PRE-1850 HISTORY OF WALL STREET

Wall Street was not always the corner of capital: it had several earlier identities. This series of images pictures Wall Street from its colonial origins in the early 17th century through 1850, when its commercial character was set. The prints are a prequel to the identity of Wall Street as the storied financial district, recorded in the era before photography and before the invention of the elevator and steel-frame construction that would utterly change the architecture of the street and the skyline of New York.

DUTCH ORIGINS

First "discovered" by Henry Hudson in 1609, the island of Manhattan was explored for the States General of the Dutch Republic between 1611 and 1614 by private commercial companies, most notably the Dutch East India Company. Manhattan was chosen as the optimal location for a permanent settlement of the newly-formed Dutch West India Company, and in 1625, Fort Amsterdam was constructed at the southern tip of the island.

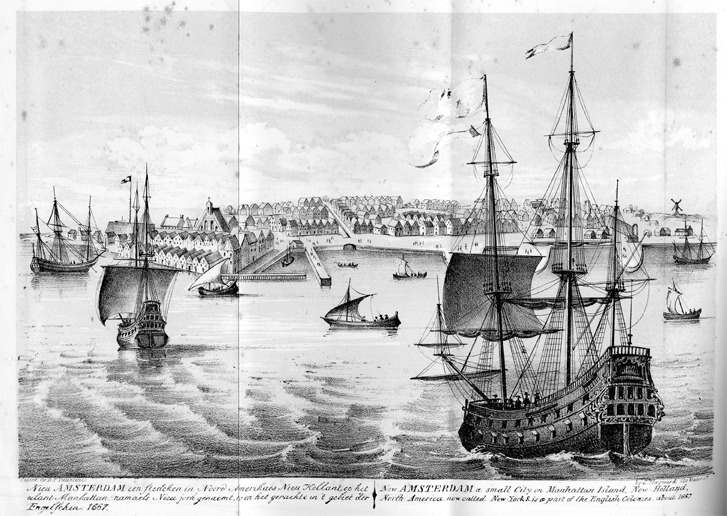

One of the earliest depictions of the Dutch colony, the top image was drawn by surveyor Cryn Fredericksz to show the investors in Amsterdam a vision for the town, rather than its actual layout. The topography of the area is inverted, due, perhaps, to the use of a camera obscura, showing the Fort on what seems to be the east side of the island. Native Americans appear in primitive long boats in contrast to the larger Dutch ships.

Drawn by the well-known 19th century lithographer George Hayward, the lower image shows New Amsterdam from the harbor in 1667, after British forces captured the island. Gabled rooflines cluster along the East River, with a windmill turning in the distance. Streaming inland is a canal that occupied modern Broad Street. A bastion of defense that would eventually become Wall Street can be seen towards the north edge of town at the right side of the image.

NEW AMSTERDAM: THE CASTELLO PLAN

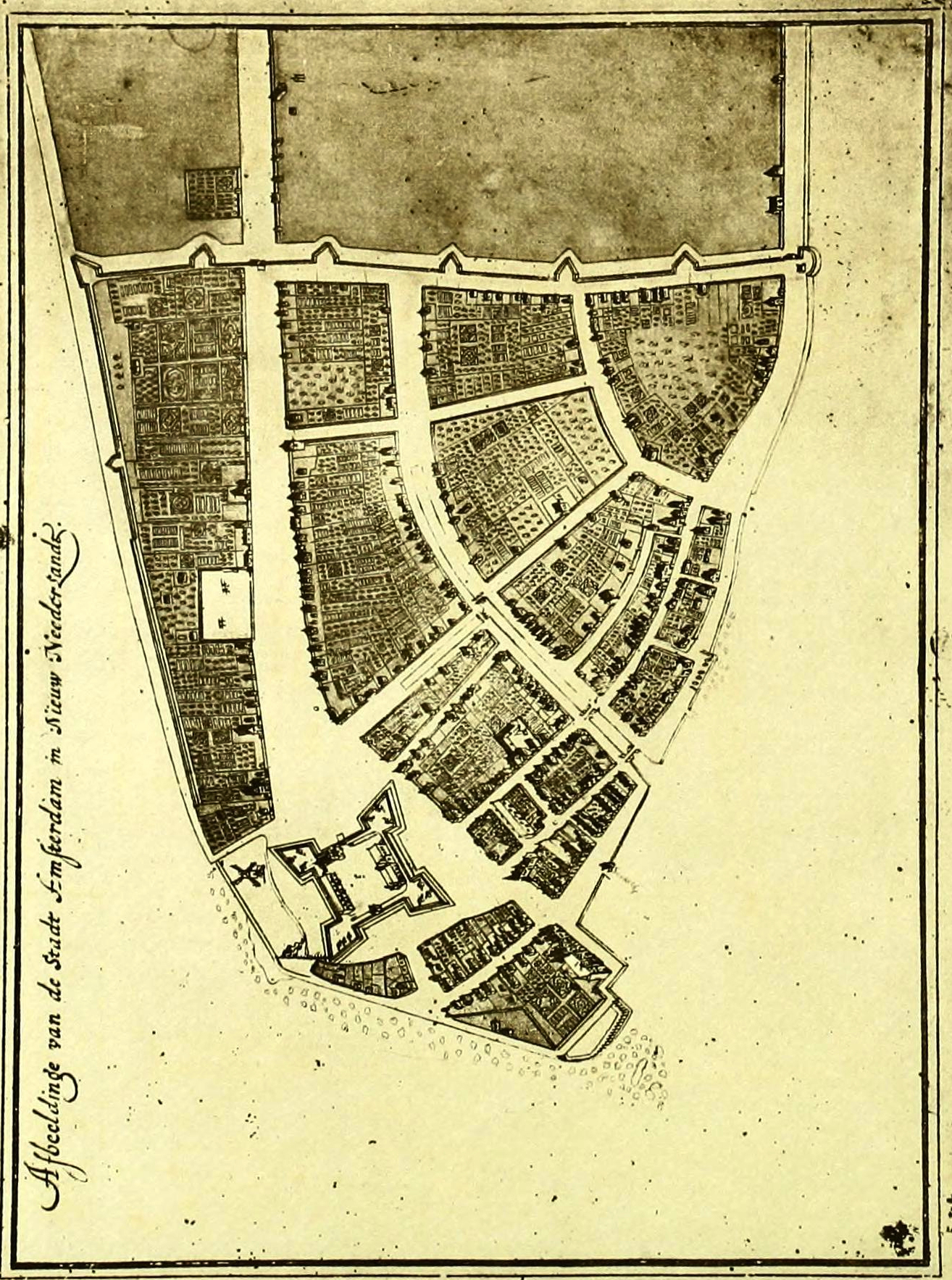

The Castello Plan is the most detailed map of New Amsterdam during the Dutch period, depicting the settlement in 1660. Copied many times through history, the original by the cartographer Jacques Cortelyou was commissioned by the burgomasters to send to the directors of the Dutch West India Company in Amsterdam. Open spaces of orchards and gardens featured prominently, as lot owners resisted building upon their property until land values rose. This posed a problem for the growing population of the settlement that had almost doubled to 1,500 inhabitants by the end of the 1650s. In response to the Cortelyou missive, the directors expressed discontent with the paucity of buildings in the small town, which they envisioned developing into a major port.

The map shows the settlement focused on the East River, with the large fort occupying the site that became Bowling Green, at the head of Broadway. The main canal, today's Broad Street, has a shorter offshoot to the west along present-day Beaver Street. At the eastern edge is Pearl Street, home to many handsome homes and warehouses of wealthy merchants. At the north end of the settlement is a nascent Wall Street, demarked by the protective wall. Colonial inhabitants of New Amsterdam feared invasion from New Englanders, but a treaty between the global powers kept them safe until 1664, when the British would capture the settlement and rename it New York.

BRITISH NEW YORK

In 1664, the British captured New Amsterdam and renamed it after the Duke of York. The Dutch ceded Manhattan for the island of Run in Indonesia and the legal possession of Suriname. During the Third Anglo-Dutch War in August 1673, the Dutch recaptured the city and renamed it New Orange, but the signing of the Treaty of Westminster in November 1674 returned the city to English rule.

This etching of New York, seen from across the East River, shows the city in 1717, when it was the third largest city in the British colonies; with a population of about 7,000, only Boston and Philadelphia were larger. The location of Wall Street is marked by the steeple of Trinity Church, the tallest spire on the skyline. No longer the northern end of the town, Wall Street had become the center of a bustling regional capital whose government met in the new City Hall (the domed building to the immediate right of Trinity Church). The many ships illustrate the city's active port. From 1717 to 1720 an average of 225 vessels used the port each year, trading goods primarily with Britain and the West Indies.

EARLY 18TH CENTURY

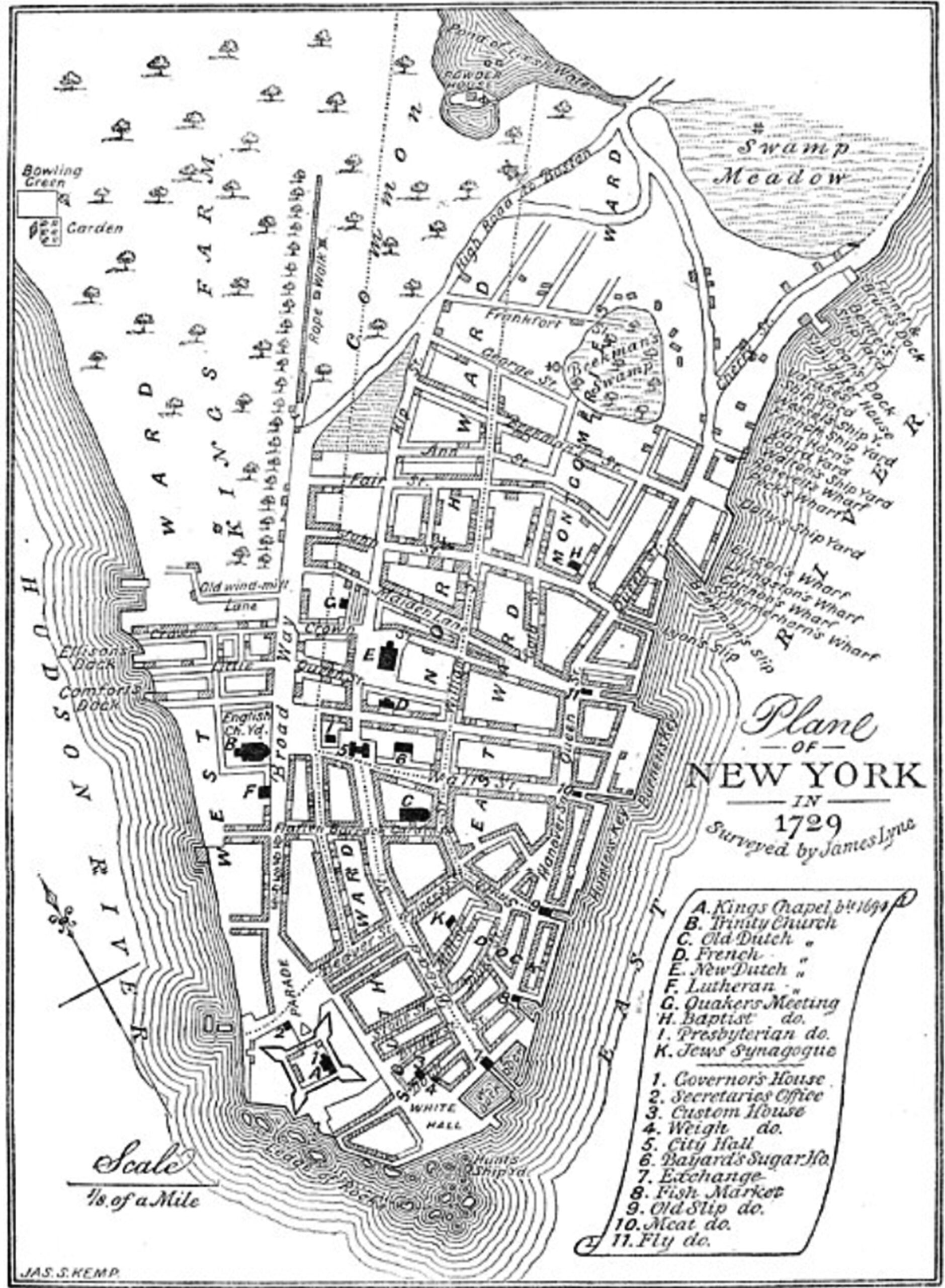

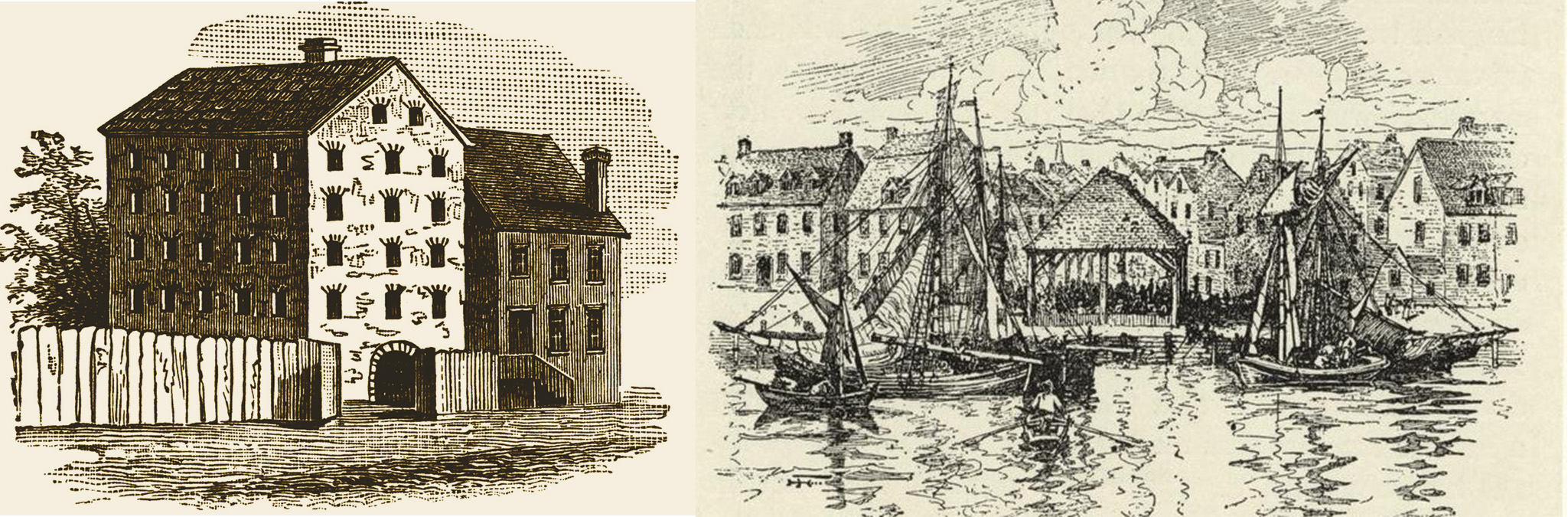

James Lyne's map of 1730* shows Wall Street's eclectic mix of development in the early 18th century. Four wholly dissimilar buildings stood between Broadway and William Street: the First Presbyterian Church, a tavern, City Hall, and Bayard's sugar house. One of the earliest major structures of the street, First Presbyterian Church was erected in 1719 on the north side between Broadway and Nassau Street and helped establish the new thoroughfare as a center of activity. The civic and social nature of the street continued with the tavern and with City Hall, constructed in 1703, then was interrupted by the sugar refining factory, which was built in 1730 on a large lot set back from Wall Street.

At five to seven stories, sugar houses were taller and more monumental than most contemporary buildings. The massive brick and stone structures with deep windows marked an intermediate stage between home factories of the 17th century and immense modern plants of the 19th century. Sugar has been an important commodity and industry in New York from colonial times, shipped and stored along the East River and managed from Lower Manhattan offices. The Bayard sugar house was located about halfway between William Street and City Hall as noted on the map at No. 6; today the seventy-story tower 40 Wall Street occupies the site. Sugar houses were considered large imposing eye-sores in contemporary days, which was especially true of the Wall Street sugar house, as it stood in such stark contrast with the neighboring civic buildings.

THE SLAVE MARKET

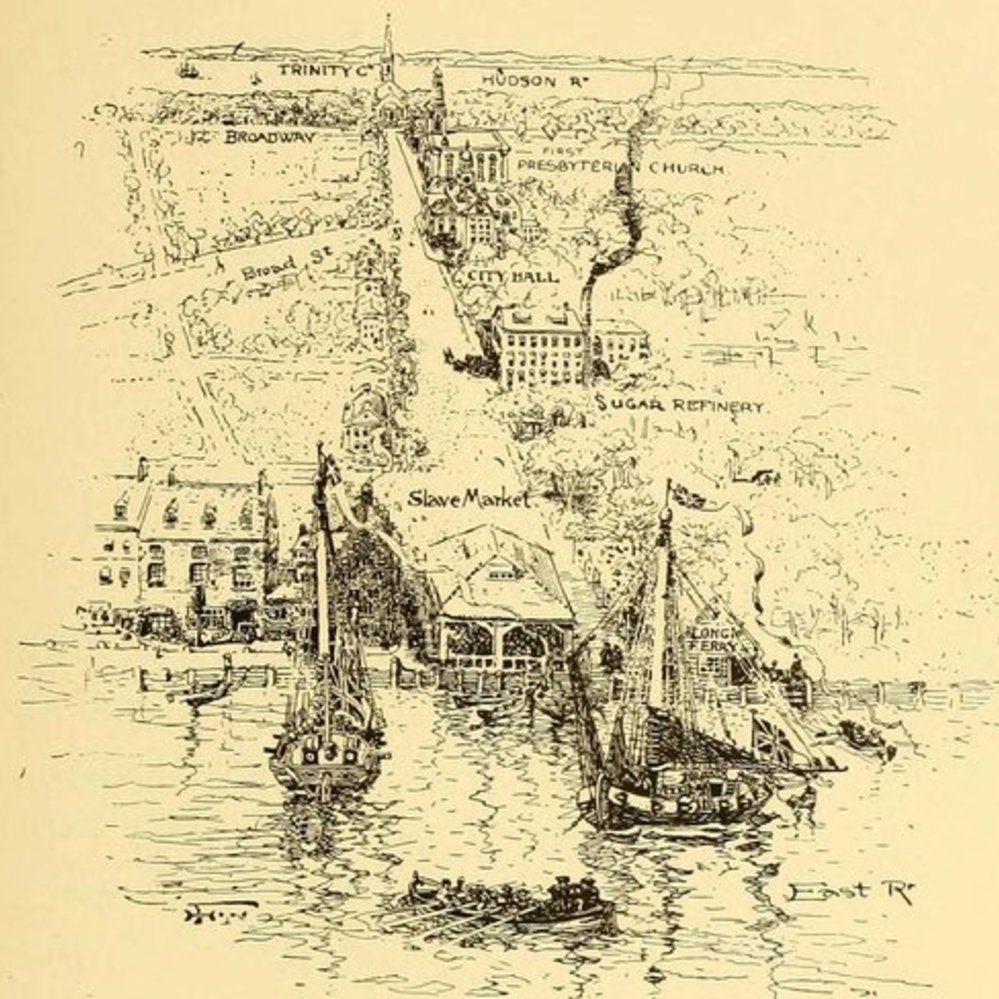

This 1908 artist's view of Wall Street in 1735 portrays the length of the street and the mixture of uses in the century before it took on its financial character. Most development was clustered towards the East River and its bustling port activity. Visible at the water's edge is a simple peaked-roof structure, the Slave Market, located at the present-day intersection of Wall and Water Streets, that served as the site for the hiring, buying, and selling of slaves.

In the early 18th century, slavery was an important source of New York City's labor force, with 40 percent of white households owning slaves. Continued trade with the West Indies and Britain ensured a growing population of slaves, who were often bought by a ship workers. Slaves would be sent into the streets to find day work, which soon began to spur anxieties among the upper classes. In 1711, a slave market was established at the foot of Wall Street. In 1726, an ordinance was passed declaring the Market House at Clark's Slip the sole public market place for the sale of corn, grain, and meal; from this point, the site was known as the Meal Market, although slaves continued to be bought and sold there. By the mid-1700s, the conditions of lower Wall Street were improving, largely due to the Merchants Coffee House where wealthy merchants often met. These businessmen saw the Meal Market as an obstruction to the agreeable prospects of the East River end of Wall Street and successfully petitioned for its removal. In February 1762 the Meal (Slave) Market was dismantled.

CITY HALL

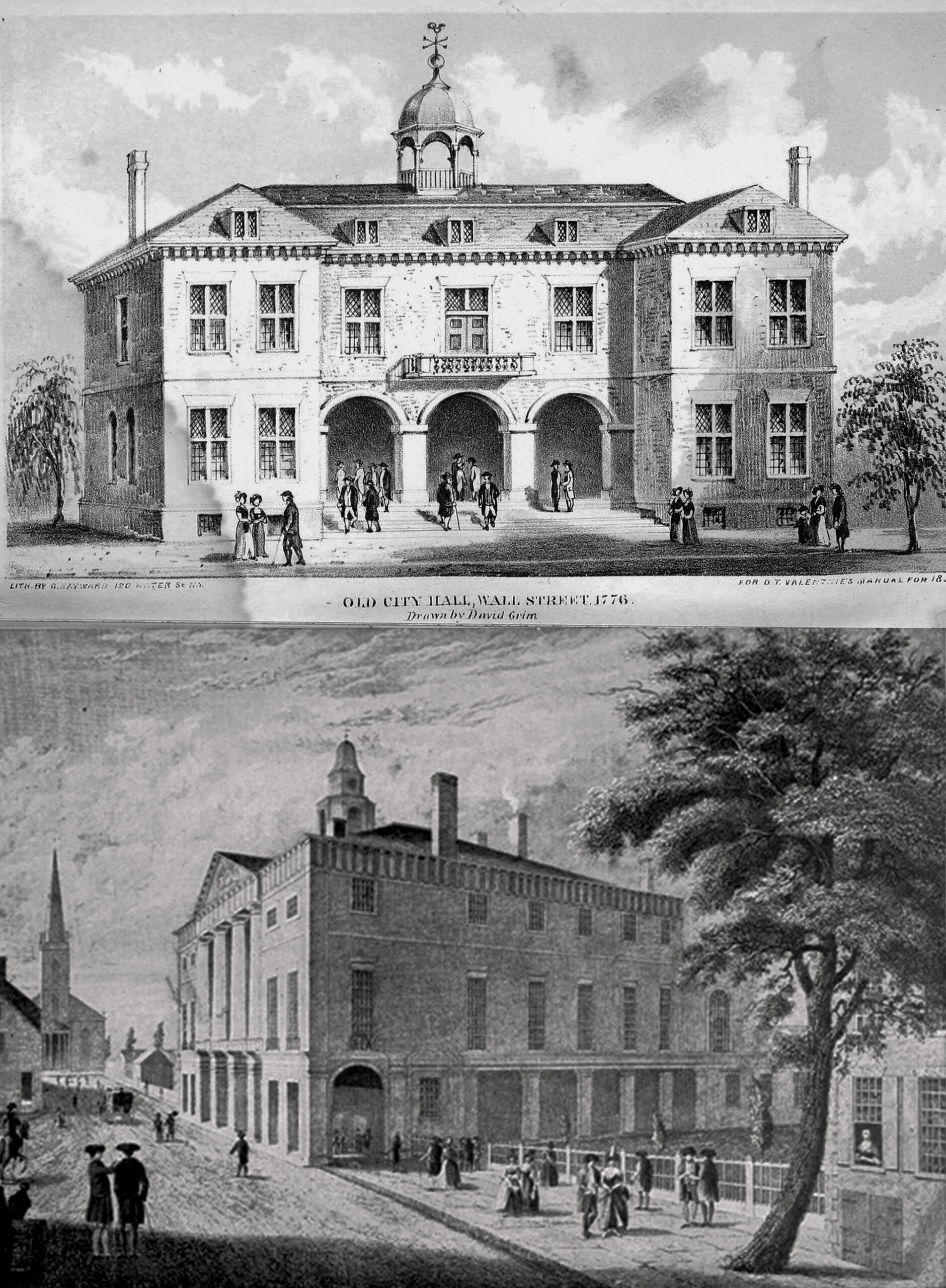

City government in New Amsterdam had met in the Dutch Stadt Huys, built as a tavern in 1642 on Pearl Street, then known simply as The Waterside. After the British takeover, in 1703, a new building, seen in the upper image, was constructed to serve as City Hall. Together with Trinity Church and the First Presbyterian Church, City Hall gave weight to the dignity of the west end of Wall Street.

After the Revolutionary War, in 1788, Pierre L'Enfant, who was best known for his later planning of the new capital city of Washington D.C., designed the renovation and enlargement of City Hall, which became knows as Federal Hall when it housed the Continental Congress. The balcony served as the location of the inauguration of George Washington as the nation's first president on April 30th, 1789. The nation's capital moved to another temporary home in Philadelphia in 1790 and the building resumed its previous function of city hall until the current City Hall was constructed in 1812.

EAST RIVER COMMERCE

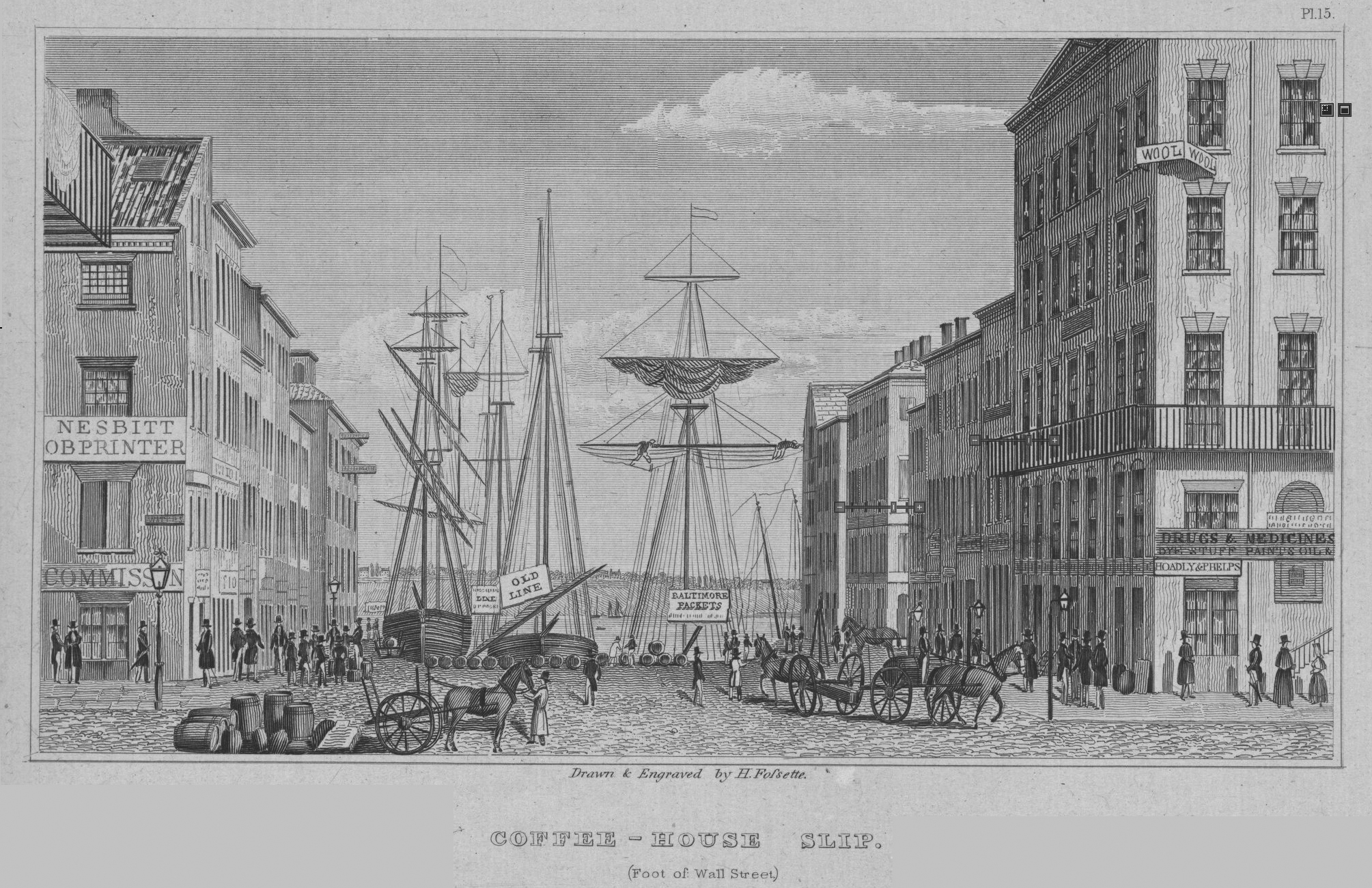

Wall Street began its commercial and financial development along the East River where port activity was focused. At the end of the 18th century docks lined Front Street, then the water's edge, and commodities of all kinds were unloaded to warehouses, while merchants traded the value of shipments on exchanges. The goods arriving to New York in the 1790s were registered at the coffee houses on Wall Street and included coffee, tea, sugar and molasses, fine furniture, cloth, cotton, and enslaved men, women, and children. The custom of drinking coffee had been introduced during the Dutch Period, but it was after the English take over of New York, the British manners of tea and coffee drinking became a social activity. Coupled with the need for public assembly spaces where news could be shared, coffee houses soon became centers of the business and political life of the city.

The Tontine Coffee House was organized by a group of 24 prominent brokers and merchants who had entered into an exclusive trade agreement on a common-commission basis, creating the Tontine Association. Rivaling the older Merchants Coffee House located diagonally on the southeast corner of Wall and Water streets, the Tontine became the premiere meeting place for New York's wealthy merchants after a fire destroyed the Merchants Coffee House in 1804. The New York Stock Exchange traces its origins to the Tontine, where early trading of the New York Stock & Exchange Board took place until relocation to the moved Merchants Exchange at 55 Wall Street in 1817.

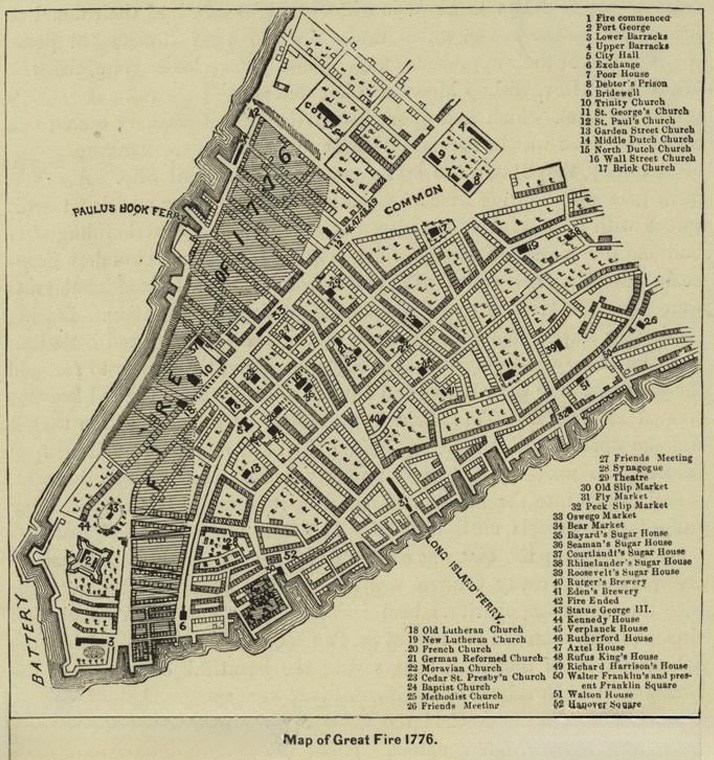

FIRE OF 1776

New York was the only American city to remain under British military occupation for nearly the entire Revolutionary War, and it suffered more physical damage than any other city. In late 1776, the American troops under General Washington fought a series of battles in Brooklyn and Manhattan, and by the end of summer, they were dispirited and in danger of being surrounded. On September 12, Washington accepted the advice of his officers to abandon the city. The British occupied Manhattan for the remainder of the war, holding patriot prisoners of war in appalling conditions in the Bayard Sugar House on Wall Street.

Just after midnight on September 21, a fire broke out in the Fighting Cocks Tavern on Whitehall Street and quickly spread uptown and by 2 a.m. had consumed Trinity Church. By the time the fire burned out around midmorning, more than 500 houses, one quarter of the city's total, were destroyed. The British were quick to suspect arson and rounded up about two hundred men and women for questioning, including a young captain named Nathan Hale, who admitted to being an American spy and was hanged the next morning. The housing shortage produced by the fire, and another in 1778, caused a number of churches, including the First Presbyterian Church on Wall Street, to be commandeered for barracks, prisons, or storehouses. Large shantytowns filled the burned-out areas, and rebuilding did not begin in earnest until after the war ended.

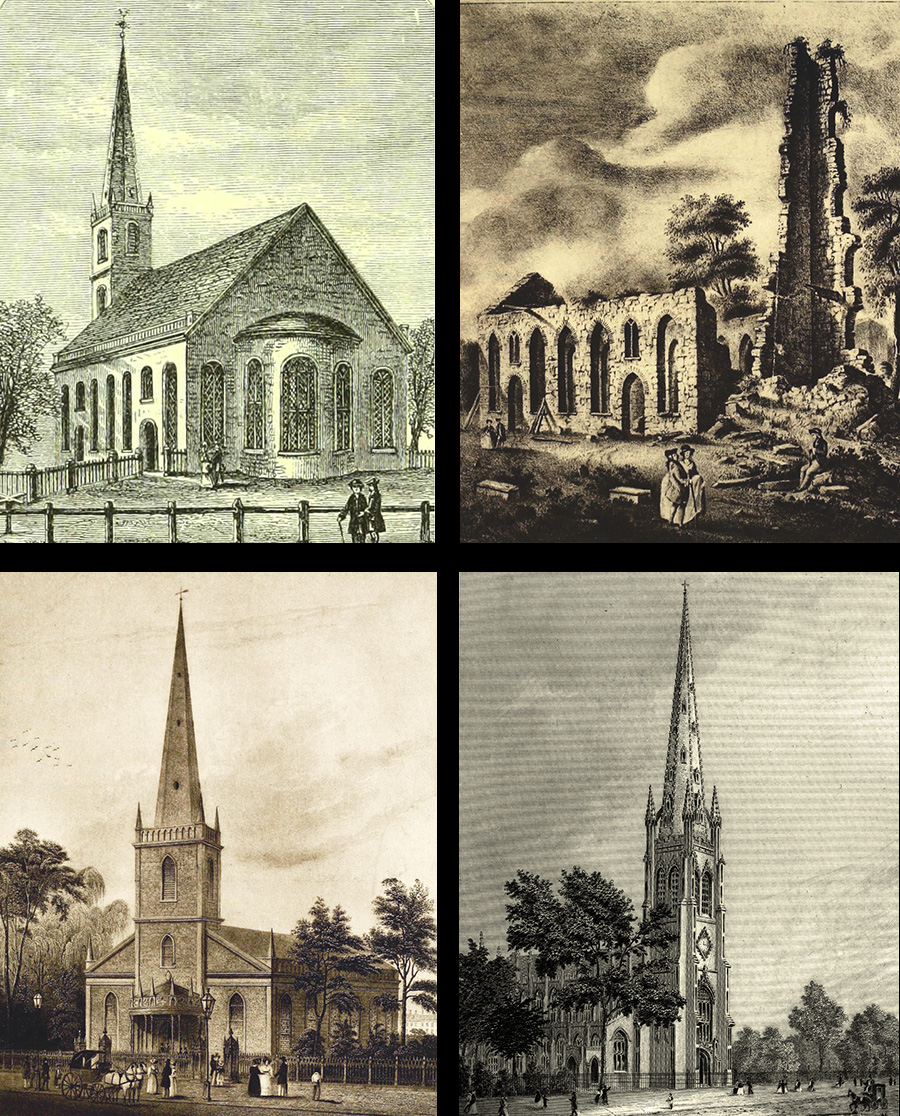

Top Left: Martha J. Lamb, History of the City of New York: its origin, rise and progress, Volume 2, 1877, pg. 572. Retrieved from www.archive.org. Top Right: Percy Rivington Pyne, The Notable Percy R. Pyne 2D. Collection, 1912. PL 212. Bottom Left: I. N. Phelps Stokes, The Iconography of Manhattan Island, PL122. Retrieved from www.archive.org. Bottom Right: Image courtesy of the NYPL.

TRINITY CHURCHES

Trinity Church has anchored the head of Wall Street for more than 300 years. Completed in 1846, today's Trinity is the third church built on the site. The first, seen in the top left image, was granted a charter in 1697 by King George III and held its first service in 1698. It was a modest rectangular structure with a small porch and a steeple that faced the Hudson River, away from Broadway and Wall Street. This first Trinity burned in the great fire of 1776, leaving a ruined pile that was demolished and rebuilt as the second Trinity in 1790. Seen in the bottom left image, the new church was oriented with its entrance and steeple towards Wall Street. This simple building lasted only fifty years before a heavy snowfall in the winter of 1838-39 damaged the roof byond repair, and it was demolished.

The current 19th-century edifice by architect Richard Upjohn is considered a classic of Gothic Revival architecture. Faced in brownstone, the new Trinity Church featured a 281-foot (86 m) bell tower that was the tallest building in the city until 1890 when the World Building rose 310 above City Hall Park and launched the rise of the commercial skyline. Trinity Churchyard, the adjacent cemetery at Wall Street and Broadway, opened in1697, and is the final resting place of many historical personages such as Alexander Hamilton. Preserving valuable open space in the highly developed financial district, the cemetery and the church are listed in the National Register of Historic Places, and the church was recognized as a National Historic Landmark in 1976.

MANSIONS AND BANKS

In the late 18th and early 19th century, the blocks between City Hall/ Federal Hall and the active commerce of the East River port filled in with a continuous row of handsome residential buildings. With the seat of the federal government located in Pierre L'Enfant's newly expanded Federal Hall, the area became the center of political activity and a highly coveted address for government functionaries, foreign dignitaries, civic leaders, and businessmen. The city's elite paraded past elegant dwellings and the imposing public edifices that made Wall Street a magnet of high society.

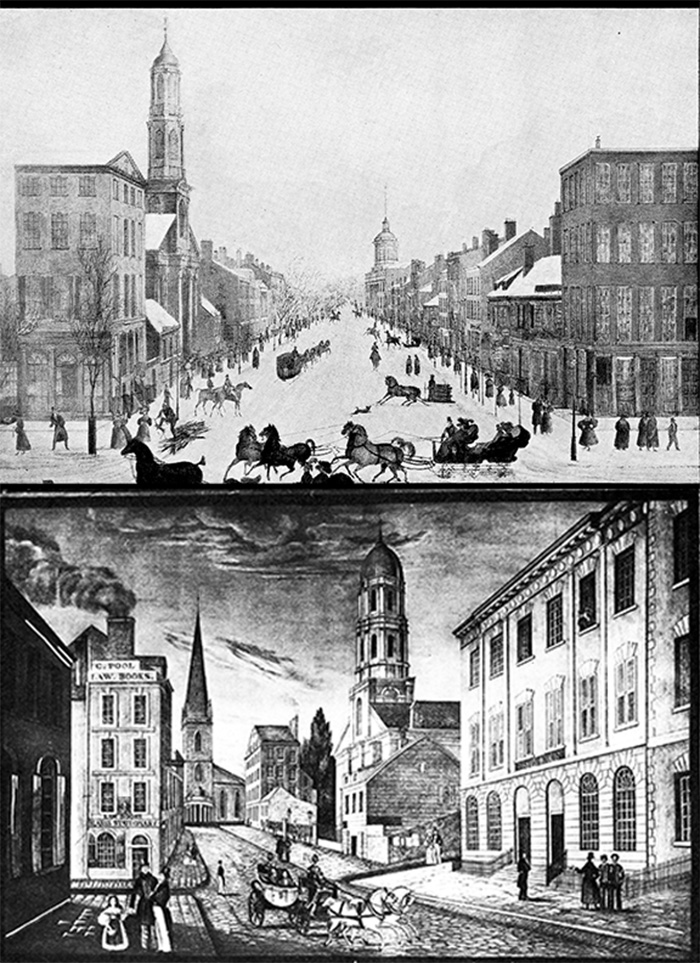

Mansions soon gave way to the commercial impulses of the street, though, even as the outward residential architecture persisted for a brief period. The first bank established in the city, as well as the first to locate on Wall Street, was the Bank of New York, which was organized in 1784 and moved to the northeast corner of William Street in 1797 (in the building at the left of the lower image). Adjoining it to the east (right), was the New York Insurance Company, which operated from the residence of the company's president Charles McEvers.

With the monumental presence of the new Merchants' Exchange, designed by Martin E. Thompson and completed in 1827 (its raised dome is visible in the image above), Wall Street began its first transformation into a corridor of purpose-built bank buildings. The first generation of the dominant style of Greek Revival temples and treasuries included Thompson's 1824 Branch Bank of the United States and the Phenix Bank at 45 Wall, visible at the right of the foreground.

WALL STREET IN 1825

This early 19th century view of Wall Street shows a mix of building heights and types. It was made by Peter Maverick (1780-1831), an eminent engraver and painter who worked chiefly for book-publishers and bank-note companies. The image shows Wall Street before the Great Fire of 1835. This snowy scene of horse-drawn sleighs running north on Broadway in front of Trinity Church depicts many notable buildings including the First Presbyterian Church (the steeple on the left hand side) which was used as a hospital during the Revolutionary War and was subsequently moved to Fifth Avenue near 12th street in the 1840s following the Great Fire. Further down the street is the domed Merchant's Exchange. Lower image is titled "Wall Street. 1825 Broad Street, including the Custom House, to Trinity Church." On the north, at the Nassau Street corner, appears the First Presbyterian Church with only one small structure between it and the large building on the Broadway corner. On the south, at the Broad Street corner: "C. Pool | Law Books" and "Law Books | Blanss

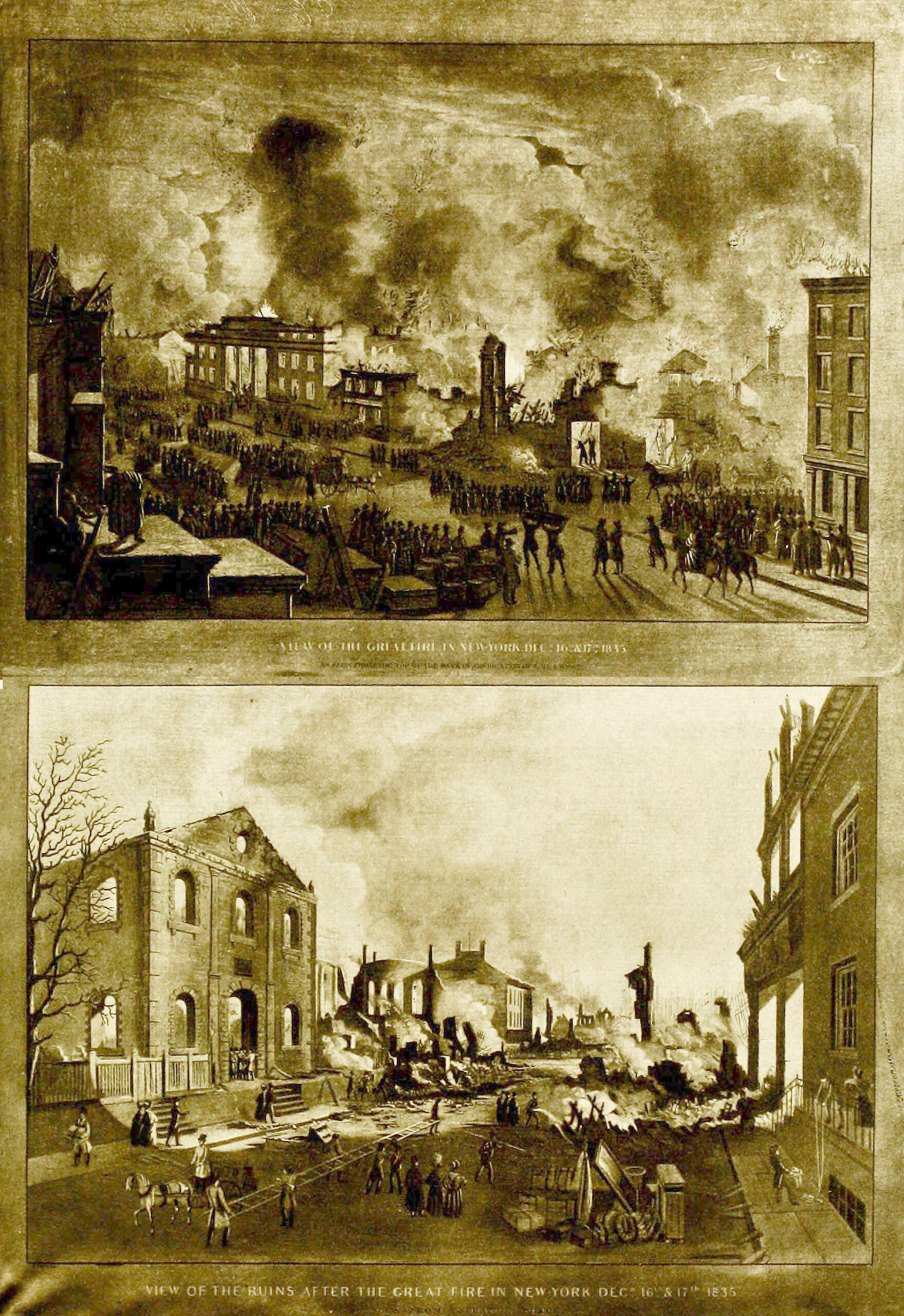

THE GREAT FIRE OF 1835

On the frigid evening of December 16th, 1835, a fire erupted in a warehouse at the corner of Exchange and Pearl streets. The conflagration consumed around 650 buildings, and within an hour included the entire south side of the Wall Street to Broad Street. The opulent Merchant's Exchange, completed just twelve years earlier, caught fire around three in the morning, and its great dome collapsed a half hour later. The fire was finally brought under control when firefighters brought gunpowder from the Brooklyn Navy Yard to the base of Wall Street and created a firebreak. Two days later, an eyewitness account published in The Herald conveyed the devastation:

"On going down Wall street, I found it difficult to get through the crowd. The hose of the fire engines was run along the street and frozen. The front blocks of houses between Exchange Place and Pearl street, on Wall, was standing, behind which were all ruin and desolation. At the corner of Wall and Pearl, on looking southwardly, I saw a single ruin standing about half way to Hanover Square. I proceeded, climbing over the hot bricks, on the site, as I thought, of Pearl street, (but of that I am not sure) till I got to the single solitary wall that reared its head as if it was in mockery of the elemental war. On approaching, I read on the mutilated granite wall, "ARTH- TAP-N, 122 PE-L STREET." These were all the characters I could distinguish on the column. Two stories of this great wall were standing-the rest entirely in ruins. It was the only portion of a wall standing from the corner of Wall street to Hanover Square-for beyond that these are nothing but smoke, and fire, and dust."

CUSTOMS HOUSE & MERCHANTS EXCHANGE

With the removal of the federal government to Philadelphia in 1790, Federal Hall returned to housing the municipal government until 1812, when the current City Hall on Park Row was completed. The old Wall Street structure was razed and commercial buildings occupied the site until 1833, when construction began on the U.S. Custom House, the present-day Federal Hall National Memorial. The building remains one of the great landmarks of 19th-century American architecture.

From its establishment in 1789, the U. S. Customs Service levied taxes on imports and ship tonnage and was the major source of federal revenue until the establishment of personal income tax in 1913. Completed in 1842, the new Custom House was an imposing Doric temple, an American Parthenon, set atop a tall base and flight of granite steps designed by architects Ithiel Town and Alexander Jackson Davis. While the exterior has remained unchanged, save for the addition of a statue of George Washington in 1882, the interior has experienced many remodelings. Operated as the Customs House until 1862, the building served as one of six U. S. Sub-Treasury locations until 1920 and held millions of dollars of in gold and silver in its vaults. In 1939, it was designated a National Historic Site, and today it operates as a museum under the National Parks Service.

Another treasure of American classicism is the second Merchant's Exchange at 55 Wall Street, built to replace the first exchange which had been destroyed in the Great Fire of 1835. Completed in 1846, the design by architect Isaiah Rogers boasted a colonnade of a dozen colossal Ionic columns that disguised the three stories within and the central domed rotunda. Occupying the entire block on the south side of Wall Street between William and Hanover streets, the exchange served as the major venue for buying and selling commodities, the offices of many prominent shippers, merchants, auctioneers, and brokers, as well as the meeting place of the precursor to the New York Stock Exchange. The Customs Service relocated to the building in 1862, and an expansion in 1901-10 by McKim, Mead & White for the National City Bank added the second colonnade to the facade and a grand banking hall.

In 1862, the Customs Service relocated to 55 Wall, occupying it until the end of the century when the building was sold to National City Bank, which commissioned architects McKim, Mead & White to expand the building and redesign the interior. The architects doubled the height of the building, adding four stories within and an upper colonnade of Corinthian columns on Wall Street, and created a spacious cruciform banking hall.

A STREET OF BANKS

An iconic view of Wall Street in the 1850s looking west towards Broadway and the towering steeple of Richard Upjohn's 1846 Trinity Church. The image clearly reflects a scene much changed from half a century before, with commercial buildings of an immense magnitude splitting and conquering the blocks of Wall Street. In fact, following the Great Fire of 1835, most of lower Manhattan east of Broadway was rapidly replacing residential buildings for commercial buildings, in the classical architectural styles of Greek and Roman temples as seen in this picture. The Great Fire of 1835 had allowed a proper and orderly design of buildings and straightening and widening of streets in lower Manhattan that always seemed to wrestle with the rest of the island's grid system. Following the fire, almost all the houses on Wall Street and Broad Street were demolished by 1842, with the only family living on Wall Street occupying a space above a bank. Similarly, every house on Pine Street was demolished. On Pearl Street, every number above 57 was home to a commercial building. All in all, the area became densely packed with commercial buildings. The phrase, "Financial District," was epitomized by Wall Street in the 1850s, which was the densest of these commercial streets.

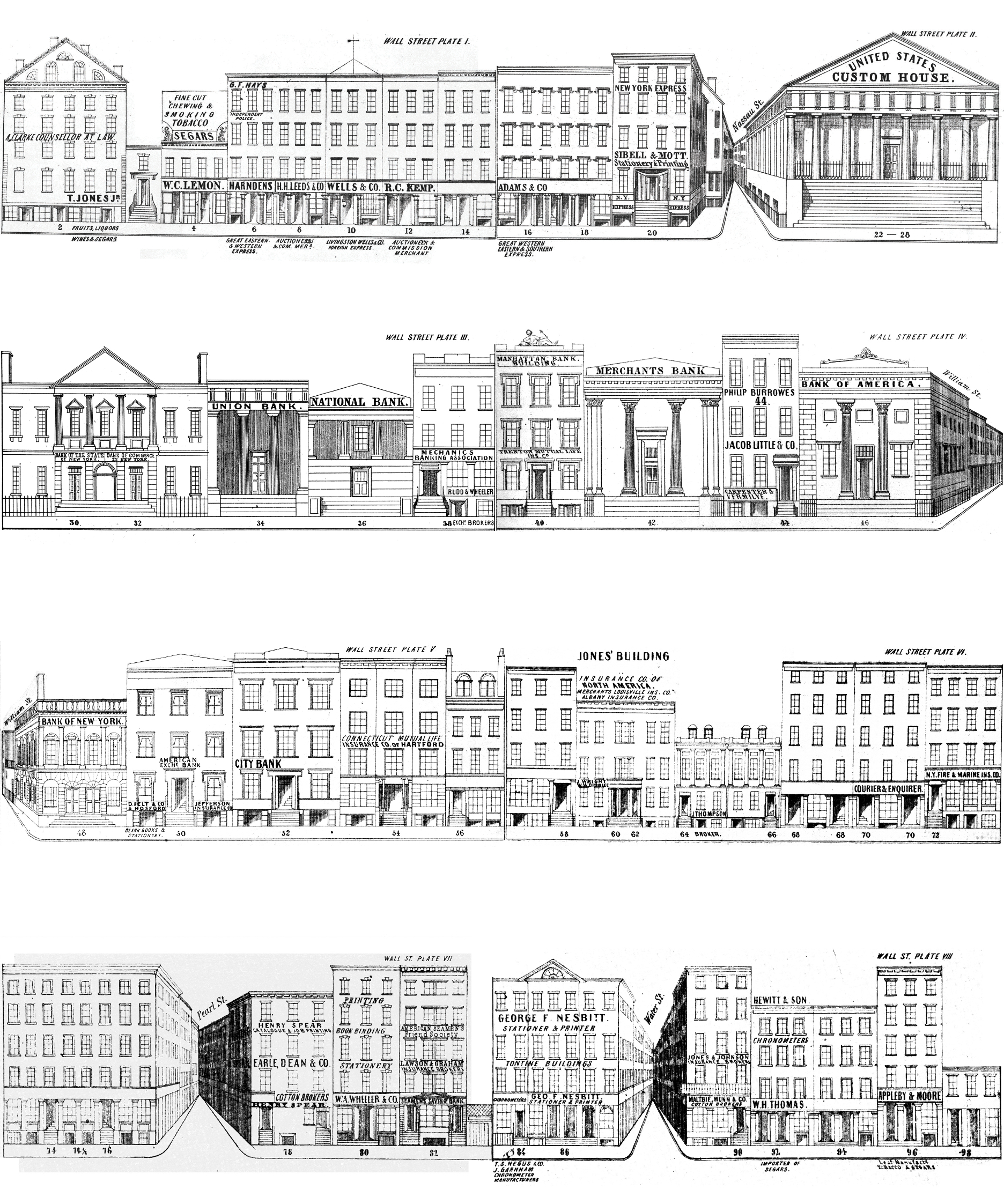

LOWENSTROM'S PANORAMA-1850 SOUTH SIDE

The images used to make this panoramic view of Wall Street come from a book published in 1849 called the New-York Pictorial Business Directory of Wall-St. Located in part at the New York Public Library's rare-book archives, the Directory contained complete views of all the buildings on Wall Street. The Directory's pages featured real-estate listings, notices, and advertisements proper to the buildings' occupants, owners, and associates.

The Directory offered a list of businesses on Wall Street and served as an important resource for the business community. Rather than being explicitly about the architecture of the buildings themselves, these simple line drawings diagram the businesses located in each building- they match a company (or companies) to an address. Business directories such as these, in conjunction with tourist atlases constitute an important resource for picturing Wall Street in the middle of the 19th C.

The American trade in lithography grew significantly in the early to mid 19th C. as those trained in Europe began to set up practices in major cities in the United States. The images here were engraved by Francis Michelin whose firm Sharp, William, Michelin, Francis & Co. produced a number of prints in the 1840s that survived and are still in circulation today.

LOWENSTROM'S PANORAMA-1850 NORTH SIDE

In the first frame, we move east (left to right) along Wall Street viewing the buildings on the north side of the street. The first block presents a variety of commercial enterprises: T. Jones Jr.'s store for fruits, liquors, wines, and segars (sic), a variety of auctioneers and express services, with Sibell & Mott's Stationary and printing ending the block on the corner of Wall and Nassau. Moving along we come to the Custom House, now known as Federal Hall which stands beside the Bank of New York. The facade of this building now stands in the American wing of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The rest of the block is occupied almost exclusively by banks. The next block (3rd row from bottom) is dedicated almost entirely to insurance companies with the exception of the Bank of New York, the first banking building on Wall Street. As we approach the East River, the Tontine Coffee house comes into view on the corner of Wall and Water. A variety of industries were represented on this last block. A cotton broker, chronometer, bookbinder, and tobacconist among others occupied these addresses.

NEW YORK IN 1850

In the mid-19th century, cartographers and illustrators had neither helicopters nor satellites to assist them in their map-making endeavors. Instead, panorama painters had to supplement their knowledge of local geography with maps, up-to-date building directories, and a healthy imagination to accurately inform their impossibly lofty portrayals of the city.

This is a view of Manhattan's southern tip, looking north, published around 1850. An exceptional example of three stone lithography and hand-colored, it depicts parts of New Jersey and Brooklyn on the left and right sides respectively. Also notice the somewhat exaggerated detail of the buildings on Wall Street. This suggests the artist's (and emphasizes the general public's) high regard for Wall Street as an historical and economic beacon of the city.

Broadway is depicted as the city's most prominent street, bisecting the island. Trinity Church is located there at where Wall Street meets Broadway. The Merchant's Exchange dome is on the south eastern side and the Custom House's (soon to be taken over by the Sub-Treasury in 1862) colonnade is on the north side of the street facing south situated between the two aforementioned buildings. One begins to gain an understanding of how important and busy Broadway was from a very early point in history. Manhattan appears to be an elevated plane carved in two by the street. This map does an excellent job of depicting urban density at a uniform scale of height before the island was inundated by tall buildings.