The Museum's April 2010 to January 2011 exhibition The Rise of Wall Street was documented in an online version that was hard-coded and buggy. All the content of that site is transferred here on a new platform, but without changing tenses from present to past.

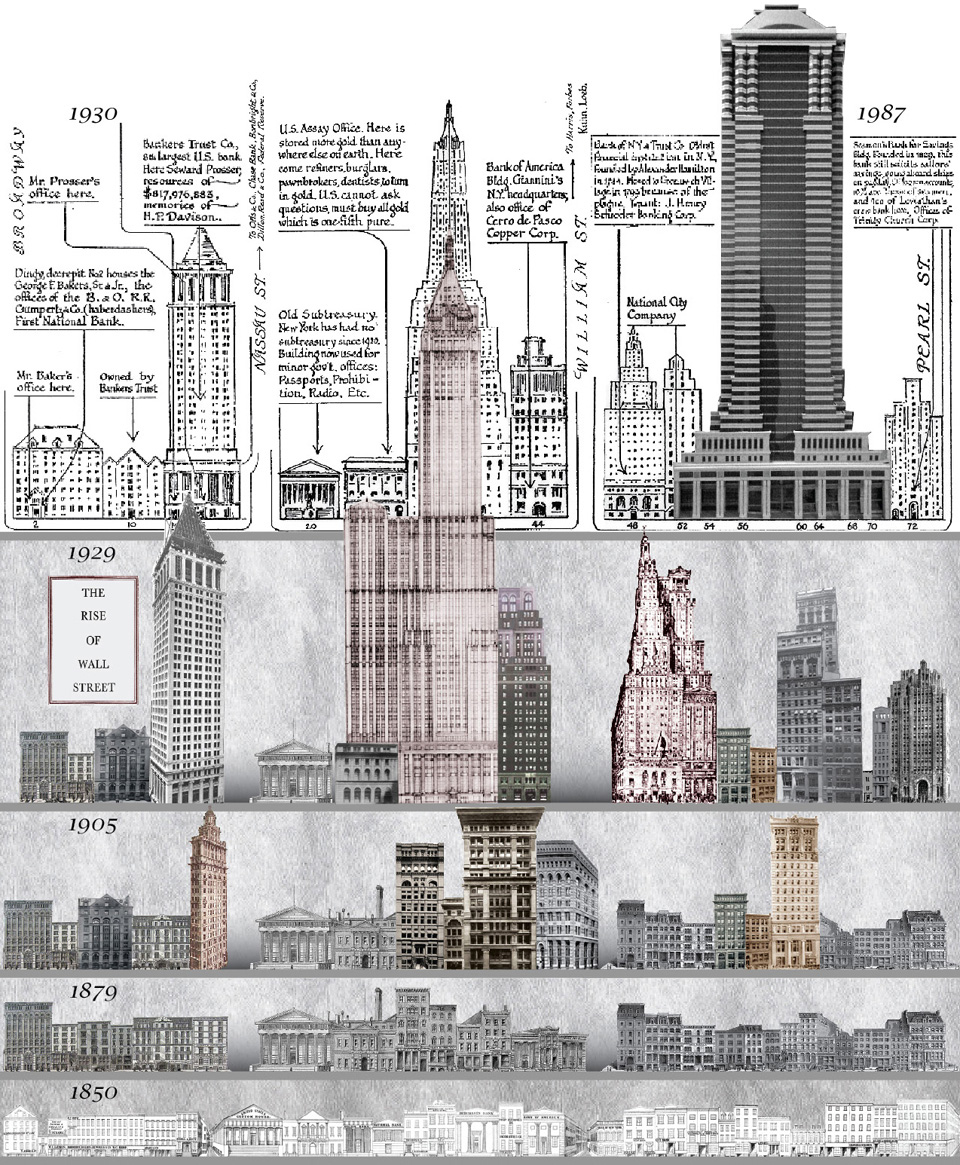

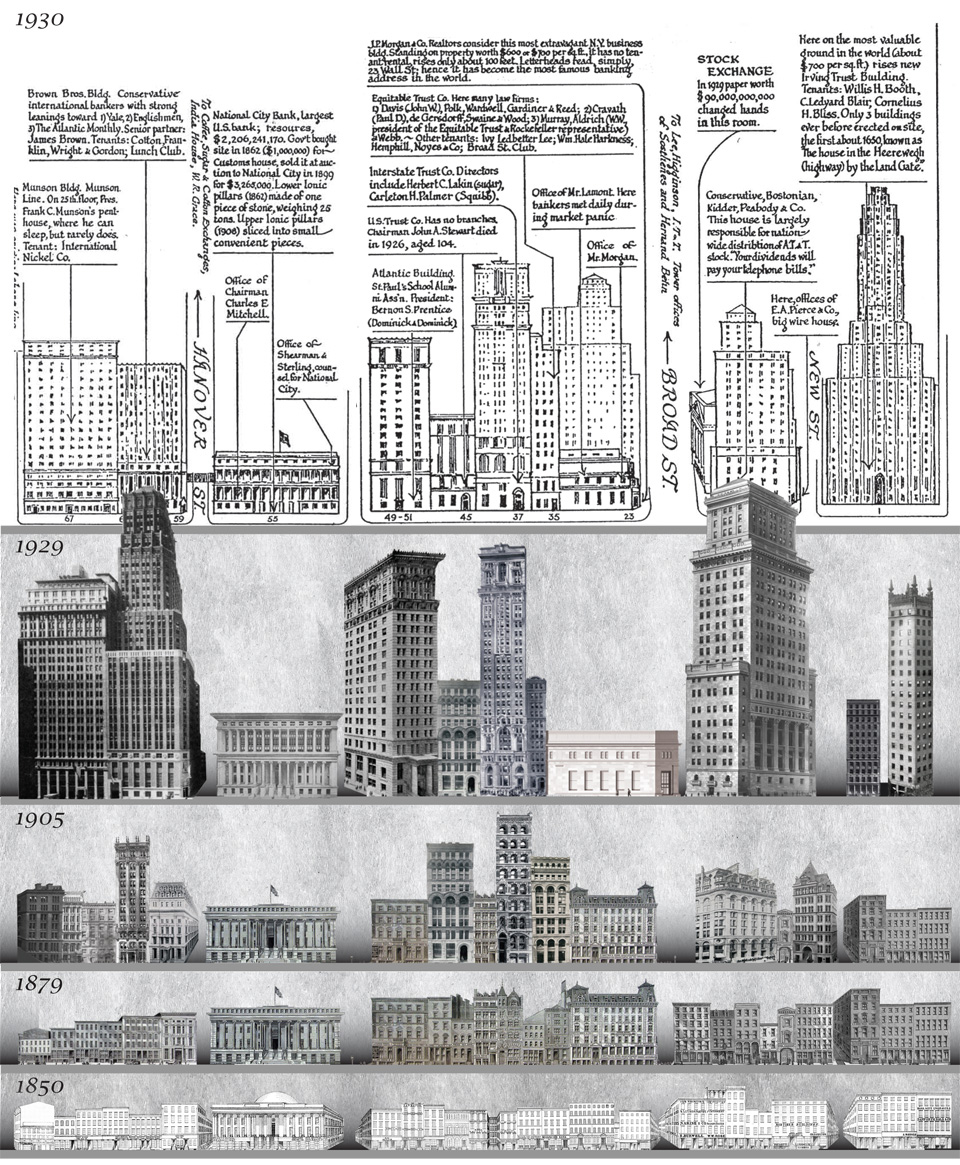

"Wall Street" is both a broad metaphor for the American center for global finance and a real place with an inordinately rich history layered into every lot of its nearly half-mile length, stretching from Trinity Church on Broadway to the East River. From colonial times, when the first bastions were erected to mark the edge of town, Wall Street has been continuously transformed, both in function --from commercial and residential to financial-- as well as in scale. Row houses were replaced by low-rise banks, then massive high-rise office buildings. The skyscrapers that line Wall Street today represent the climax species of an intense urban process. Documenting all buildings at Wall Street addresses since 1850, the exhibition demonstrates the cycles of growth that shaped the financial district over time, charting both the evolution from small to tall and the growing girth of buildings

enabled by new technologies and slow, but savvy site assembly.

Wall Street's high-rise history illustrates and exaggerates the typical story of skyscraper development expressed by the value of land and the demand for prime locations. As the district became the center of finance in the mid-19th century, Wall Street lots became the richest dirt on earth, selling at the highest prices per square foot ever recorded. The multiplicity of small lots and continuous occupation for more than 300 years also meant that Wall Street's big buildings represented the most expensive and challenging engineering and construction projects of their time. The exhibit explores how high stakes in architecture paralleled financial speculation at the heart of the capital of capitalism.

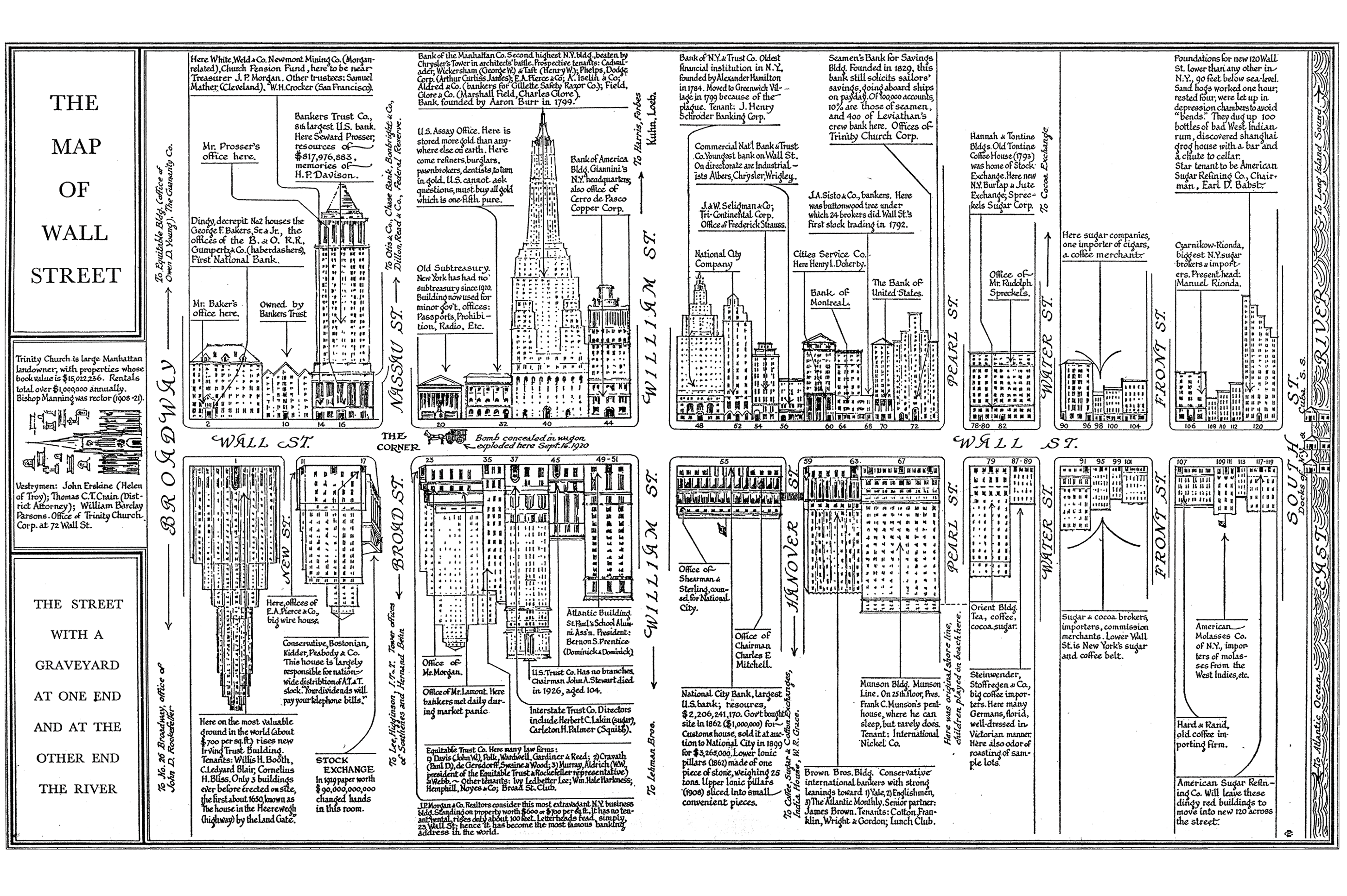

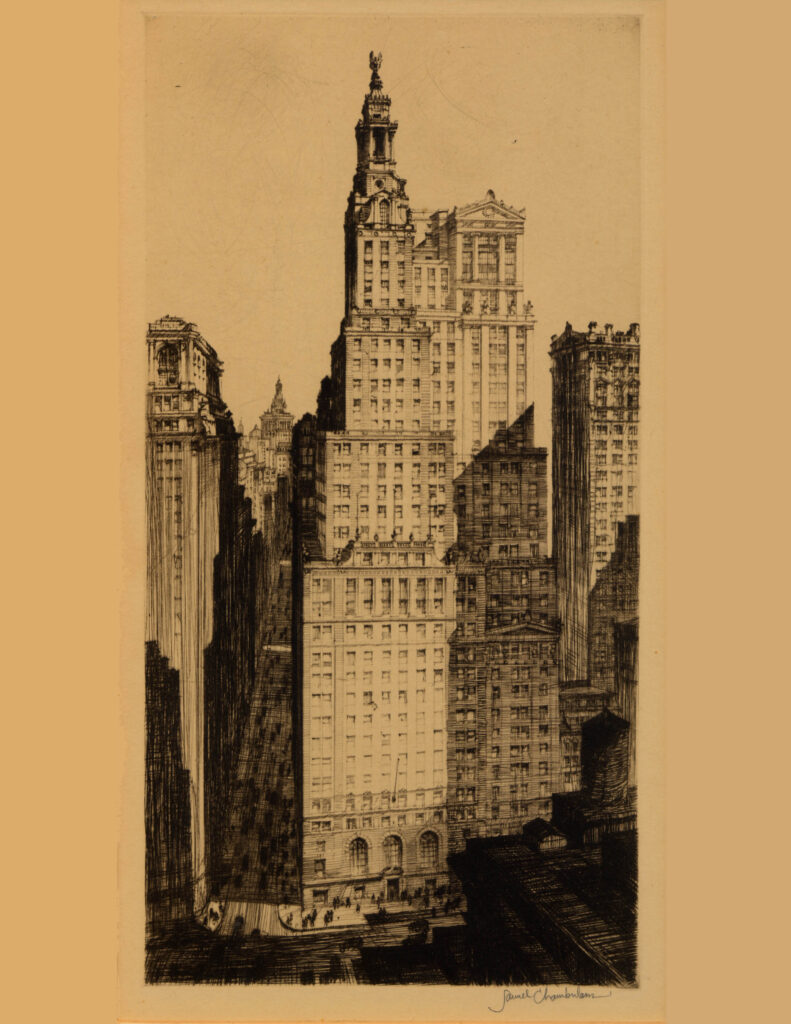

WALL STREET IN 1930

This mural is an enlargement of a drawing published in Fortune in March 1930-- the first year of publication of that magazine --as part of a five-article series on skyscrapers. The unnamed artist with the initials "CE" depicted the full length of Wall Street from Broadway to South Street, as the artist of the Lowenstrom panorama had done eighty years earlier. The major changes were all in the western end, where skyscrapers of 40 to 70 stories now climaxed most blocks. Between Water and Front streets, there remained many buildings of four to six stories that still functioned, as they did in the mid-19th century, as the offices and exchanges for commodities brokers of sugar, molasses, coffee, and cocoa.

Fortune's focus on business and finance guided the amusing and informative captions that emphasized the various buildings' resident bankers, executives, and substantial gold reserves.

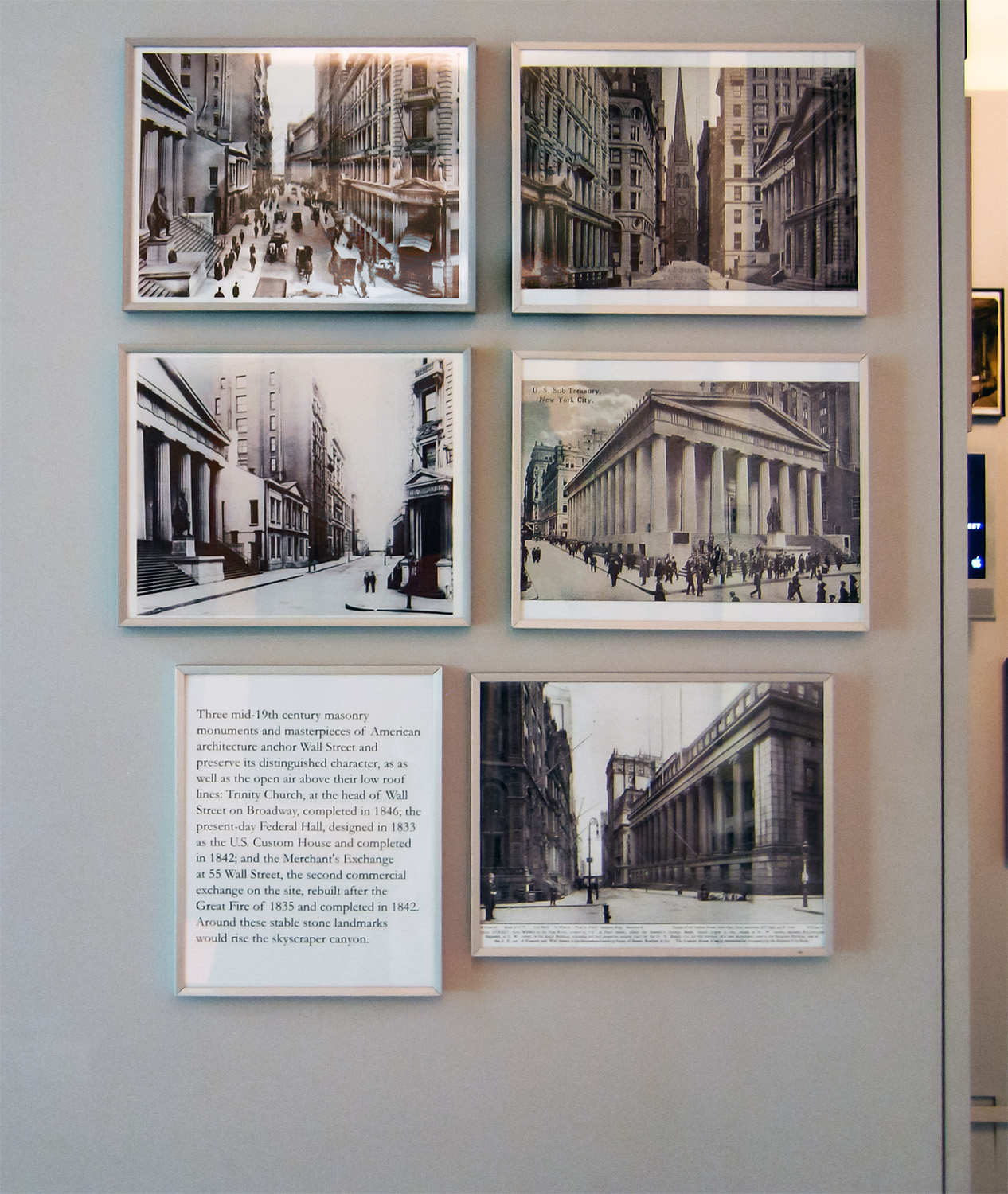

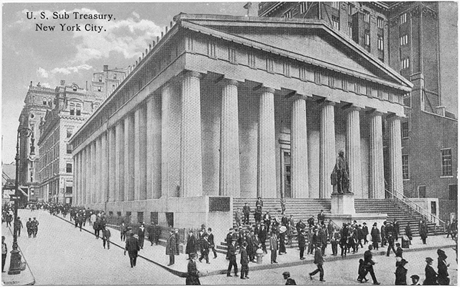

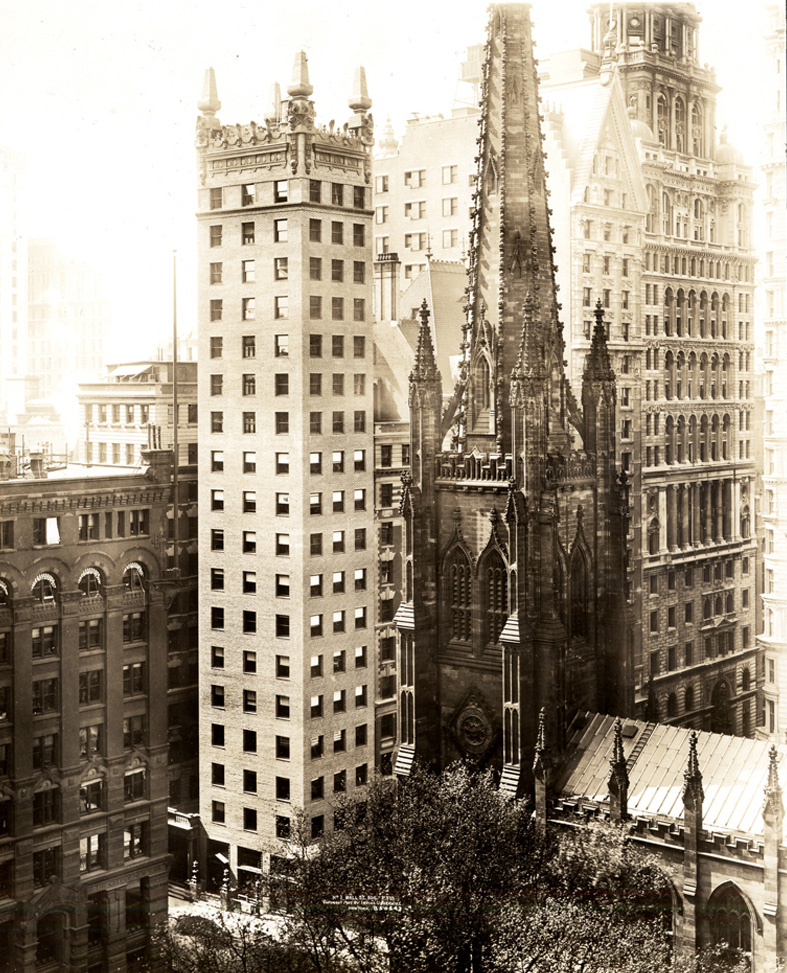

THREE MID-19TH CENTURY MASONRY BUILDINGS

Three mid-19th century masonry monuments and masterpieces of American architecture anchor Wall Street and preserve its distinguished character, as as well as the open air above their low roof lines: Trinity Church, at the head of Wall Street on Broadway, completed in 1846; the present-day Federal Hall, designed in 1833 as the U.S. Custom House and completed in 1842; and the Merchant's Exchange at 55 Wall Street, the second commercial exchange on the site, rebuilt after the Great Fire of 1835 and completed in 1842. Around these stable stone landmarks would rise the skyscraper canyon.

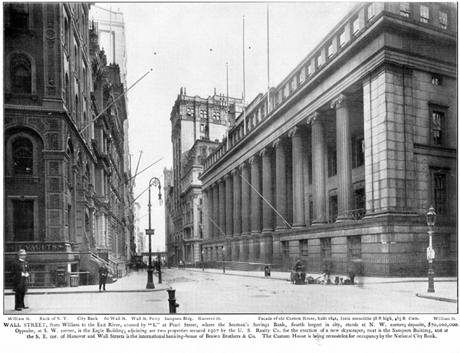

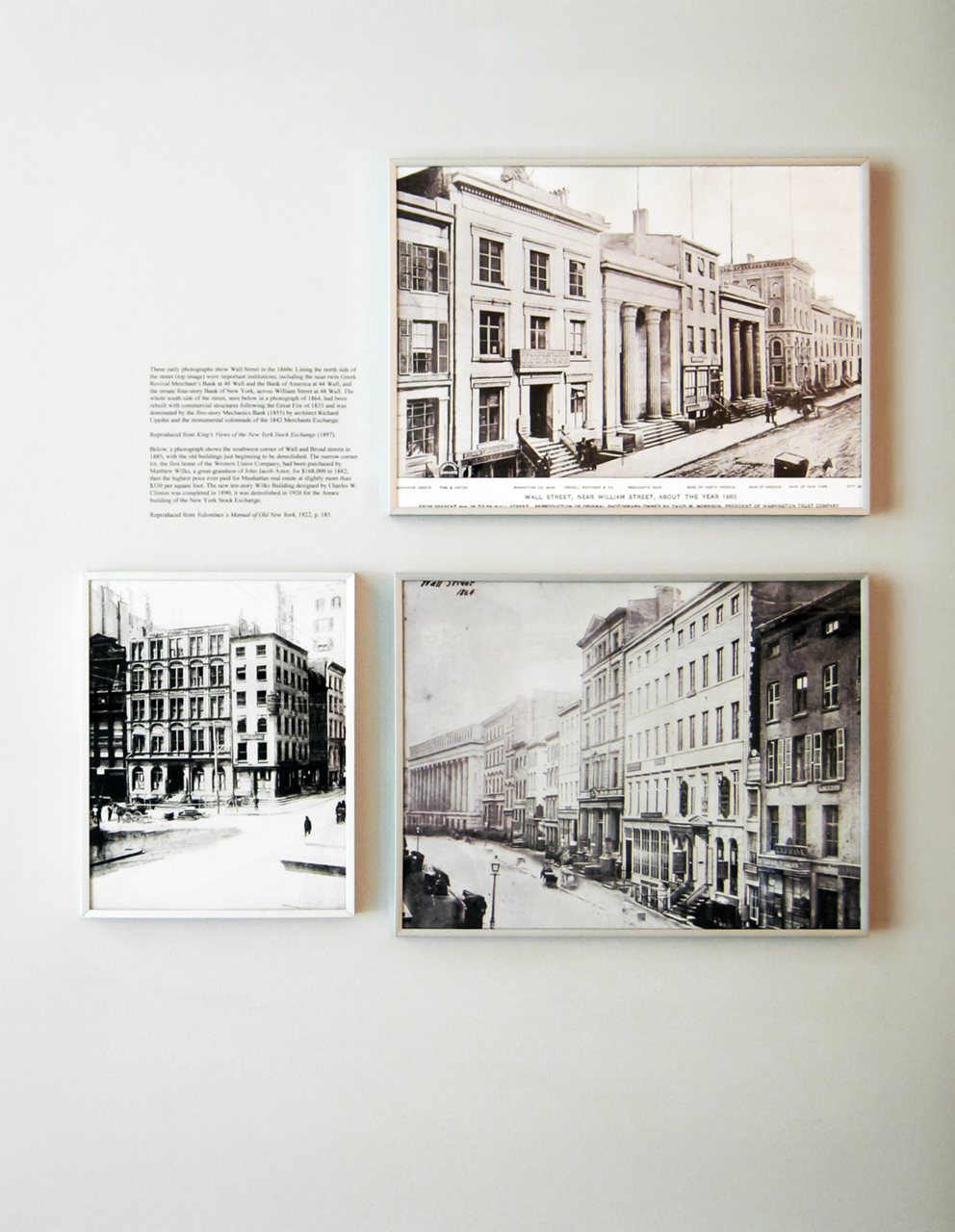

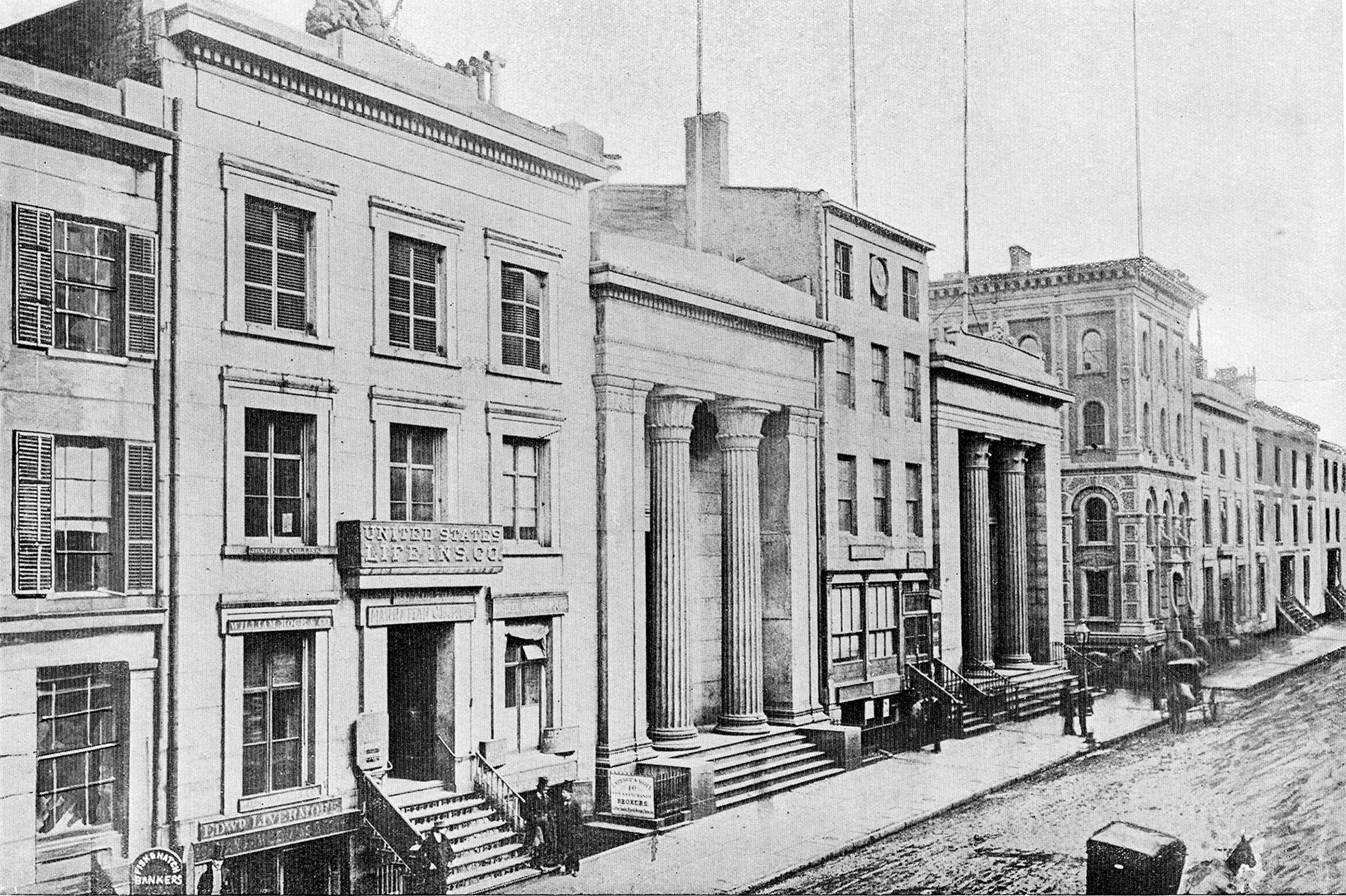

WALL STREET IN 1860s

These early photographs show Wall Street in the 1860s. Lining the north side of the street (top image) were important institutions, including the near-twin Greek Revival Merchant's Bank at 40 Wall and the Bank of America at 44 Wall, and the ornate four-story Bank of New York, across William Street at 48 Wall. [Click here to see the progression of the block from 30 and 40 Wall Street east to William Street.] The whole south side of the street, seen below in a photograph of 1864, had been rebuilt with commercial structures following the Great Fire of 1835 and was dominated by the five-story Mechanics Bank (1855) by architect Richard Upjohn and the monumental colonnade of the 1842 Merchants Exchange.

Below, a photograph shows the southwest corner of Wall and Broad streets in 1885, with the old buildings just beginning to be demolished. The narrow corner lot, the first home of the Western Union Company, had been purchased by Matthew Wilks, a great-grandson of John Jacob Astor, for $168,000 in 1882, then the highest price ever paid for Manhattan real estate at slightly more than $330 per square foot. The new ten-story Wilks Building designed by Charles W. Clinton was completed in 1890; it was demolished in 1920 for the Annex building of the New York Stock Exchange.

Models featured in case researched and created by Ondel Hylton.

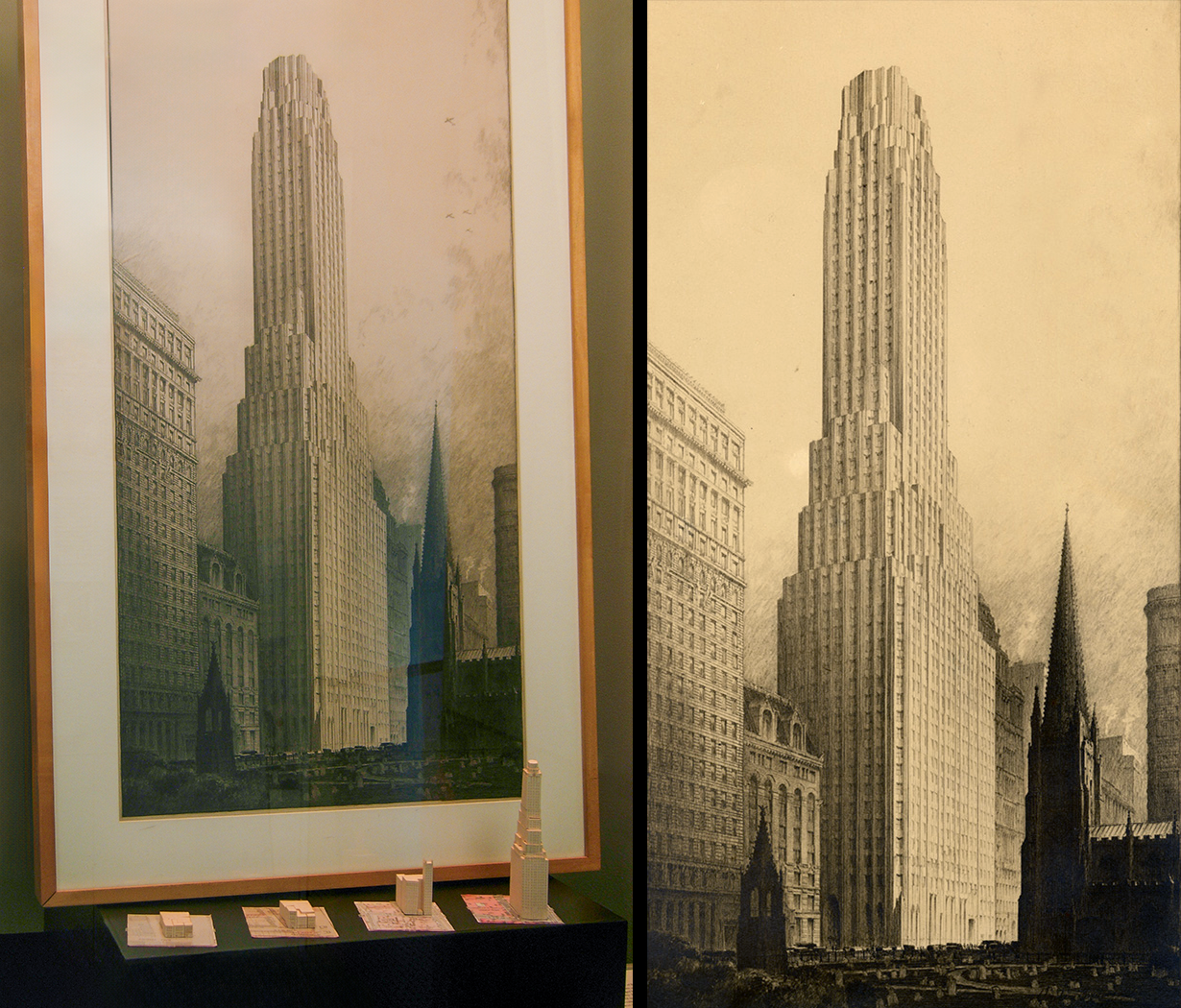

Wall Street/ Irving Trust Company Building, 1931 Designed by Ralph T. Walker of the firm Voorhees, Gmelin & Walker Rendering by Chester B. Price, 1930. On loan from HLW International LLP.

Left to Right: Irving Underhill; 1902, 1929, 1931; Collection of The Skyscraper Museum

The Chimney Building, Irving Underhill, 1907.

Aerial view of 1 Wall construction site, Irving Underhill, October 1, 1929.

SOUTH SIDE

1 Wall Street

1 Wall Street, at the southern corner of Broadway, has long been a prized address. In 1905, the 30' by 40' lot that had been occupied since the early 19th century by a four-story commercial building changed hands for the highest price per square foot ever recorded for Manhattan property: $615. The new owners, businessmen from St. Louis, erected a very plain 18-story tower on the site, multiplying the space (and rents) nearly five times. The so-called "Chimney Building" squeezed two offices per floor onto the 1,200 sq. ft. parcel (an area about one quarter the size of this museum).

In 1928, the powerful interests of the Irving Trust Company purchased 1 Wall Street and the neighboring buildings to the corner of New Street. The new site was still narrow, only 77' on Wall Street, but stretched along Broadway for 178'. Consuming the full block frontage meant that the new building could rise with windows on all sides. The new 50-story skyscraper began construction in 1929: progress photographs on the exterior of this case show the foundation construction in the fall of 1929.

The tower design by Ralph Walker of the architectural firm of Voorhees, Gmelin & Walker is an Art Deco masterwork. The expensive limestone facade was sculpted in an unusual curtain-like surface that softened the play of light and shadow. On the ground floor, a grand banking hall, the famous "Red Room," was faced in red and gold mosaics with a theatrical effect. The bank leased the 11th through 45th floors, but kept the top stories for executive offices and a lavish boardroom. The magnificent rendering by the delineator Chester B. Price displayed here conveys the monumental dignity of the building as seen from Broadway, across the cemetery of Trinity Church.

A series of photographs on the opposite side of this case documents the three successive buildings at 1 Wall Street.

Three photographs of 1902, 1929, and 1931 capture the views across Trinity Church cemetery and the corner of Broadway and Wall Street, revealilng the successive buildings that occupied the address 1 Wall Street.

The four-story building that occupied the site from the mid-19th century was demolished in 1905 for the 18-story "Chimney Building." A holdout property that long resisted development, the slender building was sold in 1929 to the Irving Trust Company for the highest price per sq. ft. price recorded to date. Irving Trust also purchased the neighboring properties, demolishing them all in 1929 and replacing the full-block with the Art Deco tower by Ralph Walker pictured in the rendering displayed in this case.

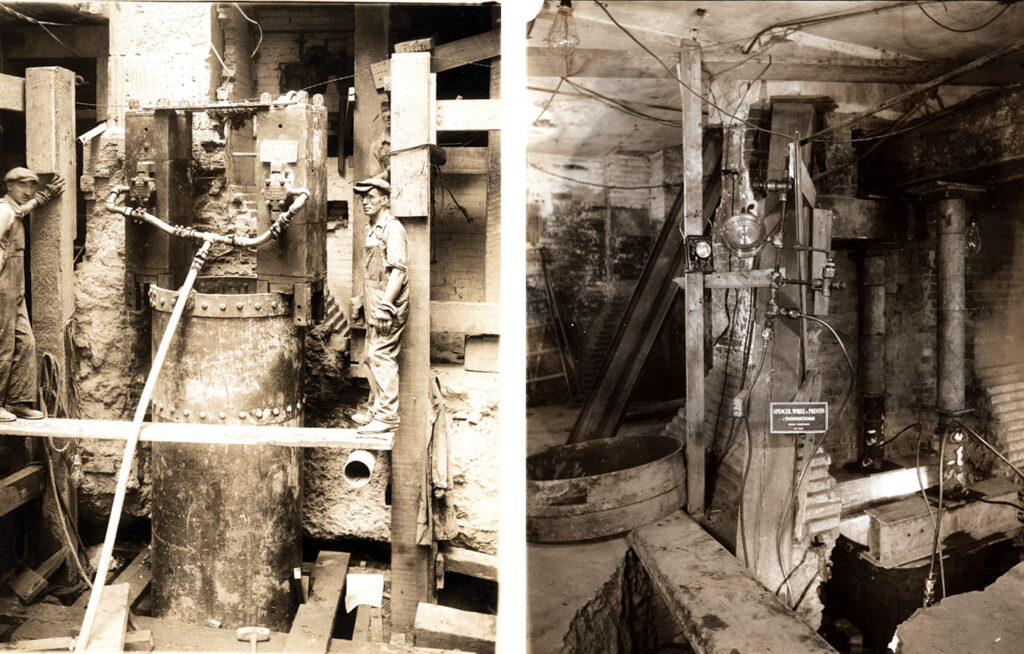

These progress photographs of the construction of the Irving Trust Co. Bank Building were commissioned by the foundation engineers Spencer, White & Prentis to document their work. In the top photograph, the rear of the New York Stock Exchange and Annex are visible across the excavated site. Below, a street-level view shows the impact of the work on Wall Street, with Trinity Church in the background.

All photographs on loan from Mueser Rutledge Consulting Engineers, the successor firm of Spencer, White & Prentis.

The New York Stock Exchange

The New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) has a Wall Street address, 11, based on the narrow entrance that leads to the main building that faces Broad Street. That imposing neo-classical temple with white marble columns and pediment of the NYSE was designed by architect George B. Post and completed in 1903, replacing the first home of the Exchange constructed on that site in 1865.

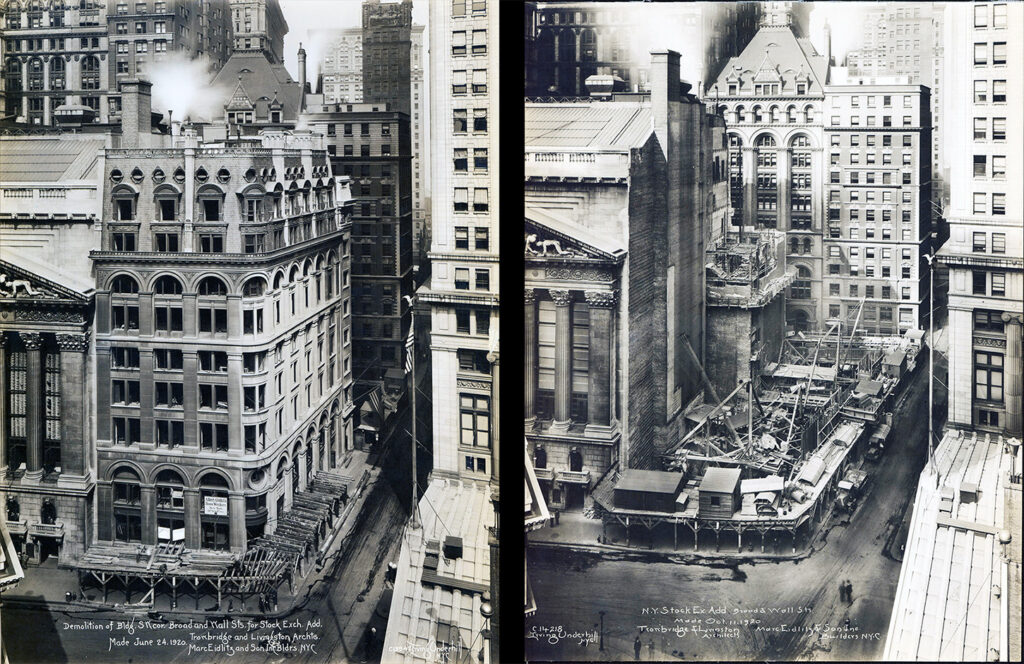

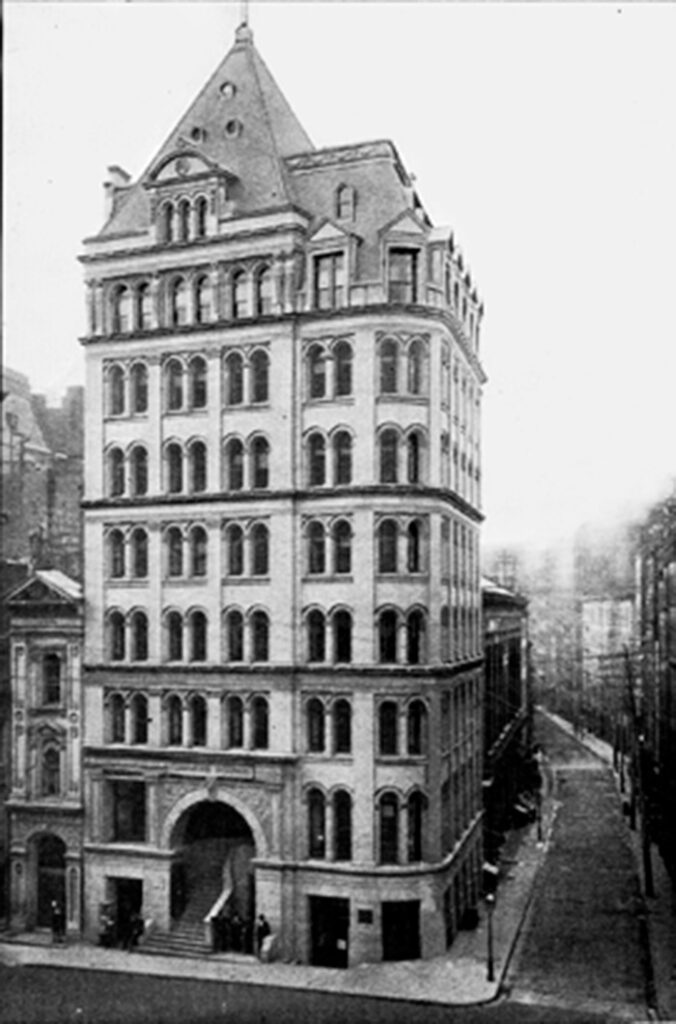

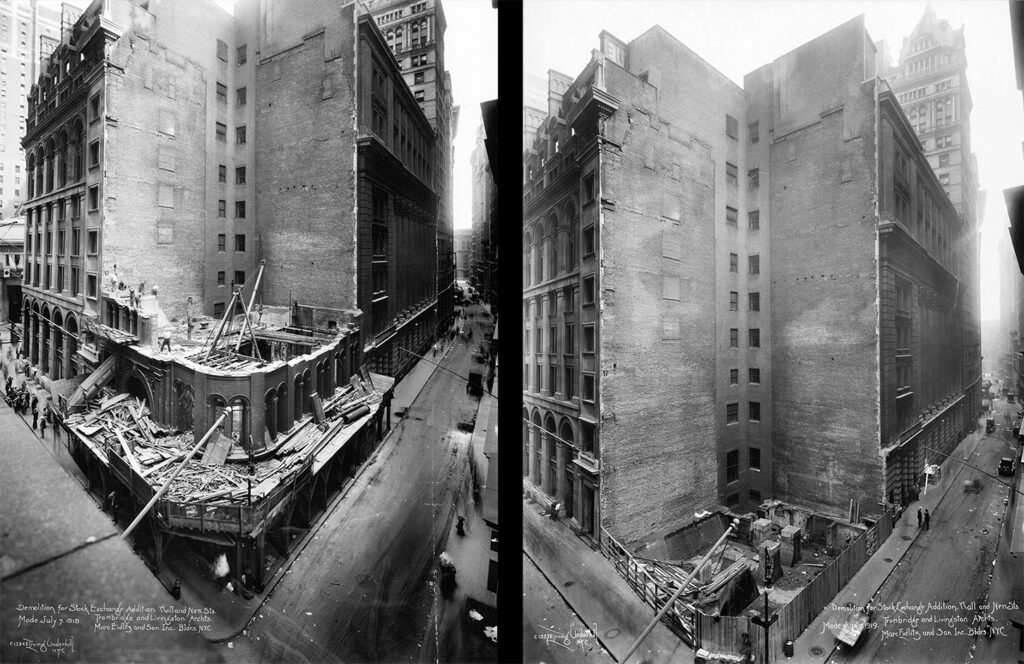

Below, a photograph shows the southwest corner of Wall and Broad streets in 1885, with demolition of the older buildings just beginning to make way for the new Wilks Building. The narrow corner lot, the first home of the Western Union Company, had been purchased in 1882 by Matthew Wilks for $168,000, which at slightly more than $330 per sq. ft. was the highest price yet paid for Manhattan real estate. Wilks had also purchased five smaller lots on Wall and Broad streets between 1876 and 1884 for a total of $891,000.

The new ten-story Wilks Building, designed by the prolific Charles W. Clinton and was completed in 1890, featured a rounded corner and steep mansard roof with three chimneys. It joined the nine-story Mortimer Building, designed by George B. Post and completed in 1885, to fill the block from Broad Street to New Street. The demolition of the Mortimer Building in 1919 is shown in the photographs at the lower right when, along with the Wilks Building, it was demolished for the 23-story Annex of the New York Stock Exchange, designed by the firm Trowbridge and Livingston.

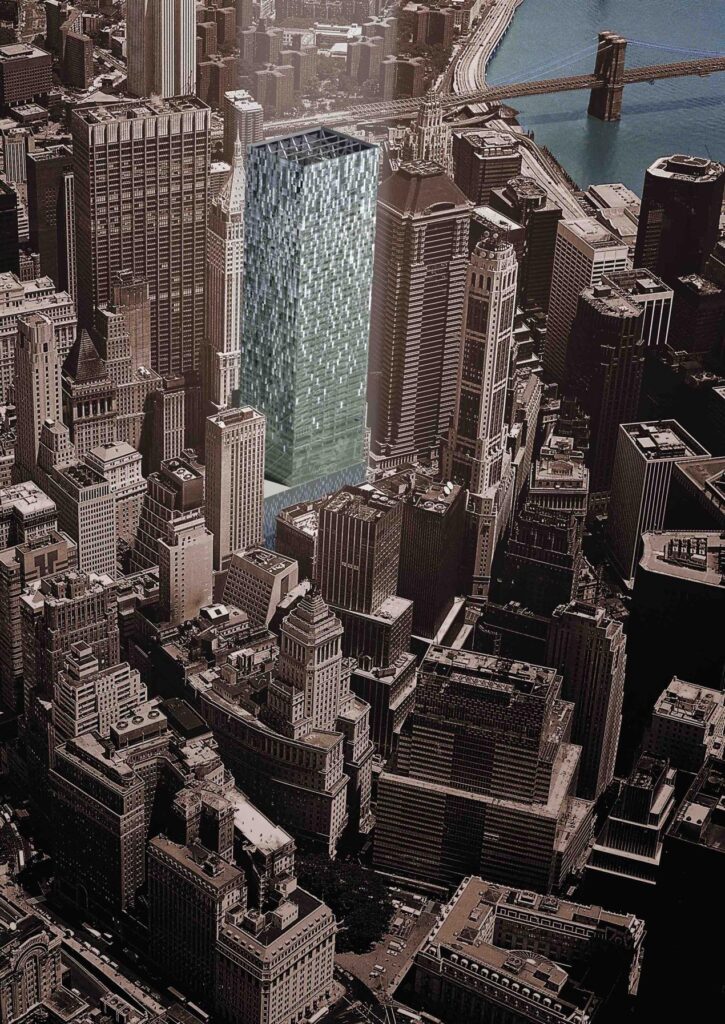

Stock Exchange Project: 33 Wall Street

The historical pattern of turning a full block of small lots into a single, or pair of very big buildings threatened to consume the south side of Wall Street between Broad and William streets and Exchange Place. In 2000, the leadership of the New York Stock Exchange pressured the City, then the Giuliani Administration, to create the conditions for a new home, with a more technologically advanced trading floor and other facilities. After considering several sites, they settled on the block across Broad Street from the NYSE's address since 1865. The City promised to assist with the site assembly.

The triple-height NYSE "Box" would occupy the full block, covering approximately 78,150 square feet. The NYSE Box itself was designed to contain 600,000 gross square feet with a custom trading and trading support facility. The main NYSE lobby was to be entered at Broad Street, where the structure measured 175 feet tall. The third floor of the Box would house the 50,000 gross square feet, multi-story, column-free trading floor and high-tech services for the trading operations.

Above the Box, a Class "A" office Tower of approximately 1,300,000 gross square feet and approximately 35-40 floors. Expanding upwards the openness created by the Box's mezzanines, the Tower is designed with a clear span over the Trading Floors using multi-story steel trusses that transfer the tower loads (gravity and wind) to columns along the perimeter of the Box. The office Tower will be accessed through a separate lobby directly off Wall Street, the second floor of the Box.

The Clarett Group acted as Development Consultant to the City and State of New York for the development of the New York Stock Exchange building and tower, a planned 1.8 million square foot project. Clarett oversaw the design development of the entire project with architecture firm Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, and marketed the office tower component to potential tenants and investors. The project was abandoned following 9/11.

The specimen stock certificate, reproduced from the collection of Mark Tomasko, depicts "The Corner" headquarters of J. P. Morgan & Co.

Case background image, Collection of The Skyscraper Museum.

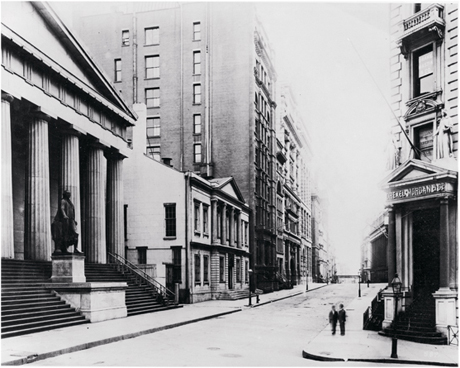

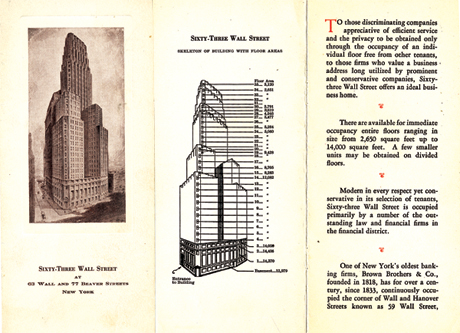

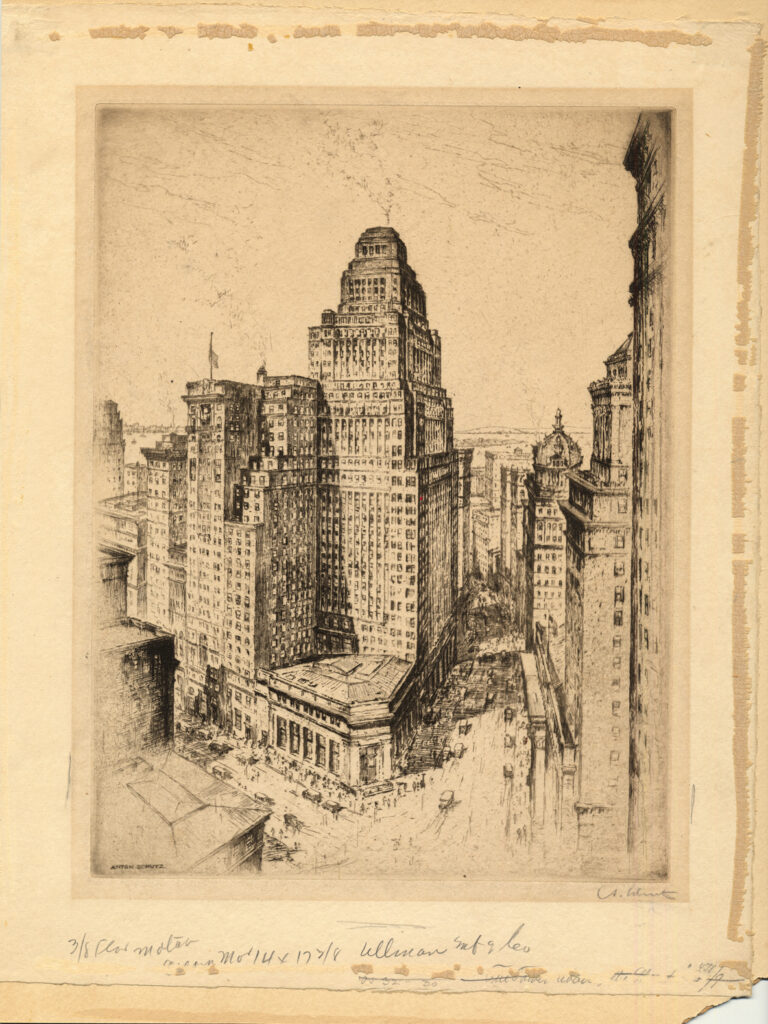

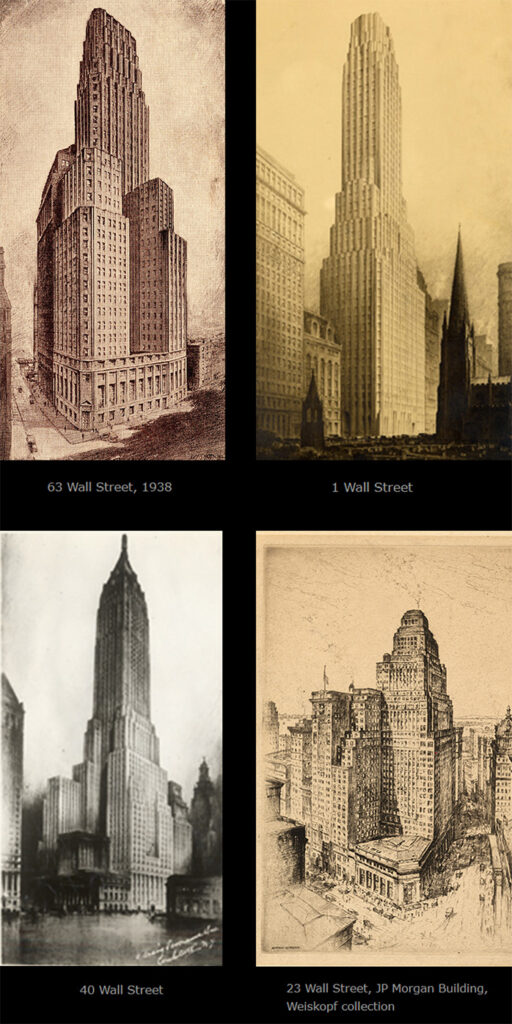

23 and 63 Wall Street

The intersection of Wall and Broad streets, with Nassau Street continuing north, has been the magnetic center of the financial district since the mid 19th century. The buildings and institutions that set the status of the place were the New York Stock Exchange, since 1865 based only a few steps from the corner, but on Broad Street; Federal Hall, which was erected as the U. S. Custom House from 1833-1842 and became the U. S. Sub-Treasury in 1862, when millions in gold and silver were held in its vaults; and the headquarters of J. P. Morgan & Co., long the country's most powerful investment bank, which occupied the address 23 Wall Street, known simply as "the Corner" in the current building from its completion in 1914 until 1989. Before constructing its 3-story limestone monument with its chamfered corner entrance, J. P. Morgan occupied space in the 6-story Drexel Building (completed 1873), so one exceptionally unusual aspect of the 1914 building was the fact that a shorter building replaced a taller one, contradicting the cardinal rule of Wall Street development.

The view from on high-- the boardroom or corner office-- holds as much the prestige as a prime address on Wall Street. The photograph on the back on this case captures the view from the top floor of 63 Wall in the early 1930s, looking north past the tower of 40 Wall, to the white Woolworth Building, world's tallest in 1913, and to the silhouette of the Empire State Building in midtown.

The framed photographs of lower Manhattan were taken in 1912 from the top floor of the newly completed Bankers Trust tower at 14 Wall. Looking south to the harbor, the buildings on Broad Street and near the waterfront are low-rise. Below, looking northwest are the tall towers that line Broadway, at center, the Singer Building and its wrap-around neighbor the City Investing Company Building, which on their joint completion in 1908 were the tallest and largest (in volume) office buildings in the world.

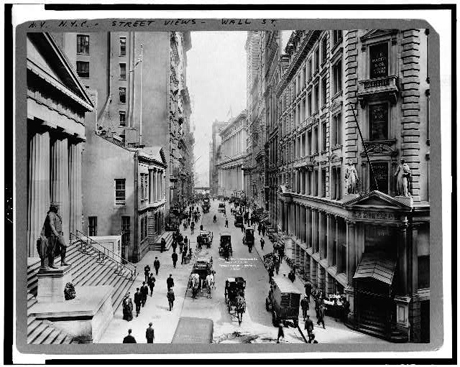

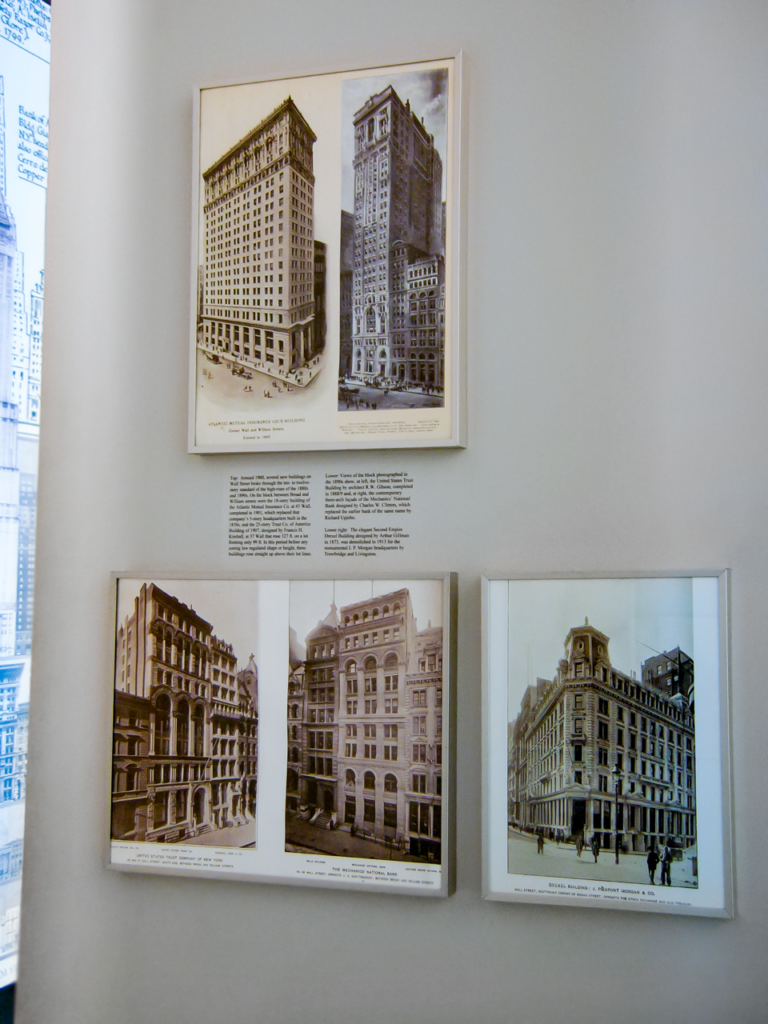

Views of Wall Street Between Broad and William Streets

Around 1900, several new buildings on Wall Street broke through the ten- to twelve-story standard of the high-rises of the 1880s and 1890s. On the block between Broad and William streets were the 18-story building of the Atlantic Mutual Insurance Co. at 45 Wall, completed in 1901, which replaced that company's 5-story headquarters built in the 1850s, and the 25-story Trust Co. of America Building of 1907, designed by Francis H. Kimball, at 37 Wall that rose 327 ft. on a lot fronting only 99 ft. In this period before any zoning law regulated shape or height, these buildings rose straight up above their lot lines.

Views of the block photographed in the 1890s show, at left, the United States Trust Building by architect R.W. Gibson, completed in 1888/9 and, at right, the contemporary three-arch facade of the Mechanics' National Bank designed by Charles W. Clinton, which replaced the earlier bank of the same name by Richard Upjohn.

The elegant Second Empire Drexel Building designed by Arthur Gillman in 1873, was demolished in 1913 for the monumental J. P. Morgan headquarters by Trowbridge and Livingston.

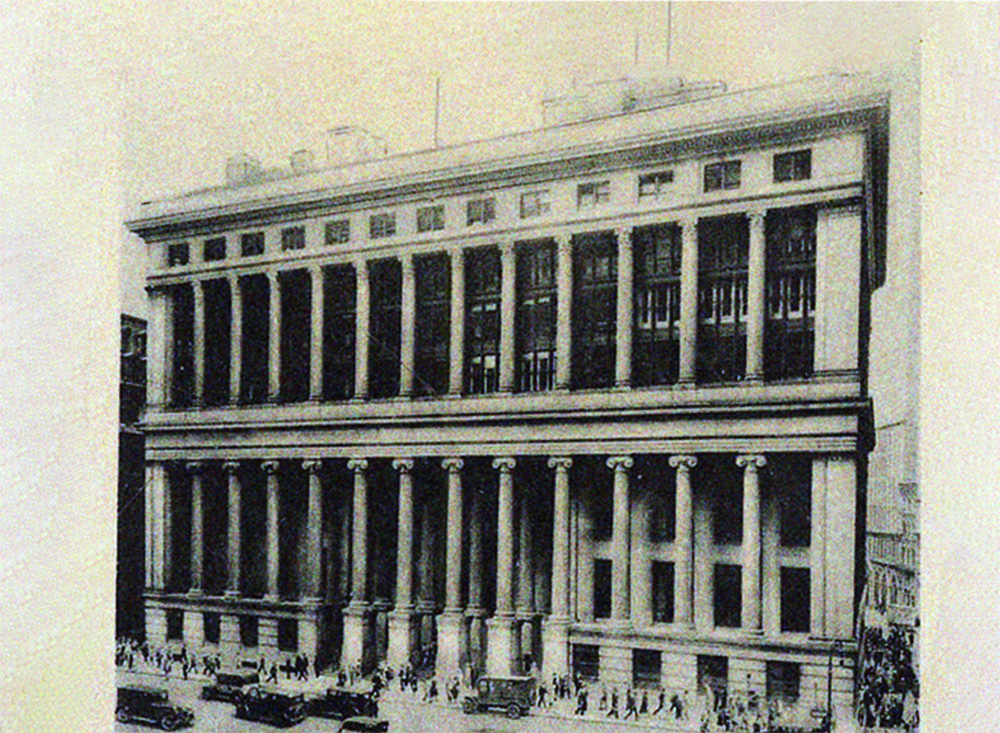

55 Wall Street

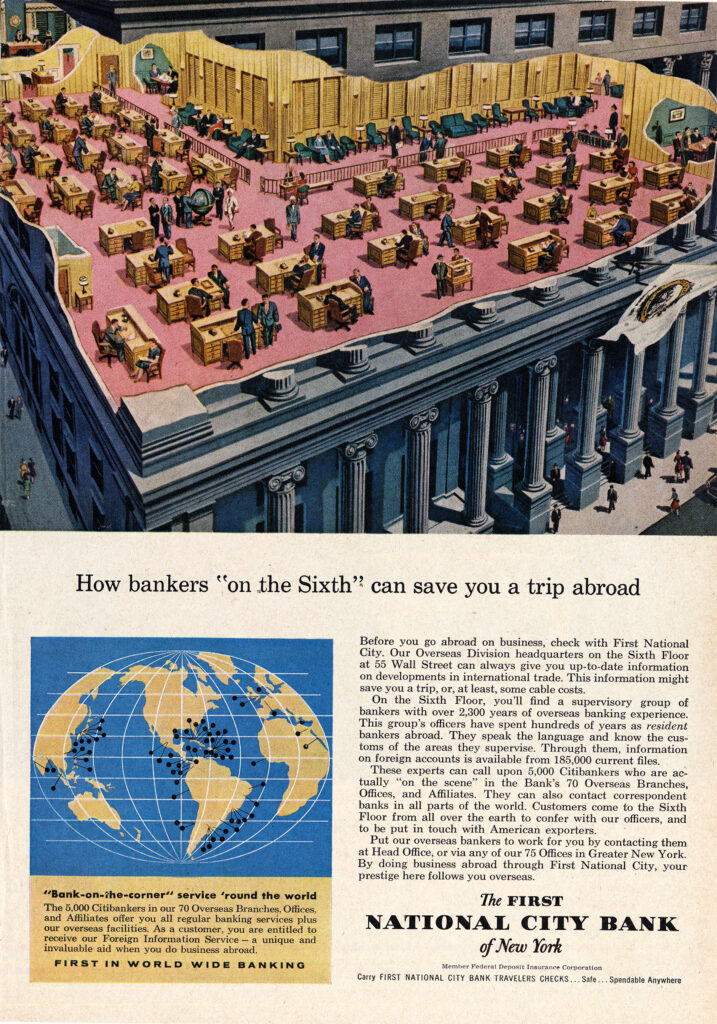

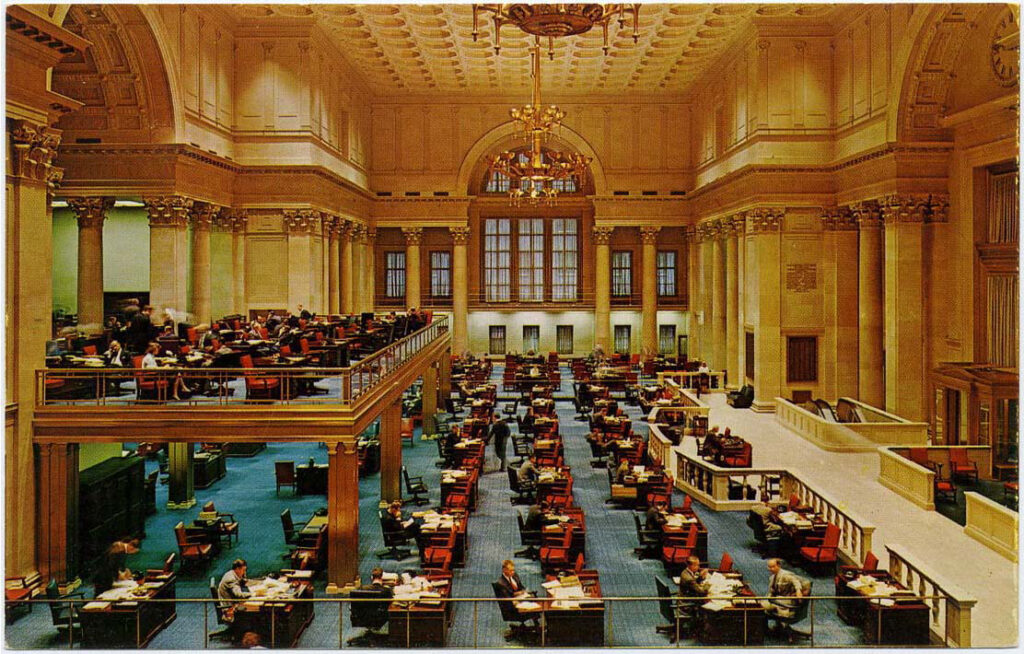

In 1901, architects McKim, Mead & White were hired to enlarge the mid-19th century monument, the second Merchant's Exchange, as the new headquarters of the powerful National City Bank, which had been located across the street at 52 Wall since 1812. The classicists doubled the height of the Wall Street facade by adding a row of Corinthian columns above the orriginal Ionic colonnade. The interior was completely rebuilt, evoking the grand scale of Roman baths, or the same architects' Pennsylvania Station, with a cruciform banking hall, offices at corners, and upper floors for additional departments for international and domestic banking. The bank opened for business 1908, but was not completed until 1910.

Depicted is a feature article in Fortune in March 1931, photographed by Margaret Bourke-White, the banking hall contains an elaborate tellers' cage as an island in the great room, and the operations of the institution are portrayed as the movement of vast amounts of paper. An advertisement of the 1950s (at left), touts the convenience of the transactions of the sixth floor Overseas Division, itself a sea of manned desks.

National City Bank kept its headquarters on Wall Street until 1961 when it relocated to 399 Park Avenue and converted 55 Wall into a branch bank. After multiple mergers, National City Bank became known as Citibank in 1974. In 1965, the exterior of 55 Wall was designated a New York City landmarkand in 1999, the banking hall interior was also protected by landmark status. In 1998, the building was adapted for use as the Regent Hotel, which closed in 2003. The banking hall is now operated as an event space by the Cipriani company and the hotel is condos and serviced apartments.

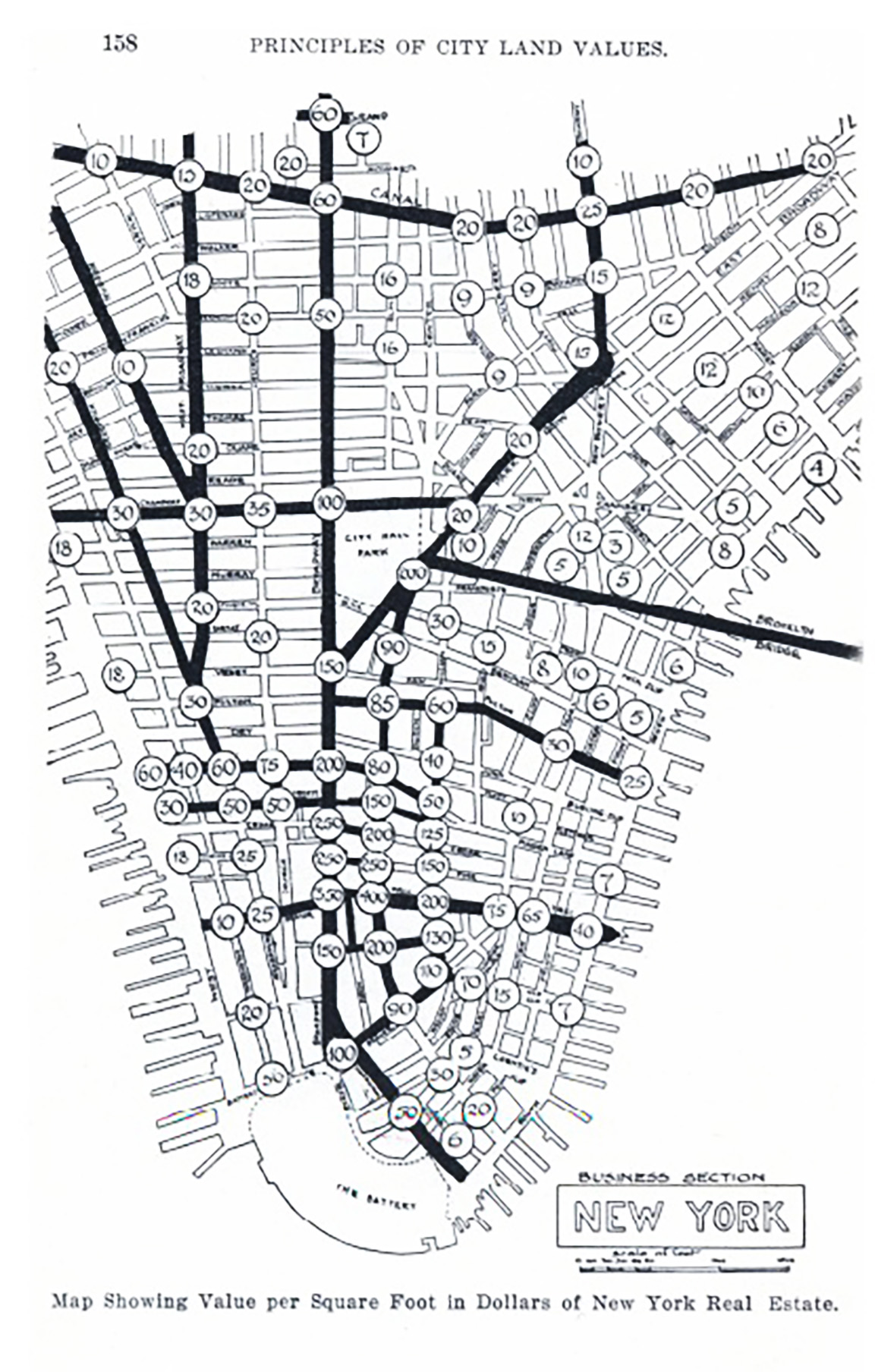

Map published in Richard M. Hurd,Principles of City Land Values. New York: The Real Estate Record and Builders Guide, 1908. pg. 158

Lower Manhattan Land Values

This 1903 map shows the wide range of land values across Lower Manhattan. The city's most expensive land, valued at $400 per square foot, was located on Wall Street at the intersection of Broad and Nassau streets, where the powerful financial institutions were headquartered, including the U.S. Sub-Treasury (in Federal Hall), the New York Stock Exchange, and the offices of investment banker J. P. Morgan at 23 Wall, then in the Drexel Building. The proximity and prestige of these institutions and companies drove the demand for a Wall Street address. High demand for the limited space produced high rents, high land values, and thus high-rise buildings, which clustered in the financial district around Wall Street, on lower Broadway, and near City Hall.

Also notable on the map is the disparity between the high and low values. Just a few blocks west of Wall Street, land values plummeted to $10 a sq. ft., and even along Wall Street near the East River, land values dropped to one-tenth the value of the premier blocks. The oft-repeated explanation for the island of Manhattan's skyscrapers- that buildings "grew upwards" because there was no room to "expand out," is contradicted by this 1903 map, which clearly shows the high prices that developers were willing to pay for some sites.

Models created by Ondel Hylton.

Video compilation the demolition of the Gillender Building and construction of the Bankers Trust Building and Annex, created from the collection of The Skyscraper Museum by Nicholas Crummey.

All photographs, collection of The Skyscraper Museum, Bankers Trust Collection.

NORTH SIDE

14 Wall Street

The Gillender Building and Bankers Trust Building & Annex

Multiple office buildings and two skyscrapers, the Gillender Building and the Bankers Trust Tower, have occupied the northwest corner of Wall and Nassau streets. The models here illustrate four moments in the development of this prime site and block: 1852, 1879, 1897, and 1916.

The value of the lot at the corner of Wall and Nassau streets rose more than tenfold by 1896, when the owners decided to replace the six-story Union Building with a 300-foot tall tower. The slender Gillender Building, then fourth tallest in the city at 306 feet to the tip of its spire, rose 22 stories on a site of only 26 x 73 feet.

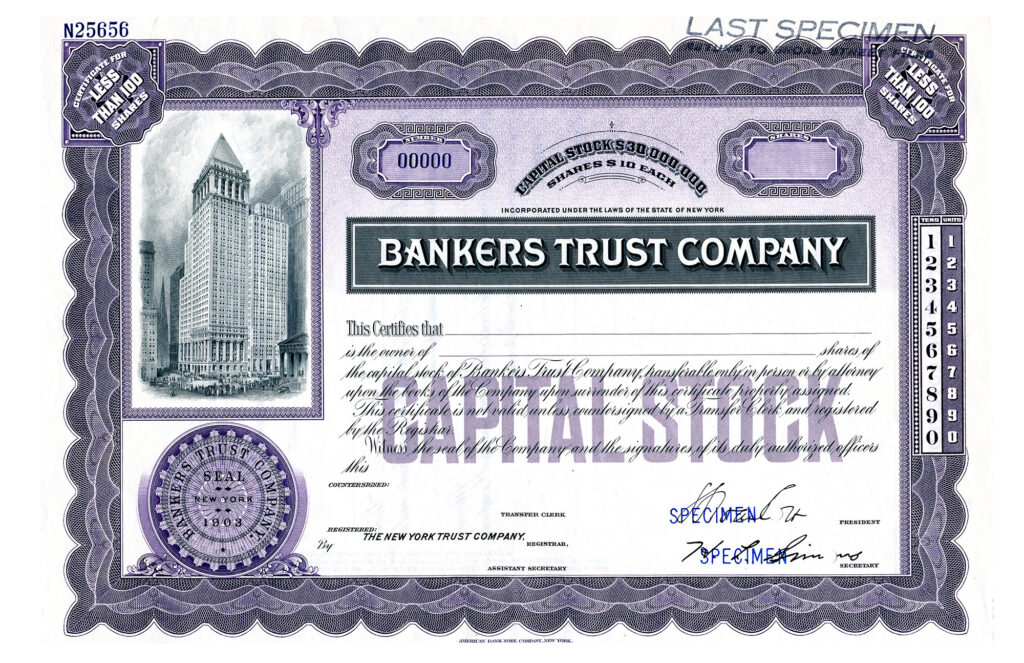

Twelve years later, the building and lot were sold to the Manhattan Trust Company for the highest price ever recorded, over $800 a square foot. The same year, the Bankers Trust Company absorbed the Manhattan Trust, negotiated a lease on the adjoining lot, and decided to replace the Gillender with a much larger structure on a combined lot 93 x 96 feet. At forty-one stories and 540 feet tall, the new Bankers Trust was the fifth tallest building in the city when it opened in 1912.

In 1931, the Bankers Trust Company acquired three neighbors: the Astor Building at 10 Wall Street, 7 Pine Street, and the Hanover National Bank and constructed an L-shaped annex that surrounded the original tower. Designed by Shreve, Lamb and Harmon, architects of the Empire State Building, this lavish Art Deco banking hall and annex more than tripled the building's rentable area.

14-20 Wall Street

The 7-story office building, known as the Union Building, occupied the corner site from 1879 to 1896, when it was replaced by the slender 20-story Gillender Building, which became Wall Street's tallest tower when it was completed in 1897.

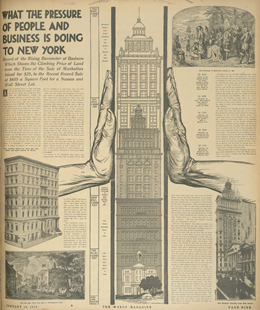

A reproduced page from the popular newspaper The World for Sunday, January 16, 1910, describes "the romance of real estate" that drove land prices on Wall Street, as well as new buildings, to dramatic heights. The paper noted that the value of land had increased from $56,000 in 1850 to $1.2 million in 1910.

A series of photographs charts construction progress on the Bankers Trust tower from May to August 1911. The steel frame is shown rising in the first photograph and near completion in the last, with the stone pyramid approaching its full height of 538 feet.

The specimen stock certificate for the Bankers Trust Company features a fine engraved image of the "Tower of Strength," seen after the addition of its annex building, designed by architects Shreve, Lamb & Harmon and completed in 1933.

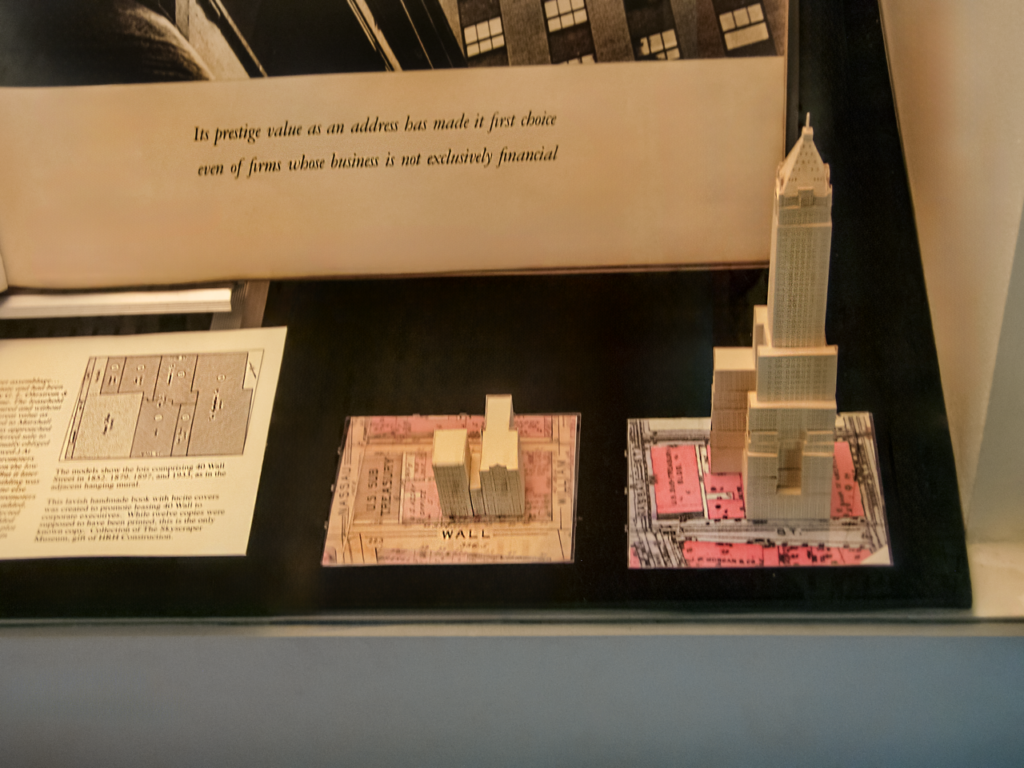

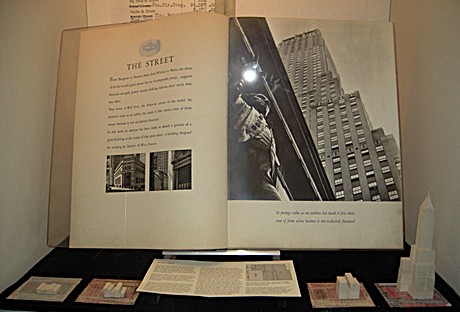

This lavish handmade book with lucite covers was created to promote leasing 40 Wall to corporate executives. While twelve copies were supposed to have been printed, this is the only known copy.

Collection of The Skyscraper Museum, gift of HRH Construction.

40 Wall Street

At seventy stories and 927 feet tall to the top of its spire, 40 Wall Street was the giant on its block. Famous in 1929, when it vied with the Chrysler Building to take the title of world's tallest building, 40 Wall lost the race by a spire- although both towers were soon surpassed by the Empire State Building.

Three major buildings fronting Wall Street were demolished for the skyscraper, as well as three on Pine Street. The strategic process of purchasing the many lots that allowed for such a large building was recounted in Fortune in an article in August 1930:

The property is attacked from the principal front, and the lots facing on that street are first secured. Then the secondary lots are taken. And by the time the gentlemen in possession of the rear lots have begun to suspect that their properties have key value to a great scheme, they find themselves cut off from the sun and with only one possible profitable movement- backwards and out.

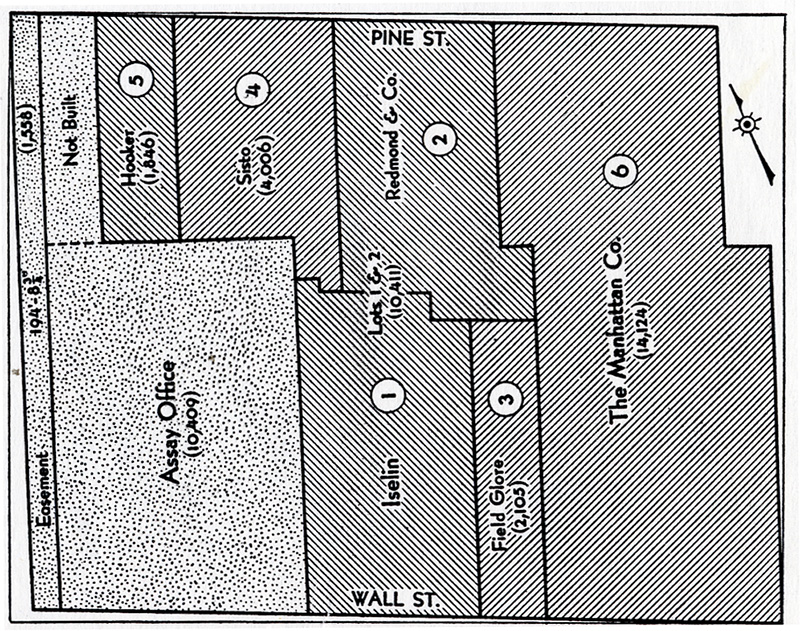

In the case of the 40 Wall Street assemblage... Lot 1 belonged to the Iselin estate and had been leased for ninety-three years by G. L. Ohrstrom & Co., the originators of the scheme. The leasehold of Lot 2 had previously been secured and without difficulty because it was only of great value as an adjunct to Lot 1. Lot 3 belonged to Marshall Field of Field, Glore. Mr. Field was approached and found to be amenable, but preferred sale to lease, and the promoters were eventually obliged to buy his land... (Lots 4 and 5 followed.) At this point it was the intention of the promoters to build on these five lots, depending on the low building of the Assay Office for light. But it later became known that the Assay Office building was for sale, and since its purchase by anyone else would jeopardize the entire scheme the promoters were forced to buy it. Before this lot was added, The Manhattan Company, owners of 6, elected to join the promoters, and their lot was added under leasehold, making the final building plot considerably larger, and certainly different in shape from the plot originally intended.

The models show the lots comprising 40 Wall Street in 1852. 1879. 1897, and 1933, as in the adjacent hanging mural in the gallery.

This lavish handmade book with lucite covers was created to promote leasing 40 Wall to corporate executives. While twelve copies were supposed to have been printed, this is the only known copy. Collection of The Skyscraper Museum, gift of HRH Construction.

Reproduced from King's Views of New York Stock Exchange (1897).

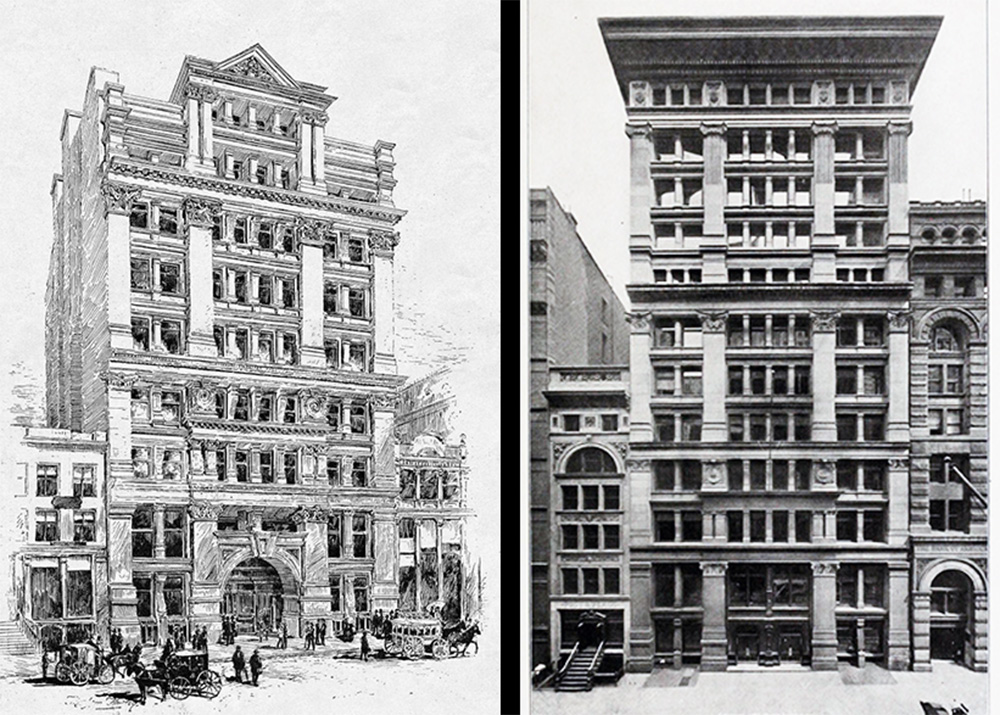

Left: Manhattan Bank and Merchants' Bank Building, rendering by Hughson Hawley, Harper's Weekly, January 31, 1885.

Right: "The Bank Building after remodeling," The Merchants' National Bank of the City of New York: A History of its First Century, p. 183. Retrieved from www.archive.org

Photograph of the north side of Wall Street from corner of Wall & Broad Streets. Mueser Rutledge Collection.

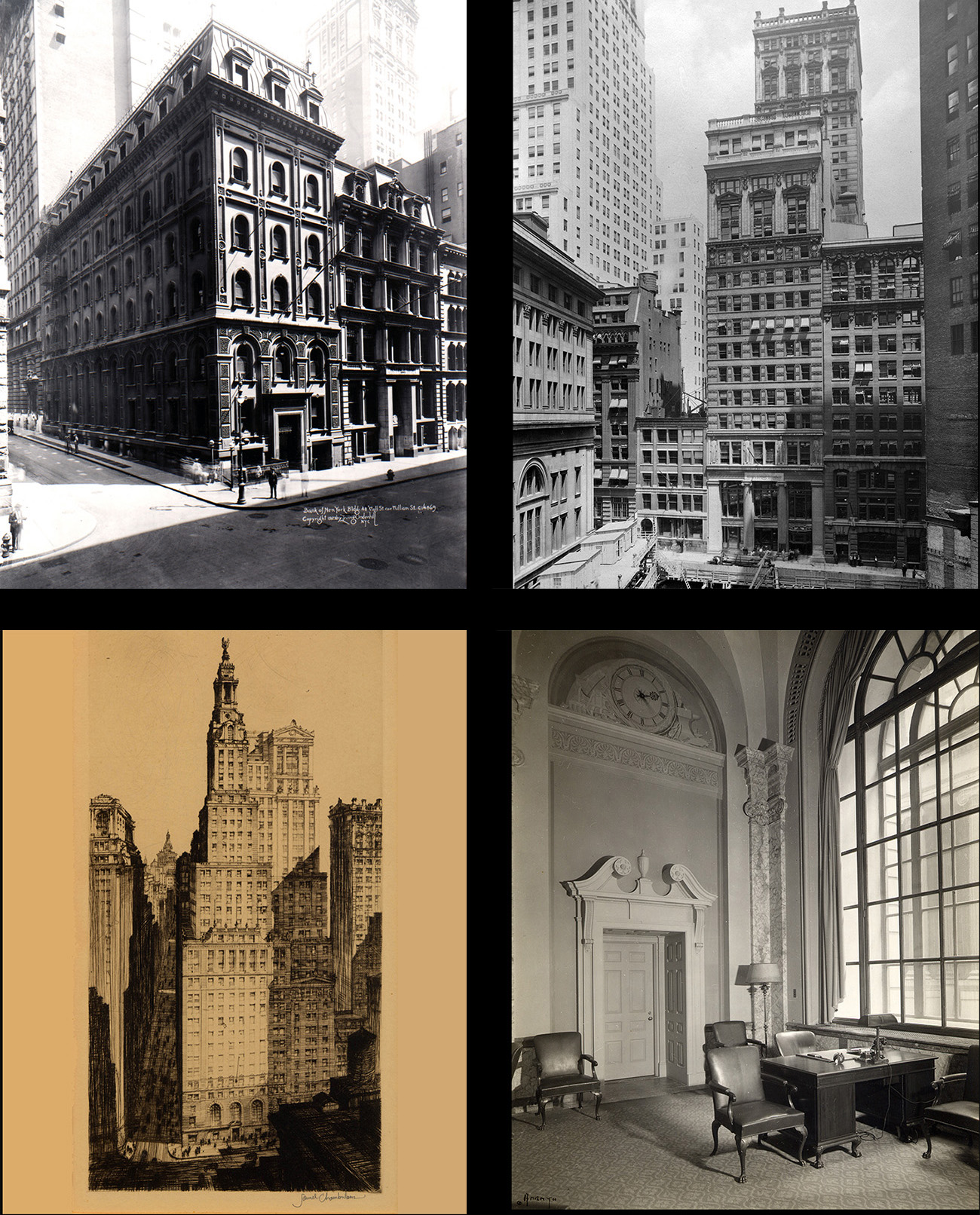

This group of images shows the successive buildings at the addresses from 30 and 40 Wall Street east to William Street: the corner site at 44 Wall was occupied by a series of buildings for the Bank of America. In addition to illustrating the progressive evolution from short to tall, they also capture a seldom-noted phenomenon of growth: adding a few additional stories to the existing structure.

The vertical extension and clever remodeling can be seen most clearly in the buildings above; the drawing on the left of the Manhattan and merchants' Bank building, designed by W. Wheeler Smith and completed in 1883, shows the heavy masonry of the nine-story structure with a pedimented roof line. On the right, the same building has grown by three stories and is capped by a deep projecting cornice, both added in 1903.

Likewise, the little building to the west (left) grows from four to six stories. In the photograph below it stretches to eight stories, without rebuilding the lower floors. This photo, which takes in the view east from outside "the Corner" headquarters of J.P. Morgan at 23 Wall, makes clear the massiveness of the sheer walled canyon of the block in the 1920s, just before demolition began for the 40 Wall Street skyscraper.

The address 40 Wall Street was long associated with the venerable Manhattan Company, established in 1799 to provide pure water (at a profit) to lower Manhattan, and its associated bank, known as the Bank of the Manhattan Company. Similarly, the Merchants' Bank occupied a building at 42 Wall Street since its establishment in 1803. The early photograph reproduced above shows the street in 1860, with the Manhattan and Merchants' banks designed in 1847-48 and 1839 respectively.

When first publicized, the 70-story skyscraper at 40 Wall Street was to be named the Bank of Manhattan Company Building. The bank was to be an anchor tenant, not the building's owner, who was a speculative developer, George Ohrstrom, and his investor partners. The elevation drawing at right, from the office of the architect H. Craig Severance, shows an intermediate version of the design, dated July 9, 1929, that envisioned a taller and more solid base structure and assumed that the 30 Wall Street site would be included within the development, which ultimately it was not.

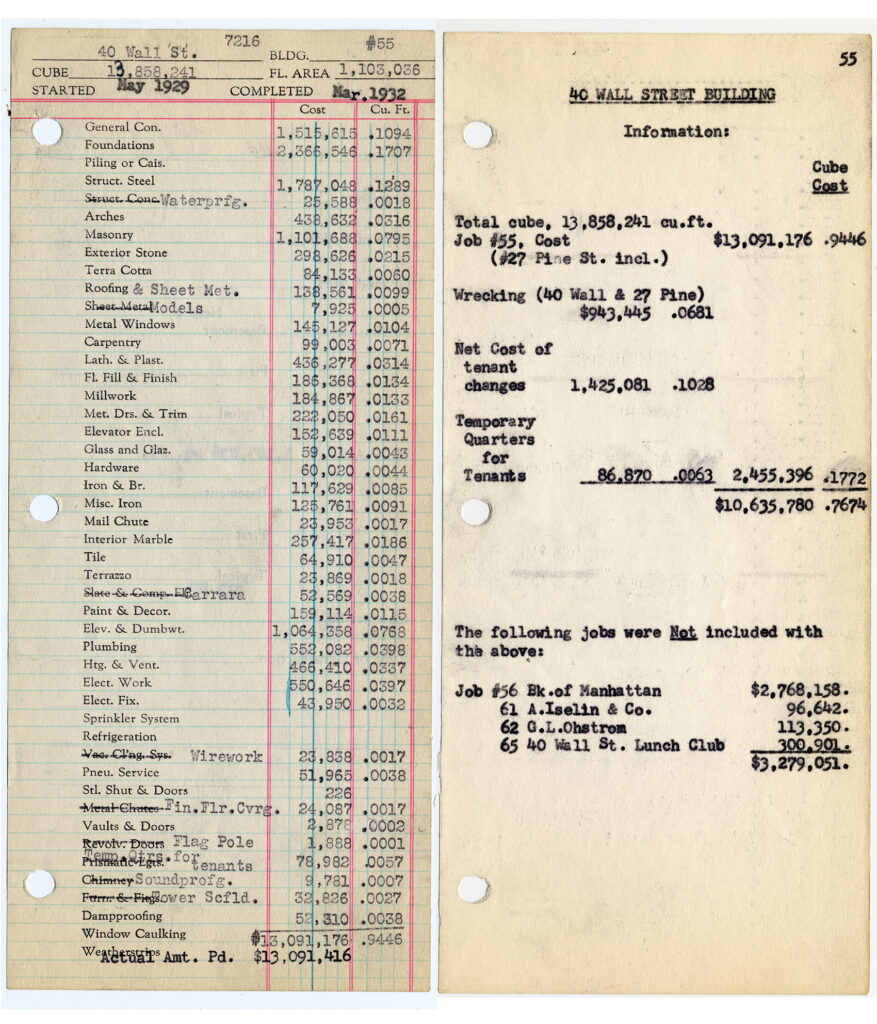

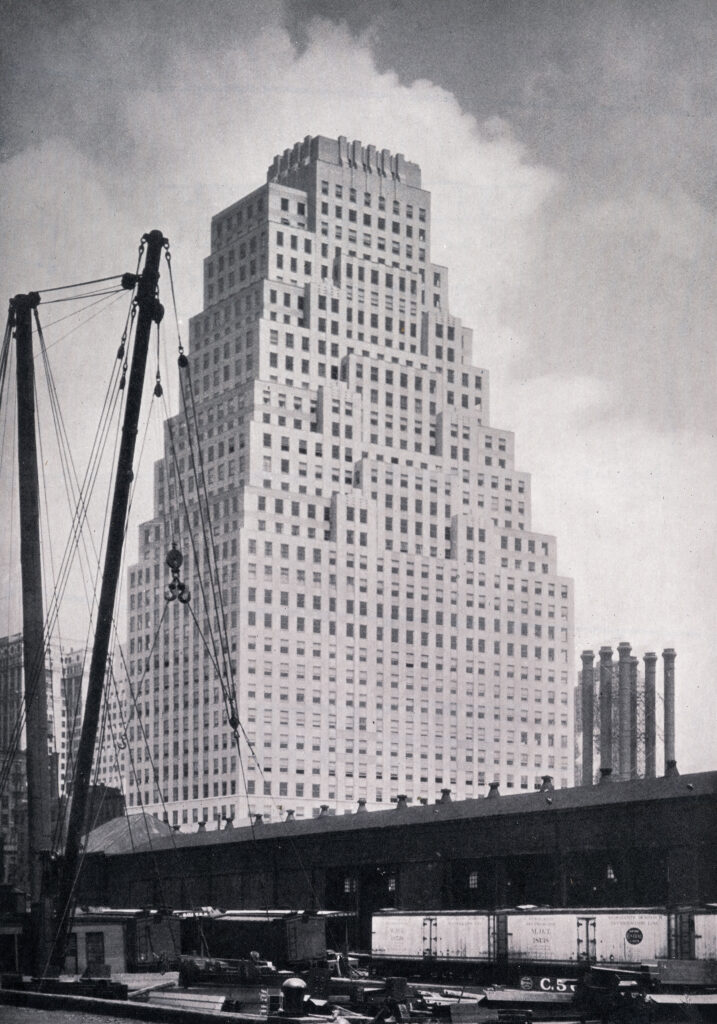

40 Wall Street Construction

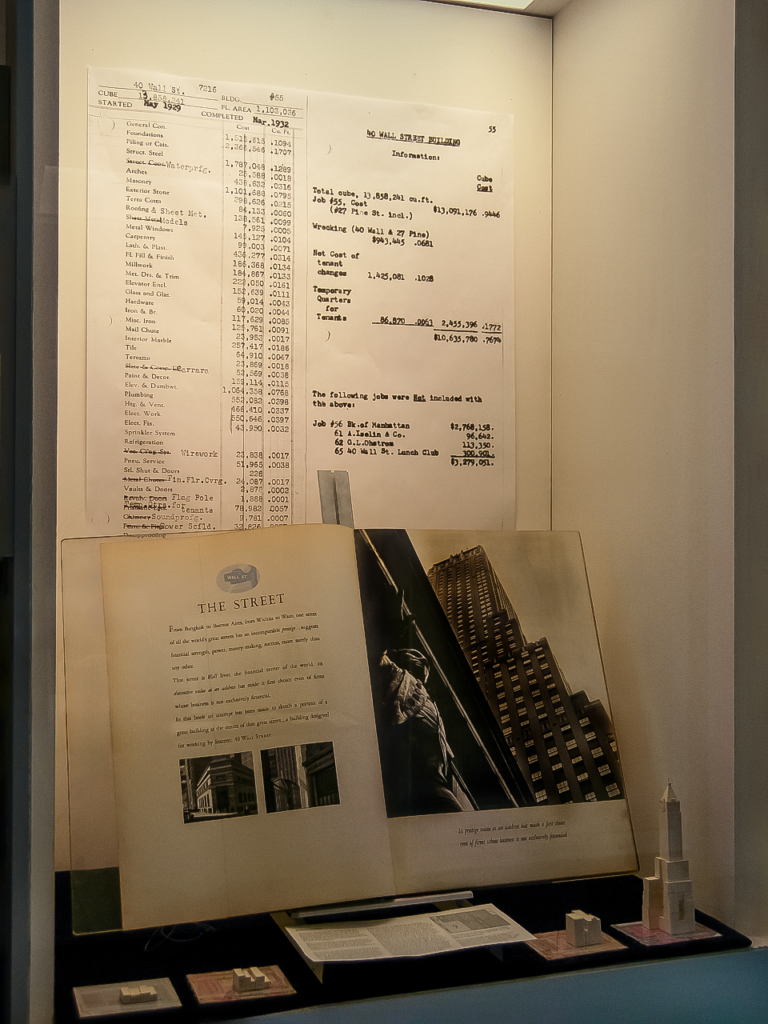

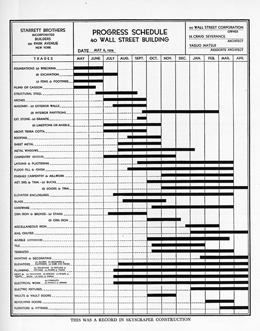

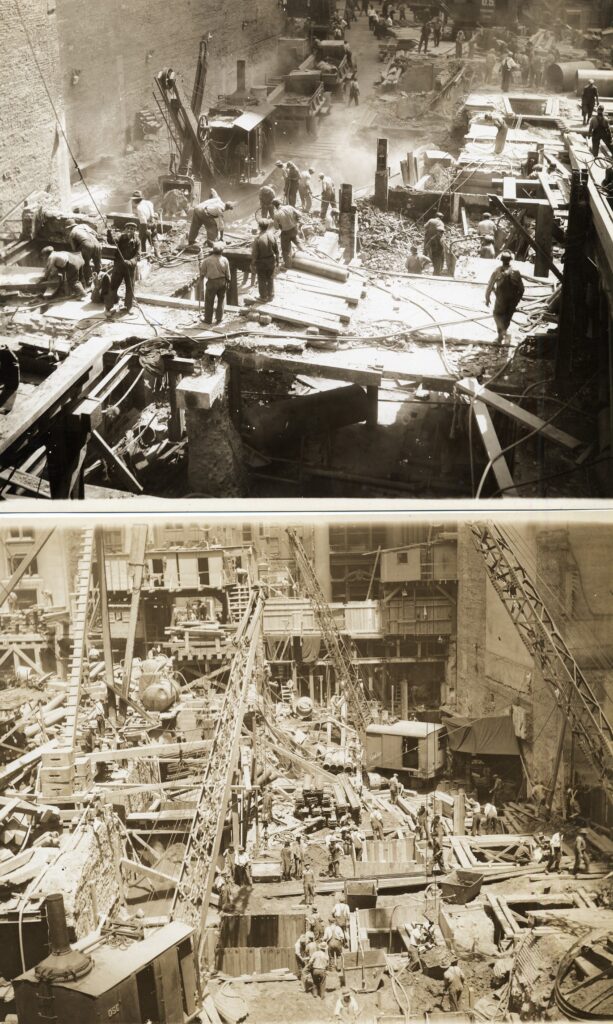

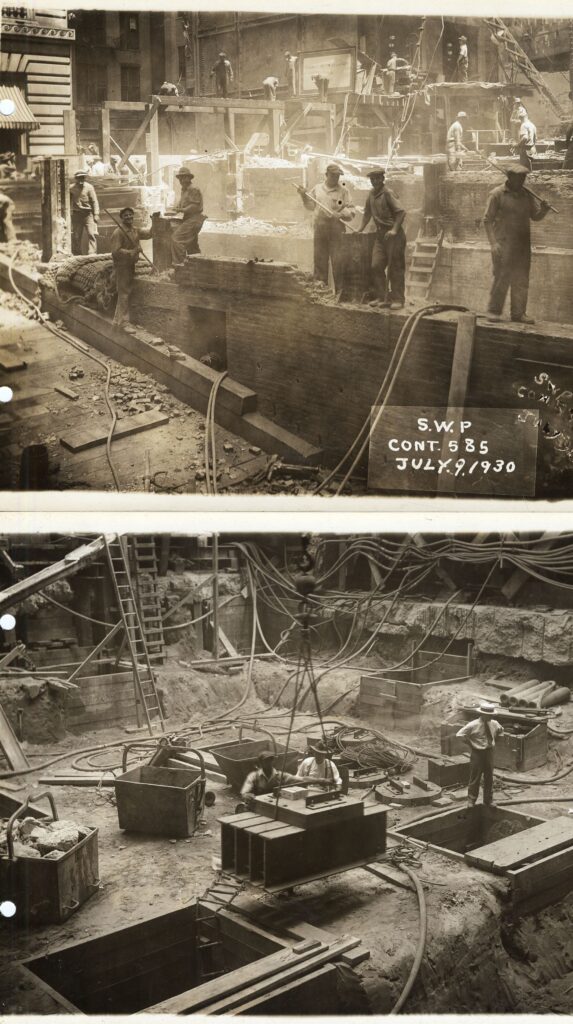

"Of all the construction work I have handled, the Bank of Manhattan was the most complicated and the most difficult, and I regard it as the most successful." So wrote the builder Paul Starrett in his 1938 autobiography Changing the Skyline. In May 1929, just a few months before they received the commission to erect the Empire State Building, Starrett Brothers & Eken constructed the 70-story Bank of Manhattan tower with astonishing speed: demolition and erection was completed in just 12 months.

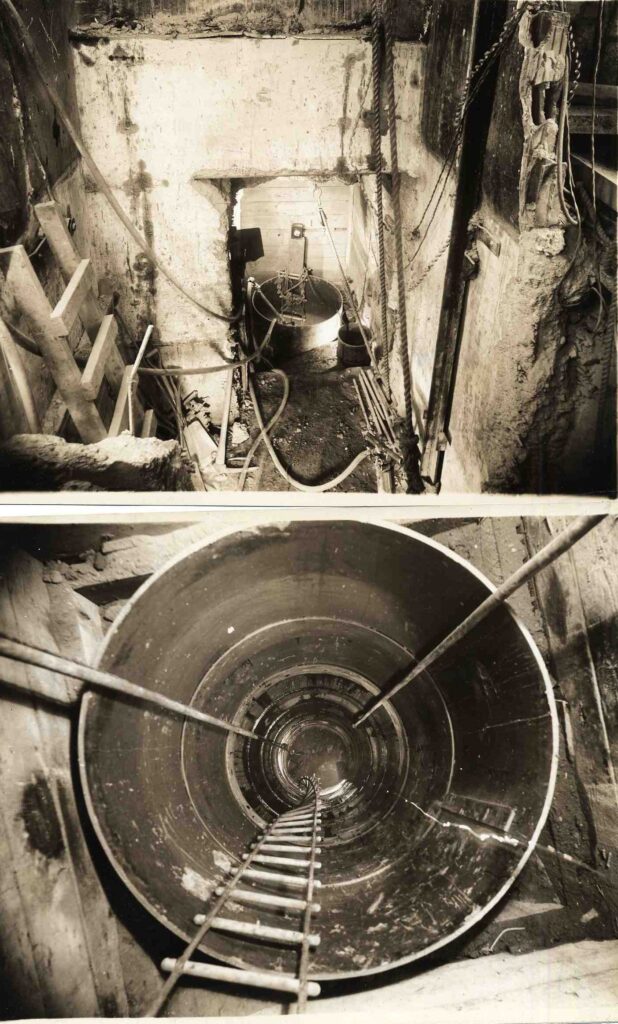

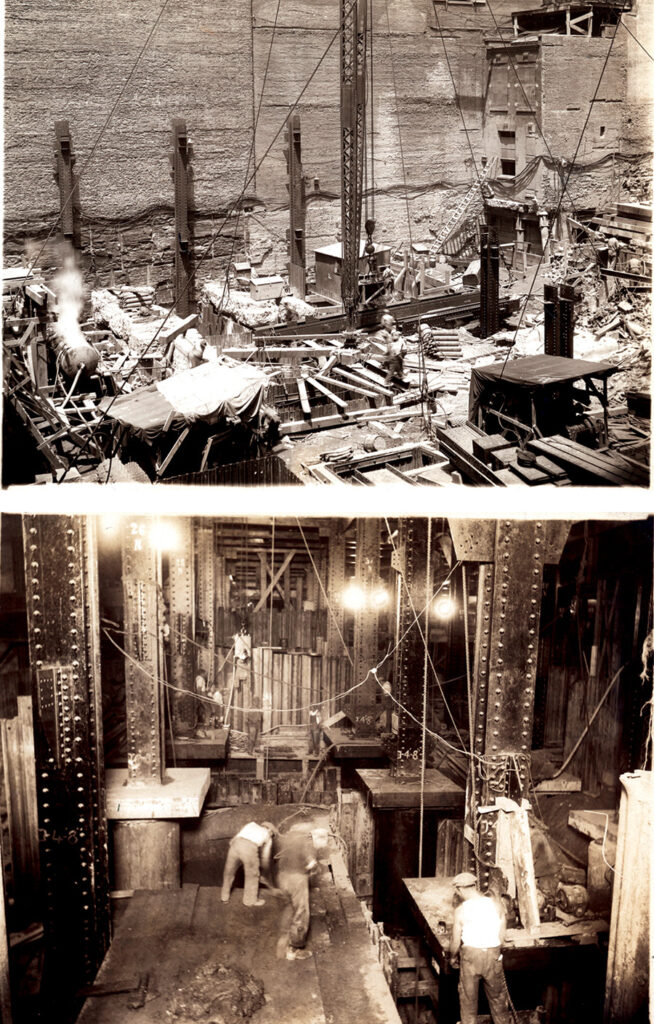

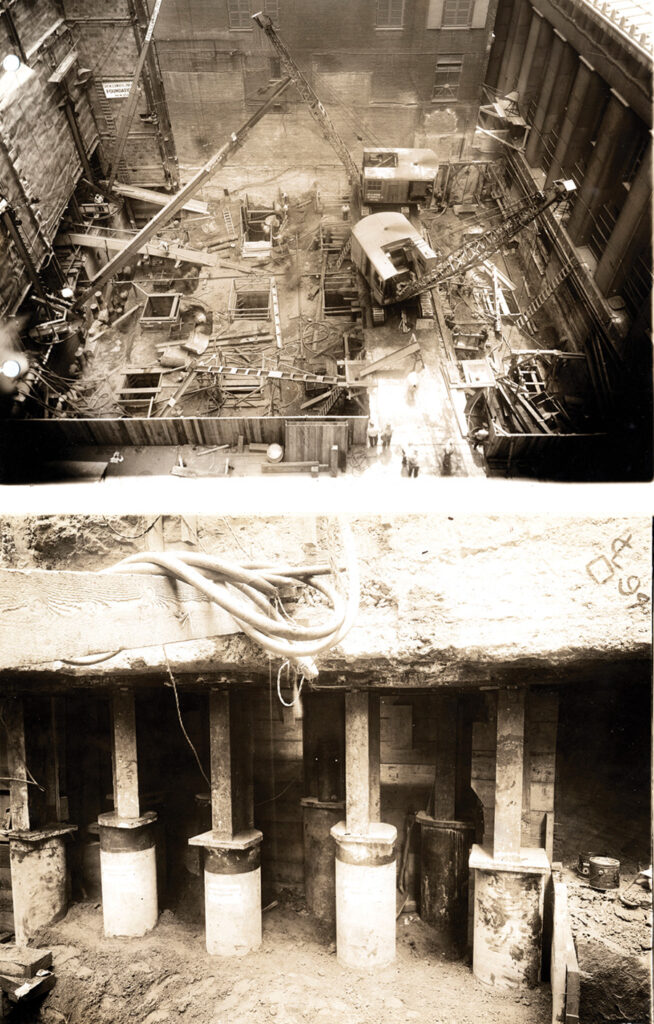

One of the most innovative aspects of the construction was the foundation, fourteen photographs of which are framed on the column on the right. Starrett described the immense challenges of the tight site and construction schedule, which is also graphed in the progress chart to the right.

"The existing buildings were of heavy masonry, with foundation walls five feet thick, in some cases, and very difficult to remove. Obviously, we could not complete on time if we waited on the wrecking. We decided, therefore, to install our caissons under the old buildings, using them to brace and hold our work and to act as a weight against which we could use our jacks. Here the wrecking above was carried on simultaneously with the foundation work below. With three shifts of men working seven days a week, we were able to put tenants in the new offices on May 1, 1930. Our operations were not made easier by the narrow and congested streets, with complete lack of storage space outside the building line. We had to make the most careful plans for delivery and distribution of materials... I had subsequently to answer criticism that we wasted money to save time; our entire expense in overtime was less than one month's gross revenue of the new building, and we saved several months."

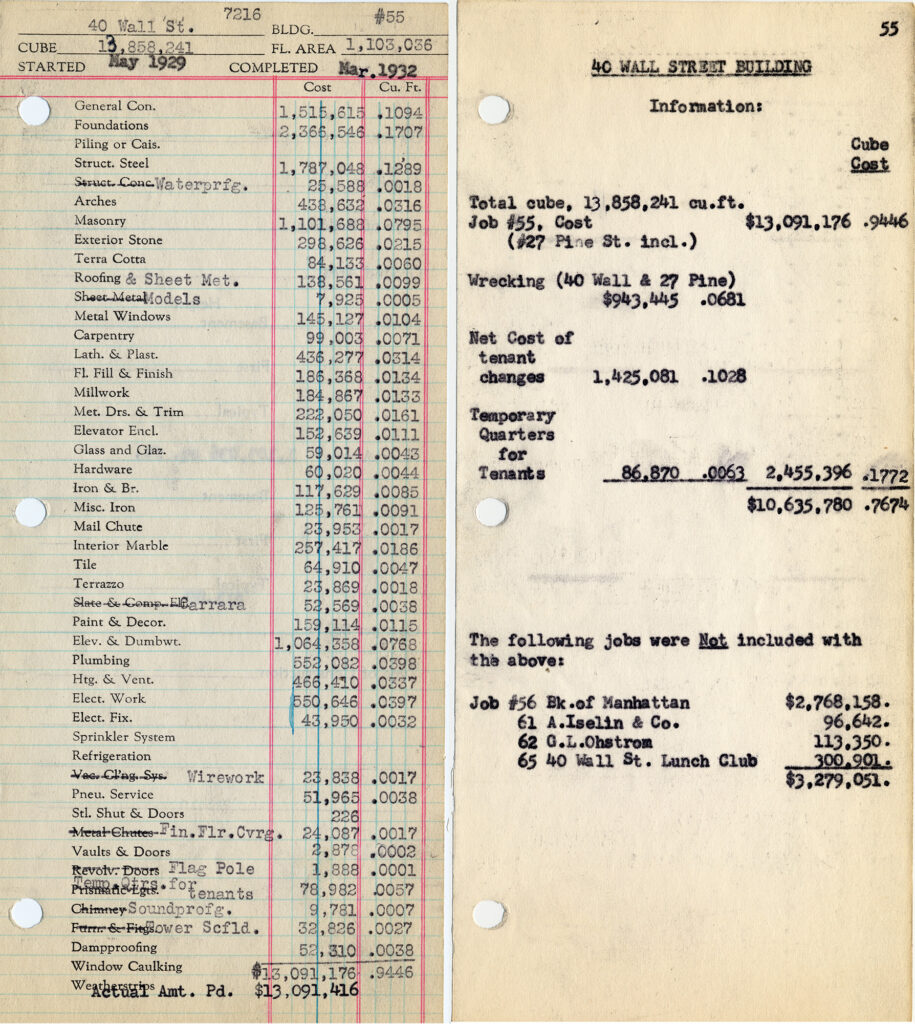

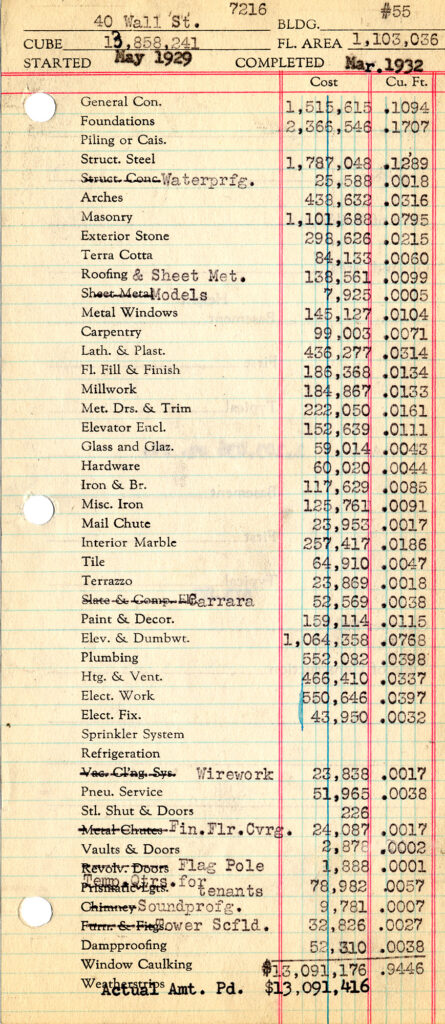

Shown above and in the case opposite are the original Starrett job book and reproduced pages recording precise prices of all the materials used at 40 Wall and 63 Wall. Total cost for the 40 Wall construction was $13,091,416 or 9446 dollars per cubic foot.

Photographs on loan from Mueser Rutledge Consulting Engineers.

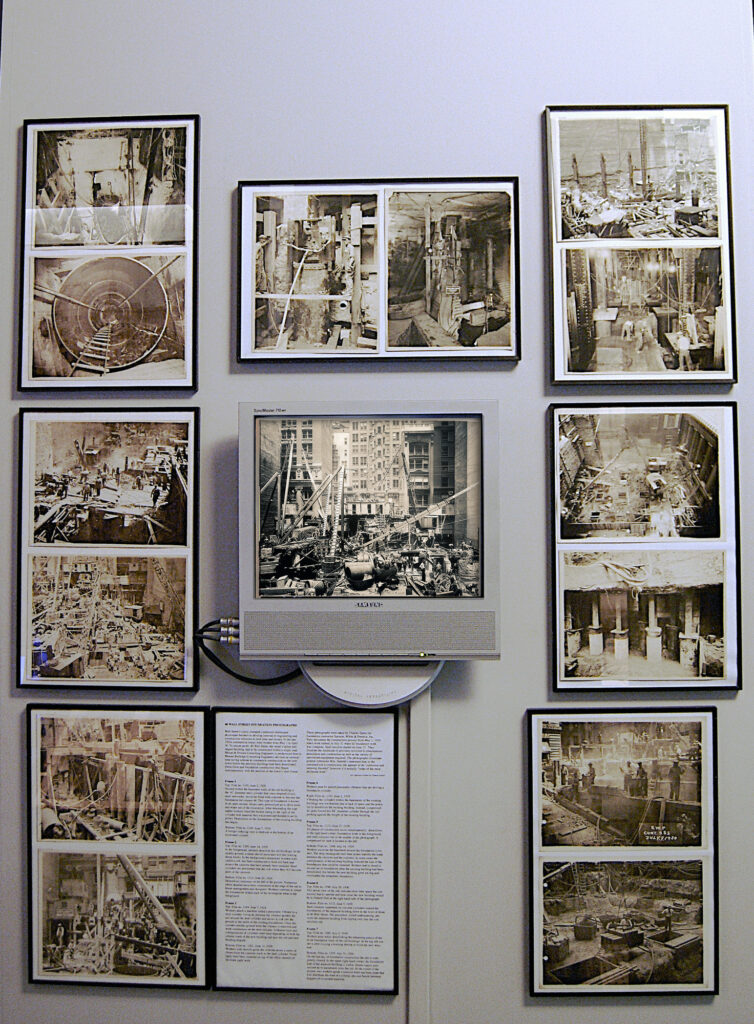

40 Wall Street Foundation Photographs

Wall Street's costly cramped conditions challenged skyscraper builders to develop innovative engineering and construction solutions to save time and money. In the late 1920s commercial leases were written from May 1 to April 30. To ensure profit, 40 Wall Street, the street's tallest and largest building, had to be constructed within a single year. Moran & Proctor Consulting Engineers (a predecessor firm to Mueser Rutledge Consulting Engineers) devised an unusual time saving scheme to commence construction on the new tower before the previous buildings had been demolished. Demolition and foundation construction thus began simultaneously with the erection of the tower's steel frame.

These photographs were taken by Charles Spero for foundation contractor Spencer, White & Prentis, Inc. They document the construction process from May 1, 1929 when work started, to July 31 when all foundation work was complete. Steel erection started on June 17. They illustrate the multitude of activities involved in simultaneous demolition and construction as well as the variety of specialized equipment required. The photographs illuminate general contractor Wm. Starrett's statement that, to the untrained eye a construction site appears to be "confusion and seeming disorder" however it is actually "order of the most deliberate kind."

Top left: Old Bank of New York building, Irving Underhill, 1923; Library of Congress. Top right: North side of Wall Street showing addresses 54-66, University of Oklahoma Archives. Bottom left: Drawing of Bank of New York & Trust Co. Building, courtesy of the Museum of American Finance. Bottom right: Executive office in the Bank of New York, courtesy of the Museum of American Finance.

46 and 52 Wall Street

Wall and William Streets This series of photographs show the successive buildings that stood on the northeast corner of Wall and William streets, a site occupied by the Bank of New York for almost two centuries, from 1796 to 1988. Originally located in a private house at 48 Wall Street, the Bank of New York erected a four-story office edifice in 1858 designed by architects Calvert Vaux & Frederick Clarke Withers. The photograph at the bottom left shows the same building after alterations in 1879 by Vaux & Radford added a story and a mansard roof. At its right stands the elegant little 1873 building by Griffith Thomas built for the U.S. Mortgage Company.

In 1927, the Bank of New York chose society architect Benjamin Wistar Morris to design a new 32-story building on the same narrow site. The limestone-clad setback tower telescoped to a slender spire crowned with a federal eagle, reflecting the bank's eighteenth-century origins, and the executive offices on the floors above employed the same classical style. To its right, at the address 52 Wall Street, rose the slender slab of the National City Company Building, designed by McKim, Mead & White, demolished in the 1980s for the current 60 Wall Street.

The photograph at the lower right captures the row of low-rise buildings of the early twentieth century that survived until the 1970s, to be replaced in the later 1980s by the imposing pile of 60 Wall Street, the model of which shown in this case.

Video: 3rd Ave. El, Produced and Directed by Carson Davidson, Ardee Films, c. 1950. Retrieved from www.archive.org

From 1878 until its demolition in 1955 the Third Avenue Elevated Railroad, or "El," serviced Manhattan's east side, traveling from South Ferry in Lower Manhatatn to the Bronx. This early 1950s film begins with views of Wall Street landmarks, as the film's protagonist, a young journalist, snaps a rattling train crossing the stone-paved thoroughfare at Pearl Street.

Filmed just before the South Ferry - Chatham Square (near the NY County Courthouse) section of the El was closed in 1950, the film records the tight squeeze as the rail lines snake through the office buildings of the financial district. As the train pulls away from the Fulton Street station, the view south shows the white setbacks of the 120 Wall building in the background as the train makes the journey up Pearl Street to the Bowery.

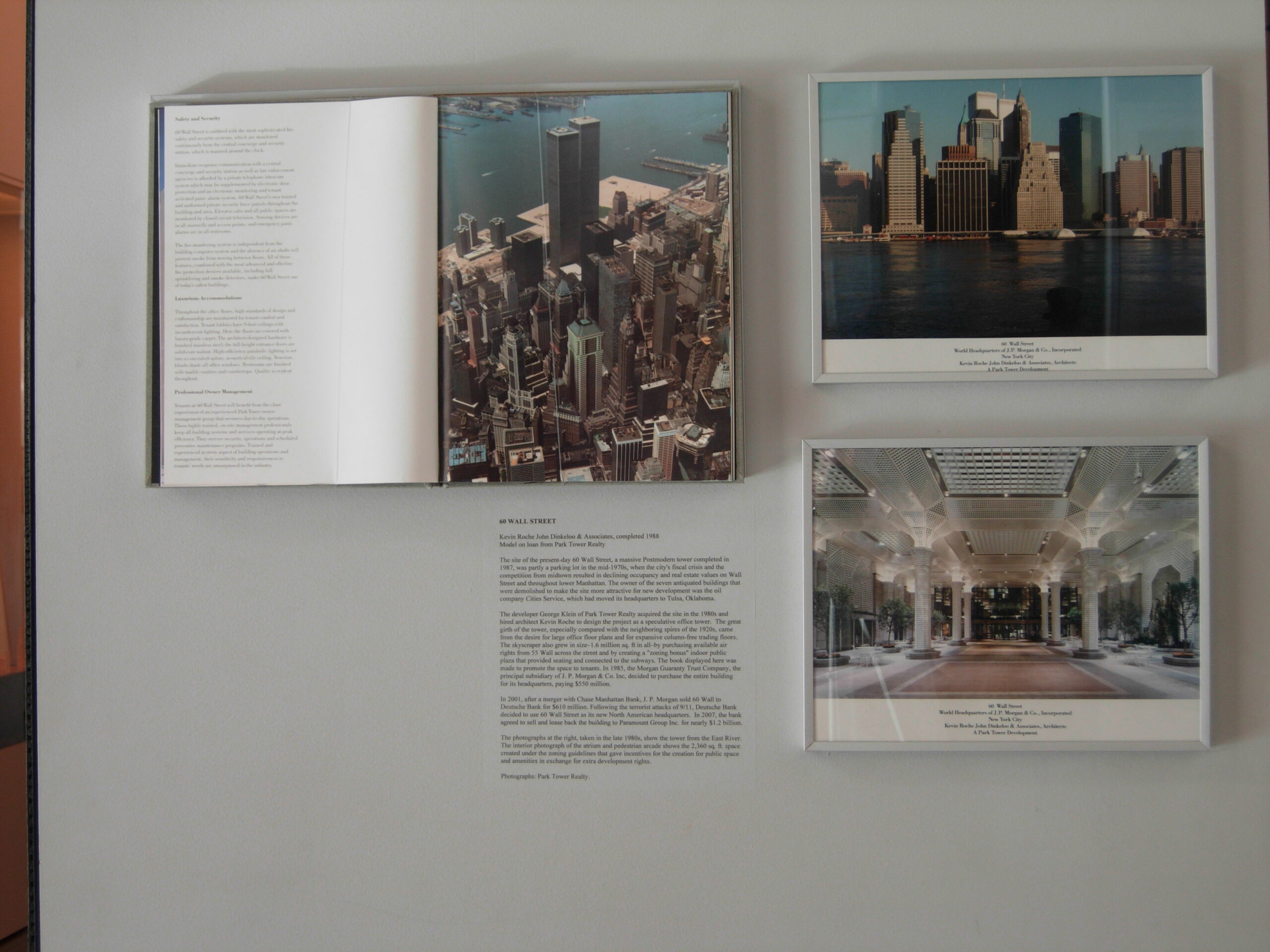

Kevin Roche John Dinkeloo & Associates, completed 1988. Model on loan from Park Tower Realty

Photographs: Park Tower Realty

60 Wall Street

The site of the present-day 60 Wall Street, a massive Postmodern tower completed in 1987, was partly a parking lot in the mid-1970s, when the city's fiscal crisis and the competition from midtown resulted in declining occupancy and real estate values on Wall Street and throughout lower Manhattan. The owner of the seven antiquated buildings that were demolished to make the site more attractive for new development was the oil company Cities Service, which had moved its headquarters to Tulsa, Oklahoma.

The developer George Klein of Park Tower Realty acquired the site in the 1980s and hired architect Kevin Roche to design the project as a speculative office tower. The great girth of the tower, especially compared with the neighboring spires of the 1920s, came from the desire for large office floor plans and for expansive column-free trading floors. The skyscraper also grew in size-- 1.6 million sq. ft in all-- by purchasing available air rights from 55 Wall across the street and by creating a "zoning bonus" indoor public plaza that provided seating and connected to the subways. The book displayed here was made to promote the space to tenants. In 1985, the Morgan Guaranty Trust Company, the principal subsidiary of J. P. Morgan & Co. Inc, decided to purchase the entire building for its headquarters, paying $550 million.

In 2001, after a merger with Chase Manhattan Bank, J. P. Morgan sold 60 Wall to Deutsche Bank for $610 million. Following the terrorist attacks of 9/11, Deutsche Bank decided to use 60 Wall Street as its new North American headquarters. In 2007, the bank agreed to sell and lease back the building to Paramount Group Inc. for nearly $1.2 billion.

The photographs, taken in the late 1980s, show the tower from the East River. The interior photograph of the atrium and pedestrian arcade shows the 2,360 sq. ft. space created under the zoning guidelines that gave incentives for the creation for public space and amenities in exchange for extra development rights.

120 Wall Street

The Berenice Abbott photograph enlarged on the rear of this case was shot from the top of the Irving Trust Company Building at 1 Wall Street on May 4, 1938, and published in her 1939 book Changing New York, a copy of which appears in this case, open to another photograph featuring 120 Wall Street. Abbott, or her collaborator on the text, Elizabeth McCausland, described the architectural forms depicted as both as modern and timeless:

The pyramidal roof of the Bankers Trust Co. Building, derived from classical architecture, is echoed in the modern setback silhouette of 120 Wall Street. In the roof's-eye view of the financial district, serrated roof-lines create a pattern like that of the West's vast canyons, in which soil erosion has carved out abstract sculptures of earth and stone.

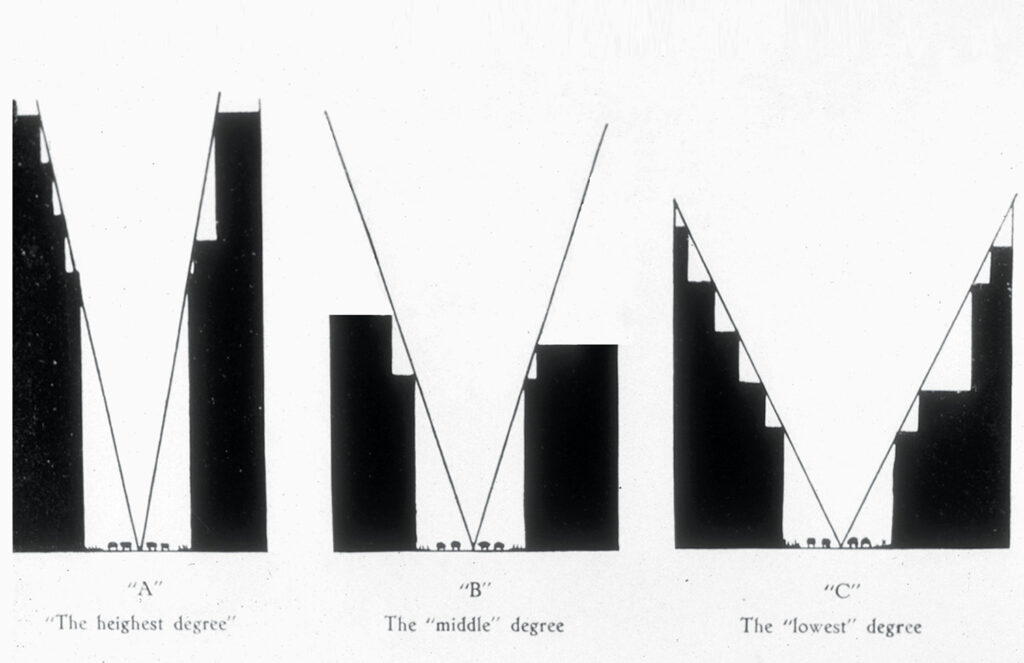

Wall Street slices diagonally through the frame, ending at the East River with the ziggurat of 120 Wall Street. The rental brochure in the front of this case shows the same high-rise as a solitary mountain at the foot of the street, rising from the plain of 19th century counting houses. Completed in 1930, the 33-story skyscraper designed by the Art Deco master Ely Jacques Kahn rose in eight stages and was a precise expression of the template dictated by the city's 1916 zoning law, including the dormer projections.

The influence of the zoning law on New York's skyscraper architecture was profound, producing the setback forms and slender towers that characterized the skyline. Especially in the financial district, where the zoning formulas were most liberal for development, the cliff-like terraces of the shallow setbacks created the stunning canyons of steel and stone.

Mapping Real Estate Value

Given its high land values and strong demand for prime office space, Wall Street was surprisingly slow to give way to skyscrapers. But when the change came, the older structures collapsed as if on a fault line and were replaced by major towers of 50 to 70 stories. This map shows all the high-rises under construction in the financial district in the short span of peak of the 1920s building cycle, 1928 to 1931.

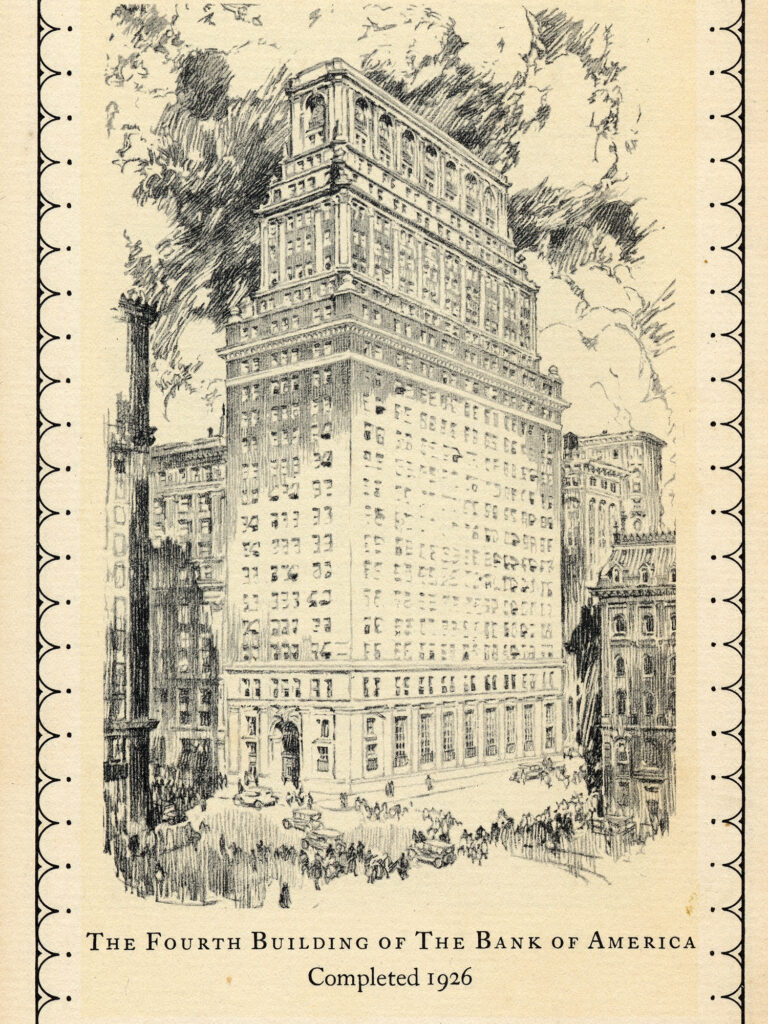

Pictured installed, above, are the major towers of 1928-1931 (clockwise from the top): Bank of America at 44 Wall and the Bank of New York at 48 Wall; 63 Wall; 40 Wall; 1 Wall/ Irving Trust Company; and the Equitable Assurance Company at 15 Broad Street, with an entrance at 35 Wall.

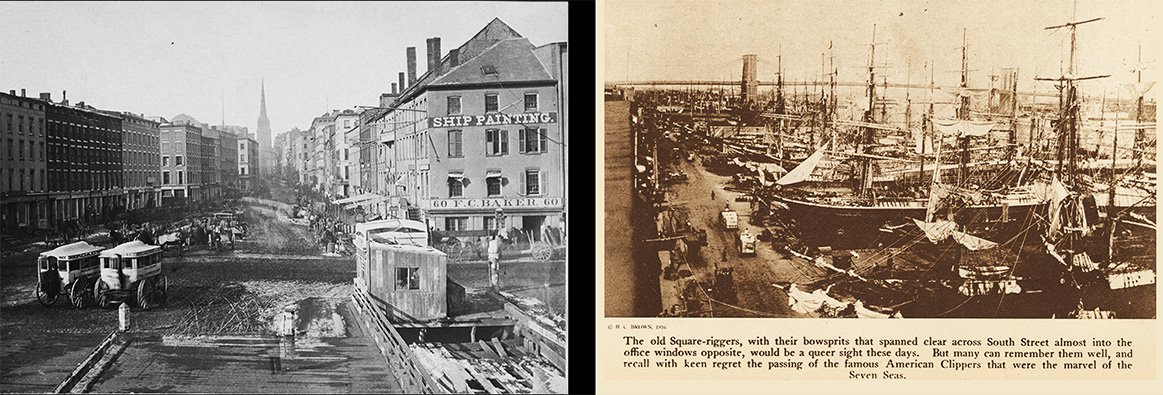

The photograph of the waterfront near Wall and South streets, c. 1860, looks west, with the steeple of Trinity Church looming large at the head of Wall Street. Collection of The Museum of American Finance.

Tall-masted ships, sometimes referred to as "skyscrapers," crowd the shoreline in the 1890s. Reproduced from Valentine's Manual (1916).

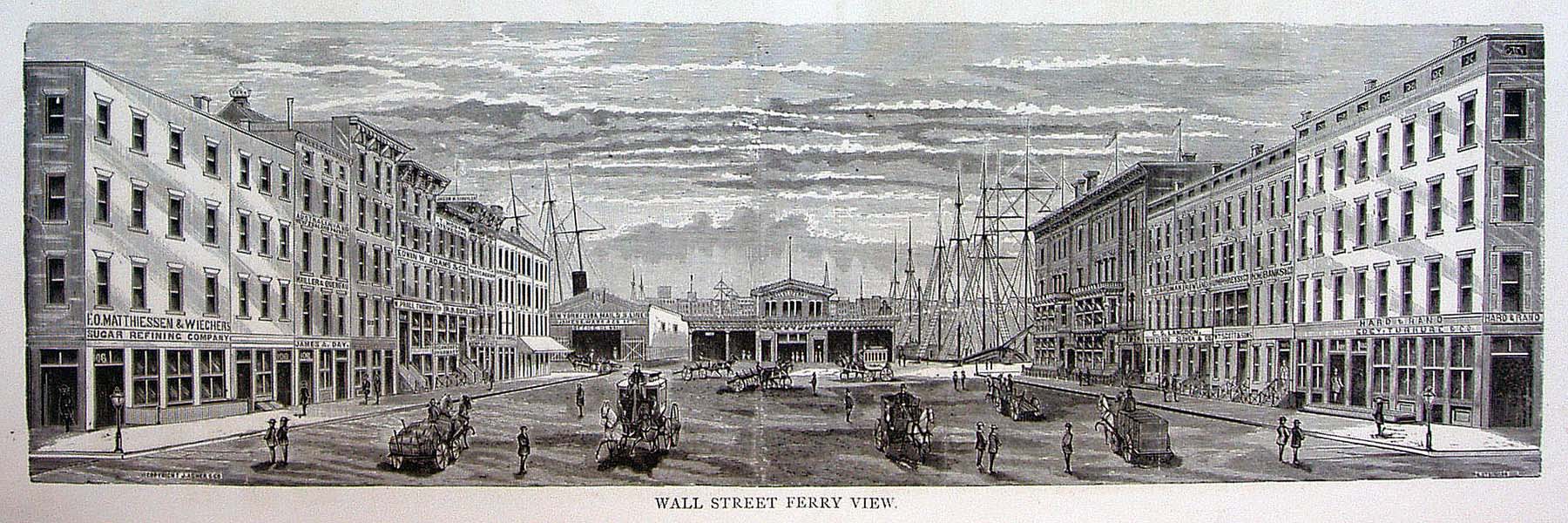

East River End of Wall Street

The shoreline of lower Manhattan has been extended by landfill since the late 17th century, when the port activity of colonial New York was focused on the East River. Wall Street first met the water at Pearl Street, but by 1730, the edge had already advanced to Water Street. By 1780, it extended to Front Street, then to South Street by 1800. The blocks along the waterfront were filled with businesses that served the sailing ships. Merchants traded imported sugar, rum, molasses, lime juice, salt, ginger, cocoa, coffee, and pimento from the West Indies; the region's farms exported flour, butter, and barrels of pickled meat. Goods arriving in New York were often registered at coffee houses, including two of the city's most prominent, the Merchant's Coffee House and the Tontine Coffee House, both on Wall Street; many historians count these exchanges as the predecessors of the New York Stock Exchange.

The photograph, from the collection of The Museum of American Finance, pictures the waterfront near Wall and South streets c. 1860, looking west, with the steeple of Trinity Church looming large at the head of Wall Street. Below, the tall-masted ships, sometimes referred to as "skyscrapers," crowd the shoreline in the 1890s, in an image reproduced from Valentine's Manual(1916).

The Bromley land maps reproduced here, dating from 1879 and 1891, show the waterfront bristling with long finger piers. At the foot of Wall Street in 1879 was the commuter "Ferry to Bay Ridge and Montague, Brooklyn." By 1891, the same dock contained the "West Street Ferry," which was framed by the piers for the NY and Cuba Steam Ship (SS) Co. on the north and the Clyde SS Co. on the south.

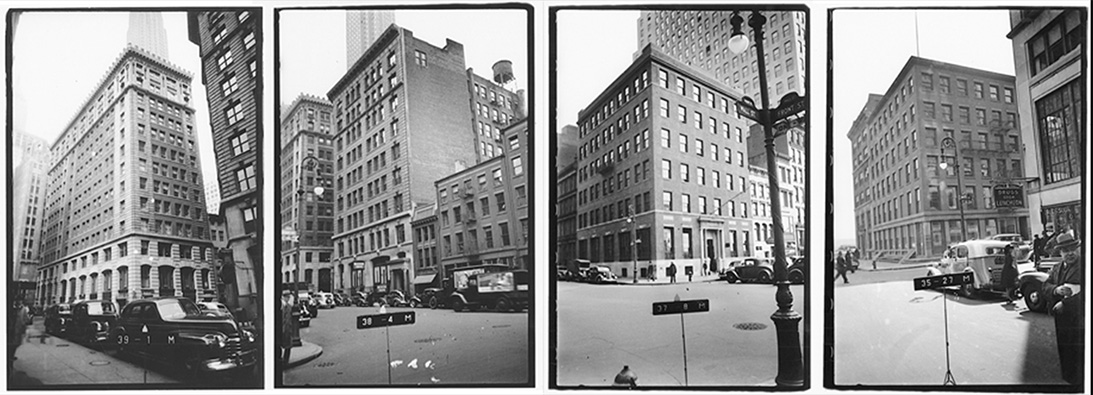

The buildings shown on the left -- from left to right: 82-86 Wall, known as Tontine House, 90-96 Wall, and 106 and 107 Wall-- were photographed in the 1940s as part of the City's program for appraising real property for taxation. Every address in the city was recorded by it block and lot number, as seen in the foreground. The original negatives have been conserved and copied by the NYC Municipal Archives, so new prints, like the ones here, can be viewed and reproduced.