The Museum's March 2015 through March 2016 exhibition TEN TOPS was documented in an online version that was hard-coded and buggy. All the content of that site is transferred here on a new platform, but without changing tenses from present to past.

Distinctive tops that add extra height to high-rises have been characteristic of New York skyscrapers from the first tall office buildings in the 1870s. The word skyscraper, after all, evokes both aerial height and a slender silhouette. The romance of Manhattan's towers has been the inspiration and touchstone for a worldwide surge of signature tops. Stretched spires are also a strategy in the competition for the title of world's tallest building.

Top Ten lists hold a perennial fascination, and debating definitions of height has spawned three official line-ups based on different metrics: 1) the architectural top; 2) the highest occupied floor; and 3) the tip (including added antennas, flagpoles, etc.). But measuring only vertical height succumbs to one-dimensional thinking that ignores important features of skyscraper design and history.

TEN TOPS eschews rankings and focuses on one simple group of the world's tallest buildings: 100 stories and higher. The category begins with the 1931 Empire State Building and now includes nearly two dozen towers worldwide that are completed or under construction. Highlighting ten towers in their categorical context, TEN TOPS peers into their uppermost floors and analyzes the architectural features they share, including observation decks, luxury hotels and restaurants, distinctive crowns and night illumination, as well as the engineering and construction challenges of erecting such complex and astonishing structures.

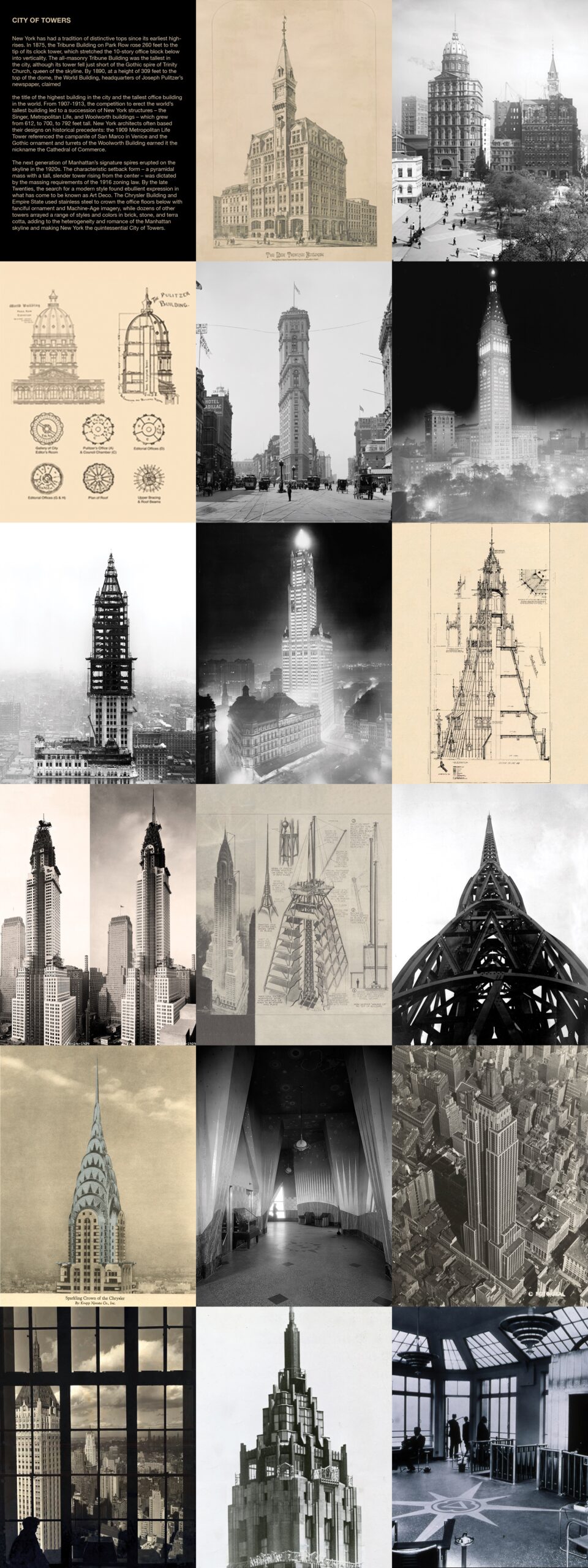

CITY OF TOWERS

New York has had a tradition of distinctive tops since its earliest high-rises. In 1875, the Tribune Building on Park Row rose 260 feet to the tip of its clock tower, which stretched the 10-story office block below into verticality. The all-masonry Tribune Building was the tallest in the city, although its tower fell just short of the Gothic spire of Trinity Church, queen of the skyline.

By 1890, at a height of 309 feet to the top of the dome, the World Building, headquarters of Joseph Pulitzer’s newspaper, claimed the title of the highest building in the city and the tallest office building in the world. From 1907-1913, the competition to erect the world’s tallest building led to a succession of New York structures – the Singer, Metropolitan Life, and Woolworth buildings – which grew from 612, to 700, to 792 feet tall. New York architects often based their designs on historical precedents: the 1909 Metropolitan Life Tower referenced the campanile of San Marco in Venice and the Gothic ornament and turrets of the Woolworth Building earned it the nickname the Cathedral of Commerce.

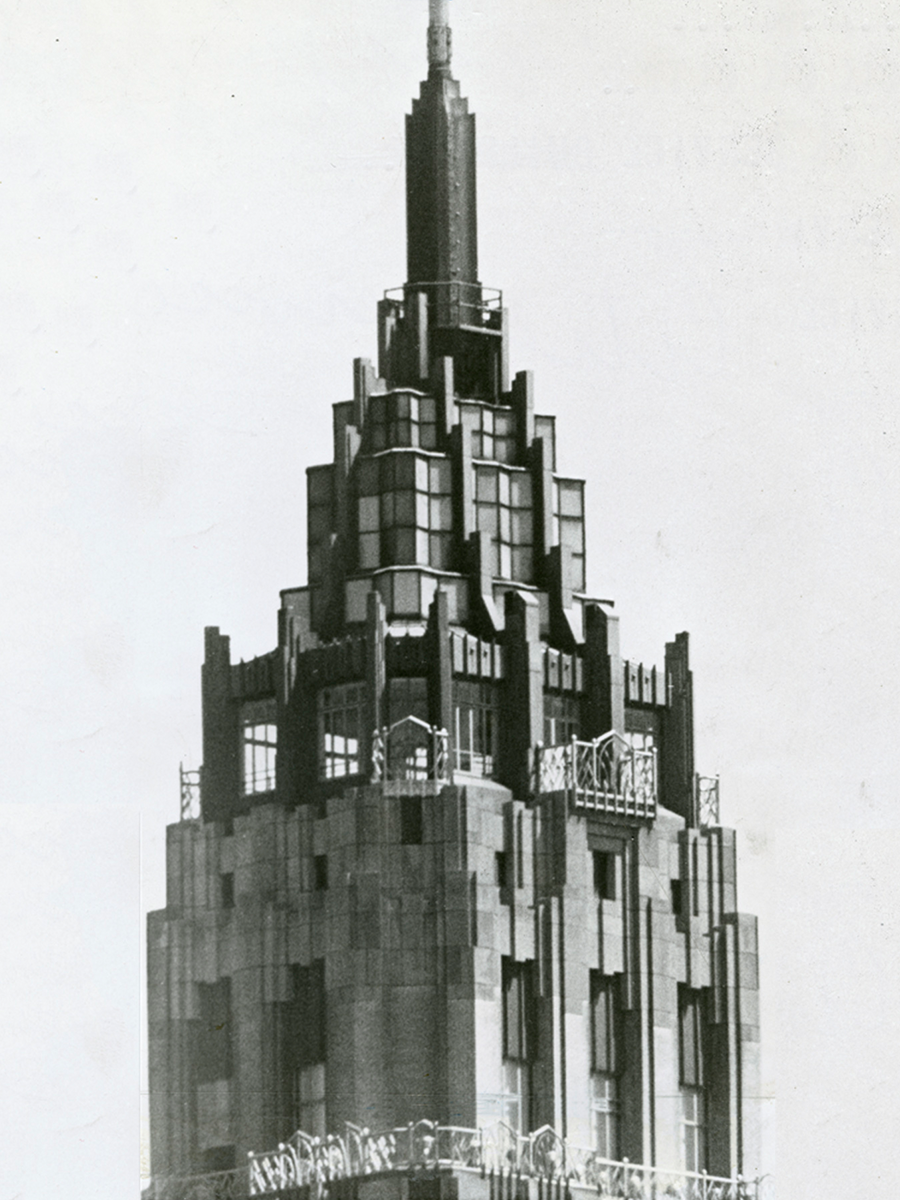

The next generation of Manhattan’s signature spires erupted on the skyline in the 1920s. The characteristic setback form – a pyramidal mass with a tall, slender tower rising from the center – was dictated by the massing requirements of the 1916 zoning law. By the late Twenties, the search for a modern style found ebullient expression in what has come to be known as Art Deco. The Chrysler Building and Empire State used stainless steel to crown the office floors below with fanciful ornament and Machine-Age imagery, while dozens of other towers arrayed a range of styles and colors in brick, stone, and terra cotta, adding to the heterogeneity and romance of the Manhattan skyline and making New York the quintessential City of Towers.

THE TRIBUNE BUILDING

Completed in 1875, the Tribune Building, home of the venerable New-York Tribune, was one of three contemporary tall office buildings - the others were the Equitable and Western Union buildings, nearby on Broadway - that historians have called "proto-skyscrapers." In the early 1870s, these three were also the first office buildings in the city to use elevators, even though passenger lifts had been introduced into hotels and dry goods stores in the late 1850s. The Tribune's two elevators were powered by steam and illuminated by gaslight chandeliers.

At eleven stories, the Tribune was the first tall building on Newspaper Row across from City Hall. It soared above its neighbor and competitor, The Sun, and became the tallest office building in the city by virtue of its clock tower, which reached 260 feet.

The extravagant architectural statement was the project of Whitelaw Reid, who had become editor-in-chief in 1872. Established by Horace Greeley in 1841, the New-York Tribune was the country's most respected and influential political paper and had the largest circulation in the nation for its weekly edition. Reid aspired to erect a "printing palace" that would be the most technologically advanced newspaper operation of the time and would be entirely fireproof, a key consideration after the major fires in Chicago and Boston. The Tribune occupied the eighth and ninth floors: the remaining floors were rented to tenants.

Reid worked closely with the prominent architect Richard Morris Hunt and acted as contractor. Typical of the 1870s, the structure was load-bearing masonry. As the Scientific American wrote on May 1, 1875:

The structure is of great height and immense solidity, and is built of brick laid in cement, with dressings of stone and granite. The finial on the clock tower is 260 feet above the sidewalk, surmounting a building containing sub-cellar, basement, nine stories, and attic. The walls of the lower portion, sustaining the great weight of the masonry, are 5 feet, 2 inches to 6 feet thick. The building is claimed to be absolutely fireproof. No wood is used in its construction, except for floorings, doors, and windows.

THE WORLD BUILDING

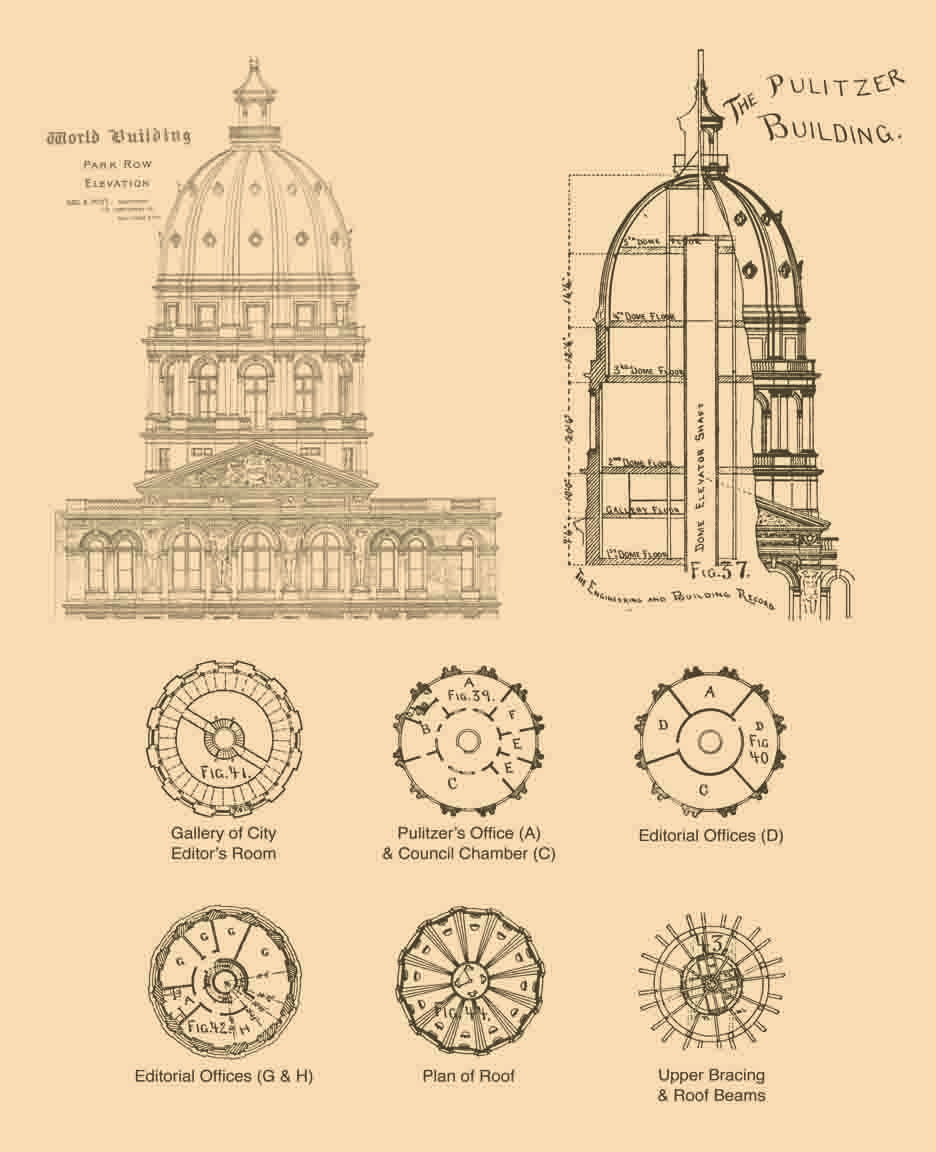

Completed in December 1890 as the newspaper's headquarters, the World Building - officially called the Pulitzer Building expressed the ambitions and business genius of its publisher Joseph Pulitzer. At a height of 309 feet to the top of the dome, the paper's new home on Park Row became the highest building in the city and the tallest office building in the world. (The Eiffel Tower still held the title as world's tallest structure). Designed by architect George B. Post, the building comprised 18 stories - with 12 floors of rentable office space and four levels for the newspaper's editorial offices in the drum and dome.

No expense was spared on the elaborate façade of red sandstone and terra cotta, Renaissance ornament, and figurative sculpture, which gave the appearance of an Old World masonry structure, while hiding the advanced metal-cage construction that Post encased within the walls.

The distinctive dome provided a visual identity for the newspaper. The image of the gilded top was used in advertising, graced covers of The World Almanac, and created a landmark on the skyline. At night, the top was illuminated with electric lights and the lantern at the top of the observation platform acted as a beacon for ships at sea.

In a booklet printed for the tower's debut, the paper effused:

From Jersey's shores, from Brooklyn Heights, from the beach of Staten Island, from points far remote, it is first discerned as one approaches New York looming above the busy metropolis, above Trinity's lofty spire, above the tall towers and high roofs of its neighbors-a giant among the giants.

World Dome

The gilded dome of the World Building was a symbol both of Pulitzer's success and a workplace for his staff. Daily editorial meetings took place in offices in the lantern and dome; the five levels housed editors, reporters, telegraphers, and copyreaders, in total about a hundred. On the second level was Pulitzer's private office, a council chamber, and the offices of other editors. Other departments occupied the sunlit upper floors of the main block, with reporters writing stories and linotype operators and compositors preparing galleys and headlines on floors 10 through 12. The roof top level provided space for the graphic artists, the photographers' room, the photoengraving department, proof press, managing editor's room, and the Sunday room.

Access to the public observatory at the top of the dome was reachable by a cylindrical elevator cab direct from the lobby. There, visitors could enjoy the unparalleled views afforded by the building's superlative height. For an admission fee of five cents, tourists rode an express elevator that shot from the lobby to the upper floors, where they could access the cupola of the dome by a staircase. An article in The World from 1897 captured one visitor's encounter with the elevated view:

The long drawn-out mighty city was dipped in sunshine, a dark blue sky was above me, and in a picturesque manner the white buildings appeared to be embossed upon the scene--so different from the red brick. It was not only roofs that one was looking at; one could see the entire buildings in their grandeur, as they border upon wide streets--and then again the difference in lights; here a three-story, there a five, another a twelve, and even eighteen and twenty-story houses.

TIMES TOWER

Few people today realize that the building at the heart of Times Square covered with LED signs and animated screens - the tower from which the nationally televised New Year's Eve ball drops - is the same structure that from 1905 to 1913 served as the headquarters and printing plant of The New York Times newspaper. Built at the direction of the legendary owner and publisher Adolph Ochs, who had purchased the ailing Times in 1896, the new building was part of his larger plan to reinvigorate the newspaper. Ochs intended a building to "wake up the nation" and to call attention to the paper's resurgence under his leadership.

Ochs decided to relocate the Times from its 1889 high-rise on Newspaper Row to the a site more than four miles north - a small, but highly visible triangle of land bounded by Broadway, Seventh Avenue, and 42nd Street in a burgeoning area of hotels and theaters then known as Longacre Square. He hired the architect Cyrus Eidlitz and his partner Andrew McKenzie to design a 25-story skyscraper modeled on Giotto's campanile, the medieval bell tower of the Florence Cathedral, which the publisher had admired during his European travels. From a slender base that rose fifteen stories, an even narrower tower at the south end added ten floors, including an octagonal rooftop observatory for Ochs. Above the twelfth floor, the facade was encrusted with terra-cotta ornament that multiplied toward the top in ogee arches and projecting cornices.

The Times Tower was constructed in 1904, the same year that the IRT subway opened. The stop at 42nd Street was given the name Times Square. The below grade levels of the tower contained the printing presses and other machinery of production and could connect directly to the platforms of the IRT subway for speedy distribution north and south on that route. The historicism of the architecture was thus balanced by the modernity of the concept of paper publication and distribution.

METROPOLITAN LIFE TOWER

In the late 1880s, the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company sold its building in Lower Manhattan and moved uptown to Madison Square and 23rd Street, where it erected an 11-story headquarters, completed in 1893. Rapid growth required more and more space for burgeoning staff and files, until annexes covered nearly the entire block. After acquiring the last remaining parcel and demolishing the Madison Square Presbyterian Church, the company planned its signature campanile as a symbol of its success.

In 1909, the Metropolitan Life Insurance Tower claimed the title of world's tallest office building from the 612-foot Singer Building by climbing to 700 feet. Designed by architect Napoleon LeBrun and Sons, the 50-story structure took the form of a slender shaft modeled on the Renaissance bell tower of San Marco in Venice. The sharply pitched roof is topped with a cupola and lantern that would flash as a signal to ships at sea.

A lighted 26-foot-diameter clock adorned each side of the tower. Four chimes, which were said to be heard up to thirty miles away, rang four times on the quarter, eight on the half, twelve on the three-quarter, and sixteen on the hour. A flash of light accompanied each ring from the top of the tower, which was visible within 100 miles. The tower's timekeeping had the capability to reach five million people.

In the 1960s, the expensive Tuckahoe marble façade was subjected to an aggressive remodeling campaign in which most of the classical detail was removed, as well as the balconies and prominent cornice. The marble façade was replaced with sheer limestone panels, so the tower would match the modernized base. Today, the clock faces remain the only memory of the ornate façade.

WOOLWORTH BUILDING

Frank W. Woolworth, the five-and-dime store king, did not start out to build the world's tallest office building. The earliest drawings for the project in early 1910 depicted only twenty stories. But over the course of the year, with the encouragement and inspiration of architect Cass Gilbert, the client's ambitions grew, and their shared desire to erect a record-breaking tower became clear.

On December 20, 1910, Woolworth sent surveyors to determine the precise height of the tip of the Metropolitan Life Tower - then the world's tallest building - which he clearly intended to surpass. On January 20, 1911, The New York Times published an interview with Woolworth in which he boasted of his intentions to erect a 750-foot tower. By April, the final height of 792 feet was established and the project was promoted as the "world's greatest skyscraper."

While the height of the Woolworth Building can be precisely measured, the number of floors in the tower was open to interpretation and was variously reported by the owner and in newspapers as either 55 or 60 stories. At the opening ceremonies, Woolworth claimed the higher number. His new count apparently included short mezzanine stories within the tower - one within the pyramidal roof seen here as an unclad steel skeleton - and another in the lantern in the tower's pinnacle. A hand-written note of 1920 in the Cass Gilbert archives of the New-York Historical Society explained: "The owners of the building have numbered the pipe galleries, and they now call the building 60 stories high."

Exaggerating floor counts in skyscrapers has become a common practice, since higher numbers seem to carry additional prestige. Today, especially in the lavish new condominium towers in New York, inflating the floor count is widespread. For example, the 75 constructed floors of the billionaire roost One 57 is marketed by the developer as "90 stories of elevated living."

Opening Night

Eighty thousand incandescent bulbs illuminated the New York night on April 24, 1913, when the Woolworth Building opened with a ceremony as fantastic as the structure itself. President Woodrow Wilson pressed a button in the White House that simultaneously lit every interior floor and the brilliant tower beacon. In the lantern at the tower's tip, engineers designed a cluster of twenty 1,000-watt lamps to creating "an immense ball of fire." Scientific American described it as "a great crystal of flaming light" that caused "the other lighting spectacles of the metropolis to fade away before it."

Witnessed by multitudes and wired to press around the world, the opening celebration was a career-crowning achievement for the tower's owner, Frank W. Woolworth, who paid for the skyscraper with his personal fortune and took a hands-on role in every decision of its design and promotion. Dubbed the "Cathedral of Commerce" for its neo-gothic ornament and soaring silhouette, the lofty tower was both a marvel of early 20th-century technology and a masterpiece of the architectural arts. Years earlier, the architect Cass Gilbert had defined the skyscraper as "a machine to make the land pay." But with the Woolworth Building, he found an ideal client willing to elevate the tower beyond the realm of real estate to the status of a civic monument.

As a savvy marketer Woolworth justified the extra expense as effective advertising, noting that both the iconic presence of his tower on the New York skyline and its superlative height had immeasurable value. Indeed, today the Woolworth Building remains the city's most beloved and inspiring landmarks.

Woolworth Spire

The Woolworth Building project specifications called for handcrafted and costly "foliate or intricate ornamental parts." The Façade was clad in glazed terra-cotta, molded into gothic crockets, pinnacles, and gargoyles. The roof was covered in copper sheets and ribs that patinated to a soft green color and crowned with lacey copper tracery. An example of which from a lower floor of the building hangs on our gallery's west wall. The delicate drawing from the Cass Glibert office at the left illustrates the extraordinary attention to details that characterized the design, even almost 800 feet above the sidewalk.

Like the World Building and others before it, the Woolworth Building featured a public observation deck that offered tourists the chance to combine "the thrill of extreme height coupled with the sensational geography of distance," as the architectural historian Gail Fenske has written.

By 1916, the pinnacle observatory drew more than 100,000 people a year from over sixty countries. To reach the top, sightseers purchased tickets for 50 cents (around $11 today) at a booth near the Barclay Street entrance, then shuttled in a high-speed elevator to the 54th floor, where they could buy postcards, souvenirs, and ice cream at the "highest retail location in the world." To ascend to the 58th-floor outdoor terrace, they could take a six-person circular glass elevator or climb a spiral stair.

From this aerie, the city lay below in a thrilling panorama. As described in the illustrated souvenir guidebook Above the Clouds and Old New York (1913) by H. Addington Bruce:

Looking down on the thousands of great structures, the wonderful bridges that span the East River, the beautiful parks, the great steamers berthed at piers along the rivers, one realizes the grandeur and vastness of the metropolis. The serried peaks made by the giant buildings, towers, church steeples all seem to contend with each other for the distinction of "highest and greatest." But above them all rises the Woolworth Building, calm and unassailable.

Today, the tower floors pictured here are being transformed into a single seven-story penthouse apartment priced at more than $100-million.

CHRYSLER BUILDING

The most fanciful and famous top of all of Manhattan's ornamental beauties is certainly the Chrysler Building, a quintessential expression of Jazz-Age New York. Its flashy modernism was communicated through the stainless steel crown with its crescendo of seven scalloped domes and spiky triangular windows. The needle spire stretched its height to 1,046 ft., which won it the title of tallest building in the world from 1930 to 1931, until the completion of the Empire State Building.

The project began in 1927, when entrepreneur William H. Reynolds, known for developing Dreamland at Coney Island, hired architect William Van Alen to design a speculative skyscraper, to be called the Reynolds Building, for a site on the northeast corner of Lexington Avenue and 42nd Street. The project was planned to rise 67 stories and 808 feet.

In October 1928, the land lease and plans were acquired by the automobile magnate Walter P. Chrysler, who was in the news as Time Magazine "Man of the Year" for 1928. Chrysler developed the tower as a personal project, not as a company headquarters: no corporate funds were used in its financing or construction. Van Alen altered the scheme to reflect his new client, and the front page of the New York Times reported on October 17, 1928 that Chrysler's 808-foot tower would have 65 floors of offices and, above, a duplex apartment, and a "three-story observation dome constructed of bronze and glass, culminating in a spire."

The steel framework of the tower was completed in September 1929. During that year, the announced height had grown to 905 feet, according to newspaper accounts, although plans had been made in secret for an addition that would reach to 1,046 feet. This altitude would exceed the announced height of its rival 40 Wall Street, which was topping out that same month at 927 feet to the tip of its needle spire.

Chrysler Construction

The progress photographs and construction diagram illustrate the remarkable feat of erecting of the top of Chrysler Building and help to clarify details about the often exaggerated story of a rivalry: a "race to the skies" between two skyscrapers and two architects, William Van Alen and his former partner Craig Severance, with Yasuo Matsui, the architect of 40 Wall Street.

The boom in skyscraper construction in New York from the mid-1920s was at once reality-based in the white-hot investment economy and also a real estate bubble. Dozens of 30- and 40-story buildings were added to the Manhattan skyline both downtown and in midtown. To stand out from this crowd, a few taller towers were announced. The most ambitious were the Chrysler Building and 40 Wall Street, both of which were to surpass the 792-foot height of the Woolworth Building spire, which was still the city's tallest building.

The more lofty title of "world's tallest building" belonged to the 1889 Eiffel Tower in Paris at 300 meters/ 986 feet. This was apparently the marker that Walter Chrysler had in mind when he authorized the attenuated new design for a 77-story building with Van Alen's "vertex," the 7-scalloped domes of the tower's stainless-steel crown.

Both the Chrysler Building and 40 Wall Street topped out in the fall of 1929, and newspapers began to pay attention to the "race." As the progress photos (above), on 10/14/29, only a truncated tip of the needle poked out of the dome. On October 23 - the very day before the stock market crash that signaled the beginning of the Great Depression - a 185-foot steel spike was hoisted from within the vertex dome to claim a vertical height of 1,046 feet. Incredibly, the work took only 90 minutes: it would have made for great film footage or photojournalism - if only the press had been alerted.

In fact, it was only after 40 Wall Street topped out in November that the superior height of the Chrysler Building was promoted to the press. The scaffolding that encased and shrouded the dome so the workers could finish the stainless steel cladding stayed in place until the spring of 1930 when the gleaming spire slowly emerged from its chrysalis.

The Vertex

In the article "The Structure and Metal Work of the Chrysler Building" in the October 1930 issue of Architectural Forum, architect William Van Alen explained the design and construction of the tiered dome and "vertex."

A high spire structure with a needle-like termination was designed to surmount the dome. This is 185 feet high and 8 feet square at its base. It was made up of four corner angles, with light angle strut and diagonal members, all told weighing 27 tons. It was manifestly impossible to assemble this structure and hoist it as a unit from the ground, and equally impossible to hoist it in sections and place them as such in their final positions. Besides, it would be more spectacular, for publicity value, to have this cloud-piercing needle appear unexpectedly.

Therefore, the spire was fabricated and delivered to the building in five sections and assembled inside the dome. The drawings created for Popular Science Monthly in 1930, above, shows a cutaway diagram of the assembled spire, spanning seven floors of an open well within the steel skeleton ready to be hoisted into place.

A scaffolding of steel pipe draped with heavy wire netting was erected around the dome (and eventually the spire) to protect sheet-metal installers working on the building's ornamental terminus. Because of the curving shape of the dome's form, measurements for the sheet steel needed to be verified in the field. The bulk of the work was thus carried out in metalworking shops located on the sixty-seventh and seventy-fifth floors of the building.

Chrysler Spire

Below the 61st floor, the Chrysler Building was a fairly conventional office tower, with a shape that followed the setback formula required by the city's zoning law. Above the last setback and the stainless steel eagle-head gargoyles, though, both the program of the interior spaces and the architectural ornament entered the realm of the eccentric.

On floors 66 to 68, below the public observation deck (the second level of triangular windows), was the Cloud Club, a private dining and lounge space for executives who paid a $300 annual fee for membership to enjoy either the double-height dining room with Art Deco details or a more cozy Tudor lounge and “Old English” bar and grill. Walter Chrysler kept a private dining room with black etched-glass panels that looked north to Central Park. His offices in the tower, though, were outfitted in a baronial style of wood paneling and upholstered furniture.

In its exterior form and ornament, the scalloped dome and finial, which seems like a silver helmet on an almost-anthropomorphic “head,” has no precedent, nor any clear explanation. An unnamed critic wrote in the Architectural Forum in October 1930:

The Chrysler … stands by itself, something apart and alone. It is simply the realization, the fulfillment in metal and masonry, of a one-man dream, a dream of such ambitions and such magnitude as to defy the comprehension and the criticism of ordinary men or by ordinary standards.

The question arises: did the critic mean this singular dream was Chrysler’s or Van Alen’s? Most likely the former, because without an indulgent client, such an extravagant work would never have been realized. But Van Alen’s unfettered imagination seems far richer than Chrysler’s personal taste. The two men’s collaboration, however, ended in acrimony and a lawsuit over payments, and even after the Depression Van Alen had little work.

Chrysler Observatory

The 71st floor of the Chrysler Building was used as an observatory from 1930 to 1945. Visitors bought a ticket in the lobby and ascended by Van Alen’s colorful elevator car, patterned in precious woods, to the observation level. There they could circle the periphery through a corridor and vaults painted with a celestial ceiling of stars and golden rays, reminiscent of German expressionist film sets like the 1926 Metropolis. The architectural writer Eugene Clute described the space in Architectural Forum in October 1930:

The gallery follows the octagonal form of the perimeter of the tower and surrounds an octagonal space in which are grouped the elevators and various utility features. The ceiling is high. At points along the outer wall of the gallery, where heavy members of the structural steel slant inward from floor to ceiling, these members have been encased and the resulting form has been repeated upon the inner side of the gallery. This produces a series of openings which provide effective visits from one section of the gallery to another. Here, enclosed in a glass case, is Walter P. Chrysler’s box of workman’s tools with which he started his career. This gallery provides pleasant surroundings from which visitors may enjoy the remarkable views of New York and adjacent counties that can be had through the wide windows on every side.

The small triangular windows that were the result of the dome’s design, however, created odd angles for viewing the city below. The Empire State Building, completed a year later, with its outdoor spaces and unobstructed vistas, became the more popular elevated experience, and the Chrysler Building’s observatory continued to operate for just fourteen more years.

ROOM AT THE TOP - 40 WALL

The view from skyscraper heights – the elevated board room or corner office – holds much prestige. This photograph of the early 1930s captures the commanding view from the top floor of 63 Wall Street, built in 1929 as the headquarters of the patrician bank Brown Brothers & Co., later Brown Brothers Harriman & Co. The large window looks north past the peaked tower of 40 Wall Street and the Woolworth Building and beyond, to the silhouette of the Empire State Building in midtown.

The top floors of towers in the financial district were often occupied by corporate suites and business clubs where bankers, lawyers, and other professionals lunched, drank, and connected with their kind. The smaller financial district lots limited the floor area of towers, and owners saw little advantage in accommodating mass-tourism in observatories like those at the Woolworth Building or Empire State.

At 40 Wall Street, the 69th and 70th floor “observation rooms” were reported to be able to accommodate a group of one hundred, but in general, the topmost floors were highly exclusive. One of the most spectacular spaces was the 49th floor of One Wall Street, headquarters of the Irving Trust Company, where a two-story vaulted ceiling covered in luminescent pearl shells afforded a swank meeting space for executives.

CITIES SERVICE BUILDING

The Wall Street area’s most spectacular observation gallery crowns the former Cities Service Building at 70 Pine Street. On the 66th floor, a glass-enclosed room only 23 x 33 feet with six outdoor balconies, created a solarium-like space by day and a glowing crystal jewel by night. Originally planned as the private “watch tower” for the penthouse apartment of Cities Service founder, Henry L. Doherty, in 1932 the upper floors instead became corporate offices and an observation gallery opened to the public. It could be visited from 10am to 6pm at a price of fifty cents, and a quarter for Cities Service employees and building tenants.

At its opening, the observation gallery received considerable publicity for its healthful upper-level air and sun. “It does pep you up,” attendant Martha Midboe told the Evening Post. A visiting bond seller told another reporter that he enjoyed the room “above the sordid chitchat of the Street” and the lofty view “where I can watch my ship come in.”

Architectural historian Daniel Abramson described the appeal of visiting the Cities Service Building’s living room-like observation gallery and the benefits of the clear air on its terrace overlooks and the 360-degree view across rivers, harbors, and mountains see from its expansive windows. “At this height, in the eerie skytop quiet, the city loses its human definition, becomes abstracted and itself seemingly naturalized.” The European modernist architect Le Corbusier remarked about a similar nighttime view from another skyscraper vantage, “No one can imagine it who has not seen it. It is a titanic mineral display, a prismatic stratification shot through with an infinite number of lights, from top to bottom, in depth, in a violent silhouette like a fever chart beside a sick bed. A diamond, incalculable diamonds.”

Today, the top three floors of the building are being converted into a restaurant and lounge as part of an apartment and hotel conversion project led by Rose Associates.

Cities Service Observation Gallery

In his book Skyscraper Rivals: The AIG Building and the Architecture of Wall Street, the architectural historian Daniel Abramson described details of the modernist design and the elite and invigorating experience of a visit to the glass-enclosed gallery atop the Cities Service Building:

Visitors ascended into Doherty’s “watch tower” observation gallery either up narrow stairs on the north side or by an adjacent small elevator running from the 60th floor. The metal-clad cab rose through the observation gallery floor—then amazingly descended back beneath hinged hatches. The observation gallery’s deck now lay completely unobstructed in every direction through continuous banks of windows from knee level up, and around the chamfered glass corners. Across the terrazzo floor lay sleek modern tubular steel furniture. Phones plugged into the floor. At the center a compass pointed out the cardinal directions and enclosed the Cities Service emblem. Glass doors at the corners and north and south sides led out onto six small slate terraces, enclosed only by chest-high aluminum railings, that felt like crow’s nests pitched out into the harbor air. Below was the city. South across New York harbor lay Staten Island and the New Jersey coast. West across the Hudson shimmered New Jersey’s inland mountains. To the north appeared glimpses of Westchester County and to the east, Babylon and Huntington on Long Island.

Continuing, he evokes the romance of the views in language that resembles the language of literature of the Twenties:

Architecture dwindles to its starkest essence: a cloud-capped primitive hut. The corners dissolve, walls are reduced to thin piers, the roof to nearly nothing. From the terraces one can hardly see the supporting skyscraper below. In the small space, with the elevator sunk in the floor, one can imagine being all alone, as Doherty must have dreamed, magically levitated, master in vision of the metropolis’ great sweep, standing at the center of the marble compass on the pivot of the universe. The bracing bodily experience intensifies physical self-awareness, as if one has ascended a man-made mountain in transcendence of the reality below.

EMPIRE STATE BUILDING

Completed in 1931, The Empire State Building ruled as the world’s tallest building for forty years, until the completion of the North Tower of the World Trade Center in 1971. Its height, however, had not been set at the start of the design process in September 1929. Rather, it evolved from early schemes for a flat-topped structure – first of 80 stories, then 85 floors with a roof top observation deck – then to the equivalent of 102 stories with the addition of the 200-foot mooring mast.

In December 1929, newspapers reported that future world’s tallest building would be topped with a signature feature, a stainless-steel spire that was justified as functional by serving as a landing station for dirigibles for long-distance business travelers. The Chrysler Building had topped out in October 1929 at 1,046 feet, surpassing 40 Wall Street at 927 feet. The Empire State’s mooring mast - which brought the total height to 1,250 feet – was clearly intended to decisively claim the title of world’s tallest building.

The Empire State was not just taller than other skyscrapers, it was bigger by every measure. Its skeleton frame required 57,000 tons of steel, compared to 21,000 tons for the Chrysler Building. Its net rentable area was 2.1 million sq.ft. (as calculated in 1931), as opposed 850,000 for the Chrysler Building and 845,000 for 40 Wall Street. In other words, the combined floor areas of the next two tallest buildings on the world did not equal that of the Empire State alone.