(top) Grand Central Depot, 42nd Street & Vanderbilt Avenue facades, 1884. Collection of The Skyscraper Museum.

(middle) Grand Central Depot train shed, 45th Street & Vanderbilt Avenue facades, 1872. Collection of The Skyscraper Museum.

(bottom) Grand Central Depot, interior, 1872-1900. Library of Congress.

VANDERBILT’S RAILROAD

The first Grand Central, opened in 1871, was built by Cornelius Vanderbilt, one of the richest men in America in the mid-19th century. Having made his first fortune in maritime transport, he began to buy up railroads in the 1850s and in 1863 took control of the Harlem line, the only steam railroad with access to the center of Manhattan. He added the Hudson River Railroad in 1864 and the New York Central Railroad in 1867, consolidating all three into the New York Central and Hudson River Railroad in 1870, thereby creating one of the first giant corporations in United States history.

Originally, the Harlem line had run down Fourth Avenue to a depot at 26th Street. However, in 1859, the New York State legislature banned steam engines south of 42nd Street; the wide cross-town street became the natural location for the new terminal. Vanderbilt began buying more land for the railroad’s ever-expanding operations and soon controlled almost all of the blocks between Madison and Lexington avenues from 42nd to 48th Street. The vast railyards accommodated not just passenger tracks, but freight storage, machine shops, and car sheds. However, the dirty, noxious operations split the east and west sides into two neighborhoods and made passage between them dangerous.

Vanderbilt’s new Grand Central Depot on 42nd Street faced the city to the south with a monumental presence, towering above the surrounding low-rise and still largely residential districts. Architect John Snook, who had designed the Vanderbilt mansion on Fifth Avenue, and engineer Isaac Buckhout fashioned a 42nd Street facade that followed contemporary French models, with three mansard-roofed towers that served the three different lines: the New York Central & Hudson; the New York & Harlem; and the New York & New Haven. The longer L-shaped wing, stretching nearly 700 ft (213 m) along the newly-created Vanderbilt Avenue to 45th Street, contained passenger services such as waiting rooms, ticket offices, and restaurants.

Almost completely disguised behind the imposing architecture was the engineering marvel of the train shed, a vast wrought iron and glass canopy modeled on London’s great St. Pancras Station, but exceeding it in length and span. Brooklyn architect and engineer R. G. Hatfield designed the structure that was carried on 32 wrought iron trusses that spanned 200 ft (60 m) and arched to a height of 100 ft (30 m). The shed was 652 ft (199 m) long and enclosed twelve tracks and seven platforms. This scale made the Grand Central Depot the largest rail facility in the world.

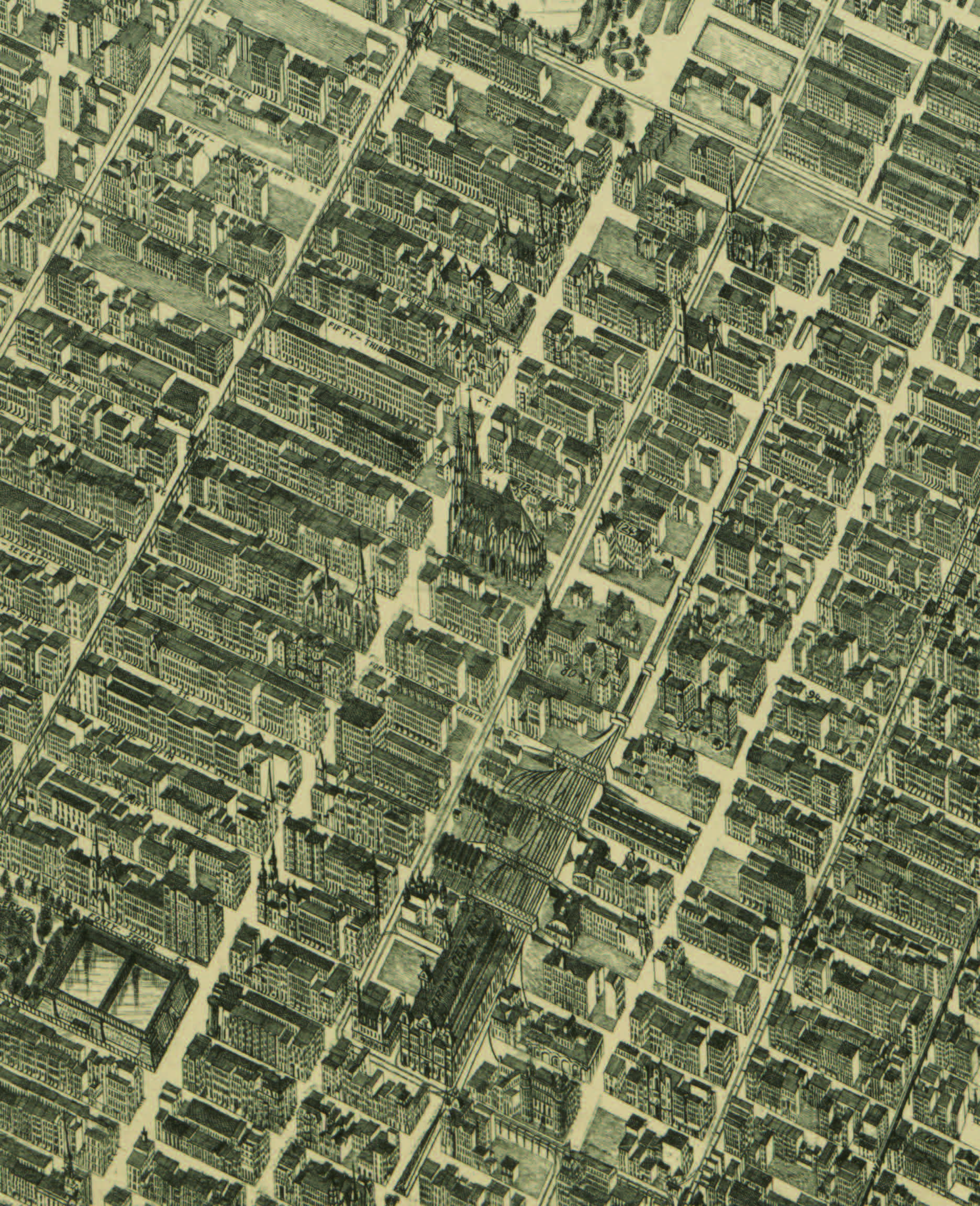

Close-up of the Taylor Map of New York by Will L. Taylor for Galt & Hoy, 1879. Library of Congress.

NEW YORK IN 1879

The enlarged detail of the extraordinary 1879 Taylor Map of New York, a bird’s-eye view of the whole of Manhattan island, focuses on the area around Grand Central Depot from 41st to 57th Street and shows the development of the territory around Vanderbilt’s new station at the end of its first decade. At the time, the population of Manhattan was about 1.1 million people and growing quickly through immigration. On the east side of Central Park, development had nearly overspread the island, although above the Sixties the blocks were less densely populated.

At the bottom center of the image is Grand Central and its railyards, which fan out from Fourth Avenue to Madison and stretch to 49th Street. From there, four tracks continue north in a shallow open cut with bridges at some streets. The tracks disappear into the tunnel at 56th Street, where Fourth Avenue becomes a wide road separated into two lanes by a mall. The mall was not open to pedestrians as it accommodated steam to escape through the tunnel’s vents. Other forms of mass transit can be seen on Madison Avenue, where a horse-drawn street car traveled north from 42nd Street, and on Third and Second Avenue, where two elevated railways connected South Ferry to Harlem.

In 1879, St. Patrick’s Cathedral dominates the block near the center of the image and other churches and residential buildings characterize Fifth Avenue, which in the era was the prime residential vector for wealthy New Yorkers. Soon, however, the pressures of urban growth would overtake the district as the growing population crowded onto all vacant lots and new technologies allowed buildings to rise taller. The New York Central necessarily added more trains, including suburban lines that served an ever-growing number of commuters as Grand Central began to recenter the City’s business activity around this powerful hub.

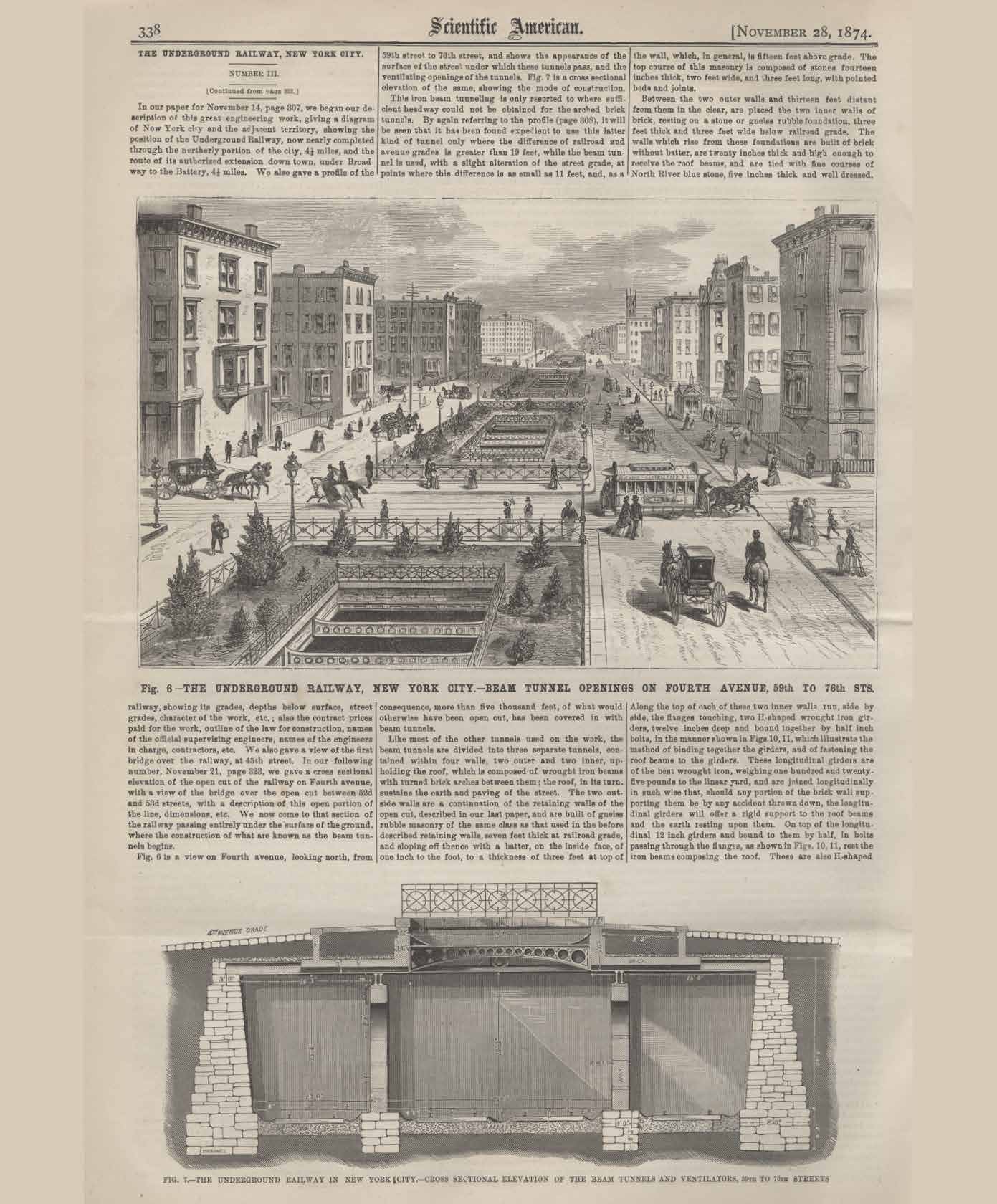

“The Extraordinary Railway, New York City,” Scientific American 31, no. 22 (1874): 338. Collection of The Skyscraper Museum.

THE FOURTH AVENUE IMPROVEMENT PROJECT

In 1872, less than a year after Cornelius Vanderbilt opened the new Grand Central Depot, the New York State Legislature passed a law requiring the 4.25 miles of the New York Central’s tracks from Grand Central north to the Harlem River to be placed below grade. The legislation came in response to public and press outcry about fatalities at grade-level crossings north of the depot, which The New York Times called the city’s “most fearful death-trap.”

The Fourth Avenue Improvement Project began in 1872 with the work paid for and performed by the Central, with the City contributing to the cost of the cross-street bridges. Before this, the tracks ran at grade from 42nd to 68th Street, while from 68th to 96th, due to a rise in terrain, they ran in an open rock-cut tunnel.

The Improvement Project transformed the northern section of Fourth Avenue, making it more conducive to residential development. The tracks were buried entirely below ground by constructing “beam tunnels” from 56th to 67th Street and from 71st to 80th Street. Made of wrought iron beams with brick arches, these tunnels were constructed using four masonry walls that divided the tunnel into three sections and supported both the roof and the street above. A drawing in Scientific American, dated November 28, 1874, pictured the cross-section of the structure with the open vents protected by ornamental ironwork. The result was to be a future, gracious boulevard with a central landscaped mall that disguised the smoke vents for the steam locomotives. Originally closed to pedestrians, these malls, in the early-20th century, would be opened with footpaths and benches.

(top) Grand Central Station, 42nd Street & Vanderbilt Ave. facades, c. 1900. Courtesy of the New York Public Library.

(bottom) Grand Central Station, train shed interior, c.1900. Courtesy of the New York Public Library.

RENOVATION: GRAND CENTRAL STATION

In 1896, twenty-five years after Grand Central Depot opened, it could no longer efficiently serve the growing demands of New York. The city’s population had increased from just under a million in 1870 to 1.5 million in 1890, and railroad traffic had quadrupled. The Depot’s fifteen tracks were unable to handle the pace of growth and the Railway Gazette reported that the crowded and complicated conditions in the yard led to frequent employee injuries.

The New York Central had added an annex of seven tracks and five platforms in 1885, expanding on the east side across the newly created Depew Place. Further expansion called for an almost entirely new building. In 1898, New York architect Bradford Lee Gilbert, a specialist in railroad stations who had recently completed the Illinois Central Station in Chicago, was hired to work alongside the railroad’s chief engineer, William Katte. By 1899, Grand Central stood three stories taller, and its exterior was transformed into a neo-Renaissance block crowned with four cupolas. The remodeled building was renamed Grand Central Station and featured modern upgrades including elevators and electric lighting.

In October 1899, construction began on additional changes to the interior by Philadelphia architect Samuel Huckle, Jr., working with the railroad’s new chief engineer, William J. Wilgus, the man who would become the mastermind of the next, decisive reinvention of Grand Central. Huckle and Wilgus combined the building’s three separate waiting rooms into a grand hall and added even more tracks to the shed. They also brought the station’s technology into the 20th century by implementing a pneumatic interlocking system and modern switching devices.

(top) The first electric train leaving Grand Central, with William J. Wilgus at the controls, 1906. Collection of The Skyscraper Museum. Gift of Andrew Alpern.

(bottom) Letters by William J. Wilgus to railroad President William H. Newman in 1902 and 1903. Courtesy of the New York Public Library.

Grand Central train yard looking north-west from 44th Street, 1904. Courtesy of the National Museum of American History.

WILLIAM J. WILGUS & ELECTRIFICATION

Despite the many improvements to Grand Central, one primary issue remained: the noisy, dirty, and dangerous steam locomotives themselves. As the New-York Tribune reported in July 1901, “The thousands who daily travel through the Park-ave. tunnel... are the victims of unspeakable tortures.” Predictions of disaster were realized on January 8, 1902, when a morning commuter train overran signals in the smoky tunnel beneath 56th Street and rear-ended a halted train on the same track, killing seventeen and injuring scores. The public outrage was extreme, and a week later, the New York Central announced a plan to electrify its system and place all tracks into the station underground. In 1903, the New York State Legislature banned steam locomotives in the city, setting a deadline of July 1, 1908.

The electrification plan could be adopted quickly because the Central’s chief engineer, William J. Wilgus, had been advocating for a change to electric power since 1899. Other cities had demonstrated the advantages of using electrification; in Paris, at the Gare d’Orsay, the station was placed underground and a hotel was developed above. Executives of the Central, however, resisted the expense of such plans for their enormous railyard – until they had no option.

Wilgus prepared a new plan that he proposed in two successive letters to the President of the railroad, William H. Newman, in December 1902 and March 1903. In three succinct pages, he laid out both a technical solution to expanding capacity by electrifying the trains and double-decking the tracks, as well as an economic strategy to fund the vast expenditure: the concept of “air rights.”

The photograph shows the rail yard in November 1904, before the implementation of Wilgus’s plan to depress and double-deck the tracks. The view looking north captures the great expanse of the 70-acre, fan-shaped area. Long, narrow truss bridges carry the cross streets from Lexington to Madison Avenue. The edge of the train shed can be seen on the left and the steam of locomotives billows on the right. The photo also makes clear how neighborhoods were built up to the edge of the yards. In the distance, the skyline shows the twin spires of St. Patrick’s Cathedral and, at center, the new high-rise hotels on Fifth Avenue and 55th Street, the Gotham and St. Regis. A publicity photograph of Wilgus operating the first electric locomotive leaving Grand Central in 1906 is seen on the right.

(top) Reed & Stem’s proposal for the terminal building and the Court of Honor, 1903. Collection of The Skyscraper Museum. Gift of Andrew Alpern.

(bottom) Samuel Huckel’s proposal for Grand Central Terminal, showing the tracks below the streets to the north, 1903. Collection of The Skyscraper Museum. Gift of Andrew Alpern.

A MASTER PLAN FOR THE SITE

By 1903, Wilgus’s plans for the electrification of Grand Central were fully accepted and he had been elevated from Chief Engineer to Fifth Vice President of the New York Central. Now, it was time to determine the architectural scheme for the new building and an overall master plan for the immense 70-acre site. Four firms were invited by the New York Central to submit proposals. Two were obvious choices: the celebrated Chicago architect and planner Daniel H. Burnham, who in 1901 had led the McMillan Plan for Washington, D.C. and Union Station; and New York’s patrician firm McKim, Mead & White, then in the midst of building the great Pennsylvania Station on Manhattan’s West Side. The other two contenders, far less famous, were experienced designers of railroad terminals: the Philadelphian Samuel Huckel, Jr., who had recently worked with Wilgus to remodel the interior of Grand Central Station in 1899; and Reed & Stem of St. Paul, Minnesota. It did not hurt that Charles Reed was Wilgus’s brother-in-law. The latter two firms’ proposals are illustrated here.

Reed & Stem won the commission, at least initially. Their success was due in large part to their understanding of Wilgus’s priorities of a seamless flow of levels of passengers, trains, and city traffic, as well as the development of air rights. Their proposal, described in the top drawing, features an 18-story high-rise above the station and a “Court of Honor” over the tracks, which can be seen at the bottom of the drawing in a cross-section. Around the formal civic space and station, the north-south city traffic would be restored.

In the bottom scheme by Samuel Huckel, the office building and hotel seem shoe-horned onto the block and Park Avenue tunnels straight through the structure. The emphasis in Huckel’s view is entirely on the rail yard and creating the platforms for streets as a way of delineating the areas of “air rights” for the future building sites.

The idea of transforming the area north of the terminal building into a grand civic space with harmonious facades and a uniform cornice line remained popular during the decade-long construction. Renderings of the future Grand Central conformed to the aesthetic of the City Beautiful movement even as the terminal opened in 1913 and the blocks north of 44th Street were undeveloped. Eventually, the elevated circumferential roadways that carried Park Avenue around the station, which had been essential to the original Wilgus and Reed & Stem plan, were realized with the construction of the bridge over 42nd Street that connected the north and south sections of the avenue.

Grand Central Yards from 47th Street during the early stages of excavation, Ewing Galloway, 1907. Courtesy of the New York Public Library.

THE WORK ON THE YARDS AND PARK AVENUE

Work began in earnest in the summer of 1903 now that a master plan had been chosen. Wilgus, a meticulous manager, devised an excavation and construction plan that would not interfere with scheduled service at the terminal. From 42nd to 49th Street, the work was divided into three longitudinal bites to be completed one by one from east to west. The 1909 photograph of the railyard and old terminal at around 45th Street makes clear the titanic scale of the construction. On the east, bite one has been excavated to a depth of about 60 feet. Workers traverse the different levels while train cars use remaining tracks to haul away earth and stone. By the end of construction, more than 3 million cubic yards of dirt and rock would be excavated. Meanwhile, on the west side, passenger trains still make use of the tracks into the terminal.

The expansion of capacity north of the railyard also necessitated work on the city streets from 49th Street to 56th Street where trains emerged from the tunnels. Because the New York Central was a private corporation using the space of public streets, it needed legislation passed by both the State and City to build below the public right-of-way of Park Avenue, which they received in 1903. The railroad also purchased more land fronting these uptown blocks.

(top) Park Avenue looking north from 50th Street, 1890. Courtesy of New York Transit Museum.

(bottom) Park Avenue looking north from 50th Street, 1906. Courtesy of the National Museum of American History.

The two photographs show the process of transformation from the depressed rock-cut tracks with crosstown bridges to the new at-grade Park Avenue. In the top photo from 1890, on the east (right) side, the buildings are mostly industrial: the Steinway piano factory, built in 1860, occupied the block between 52nd and 53rd Street, and the Schaefer Brewery stood just to its south. The two parts of Fourth Avenue on either side of the tracks served carts, horse-drawn carriages, and pedestrians; buildings filled all the lots.

The bottom photograph shows the same blocks under construction in 1906, where on the east side the process of double-decking has begun. At 53rd Street, the tracks began the standard 2 percent rate of descent into the lower level of the terminal. The number of tracks in the tunnel was also increased from four to ten. As a result, Park Avenue widened to 140 ft (43 m), compared with the 100 ft (30 m) width of Madison Avenue. On completion, this section of Park Avenue partially opened to street traffic, but the full breadth of the railyards from 44th to 49th Street remained under construction for several years, even after the terminal’s completion in 1913.

New York Central Mortgage Bond certificate, 1913. Collection of The 1913 Stock Certificate NYCHR RR. Courtesy of George LaBarre Galleries, Inc. www.glabarre.com. Collection of The Skyscraper Museum.

FINANCING AND AIR RIGHTS

Beyond the brilliant engineering of the double-decking of the railyard and terminal and sequencing of the construction, Wilgus conceived of a financial blueprint to balance the vast expense of the work with new revenue. Key to his plan was the concept of “air rights” – a term that today is fundamental to development in Manhattan, but was then entirely new. The New York Central would develop commercial buildings above the tracks or lease the rights to others. As Wilgus explained, this plan would allow the Central to “earn an income sufficient to pay the interest, not only of the cost of the terminal itself, but also on the other improvements in New York City and vicinity, including our electrification schemes.” He projected a net profit from the real estate development of 10 percent. From this, the idea for a Terminal City was born.

The Board of Directors of the New York Central adopted the plan to electrify the tracks into Grand Central in 1902, just a week after the fatal tunnel accident, and authorized a $35 million increase in the company’s stock to finance the work. Ultimately, that sum would in no way cover the escalating construction costs which rose from Wilgus’s first estimate of $40.7 million to $71.8 million by 1906. The railroad issued mortgage bonds like the one on the left, which promised reliable interest of 4.5 percent. Funds raised from the mortgage bonds would be used for the entire terminal complex: station, tracks, and Terminal City. A separate subsidiary, the New York Central Realty Company, sold its own mortgage bonds to finance their commercial properties.

Diagram and map of Grand Central’s new track system from “Grand Central Development Seen as Great Civic Center,” Engineering News-Record 85, no. 11 (1920): 496-504. Part of a series of articles that sought to clarify the key concepts of the original Wilgus plans.

The multilayered operations of the double-decked terminal complex are described in the richly informative diagram on the left. A key feature of Wilgus’s plan was the loop tracks, which allowed some trains to exit engine-first around the station, greatly improving train flow and capacity. In another major improvement, incoming and outgoing travellers could now be separated. Within the terminal, ramped passageways made movement between levels fluid. The cross sections of the terminal, tracks, and connections to the neighboring hotels in the upper right of the drawing make clear the vast underground network of connections.

(top) Color rendering of the idealized Grand Central Terminal and Terminal City, with Wilgus’ hand-written notes (added later), c. 1910. Courtesy of the New York Public Library.

(bottom) Section drawing of Grand Central Terminal showing the concourses, ramps, and platforms, from “Monumental Gateway to a Great City,” Scientific American 107, no. 23 (1912): 484-489.

WHITNEY WARREN’S GRAND CENTRAL

Reed and Stem had won the commission for Grand Central Terminal due to their alignment with the key points of Wilgus’s engineering plans, but other forces soon came into play. Whitney Warren, an architect of pedigree by class – he was a cousin and friend of William K. Vanderbilt, grandson of Cornelius and the current chairman of the New York Central – as well as by his training at the Ecole des Beaux Arts, maneuvered a role in designing the architectural image of the terminal. Vanderbilt used his powers to add the partners Warren & Wetmore to the project team. In February 1904, the two firms signed a contract with the Central forming the Associated Architects.

The relationship was tense throughout their partnership, especially because Warren quickly began to completely rework the Reed and Stem design. He eliminated the elevated roadway and office tower in his design, which he conceived as a classical three-bay triumphal arch and gateway to the city. When Wilgus unexpectedly resigned from his position in 1907, Reed’s power to influence the planning declined dramatically. In the end, Reed and Stem’s plans for an elevated road were reinstituted, as were the Wilgus-Reed insistence on ramps rather than stairs to connect the multiple levels of the terminals in a continuous flow. Indeed, these became a widely praised hallmark of the design. The glory of Grand Central is, of course, the Grand Concourse. Upon the terminal’s completion in 1913, it was the largest concourse in the world at 120 ft (37 m) wide, 275 ft (84 m) long, and 125 ft (38 m) tall. The dazzling constellation mural on the ceiling was painted by Warren’s friend and accomplished French painter Paul Cesar Helleu.

Charles Reed died unexpectedly in December 1911, before the terminal was finished. Wetmore quickly and secretly entered into a new contract with the Central that made the Warren & Wetmore firm the sole designers for Grand Central. While a lawsuit by Allen Stem and the Reed estate that demanded payment for the work performed eventually prevailed, in general, in the eyes of history, Whitney Warren has been called the architect of Grand Central. And beyond the station design, the Warren & Wetmore firm came to design the majority of the buildings in the Terminal City complex.

View south of 50th Street of Grand Central Terminal, 1913, Box 8, Folder 6, Grand Central Terminal Collection, Drawings and Archives, Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University.

BUILDING TERMINAL CITY

Grand Central Terminal opened to the public on February 2, 1913, with the New York Times proclaiming, “the new station has risen amid the wreckage of the old.” North of the station, though, wreckage remained. The extraordinary photograph of June 1913 on the left shows block-sized voids in the platform that will become Park Avenue. Below, on the left, tracks can be seen, while on the right the last section of the below-grade construction is still underway. On the future avenue temporary workers’ structures line the median. In the distance, the massive Biltmore Hotel, which would open in December 1913, is still under construction.

(top) Park Avenue & Terminal City looking north from 45th Street, 1917. Courtesy of the National Museum of American History.

(bottom) Terminal City buildings looking southwest from 50th Street, 1917. Courtesy of the National Museum of American History.

In the blue cyanotype photographs, dating from 1917, new buildings begin to fill in the blocks above the tracks. In the top image, which looks north beyond the still empty sites, on the left are the twin buildings of the Marguery Hotel & Apartments. Across the avenue and two blocks north, the industrial structure of the railroad’s powerhouse occupies part of the site of the future Waldorf Astoria, between 49th and 50th Street. This plant generated both electric and steam power, not only for the terminal and its trains, but also to serve the buildings developed on the air rights lots.

In the lower cyanotype, which looks southwest from 50th Street on October 3, 1917, pedestrians stroll the brand new boulevard to view Warren & Wetmore’s Marguery Hotel, nearing completion, and the same firm’s Hotel Chatham, completed in 1916, one block north. The 12-story Marguery occupied a full-block site that stretched from Park to Madison Avenue between 47th and 48th Street. As a residential building, the palazzo-like blocks were constructed around an immense 275-foot courtyard called the Italian Garden, and the complex was bisected by a gated drive that was really a continuation of Vanderbilt Avenue. Developed by the successful Upper West Side builder Joseph Paterno, the Marguery was designed to attract New York high society. The mansion-like apartments of six to ten rooms took the address 270 Park Avenue and quickly filled with tycoons and socialites. Their dinners, teas, and debutante balls kept the Marguery Hotel’s posh restaurants and ballroom booked.

By the mid-1940s, though, the large site and low-rise structures had attracted the interest of the next generation of developers of office towers. After several failed plans, in 1957, the Marguery was demolished for the 52-story SOM-designed headquarters for Union Carbide. That tower was demolished in 2019 and today the new Foster + Partners’ skyscraper for JPMorgan Chase rises nearly 1400-foot on the same site.

(top) View of the Grand Central Terminal and the surrounding area, Fair Child Aerial Survey, 1923. Courtesy of the New York State Archives.

(bottom) Park Avenue, south from 51st Street, 1932. Courtesy of the New York Public Library.

A NEW SCALE: SKYSCRAPERS

Two aerial photographs of Park Avenue in 1923 and 1932 make immediately clear the new architectural scale and aesthetic of New York at the end of the Twenties, in contrast with the early 20th-century City Beautiful order of the Warren & Wetmore’s Terminal City designs. In the foreground of the bottom image, the Waldorf Astoria hotel looms more than twice the height of the prim palazzi that channel Park Avenue in walls of stone and brick. The Waldorf rises like a mountain above its full-block site that stretches from Park to Lexington Avenue and steps back to a slab crowned by two small ornamental towers that give the skyscraper its Art Deco silhouette. The other slender towers in this atmospheric view looking south to Grand Central are, like the Waldorf, brand new to the skyline.

The new style of setback skyscrapers of the late 1920s boom expressed New York’s exuberant energy in construction and real estate speculation. The shapes of the towers also followed the new rules of the 1916 zoning law that required regular setbacks in the building’s massing, but permitted a tower to rise to unlimited height over a quarter of the area of the site. The RKO/ General Electric Building in the left foreground and the distinctive profile of the Chrysler Building in the center background are examples of this characteristic formula. Even the firm of Warren & Wetmore developed a tower form for their New York Central Building, which, when completed in 1930 as the Railroad’s new office headquarters, had pride of place as the culmination of the southern view to the terminal: the horizontal transformed into verticals in the late 1920s.

The 1923 aerial does prefigure this change. At the far right, the Shelton Hotel is receiving its finishing touches. Completed in 1924, it was one of the first skyscrapers to be constructed in the post-WWI years and thus was also an early example of the impact of the new zoning formula. Architects and critics of the period recognized it as a harbinger of “the new architecture,” praising it for the powerful simplicity of its massing.

View of Park Avenue looking toward the Helmsley Building, Angelo Rizzuto, 1959. Library of Congress.

THE POST-WAR YEARS

The next era of Park Avenue’s development began in the late 1940s. Construction had stalled during the Great Depression and stopped during World War II. The first of the postwar office buildings, 445 Park Avenue, was completed in 1947. By 1957, though, when journalist Jane Jacobs wrote about “New York’s Office Boom” for Architectural Forum, she counted 116 new buildings across Manhattan. The dynamic of growth she outlined was extraordinary:

“What is happening in New York is less an expansion than an explosion of office space. The 40 million sq. ft. added or about to be added represents more than a 40% increase of the city’s office space at the war’s end. The increase alone represents more office space than the total in any other US city. Or, put another way, it equals all the new office buildings in all the rest of the country put together and then half as much again.”

In the 1957 New York Times Magazine article titled “Park Avenue School of Architecture,” architectural critic Ada Louise Huxtable likewise noted: “Of the more than a hundred office buildings constructed or remodeled in Manhattan since the war, Park Avenue’s share of fifteen commercial structures, thirteen of them impressively concentrated in a twelve-block area between 47th and 59th Street, includes the most important examples of the new style.”

The pace of development Huxtable and Jacobs identified can be seen in this 1959 photograph looking south from 52nd Street. At the center of the image 300 Park Avenue illustrates the aesthetic of horizontally-banded windows and solid spandrels that typified the first phase of glass curtain-wall construction. In the foreground, the adjacent cleared blocks from 50th to 52nd Street would soon be filled with nearly identical buildings – identical not just because they were both designed by Emery Roth & Sons, but because their massing was shaped by the setback formula of the 1916 zoning law. At 35 and 30 stories, they were timid investments compared to the 52 floors of SOM’s Union Carbide Building, on the rise in the distance. Yet they replaced the brick-clad Warren & Wetmore apartment buildings that were half their height. Almost all the residential blocks of the first phase of the railroad’s Terminal City would be gone by the 1970s.

(top left) Lever House, Ezra Stoller | ESTO, 1952. Courtesy of SOM

(top right) Seagram Building, Ezra Stoller | ESTO, 1958. Courtesy of Severud Associates.

(bottom) Pan Am (need a citation)

CORPORATE CORRIDOR

“The chief sponsors of the new office buildings were (and are) conservative commercial corporations whose names read like a preferred listing of ‘Who’s Who in American Industry.’ The staples of our civilization – soap, whisky and chemicals – have identified themselves with advanced architectural design and their monuments march up the avenue in a proud parade." This comment by New York Times critic Ada Louise Huxtable referred, of course, to the iconic corporate headquarters of Lever House, Seagram, and Union Carbide – the branding statements of their multi-national companies that set the standard for Modernists for a generation.

Completed in 1952, Lever House, on the far left, was the city’s first true “curtain wall” skyscraper – a simple rectangular slab clad in a taut skin of greenish glass. Lead design partner of the New York office of SOM, Gordon Bunshaft, alternated vision glass with horizontal bands of a darker green that disguised the floor slabs and complied with current fire codes. The overall effect was a gleaming surface that mirrored the surrounding buildings while also revealing the structure within. Lifted up from the street on piloti columns, the tower – which rose above only a quarter of its elevated base – expressed lightness, especially in contrast to its masonry neighbors. As the corporate headquarters for one of the country’s largest detergent and soap manufacturers, the squeaky-clean glass box was a fitting brand advertisement for their products.

Likewise, the Seagram Building, completed in 1958, was designed to project an image of its owner company, the liquor distiller and marketer Joseph E. Seagram & Sons. The selection of the architect — the German-born, but Chicago-based Mies van der Rohe — was a declaration of high-brow taste that carried the endorsement of the Museum of Modern Art and its curator of architecture Philip Johnson, who also collaborated with Mies on elements of the design. The shape of the building was a straight-up tower set back ninety feet from the street on a travertine podium, flanked by reflecting pools. The color of the facade was a deep brown, both in the bronze-tinted windows and the famous mullions in the form of an I-beam that ran the full vertical height in front of the glass to cast shadows that darkened and enriched the surface.

Both Lever House and Seagram exhibited Modernism’s penchant for presenting the building as a simple form, free-standing and surrounded by open space. Unlike all the previous structures of Terminal City, these towers did not rise up from the edge of their lot, but were set back in a plaza or turned perpendicular to Park Ave., breaking the continuity of the street wall that for more than three decades had defined Park Avenue.

21ST-CENTURY PARK AVENUE

By the early 2000s, the modernist office buildings of postwar Park Avenue were aging. At forty to sixty years old, their first-generation glass curtain walls, mechanical systems, and infrastructure for new technologies required refurbishment and new investment. Some, like Lever House, which was already protected as an official New York City landmark, received an expensive new glass skin. Others were simply reclad in more energy-efficient materials or were refashioned with a new look.

The past pattern of demolishing a shorter building and replacing it with a larger and taller one, though, was no longer possible. The revision of the 1916 zoning law in 1961 had dramatically reduced the overall size of new buildings by setting a maximum floor area ratio (FAR) allowed on each lot. Some properties slipped in value, as owners hesitated to make major investments. By 2010, with most of the postwar boom buildings 50+ years old, Park Avenue was beginning to lose its caché. Further, some tenants were leaving for new buildings in other districts, such as the reborn Times Square and Battery Park City. The future rebuilding at the World Trade Center and Hudson Yards threatened further competition.

This was a problem for Park Avenue property owners, but it was also a concern for the city government, which began to consider ways to encourage new construction. In 2017, after much contentious discussion and politicking, the City Planning Commission established a special zoning district called “East Midtown” that allowed the developers of new towers to increase building density by purchasing and transferring additional FAR from designated landmarks or by constructing other public space improvements.

One exception to the long winter of no development was 425 Park Avenue. From as early as 2011, the developer L&L Holding Company, who owned a 1957 Kahn & Jacobs office building with full-block frontage between 55th and 56th Street on the east side of Park, considered a full tear-down and replacement with a trophy tower. After a competition among international “starchitects,” the winner was Norman Foster. In an ingenious design that played within the zoning rules before the passage of the East Midtown rezoning, the architect retained 25 percent of the old building’s structure, but reconfigured its FAR into a 41-story, 860 foot tower. The project was the first of three Foster + Partners projects on Park Avenue.

This virtual exhibition is under construction.