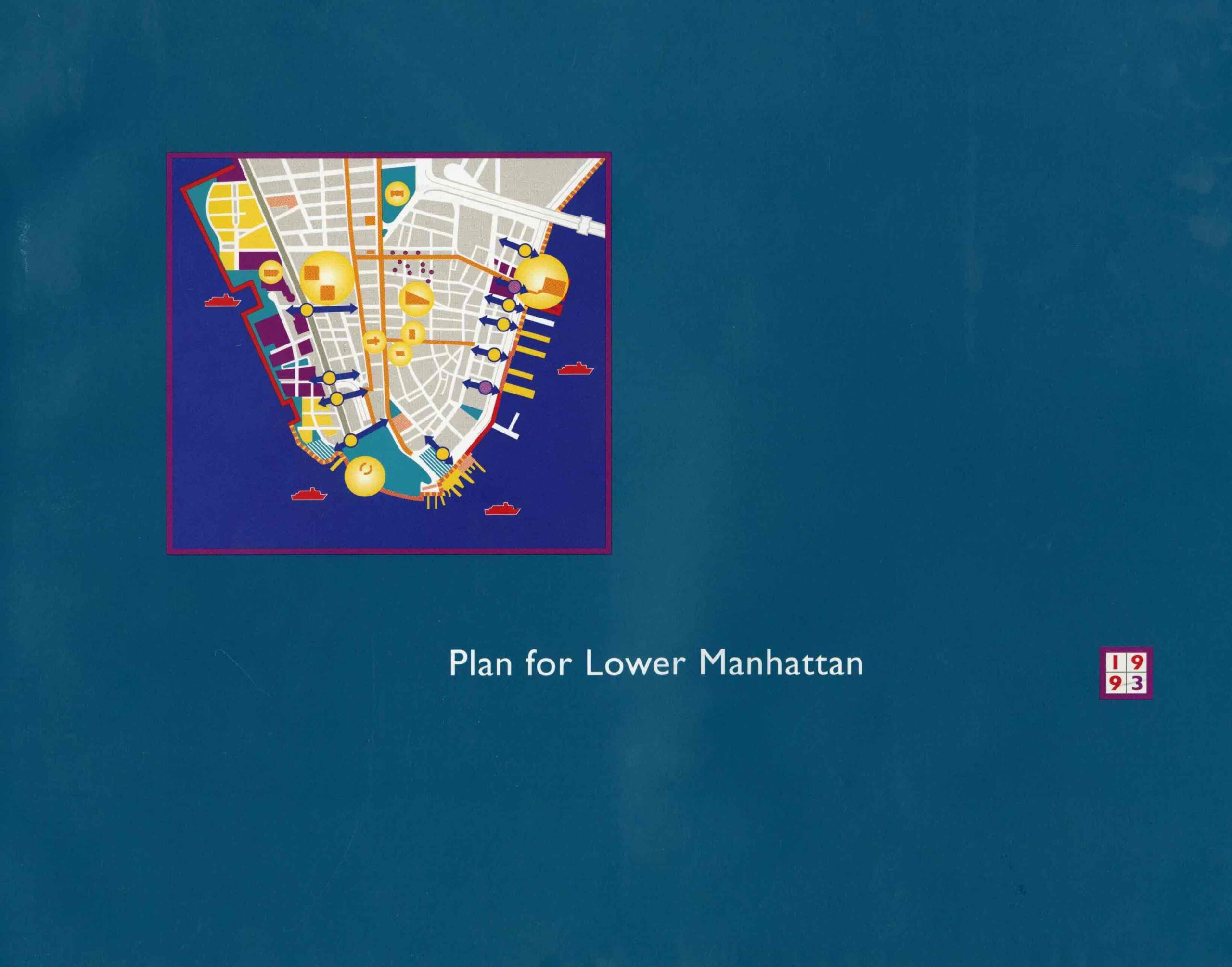

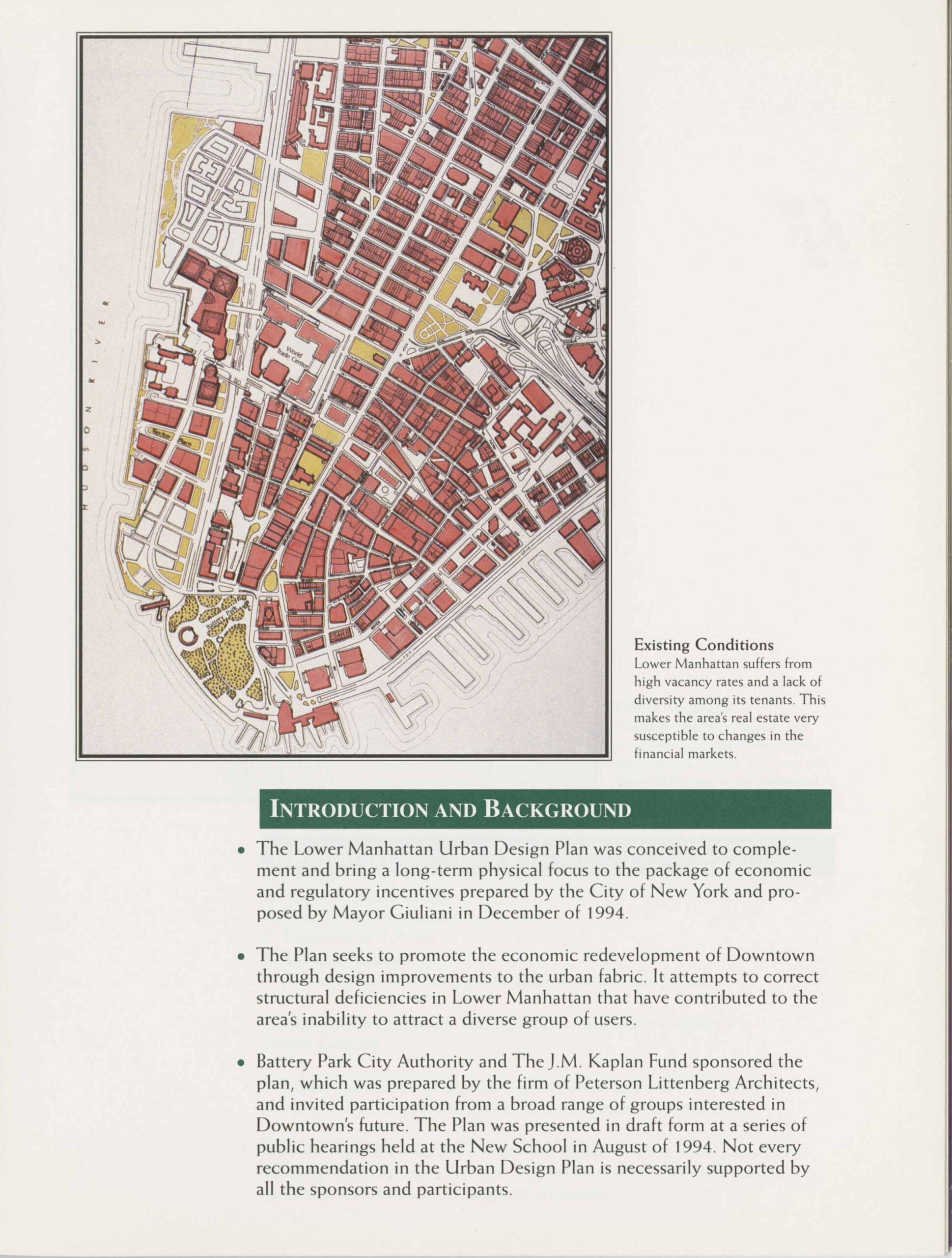

The City tried to address these problems with public policy initiatives. In 1993, the Dinkins Administration and the Department of City Planning issued its Plan for Lower Manhattan, shown below with its blue cover and an interior page, which analyzed the assets and challenges of Downtown and called for its reinvention as a more diversified “24/7” neighborhood.

Promoting the conversion of office buildings to residential use was a key concept, but developers were slow to respond. In 1994, the new Giuliani Administration and its Chairman of the Planning Commission Joseph Rose advanced a package of economic and regulatory incentives that encouraged reinvestments in older buildings, including a 14-year abatement on property taxes for office buildings converted to apartments. Federal historic preservation tax credits were also available for buildings that were designated landmarks or were placed on the National Register: this policy helped to soften building owners’ resistance to LPC regulation. Zoning changes legalized “live-work” spaces of the sort that appealed to entrepreneurs and artists, as in Soho and Tribeca.

The best candidates for residential conversion were not the older low-rise structures of 10 to 20 stories that lined the dense, dark “canyons” of the district, but the taller towers, mostly of the Twenties, that had good light, great views, and smaller floor plates that adapted to apartment floor plans. As illustrated in the image below, a study by Michael Kwartler and the New School’s Environmental Simulation Center, employed the then-new 3D geographic information system (GIS) to visualize statistics about Lower Manhattan and to create an digital model using data related to zoning, census, infrastructure, building construction and age, total floor area, and vacancy rates.

The image, which was published in the New York Times in a David Dunlap article, “Bringing Downtown Back Up,” (reproduced below) illustrated the amount of office space in pre-war buildings 150 ft. or more above the street – space that, at that time, was both primarily vacant and highly suitable for apartments. Another feature on the future of residential conversion in the Financial District, “Wall Street Wonderland,” appeared New York Magazine in November 1996.

Other city agencies, such as the New York City Economic Development Corporation (EDC) and State entities such as the Port Authority and the Battery Park City Authority, as well as professional and civic groups such as the Regional Plan Association and the Landmarks Conservancy, trained attention on transforming the district. One study funded and by the BPCA that received support from the J.M. Kaplan Fund was Peterson Littenberg Architects’ “Lower Manhattan Urban Design Plan” (middle frame) which “sought to promote the economic development of Downtown through design improvements to the urban fabric.” The plan was presented at a series of public hearings at the New School in August 1994.

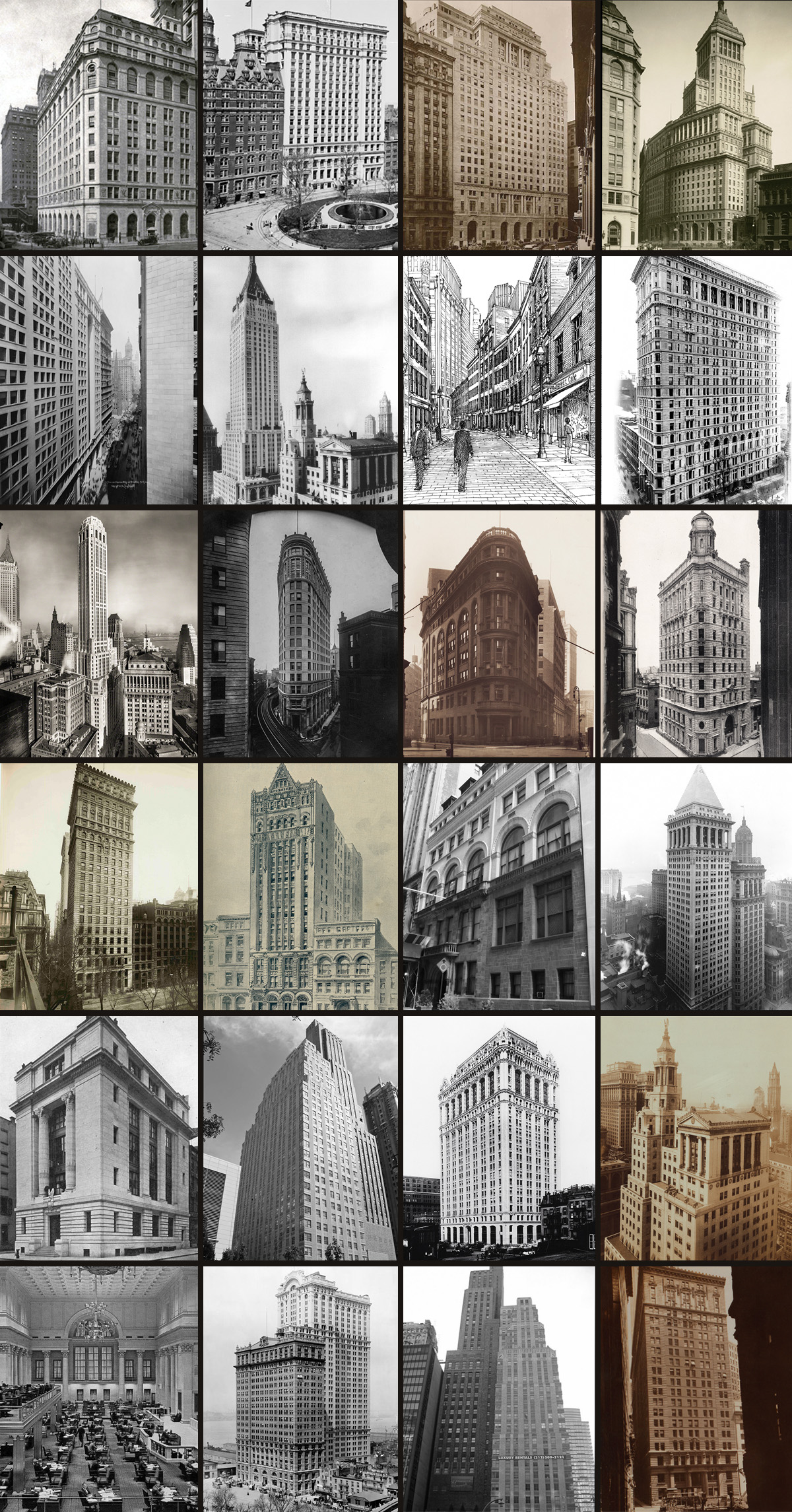

Landmarks

A signal achievement of government in lower Manhattan in the second half of the 1990s was the addition of twenty-four new individual landmarks and one new historic district, Stone Street, designated between 1995 and 2001 by the Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC). Seventeen of these were skyscrapers of the 1910s to 1930s, mostly in the Financial District. This was an area and building type that had long resisted LPC regulation, which building owners regarded as a threat to their control over their property and to what might be even more valuable – the land that, if demolished, the structures had previously occupied.

In the real estate slump of the Nineties and under the Chairmanship of Jennifer Raab from 1994 to 2001, arguments for landmark designation had a new logic. The City began to put in place policies that incentivized the restoration and interior upgrades of older office buildings, as well as their conversion to residential use. Buildings that were designated NYC landmarks or were added to the National Register were further eligible for federal historic preservation tax credits, as well as for City tax breaks.

To the total of fifty-one individual landmarks and three historic districts currently designated in this area, twenty were added from 1995 to 2001. Images and IDs for those landmarks are shown on this wall.

1995

1. International Mercantile Building, 1 Broadway

2. Bowling Green Of ce Building, 11 Broadway

3. Cunard Building, 25 Broadway

4. Standard Oil Building, 26 Broadway

5. American Express Co. Building, 65 Broadway

6. Manhattan Company Building, 40 Wall St.

1996

7. Stone Street Historic District

8. Empire Building, 71 Broadway

9. City Bank Farmers Trust, 20 Exchange Pl.

10. Beaver Building, 82-92 Beaver St.

11. Delmonico’s Building, 56 Beaver St.

12. J. & W. Seligman & Co. Building, 1 Williams St.

1997

13. American Surety Building, 100 Broadway

14. 56 - 58 Pine Street

15. Downtown Association Building, 60 Pine St.

16. Banker’s Trust Building,14 Wall St.

17. American Bank Note Co. Building, 70 Broad St

1998

18. 21 West Street Building

19. West Street Building, 90 West St.

20. Bank of New York and Trust Co., 48-50 Wall St.

1999

21. Wall Street Interior, 55 Wall St.

2000

22. Whitehall Building, 17 Battery Pl.

23. Downtown Athletic Club, 19 West St.

24. Broad Exchange Building, 25 Broad St.

2001

25. 1 Wall Street Building (not pictured)

The video above, created to celebrate the twentieth anniversary of the founding of the Alliance for Downtown New York, documents the organization’s founding and history. Courtesy of Alliance for Downtown New York.

The Downtown Alliance

Founded in 1995, the Alliance for Downtown New York brought the vehicle of the Business Improvement District (BID), already used in Midtown and Times Square, to lower Manhattan. As one of the BID's founders, real estate developer Bill Rudin, phrased the situation in the video shown above: “The Alliance was born out of, basically, fear. We had 30 million feet of vacant space out of an inventory of 100 million feet.” High office vacancy rates downtown compounded problems on the street, including empty storefronts, early closing hours, and increasing crime. Like all BIDS, the Alliance was funded by a small tax assessment on building owners and focused on the business environment by organizing sanitation and security on the streets, as well as marketing, capital improvements, and lobbying the City government on behalf of local business interests. The Alliance was also an active player in turning its district into a more residential neighborhood, as it helped aging skyscrapers convert to residential buildings. Since the 1990s, the Alliance has grown to include other services, such as free transportation, in its rehabilitated district.

Stone Street Historic District

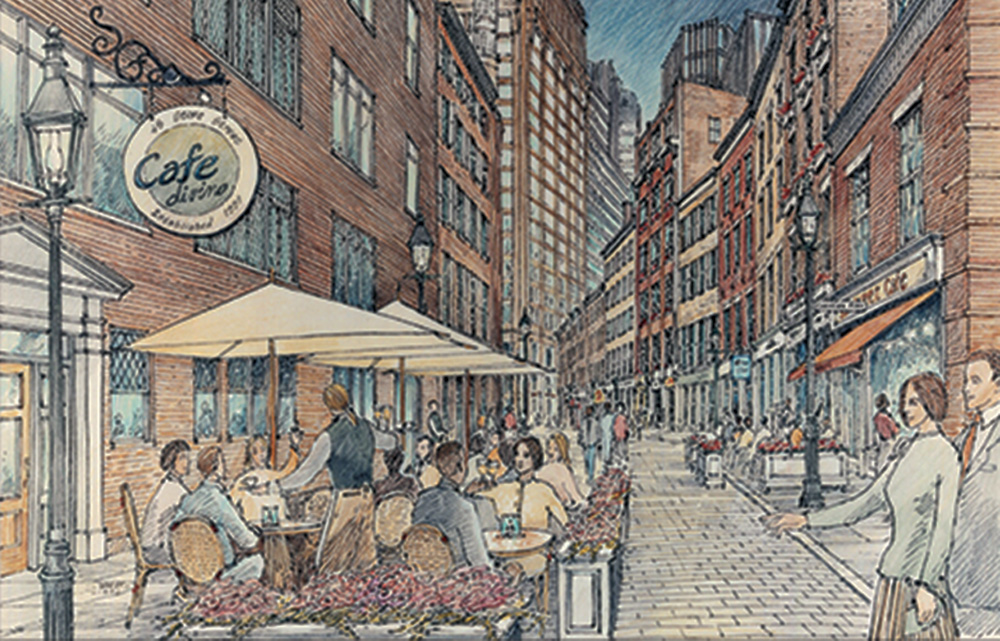

Stone Street, which runs for three blocks from Hanover Square to Broad Street, was one of the colonial city’s first paved streets, laid out by Dutch colonists in the 1600s. It had survived, mostly unchanged, as a low-rise enclave of early nineteenth-century brick counting houses and warehouses. But in the Nineties, its storefronts were rundown and vacant, and the area was plagued with drug dealers.

The young Downtown Alliance undertook a project to restore the buildings and return the street to life as an area of restaurants and retail. In 1996, partnering with the Landmarks Preservation Commission to designate Stone Street as a historic district, as well as with the city's Department of Transportation and Department of Design and Construction, the Downtown Alliance coordinated the Stone Street reconstruction with federal funds and historic preservation tax credits. The city installed a new street bed lined with cobblestones duplicating the street's original paving, as well as laid new bluestone sidewalks, a granite curb, and nineteenth-century style street lamps.

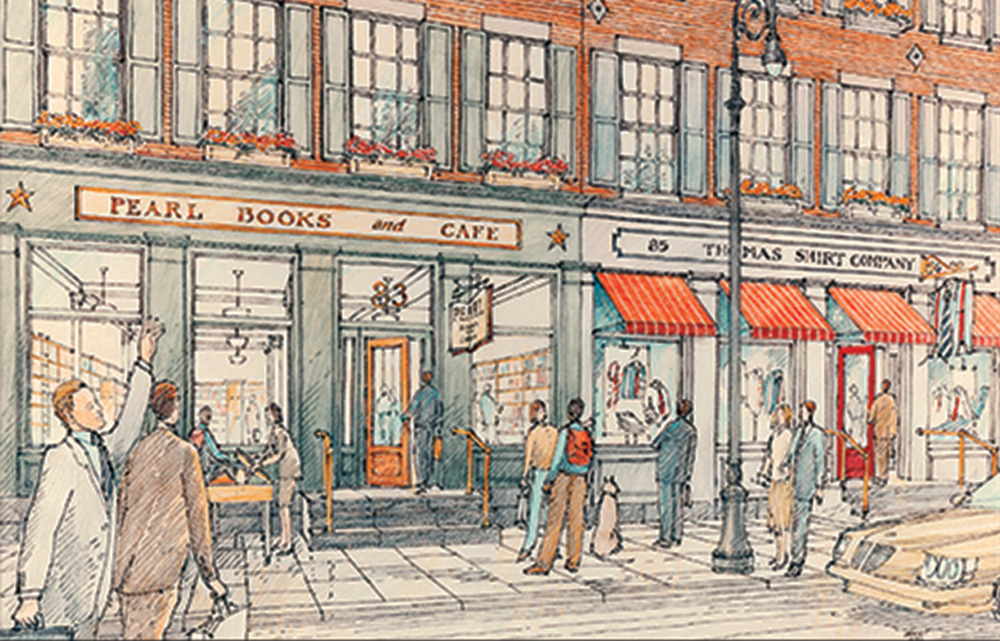

The plans for the restoration were designed by Beyer Blinder Belle, whose drawings, rendered by Kevin Woest, illustrated the goal, as well as documented the “after” photographs here. Today, Stone Street attracts crowds to its restaurants and bars and popular summertime sidewalk cafes.

Wall Street Trading

“Wall Street” is at once a specific place, a metaphor for lower Manhattan’s entire financial district, and a term that refers broadly to the U.S. financial services industry and marketplace. At the center of this system for more than 200 years has been the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE), located at 11 Wall Street, according to the address of its narrow entrance there, but fronting far more monumentally, as a temple of trading, on Broad Street just south of the intersection of Wall Street. Through the 1980s, the “Big Board,” as the NYSE is still known, dominated the trading of stocks and securities with a 90 percent share of the market. Today only 14 percent of daily volume is traded on the NYSE.

Challenges to the dominance of the NYSE in the 1990s came principally from electronic and high-frequency trading and from the rise of a global marketplace. In this environment of computers and continuous world markets, the place-based NYSE opening bell, human market makers, and traditional trading posts were archaisms.

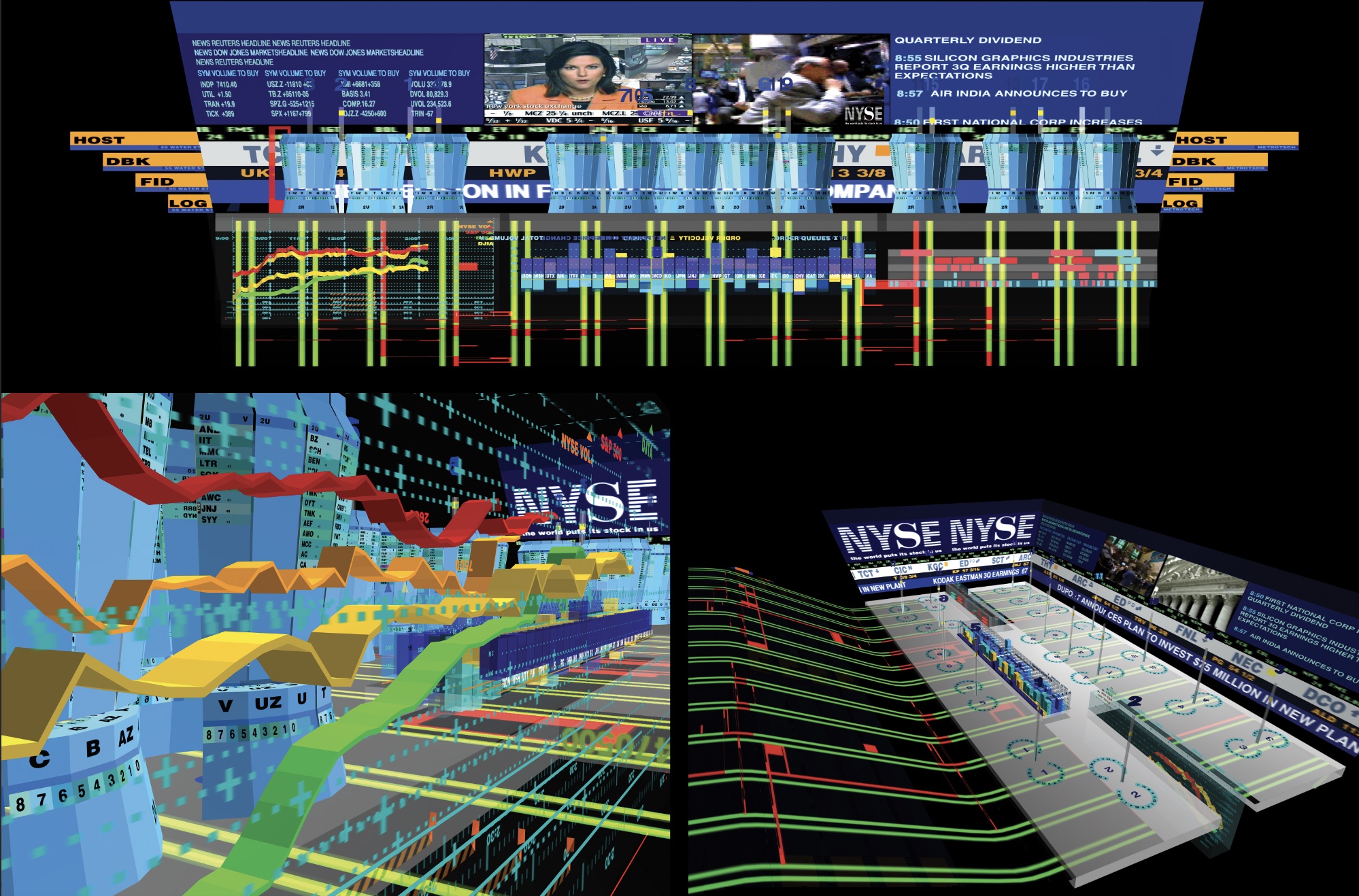

In 1999, the NYSE commissioned the Studio Asymptote to move them toward the 21st century by designing a model for the Advanced Trading Floor, a “state-of-the-art command center” constructed adjacent to the main space, which answered the NYSE’s need to update its facilities and accommodate the virtual-exchange model and interface. In addition, Asymptote principals Hani Rashid and Lise Anne Couture designed a Virtual Trading Floor, which they described as “a dynamic 3D view of shares and financial information, a fully interactive space containing stock exchange values, indexes, graphs, news and live video content from major television networks, which change “ floating” in real time within an architectural environment.” Their renderings are reproduced on the case opposite.

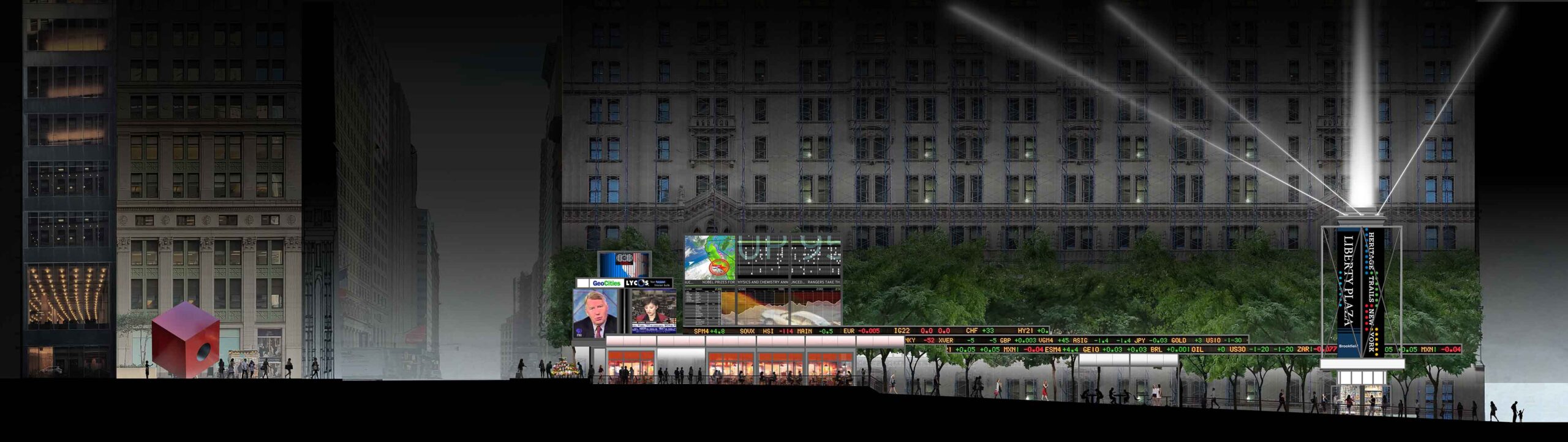

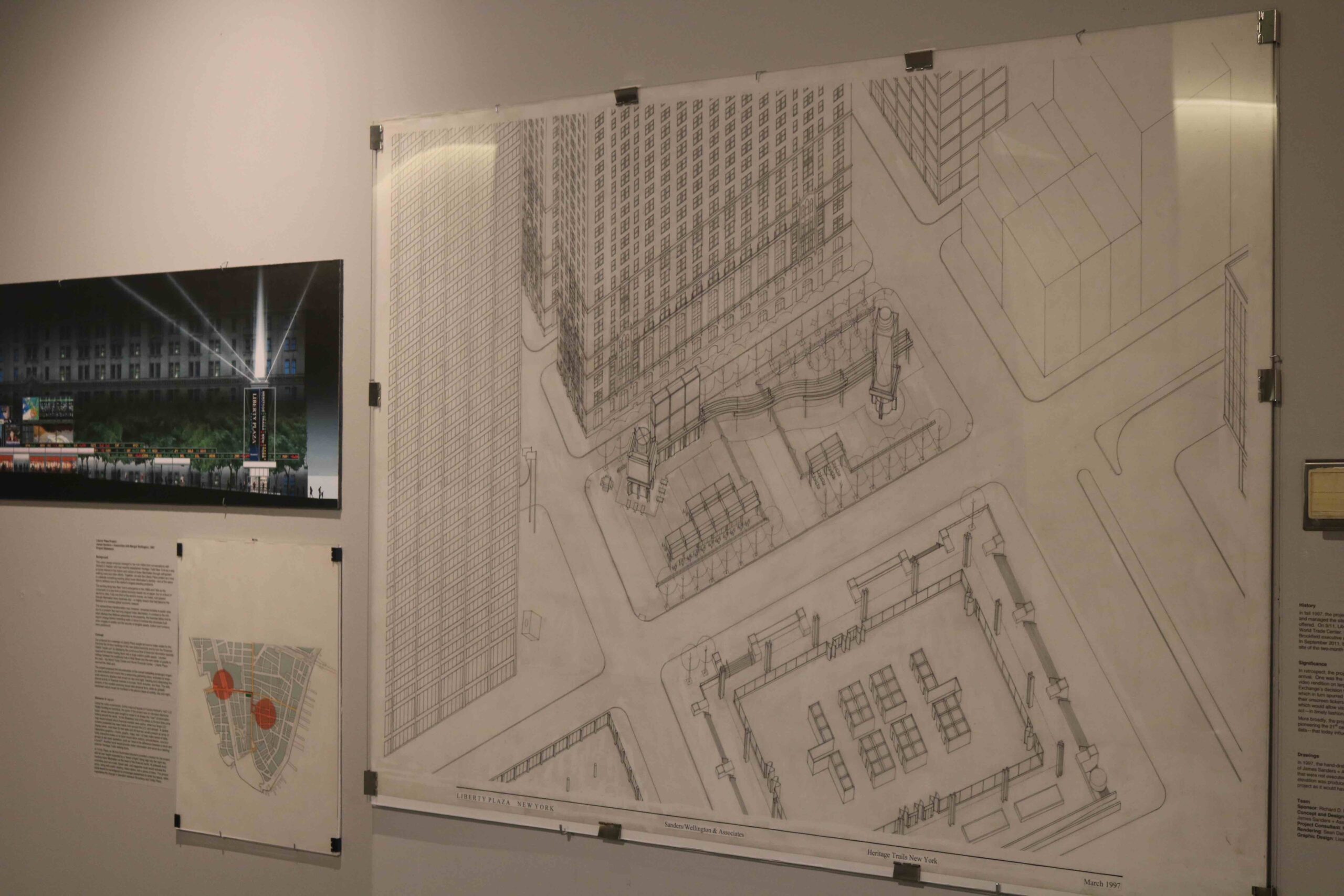

Team

Sponsor: Richard D. Kaplan, Heritage Trails New York

Concept and Design: James Sanders, AIA; Jean McGinty

James Sanders + Associates

Project Consultant: Margot Wellington

Rendering: Sean Daly, Windtunnel Visualization

Graphic Design: Lisa Strausfeld, Information Art

Liberty Plaza Project

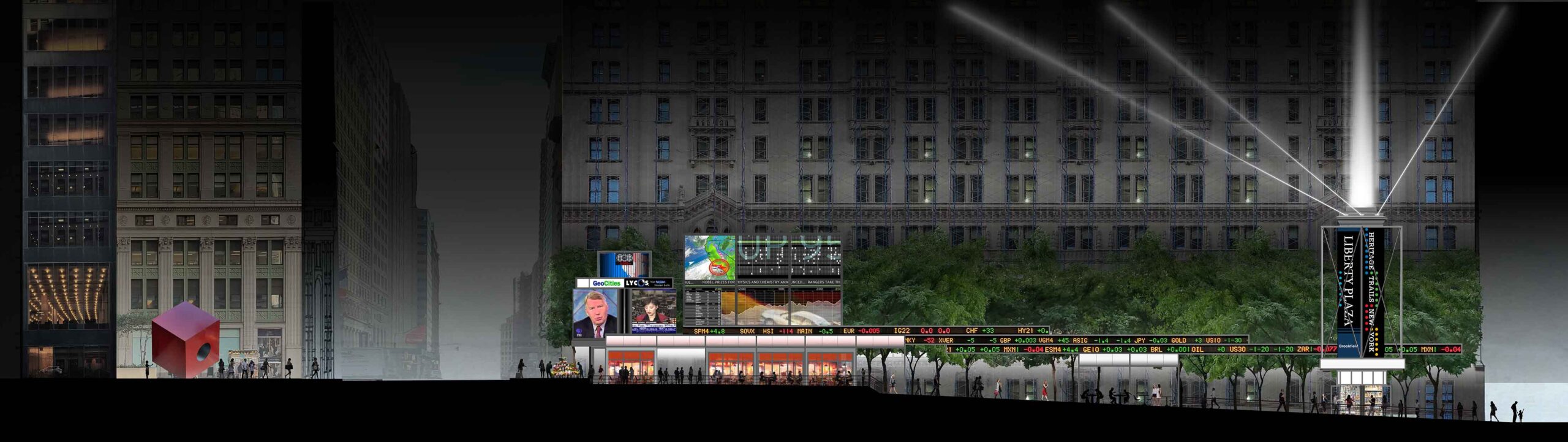

The idea of the flow of electronic information and a worldwide network of markets, centered in lower Manhattan, was key to the important, but unrealized concept for the redesign of Liberty Plaza proposed by architect James Sanders and conceived in collaboration with Richard D. Kaplan, the founder of Heritage Trails New York. His original 1997 axonometric drawing is displayed on this wall alongside a new colorized rendering of the digitized original line drawing of a long cross section of Liberty Plaza, which stretches the block between Broadway (on the left) and Trinity Place/ Church Street (to the right). Sanders had always intended to add color to the drawing to evoke a night view that would make clear the important role light plays in the project, both in the flashing TV screens of worldwide market reports and in a cluster of beams that established a vertical axis at the east end of the plaza, issuing from a structure that was to serve as an information hub for Heritage Trails.

As Sanders explains in the Project Statement below, the ambition of the scheme was “to turn the Financial District “inside out” by displaying the continuous flow of financial information, typically reserved for interior trading floors, in a large outdoor public space.” It proposed to remedy the problems of the existing urban design of the 1960 zoning-bonus plaza and to re-center the image of “Wall Street” as a public square located between the traditional hub of the NYSE and the new financial center of gravity to the west, the World Trade Center and World Financial Center (now renamed Brookfield Place).

Background

This urban design proposal emerged in the mid-1990s from conversations with Richard D. Kaplan, who had recently established Heritage Trails New York as a way to boost interest in the history and culture of lower Manhattan through self-guided walking tours and other efforts. Together, we saw the Liberty Plaza project as a way to celebrate something exciting about lower Manhattan’s identity—and, at the same time, address one of the district’s longest standing problems. The exciting thing was New York’s emergence in the 1980s and ‘90s as the crossroads of a new kind of global economy, based not on paper, but on a flood of electronic data. Fully one third of the world’s money, we noted, now passed through Manhattan every business day —a mighty stream that had become the lifeblood of a nonstop global economic network. This extraordinary transformation had, however, remained invisible to public view due to a problem that had long plagued lower Manhattan. In contrast to the rich retail displays that Midtown presented to the passerby, the financial district hid its electric energy behind forbidding walls of stone in fortress-like structures built when images of solidity and the security of tangible assets—bullion and currency—were paramount.

Concept

Our proposal for a redesign of Liberty Plaza sought at once to make visible, for the first time, the 24-hour workings of the new global economy and to turn the Financial District “inside out” by displaying the continuous flow of financial information, typically reserved for interior trading floors, into a large outdoor public space. Located halfway between the traditional hub of Wall Street and the new center of gravity to the west – the World Trade Center and World Financial Center – Liberty Plaza seemed the ideal spot. The project proposed the reconstruction of the current forbidding landscape, ringed by steel bollards and chains, into a welcoming gathering place, activated by large-scale electronic displays that would run day and night, tracking and interpreting the diurnal activity of financial markets in Europe, North America, and Asia as they activated around the world. The data streams of the modern economy would take physical urban form, while its globally interlinked nature would be manifest in the plaza’s continual blaze of activity—across the day, late into the night, and into the day again.

Drawings

In 1997, the hand-drafted drawings presented here were prepared by Jean McGinty of James Sanders + Associates, to serve as the basis for digital color renderings that were not executed at the time. For this exhibition, a rendering of the north elevation was produced by Sean Daly of Windtunnel Visualization, representing the project as it would have looked in the late 1990s.

Elements & Layout

Using the richly ornamented, Gothic-inspired façade of Francis Kimball’s 1907 U.S. Realty Building as backdrop, the spine of the project was an elevated electronic ticker, whose sinuous path sought to evoke in its shape the “river” of information flowing around the world. At the Broadway end of the plaza, a 24-hour time-zone map would indicate which financial markets were active, while four large LED screens presented live news feeds from around the U.S. and abroad. A central display panel, more than 50 feet wide and 20 feet tall, would present an array of interpretive graphics—charts, graphs, maps, text—to help make sense of data, while interactive kiosks at its base would allow visitors, schoolchildren, and tour groups to ask basic questions, such as “what is the difference between a stock and a bond?” Another kiosk would provide visitor information and serve as a starting point for Heritage Trails walking tours. At Trinity Place, an 80-foot illuminated structure provided a marker for the project, with its own height extended by a “tower of light” rising high into the night sky, marking lower Manhattan as the heart of the financial world. At sidewalk level, amenities such as a café, flower stall, and magazine kiosk would activate the plaza, along with public seating, chess tables, and a grove of trees. The ground plane would be reconfigured to encourage pedestrians to enter the space, while negotiating the change in elevation between Broadway and Trinity Place.

History

In fall 1997, the project was presented to Brookfield Properties, which owned and managed the site, and to NASDAQ and CNBC, but no commitment was offered. On 9/11, Liberty Plaza was severely damaged by the collapse of 2 World Trade Center. It was subsequently rebuilt as “Zuccotti Park,” in honor of Brookfield executive and former City Planning Commission Chair John Zuccotti. In September 2011, the plaza became the focus of worldwide attention as the site of the two-month “Occupy Wall Street” protest.

Significance

In retrospect, the project embodied several crucial advances at the moment of their arrival. One was the then-recent invention of the three-color LED, allowing full-color video rendition on large outdoor displays. Another was the New York Stock Exchange’s decision to release stock prices without a proprietary 15-minute delay, which in turn spurred the creation of 24-hour cable business-news networks with their onscreen tickers. The last was the introduction of stock trading via cellphones, which would allow visitors to Liberty Plaza, while lounging at its café or a bench, to act—in timely fashion—on the information streaming above their heads. More broadly, the project celebrated the role of New York, and lower Manhattan, in pioneering the 21st century global commercial culture—fueled by endless streams of data—that today influences nearly every aspect of everyday life.

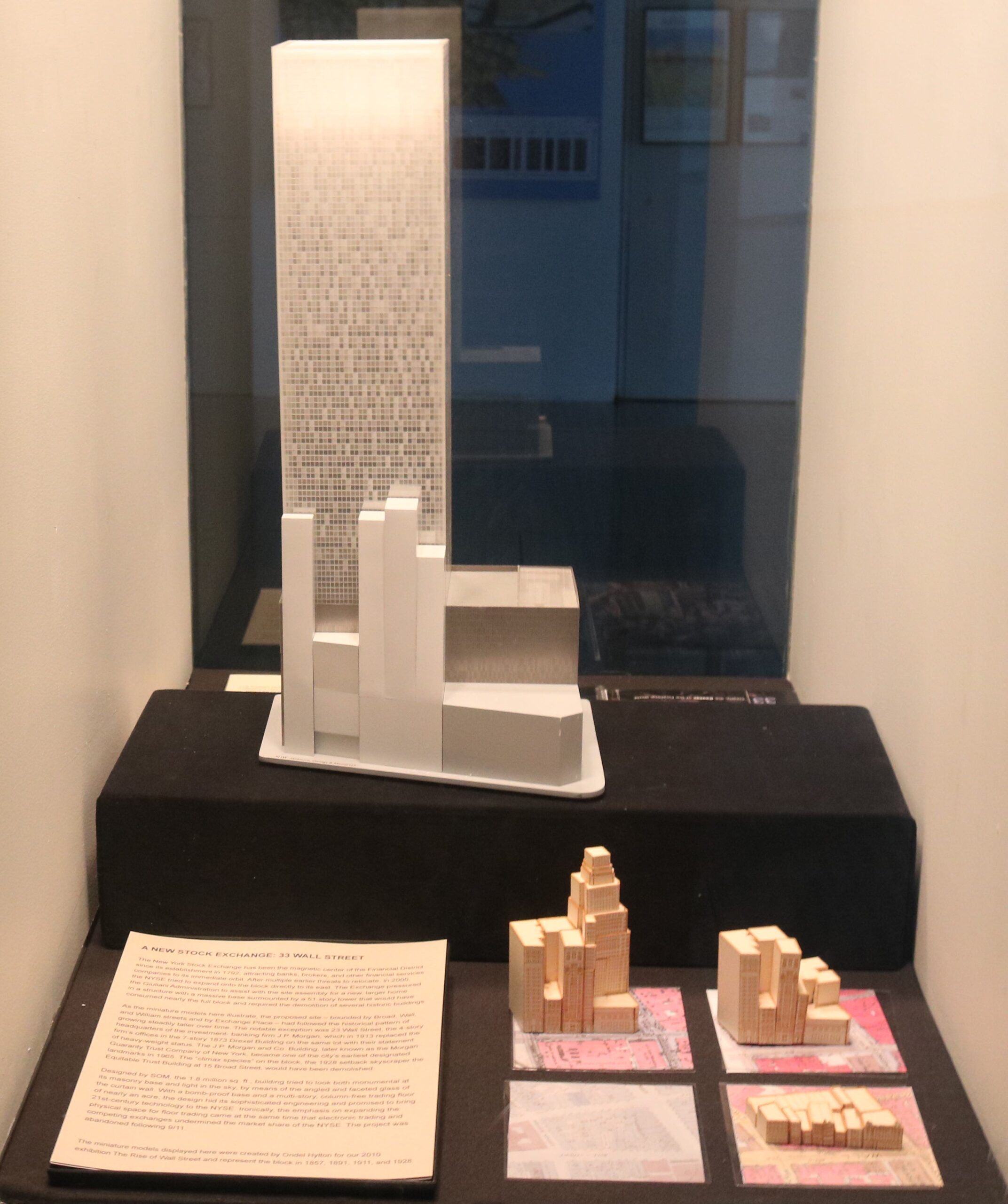

Model of proposed 33 Wall Street, Skidmore, Owings & Merrill.

The miniature models displayed here were created by Ondel Hylton for our 2010 exhibition The Rise of Wall Street and represent the block in 1857, 1891, 1911, and 1928.

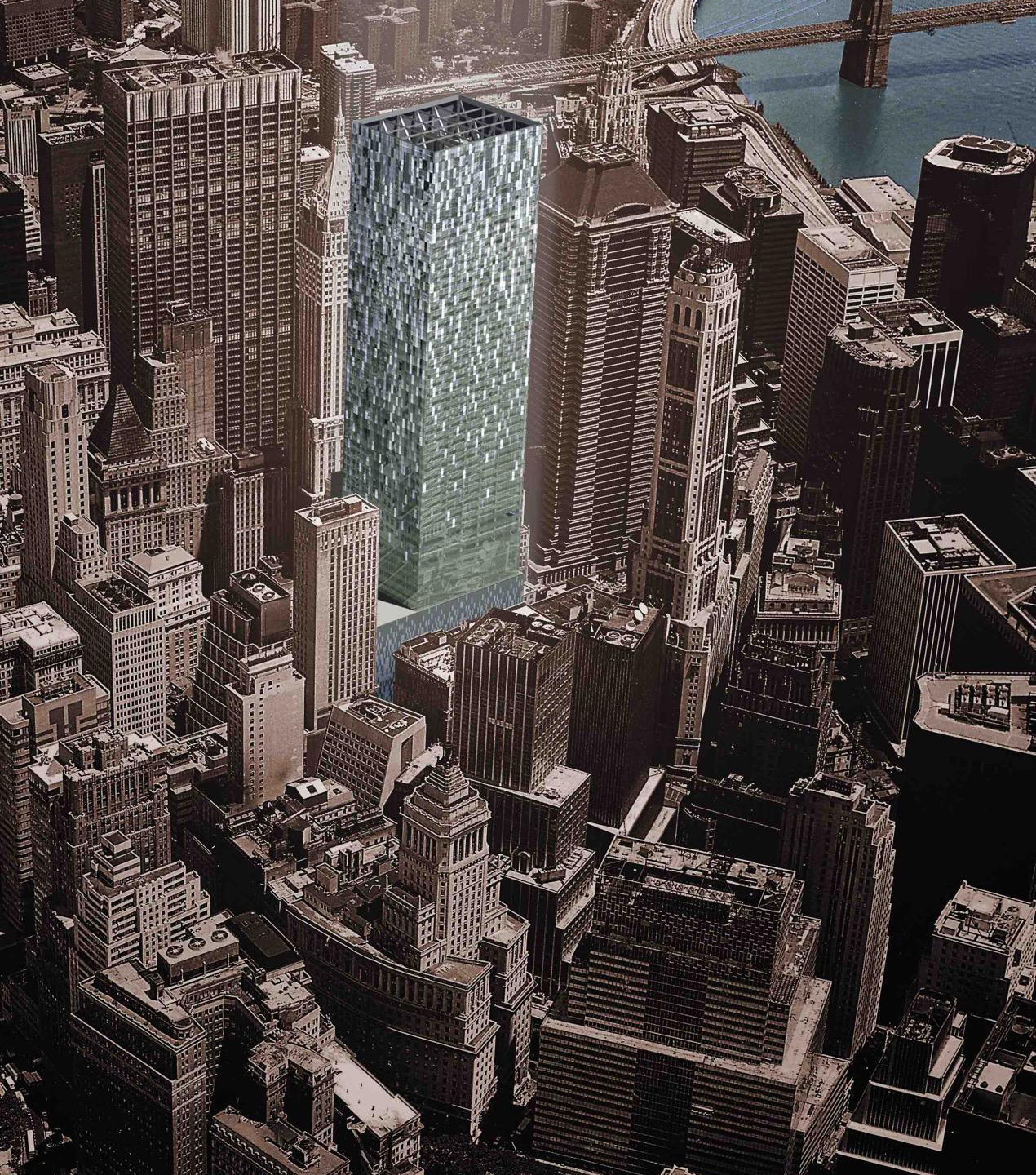

Unbuilt proposal for a new home for the New York Stock Exchange, with a 51-story, 1.4 million sq. ft. office tower above, 2000. Designed by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, LLP; David Childs, principal architect.

A New Stock Exchange: 33 Wall Street

The New York Stock Exchange has been the magnetic center of the Financial District since its establishment in 1792, attracting banks, brokers, and other financial services companies to its immediate orbit. After multiple earlier threats to relocate, in 2000, the NYSE tried to expand onto the block directly to its east. The Exchange pressured the Giuliani Administration to assist with the site assembly for a new, larger home in a structure with a massive base surmounted by a 51-story tower that would have consumed nearly the full block and required the demolition of several historic buildings.

As the miniature models here illustrate, the proposed site – bounded by Broad, Wall, and William streets and by Exchange Place – had followed the historical pattern of growing steadily taller over time. The notable exception was 23 Wall Street, the 4-story headquarters of the investment-banking firm J.P. Morgan, which in 1913 replaced the firm’s offices in the 7-story 1873 Drexel Building on the same lot with their statement of heavy-weight status. The J.P. Morgan and Co. Building, later known as the Morgan Guaranty Trust Company of New York, became one of the city’s earliest designated landmarks in 1965. The “climax species” on the block, the 1928 setback skyscraper the Equitable Trust Building at 15 Broad Street, would have been demolished.

Designed by SOM, the 1.8 million sq. ft., building tried to look both monumental at its masonry base and light in the sky, by means of the angled and faceted glass of the curtain wall. With a bomb-proof base and a multi-story, column-free trading floor of nearly an acre, the design hid its sophisticated engineering and promised to bring 21st-century technology to the NYSE. Ironically, the emphasis on expanding the physical space for floor trading came at the same time that electronic trading and competing exchanges undermined the market share of the NYSE. The project was abandoned following 9/11.

The miniature models displayed here were created by Ondel Hylton for our 2010 exhibition The Rise of Wall Street and represent the block in 1857, 1891, 1911, and 1928.

THE EAST RIVER WATERFRONT

While the ‘urban renewal’ of the west side of lower Manhattan added a whole new layer of land to the Hudson River shoreline in the form of Battery Park City, similar plans for the East River waterfront failed to move forward. By the mid-1990s, the area had a split personality. The southern end of Water Street had been developed with bulky superblock skyscrapers such as 1 New York Plaza (1969) and 55 Water Street (1972), at the time, the world’s largest privately-developed office building.

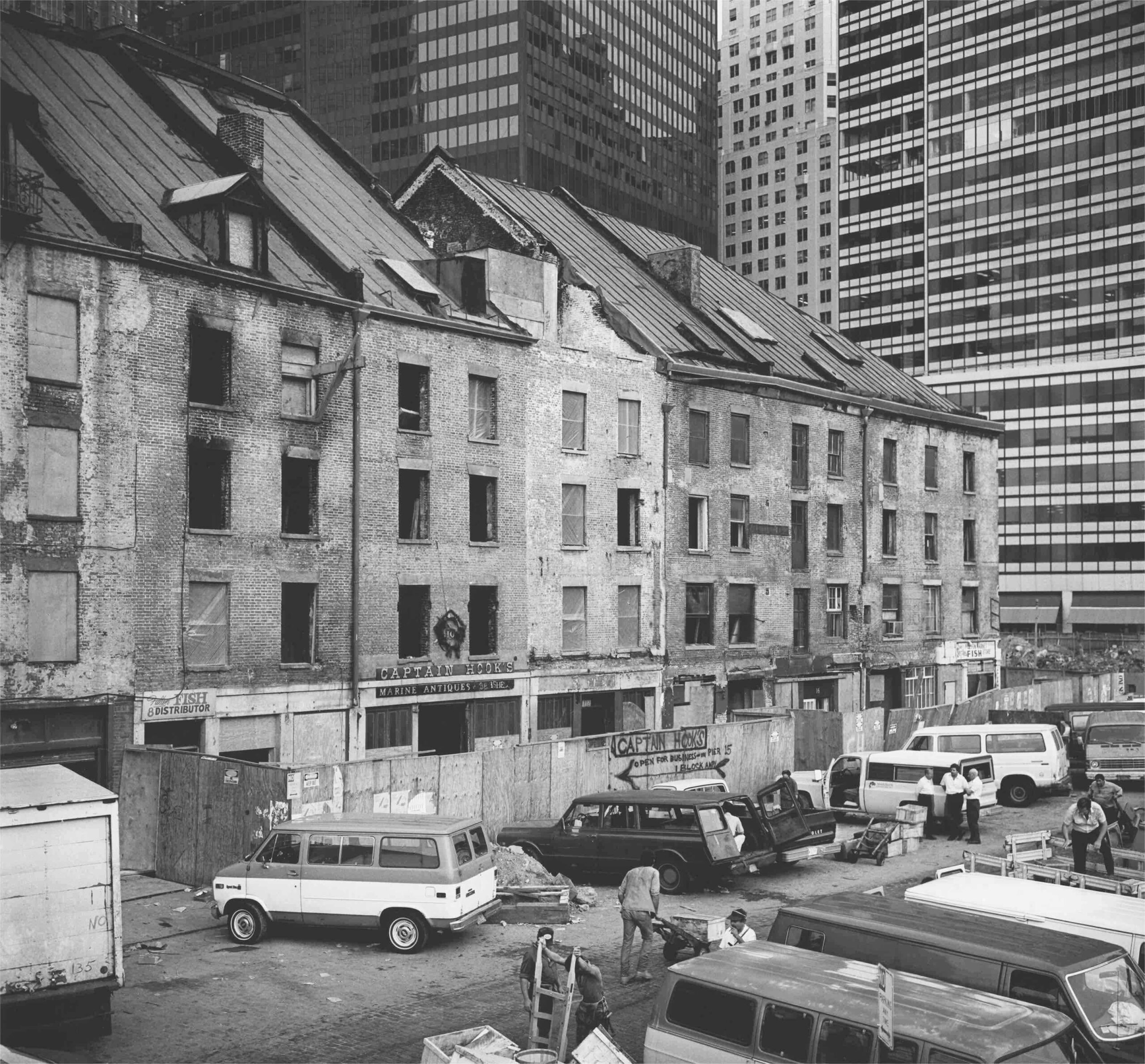

The northern stretch of the waterfront and upland blocks from Maiden Lane to Brooklyn Bridge, known generally as South Street Seaport, resisted development – in part from inertia and in part from active efforts of preservationists. In addition, Mob control over the Fulton Fish Market and the related businesses of the area persisted until the market finally relocated to the Bronx in 2005.

The Fulton Fish Market was home to a succession of markets and buildings since 1822. With its location on the wharves, the Fulton Market was ideal for unloading boats with their catch of fresh seafood. A market hall erected in 1869 was replaced in 1907 by the Tin Building (above), which still stands today. The reproduction of a 1936 vintage press photo shows the collapse of Pier 18 into the East River (below) and with it the 1909 Fulton Fish Market Building. It was replaced in 1939 under Mayor LaGuardia with the New Market Building, which also still stands today. That state-of-the-art structure modernized the market’s sanitation procedures. Although in the late 1950s, 85 percent of deliveries were made by refrigerated truck, the last trawler unloaded fish onto this pier in 1981, an event documented by Barbara Mensch’s photograph.

Barbara Mensch Photographs

While the ‘urban renewal’ of the west side of lower Manhattan added a whole new layer of land to the Hudson River shoreline in the form of Battery Park City, similar plans for the East River waterfront failed to move forward. By the mid-1990s, the area had a split personality. The southern end of Water Street had been developed with bulky superblock skyscrapers such as 1 New York Plaza (1969) and 55 Water Street (1972), at the time, the world’s largest privately-developed office building.

The northern stretch of the waterfront and upland blocks from Maiden Lane to Brooklyn Bridge, known generally as South Street Seaport, resisted development – in part from inertia and in part from active efforts of preservationists. In addition, Mob control over the Fulton Fish Market and the related businesses of the area persisted until the market finally relocated to the Bronx in 2005.

The Fulton Fish Market was home to a succession of markets and buildings since 1822. With its location on the wharves, the Fulton Market was ideal for unloading boats with their catch of fresh seafood. A market hall erected in 1869 was replaced in 1907 by the Tin Building (above), which still stands today. The reproduction of a 1936 vintage press photo shows the collapse of Pier 18 into the East River (below) and with it the 1909 Fulton Fish Market Building. It was replaced in 1939 under Mayor LaGuardia with the New Market Building, which also still stands today. That state-of-the-art structure modernized the market’s sanitation procedures. Although in the late 1950s, 85 percent of deliveries were made by refrigerated truck, the last trawler unloaded fish onto this pier in 1981, an event documented by Barbara Mensch’s photograph.

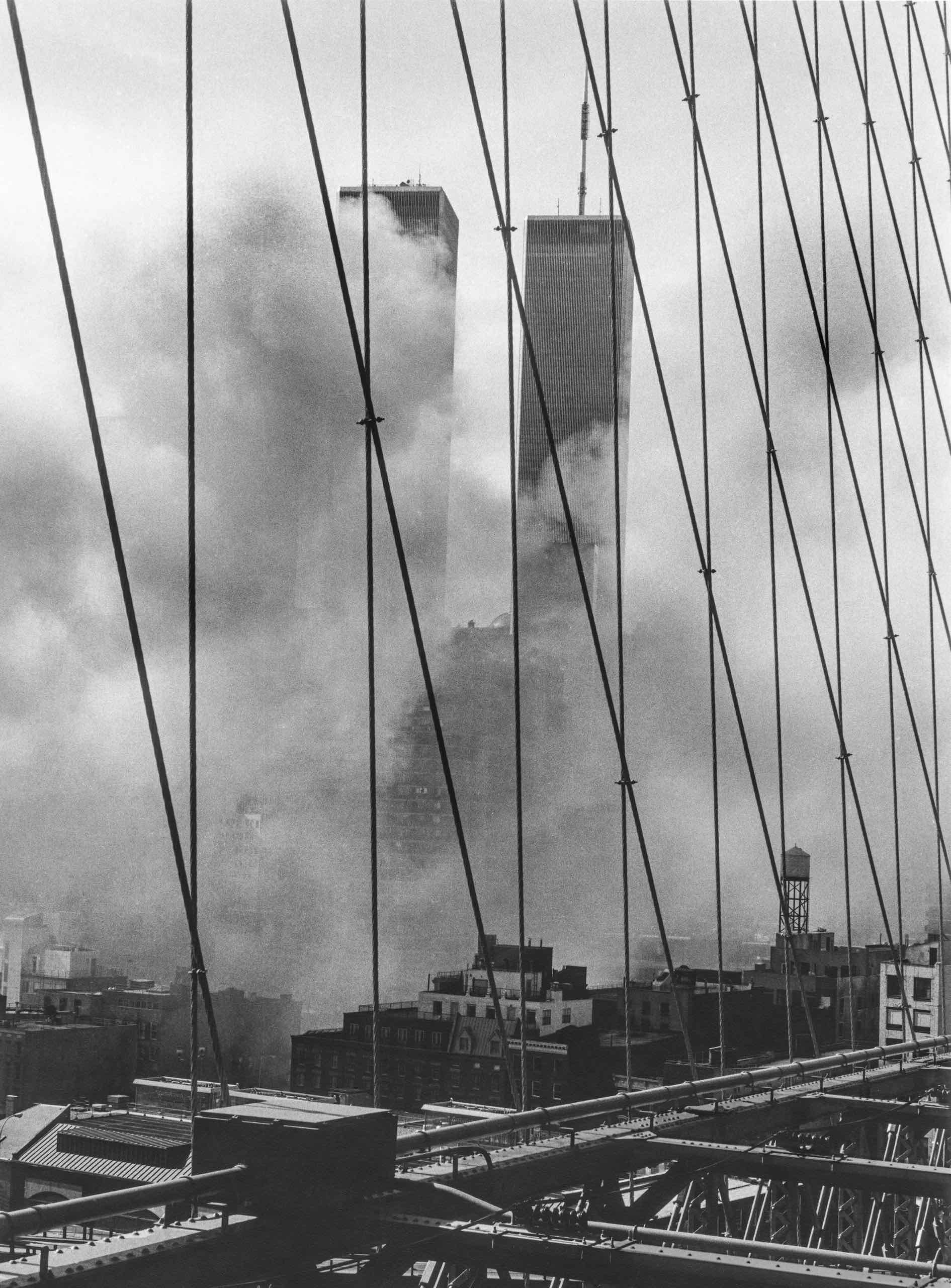

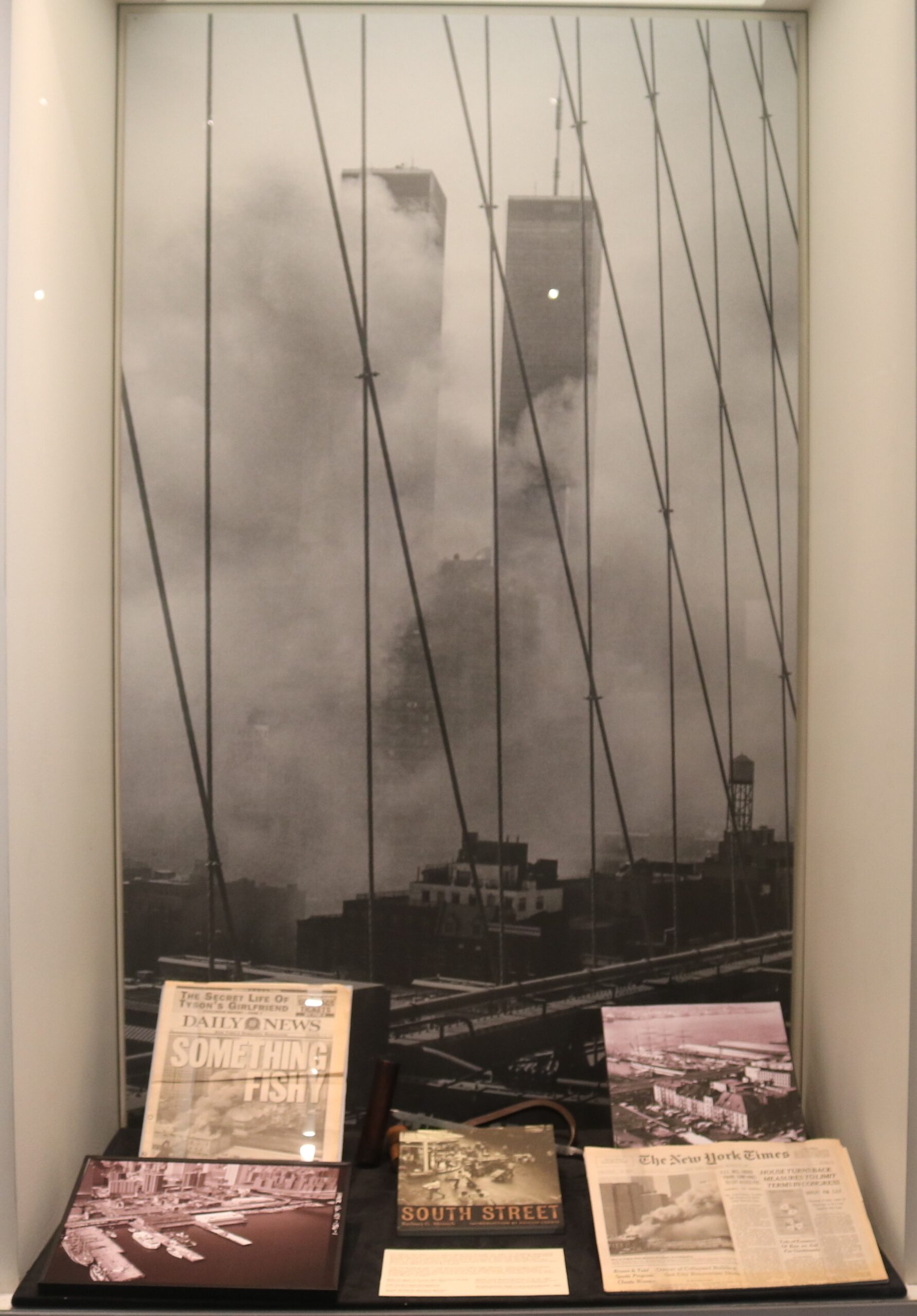

Fulton Fish Market Fire

On March 29,1995, a four-alarm blaze tore through the 1907 Tin Building, destroying the top two floors of the Fulton Fish Market’s oldest standing structure. Photographer Barbara Mensch captured the thick plumes of smoke obscuring the New York skyline. As the Daily News suggested in its headline, there was “Something Fishy” about the rapidly spreading fire, just days after the Giuliani Administration passed laws to counter Mob control of the market.

The Tin Building was a vital part of the Fulton Fish Market. Fishmongers unloaded seafood using hooks - such as those seen on display here. Barbara Mensch’s photographs, both on exhibit and in her book South Street, show the market’s inner-workings and its evolution during its final years. The market relocated to Hunts Point, in the Bronx, in 2005.

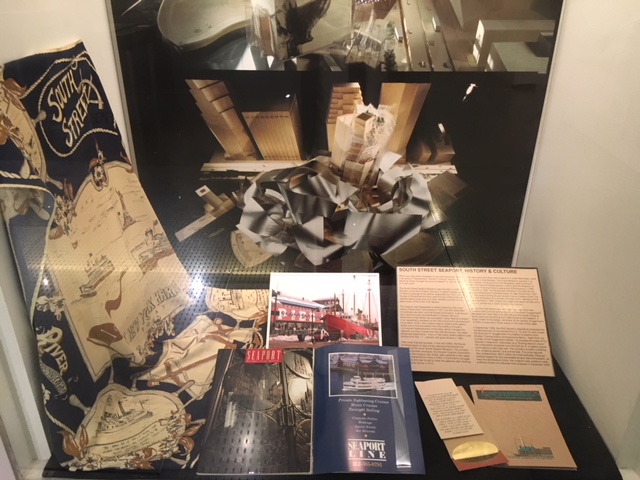

South Street Seaport, History & Culture

What new uses were necessary to reinvent Downtown for the 21st century? Residences? Tourism? Culture? Shopping? How would all these changes be accommodated? In new buildings, or in old ones?

The South Street Seaport Museum was founded in 1967 to tell the story of the Port of New York as a “museum without walls” in historic buildings of the district, especially the 1812 counting houses of Schermerhorn Row, and through a fleet of two tall-masted sailing ships and nine other vessels moored on the piers south of the Fulton Fish Market.

The Seaport was designated a historic district by the Land-marks Preservation Commission in 1977, but the restoration of buildings was slow until the Rouse Corporation, a developer who had previously revived Boston’s Faneuil Hall and Baltimore’s Inner Harbor as successful “urban festival markets.” In an agreement overseen by the City’s Economic Development Corporation (EDC), the museum was to receive both gallery space and a revenue stream from the profits of Rouse’s commercial redevelopment of the area, which included the restored counting houses and new infill structures. The retail shops and restaurants – many in the newly crated platform and structure for Pier 17 – opened with great fanfare in 1983.

After initial financial success, in the mid-1990s, the Rouse buildings began to lose money, leaving shipwrecked the finances of the South Street Seaport Museum. The complex was sold another developer, the Howard Hughes Corporation. Although the museum did, finally, open galleries in the upper floors of Schermerhorn Row in 2003, it continued to struggle financially and was forced to close the galleries after flooding by Hurricane Sandy in 2012.

Multiple plans for other new museums in lower Manhattan were conceived in the Nineties. The Police Museum opened in its first location on the ground of 25 Broadway (later moving to the First Precinct Headquarters in 2001) and the Museum of American Financial History opened at 26 Broadway in 1996. Founded in 1996, The Skyscraper Museum mounted its first pop-up exhibitions in donated space on Wall Street from 1997 to 2000 before finding its permanent home in Battery Park City. It joined the Museum of Jewish Heritage which opened its first building there in 1997. Plans for a nearby Museum of Women’s History, conceived in 2000, failed to be realized.

By far the most flamboyant and ambitious plan for a new museum and cultural facility was for a Downtown Guggenheim designed by Frank Gehry, to be built over the water bridging three piers and stretching from Wall Street to the Seaport. A huge model of the design, exhibited at the uptown Guggenheim in 2000, is pictured in three views on the rear of this case.

In September 1999, the EDC issued a request for proposals for the development of city-owned Piers 9, 13, and 14, and invited the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation to submit a bid. Director Thomas Krens commissioned Gehry – fresh from his triumph of the Guggenheim Bilbao – to surpass the scale of his Spanish masterwork. Described as a “floating titanium cloud,” the composition enclosed over 520,000 sq. ft. of gallery space, anchored by a 400’ high-rise. The complex included a skating rink, sculpture garden, and promenade. The price tag was also extraordinary: $670 million for a first estimate. Although political support for the improbable project was enthusiastic, as were the architecture critics, the museum was unable to raise sufficient funds and withdrew their proposal in December 2002.

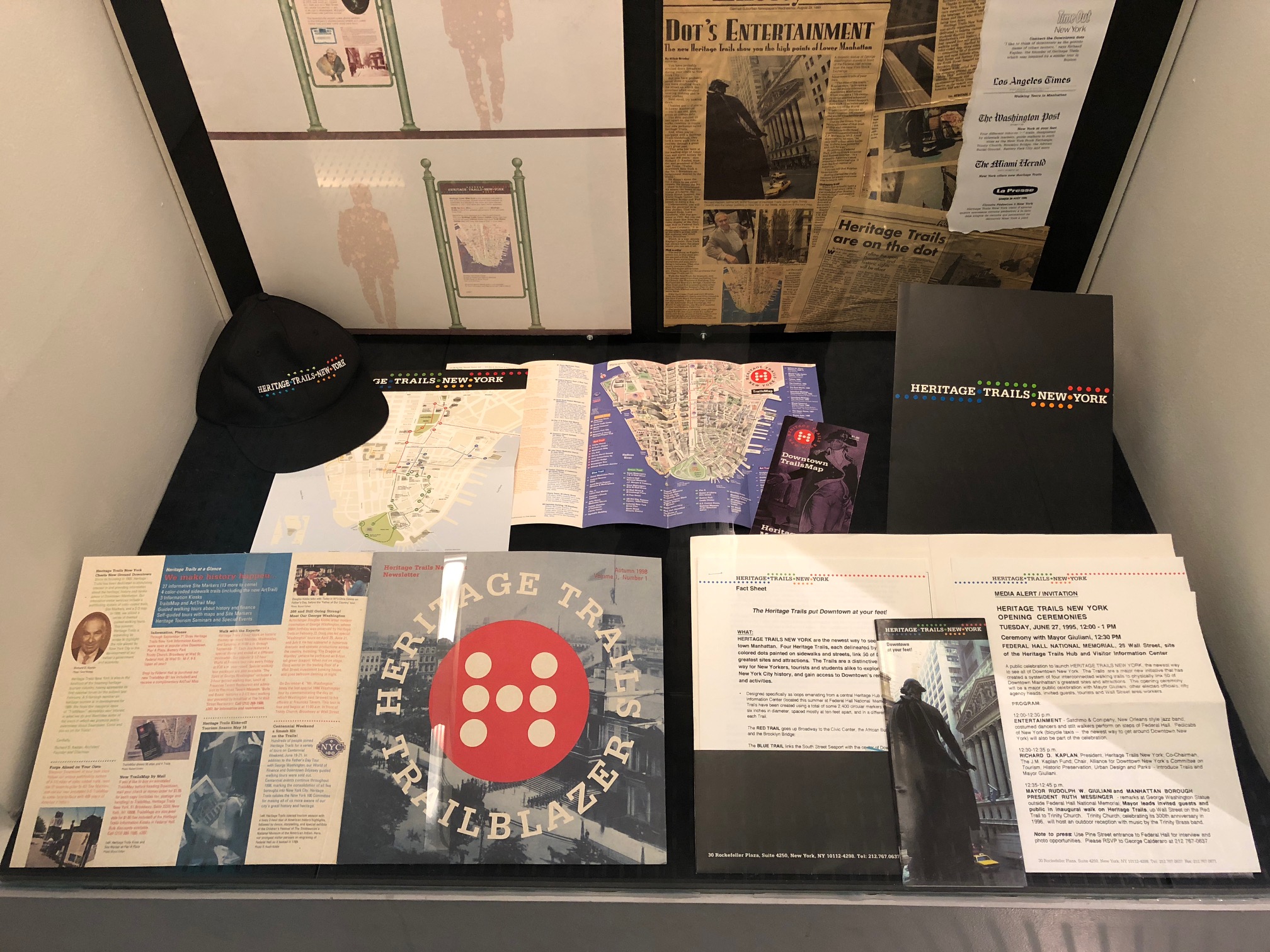

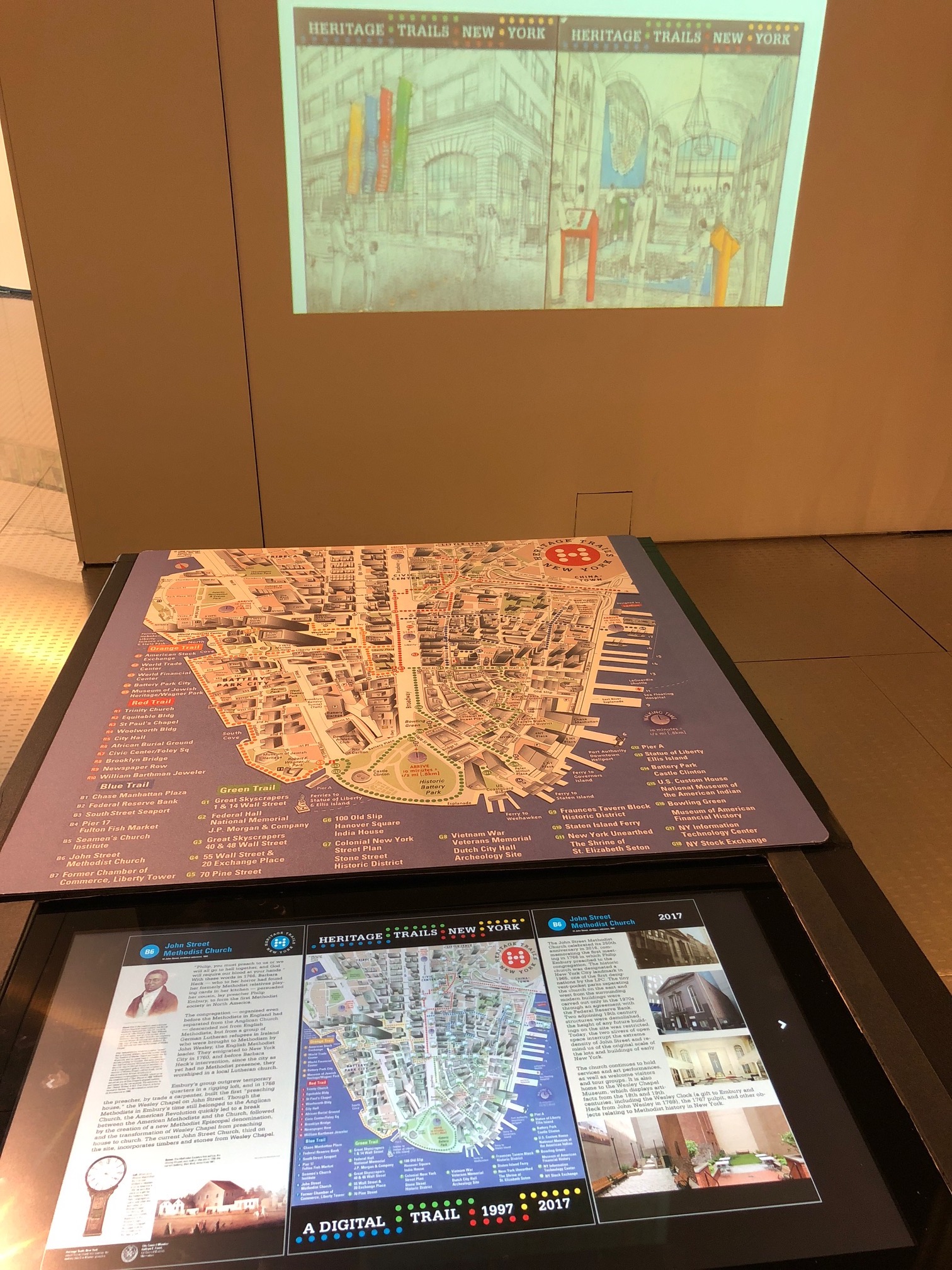

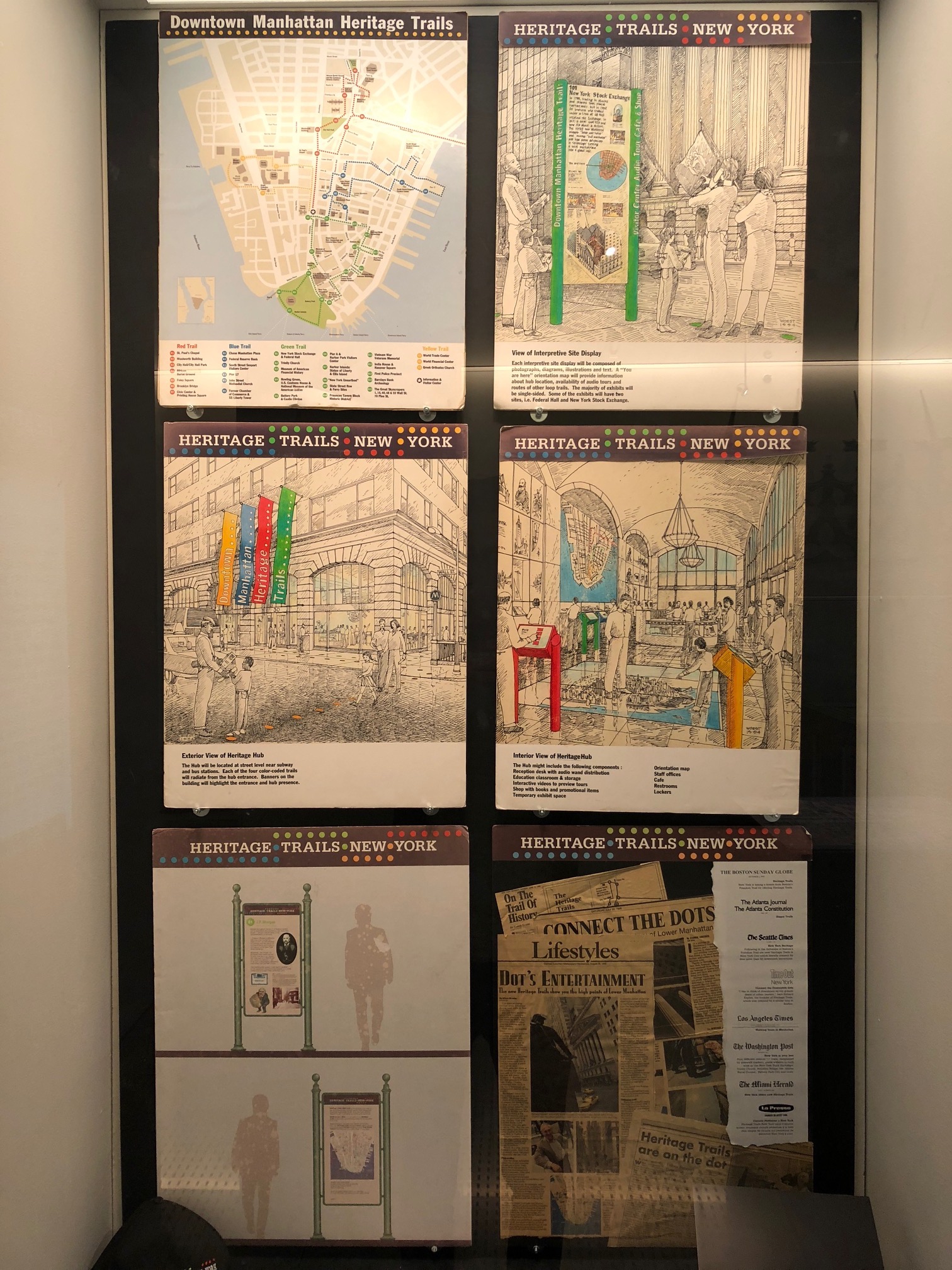

HERITAGE TRAILS NEW YORK

Heritage Trails New York, a public history project that created a network of tourist trails that looped through lower Manhattan debuted in 1995. Conceived by architect and philanthropist Richard D. Kaplan, four trails linked and illuminated Downtown's deep history, from discoveries of urban archeologists to stories of the great skyscrapers.

This case contains a selection of materials from the early years of Heritage Trails as its graphic identity was being developed by a team led by Keith Helmetag of the firm Chermayeff & Geismar. Boards used for presenting the project to potential supporters show preliminary ideas for stanchions, a visitor center, and wayfinding signs. The graphic design firm Chermayeff & Geismar also created an early version of the map and logos used across stationary and apparel. Later perspectival versions of the map were designed by Stephan Van Dam. An interactive 1998 map is viewable on the screen opposite, allowing visitors to browser the markers accessing the original (1997) or updated (2017) panels.