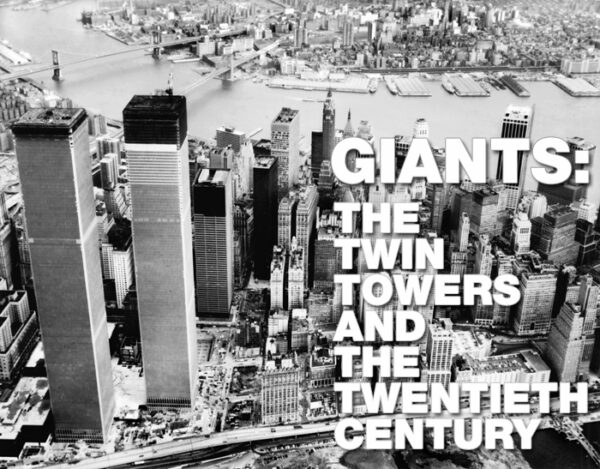

GIANTS: The Twin Towers and the Twentieth Century

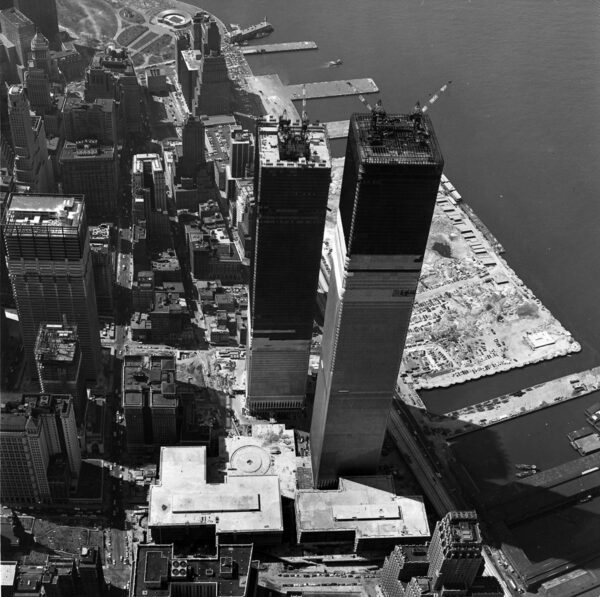

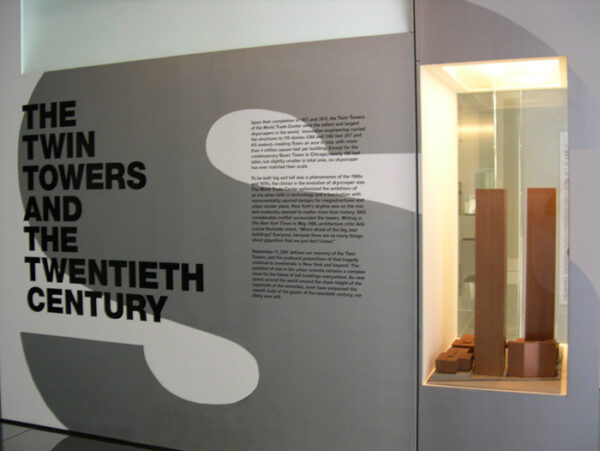

Upon their completion in 1971 and 1973, the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center were the tallest and largest skyscrapers in the world. Innovative engineering carried the structures to 110 stories – 1368 and 1362 feet (417 and 415 meters) – creating floors an acre in size, with more than 4 million square feet per building. Except for the contemporary Sears Tower in Chicago, nearly 100 feet taller, but slightly smaller in total area, no skyscraper has ever matched their scale.

To be both big and tall was a phenomenon of the 1960s and 1970s, the climax in the evolution of skyscraper size. The World Trade Center epitomized the ambitions of an era when faith in technology and a fascination with monumentality spurred designs for megastructures and urban master plans. New York’s skyline was on the rise, and modernity seemed to matter more than history.

Still, considerable conflict surrounded the towers. Writing in The New York Times in May 1966, architecture critic Ada Louise Huxtable noted, "Who’s afraid of the big, bad buildings? Everyone, because there are so many things about gigantism that we just don’t know."

September 11, 2001, defines our memory of the Twin Towers, and the profound proportions of that tragedy continue to reverberate in New York and beyond. The question of size in the urban scheme remains a complex issue for the future of tall buildings everywhere. As new spires around the world exceed the sheer height of the supertalls of the seventies, none have surpassed the overall scale of the giants of the twentieth century, nor likely ever will.

The original 2006 virtual exhibit, which recorded the installation in the same images and text here, was created in Macromedia Flash, a platform that is no longer widely supported. The legacy page has been restored following HTML5 standards.

Installation Views

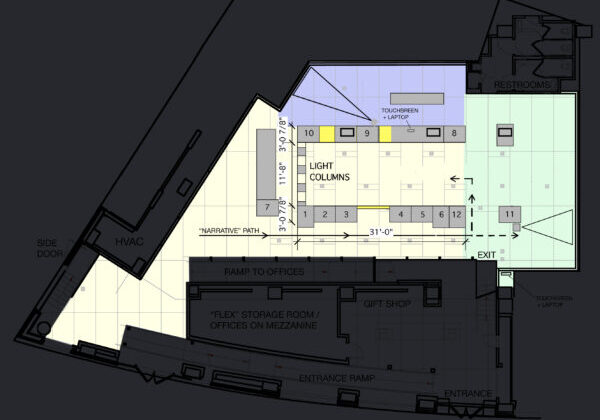

The installation design for GIANTS, which ran from September 8, 2006 — April 15, 2007 was created by Local Projects.

Read a description of their proposal.

GIANTS: The Twin Towers and the Twentieth Century will be a mixed-media exhibition that investigates and celebrates the World Trade Center Twin Towers as skyscraper history. It will use a unique mixture of media, graphics, and exhibit design to evoke the incredible size, ambition, and impact of the towers, placing them in historical context as the culminating architectural event of the twentieth century.

The centerpiece will be a floor to ceiling light sculpture that will evoke the reeling heights of the towers. The sculpture will be a series of parallel vertical lights, floor to ceiling, that visitors will be able to approach and walkthrough. The startling size and verticality of the towers will be brought forth by placing these lines of light in the museum’s space, with its endless mirror effect of the floor and ceiling. The space will be completely transformed to evoke the remarkable stature of towers and to set the stage for their story. This reverential space will bring forth the mass of the towers with an abstraction of their design.

Planning

Problems and Plans

The World Trade Center was one piece of a master plan to revive the declining fortunes of lower Manhattan. Two key problems in the 1950s and 1960s were the obsolescence of the working waterfront and aging office stock in the financial district. The historic finger piers were outmoded, first by larger ships with deeper drafts and then by containerization which drove shipping to relocate to the vast, vacant expanses of the New Jersey lowlands. In addition, a corporate exodus to more modern towers in midtown threatened the status and survival of Wall Street as a business district.

A World Trade Center

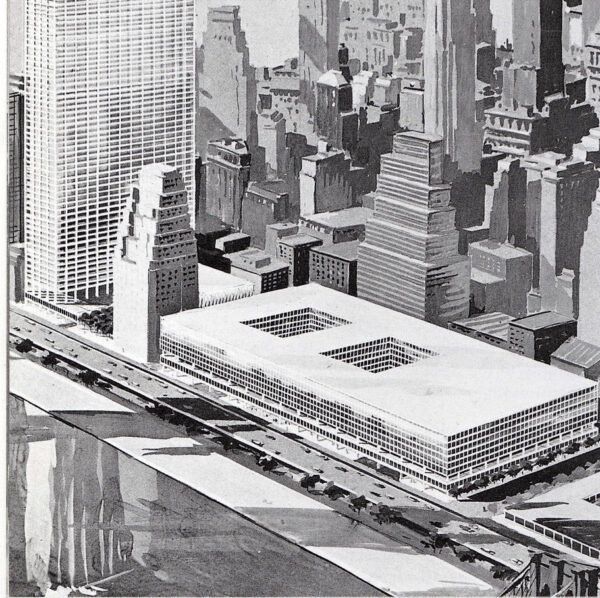

The idea for a World Trade Center was promoted in the late 1950s by the Downtown-Lower Manhattan Association (DLMA), a powerful organization of business interests led by David Rockefeller of Chase Manhattan Bank. A new complex of buildings was planned for a site on the East River that would centralize the shipping and merchandising of imports and exports, bolstering maritime activities and the city’s economy. The architectural firm of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill prepared a scheme and set of renderings.

With the endorsement of City Hall, the DLMA enlisted The Port of New York Authority (now the PANYNJ) as the best potential developer for a "World Trade and Financial Center." In March 1961, the Port Authority issued a report favoring the plan, and the City reluctantly agreed to cede both control over the land and the annual property-tax revenues.

Later that year, plans for the Trade Center shifted to the west side Hudson River waterfront to accommodate New Jersey interests and to connect to the commuter line of the Hudson and Manhattan Railroad. In the spring of 1962, the two states approved the new location, and the Trade Center legislation was joined with the Port Authority's purchase and modernization of the rail line, now PATH.

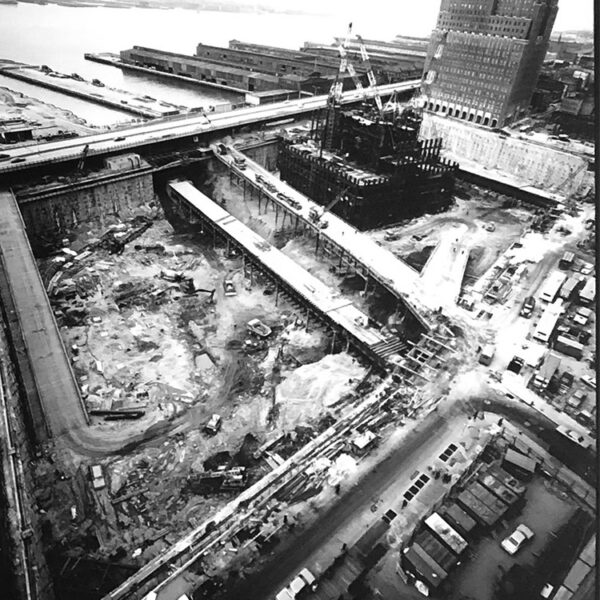

THE SUPERBLOCK

“Superblock” is the planning term of the 1960s that describes the radical redesign of the traditional street pattern. Fourteen city blocks were combined into a single parcel and streets were de-mapped to create a zone free of vehicles. Surrounding streets were widened threefold, and the almost-square site was extended on the north to include two blocks for an electrical substation.

Seven buildings occupied the sixteen-acre site of the World Trade Center complex. The pair of 110-story 1 WTC and 2 WTC, the North and South towers, and the “five-acre plaza’” were the centerpiece of the design. Creating the edges of the site were low-rise structures, a suite of seven story buildings known as 4 WTC, 5 WTC, and 6 WTC (the U. S. Customhouse), all designed by architect Minoru Yamasaki to harmonize with the towers and to frame the plaza.

The building with the address 3 WTC, the Marriott Vista Hotel on the southwest corner of the plaza on West Street, was envisioned in the original site plan, but was designed by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill and completed in 1981. The forty-seven story 7 WTC (also destroyed in 9/11) was completed in 1987.

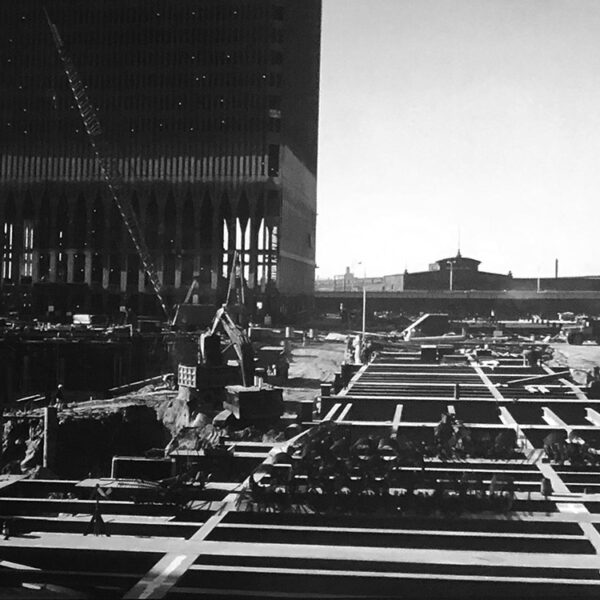

Excavation

As preparation for construction began, World Trade Center site excavation posed significant challenges. The foundation itself was to be six times as large as that of the usual 50-story skyscraper, and geography, geology, and the logistics of urban infrastructure were all factors to be considered.

Half of the site consisted of landfill. This situation, when coupled with the site’s proximity to the Hudson River, meant that a system had to be devised to prevent water from seeping into the foundation. The solution was found in a method known as slurry-wall construction, used on this project for the first time in the United States. In effect, a four-sided dam was created around the troublesome parts of the site, employing 152 walls, each of them 22 feet long, 3 feet wide, and 70 feet deep.

The 16-acre site, known as the “bathtub,” also had a PATH (New Jersey Transit) subway tube running through it. By bracing the tube with a series of supports, it was ensured that at no point during construction was service interrupted. The number 1 line of the New York City subway also ran along the eastern edge of the site. Phone lines had to be removed as well, and again a technique was devised so as not to disrupt service.

Architecture

In 1962, after a series of design studies developed with a team of prominent New York architects, the Port Authority awarded the commission for the World Trade Center to Minoru Yamasaki of Troy, Michigan. It was a surprising choice, since the tallest structure Yamasaki had designed previously was a 22-story high-rise in Seattle. To ensure efficient floor plans and to produce the thousands of construction drawings required, the Port Authority hired as associated architects New York’s most prolific skyscraper firm, Emery Roth and Sons.

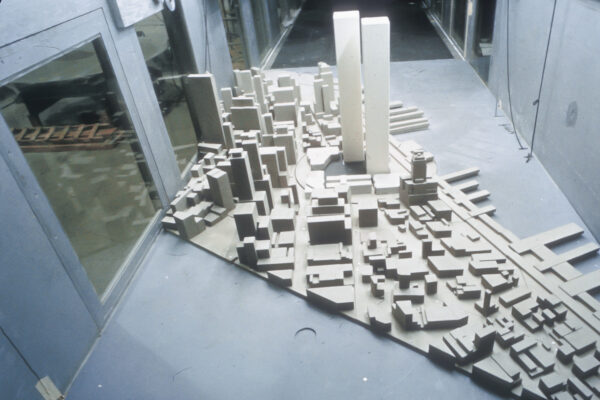

The Port Authority’s program was simple: 10 million square feet of office space built over a mass transit station. There was no prescribed number, height, or configuration of the buildings. Yamasaki and his associates built a context model of the site and began to experiment with different massing studies. Although they ultimately tested over a hundred schemes, on the seventeenth variation Yamasaki fixed on the idea of two square-footprint towers of about 80 stories, set askew in a five-acre plaza framed by low-rise buildings. The Port Authority later increased the height to 100 stories, then to 110 in order to make the towers definitively the world’s tallest. Another key architectural decision was to employ an exterior load-bearing wall with narrow “pinstripe” columns–sheer verticals, soaring straight from the plaza into the sky.

Engineering: Supertall

Realizing the design for unprecedented height and scale of the Twin Towers depended on the structural engineer. In April 1962, at the same time that Yamasaki signed a contract with the Port Authority, the Seattle based firm of Worthington, Skilling, Helle, Christiansen, and Jackson won their commission, and the young soon-to-be partner Leslie E. Robertson became the lead engineer on the project.

Supertall towers, a term that describes buildings of more than 80 stories, posed new engineering problems. The world’s tallest building from 1931 until the completion of the World Trade Center in 1972 was the Empire State Building, an 85-story office tower of 1050 feet, topped by a slender metal mooring mast rising to 1250 feet.

The height of the Twin Towers was described as 110 stories, measured from the plaza. From the perspective of design and construction, though, the towers rose more than 1,450 feet above their foundations in bedrock. The North Tower measured 1368 feet and the South Tower 1362 feet to their flat rooftops, surpassing the tip of the Empire State's spire by more than 100 feet and its top floor by more than 300 feet. Each building had 111 floors, with 116 framed levels including below-grade services. On the North Tower, the TV mast raised the height to 1,815 feet. With 59 closely spaced columns per side, the towers were 209 feet square, and each floor was nearly an acre.

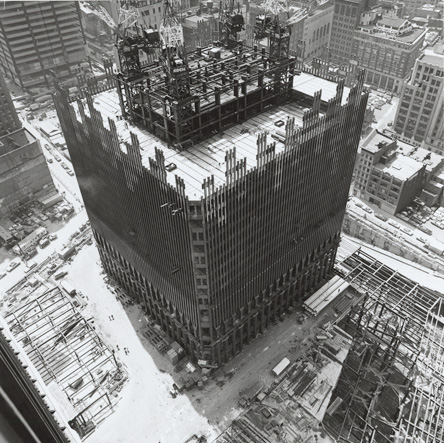

Tube Construction

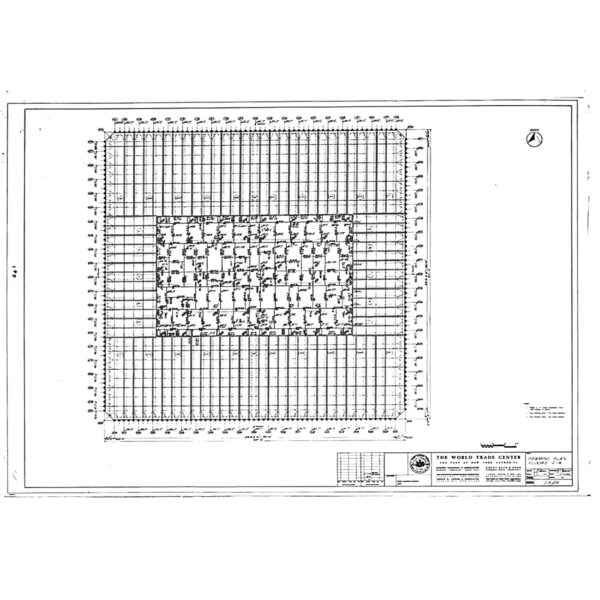

The Towers were among the first of a new type of skyscraper to use “tube” construction in which the outside walls of structural steel acted as a thin shell carrying the building’s weight. The tube cantilevered from its foundations to supply all of the resistance to wind and earthquake forces and to stabilize the core against lateral buckling. The system eliminated the need for a conventional rigid skeleton frame and allowed a reduced story height of 12 feet and floors with a column-free, clear span of up to 60 feet.

Prefabrication

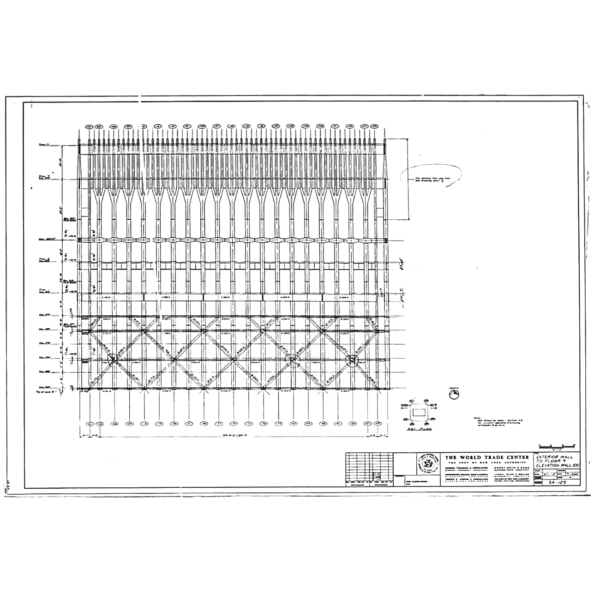

The prefabrication of structural components was developed to a point unprecedented in high-rise buildings, and the detailed design for most of the steelwork was presented to manufacturers for the first time in digital format on IBM punch cards. Nearly 6,000 prefabricated wall panels, three stories high and three columns wide, 36 x 10 feet, were stacked and welded to create the steel bearing wall. The floor construction was composed of 5,716 prefabricated floor panels, generally 20 x 60 feet, including steel deck and electrical raceways.

Damping, Shaftwall, Rooftop Space Frame

Other firsts included the use of damping devices incorporated into the structural system and the development of a new partition called “Shaftwall” that eliminated masonry in the building’s core. In addition, a rooftop space frame (outrigger trusses) mobilized the tensile and compressive properties of all columns, controlling the deformation from unbalanced heating and cooling of long columns and provided the foundation or “root” for the TV mast.

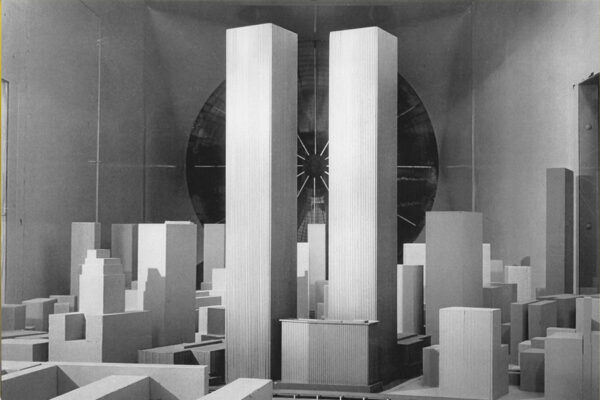

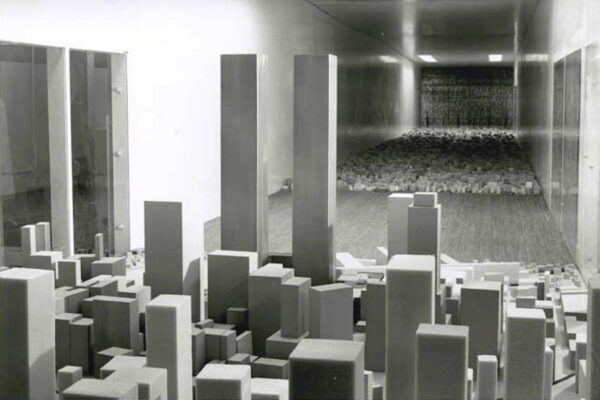

Wind Tunnel Testing

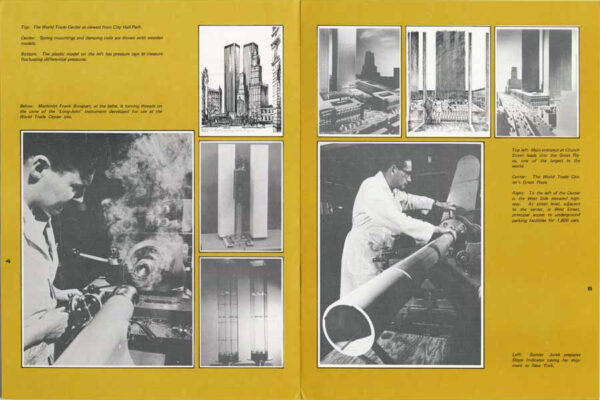

The World Trade Center was the first skyscraper design to be tested in a boundary layer wind tunnel, which replicates natural wind. Air flow around tall buildings creates turbulence and eddies that can cause vibration or sway. These effects can be accurately predicted by three kinds of tests. Special highly accurate models are built to represent the building’s form and nearby surroundings, often at a scale of 1:400.

A “pressure tap” model, as in the lower large photograph in this case, measures local pressures on the facade using hundreds of tiny tubes, or taps, connected to a computer.

A “force balance” model measures overturning of the entire building as wind gusts strike randomly.

An “aeroelastic” model, as in the upper large photograph in this case, also measures overturning, but includes the effect of the natural rate of rhythmic rocking back and forth, known as the building’s period.

From these studies, the engineers were able to analyze and predict the definition of both the steady-state and the fluctuating wind pressures on the facade; the steady-state and dynamic behavior of a tall building in turbulent wind; and a quantification of the increase in street-level winds associated with the construction of a high-rise building. They also developed a new theory of the prediction of the breakage rate of glass subjected to the natural winds of the atmosphere.

While now standard practice in the technology of high-rise design, the pioneering effort for the World Trade Center required significant reconstruction of laboratory facilities. Ultimately, three different wind tunnels at three different labs were used: one in the United States (Colorado State University), one in the United Kingdom (National Physical Laboratory, Teddington), and one in Canada (The University of Western Ontario).

Steel: Design, Contracts, and Prefabrication

Design

A key aspect of the innovative engineering of the World Trade Center was the detailed design of the new thin-shell or "tube" construction, which used many different strengths of steel to respond to the varying loads and external forces on the buildings' structure.

A family of steels—from plain carbon to quenched and tempered steels—were used to meet the required strength, both by the type of component, such as wall panels or floor trusses, and often by the location within the structure based on analysis and wind-tunnel testing. This approach resulted in both structural efficiency and significant savings in the purchasing of hundreds of tons of structural steel. The design allowed for column-free space of 60 feet clear span, with less steel and a lower story height than is found in most 50-story buildings.

Prefabrication

Another area of innovation included the prefabrication of structural components developed to a point never before achieved in high-rise buildings. There were nearly 6,000 prefabricated wall panels, generally three stories high and three columns in width, 36 x 10 feet, with the heaviest units weighing 22 tons. On the lower floors, some units measured 56 x 10 feet and weighed as much as 54 tons. There were also 5,716 prefabricated floor panels, generally 20 x 60 feet, including the steel deck and electrical raceways; this design allowed for the floor-to-ceiling height to be kept to 12 feet.

Digital Format

For the first time, the detailed design for most of the steel work was presented in digital form with IBM cards, rather than in conventional drawings. Using only data cards from the design as input, 55,000 tons of structural steel was detailed by computer and checked with the fabricators through the exchange of data cards.

Contracts

When the Port Authority rejected the bids for the overall project from the dominant steel companies US Steel and Bethlehem Steel, the engineers’ detailed specifications for the different steel components made it possible to divide the work into multiple contracts to be bid by smaller, more specialized companies. As John L. Tishman and Leslie E. Robertson explain in the audio clips here, ultimately there were eleven basic steel contracts and thirty-nine different fabricators.

Tishman Contributions

John Tishman, then the president of Tishman Realty and Construction, Inc., was the general contractor for the World Trade Center. In these audio excerpts from a 2002 lecture for The Skyscraper Museum, presented with Leslie E. Robertson, the chief structural engineer of the towers, and in a solo oral history recorded in August 2006, John Tishman describes four key features of the buildings’ design that were changed in response to his suggestions to facilitate construction and stay on budget:

- Moving the mechanical systems to the lower levels of the building, rather than following the conventional practice of placing them on the roof.

- Chamfering the corners of the buildings to create a 2-story opening to allow for hoisting materials into the interior.

- Dividing the steel contracts for bidding by specialized suppliers to keep down costs.

- Substituting high-polished aluminum cladding for the tower columns rather than stainless steel.

The Elevators

The Twin Towers were the first buildings in the world with an express elevator system. Much like the New York City subway, elevators made express stops at "sky lobbies" on the 44th and 78th floors. Passengers transferred to local elevators which brought them to their offices.

Double-decker elevators, which had been used in skyscrapers such as 70 Pine St., were not feasible because of the design's insistence on dramatic 74 foot tall lobbies.

The express elevators travelled at a speed of 27 feet per second (18.4 miles per hour). Each held a maximum of 55 people and had a weight capacity of 10,000 pounds. Engineers estimated approximately 450,000 "passenger movements" per day.

The TV Antenna

In 1967, the PANYNJ agreed to erect a television antenna on the roof of

the North Tower, because it was feared the structures would interfere with the stations’ signals transmitted from the Empire State Building.

Architect Minoru Yamasaki vehemently opposed the mast, arguing that it would destroy the symmetry of the towers and "throw the silhouette of

downtown Manhattan out of balance." His entreaties were not successful, but various disputes and lawsuits held up the project for ten years.

In 1977, a deal was reached between the PANYNJ and the Television Broadcasters All-Industry Committee to erect the antenna and to give the stations free rent until their leases with the Empire State Building expired in 1984.

In 1979, photographer Peter B. Kaplan documented the construction of the 360-foot mast atop the North Tower, spending twelve days aloft with the ironworkers installing the antenna. Broadcasts began in June, 1980.

Inside the Towers

The floor plans of the Twin Towers measured slightly more than 200 feet square, comprising an acre, minus the core area of elevator shafts, circulation, and mechanical systems. The “tube” construction with its exterior bearing wall and 40- to 60-foot long floor trusses provided column-free space in the offices. This “open plan” was a favored feature of postwar office buildings and contrasted dramatically with the typical space in earlier twentieth-century skyscrapers such as the Empire State, where a 3D grid of the steel skeleton structure placed columns every 18 to 22 feet.

The lower stories of the North Tower opened to tenants December 16, 1970, even before the construction topped out. Despite the public relations trumpeting, leasing by private companies for the more than 4 million square feet available in each building was slow. A major portion of each tower was filled by the government offices of New York State and by the operations of the Port Authority itself.

The distinctive characteristic of the towers’ interiors was the thick column and narrow window bay—18 inches of column and 22 inches of glass—that created the bold striped effect reproduced in our exhibition installation. As a consequence, views were limited, and the only real panoramas were experienced on the top floors of each tower where the columns narrowed and the window area increased. The restaurants of Windows on the World in the North Tower and the observation deck in the South Tower occupied these prime floors.

Critique and Response

Over the decade of the development and construction of the World Trade Center project, The New York Times architecture critic Ada Louise Huxtable wrote several pieces, from a first, mostly positive reaction to the design unveiled at the January 1964 press conference, to a brilliant, ambivalent essay in 1966, quoted in our introduction to the exhibition, that asked: "Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Bldgs?" In that piece she placed the ambitions of the project’s planners, architects, and engineers in the broader scope of the ideology in those professions and of inexorable forces of modernization and urban change:

The final, inescapable fact remains that architecture is now breaking scale, and style everywhere. (In his secret heart there is hardly an architect who doesn’t want to do so.) The objective historian realizes that the 20th century is in the transition to a remarkable new technology and a formidable new environment. . . Who’s afraid of the big, bad buildings? Everyone, because there are so many things about gigantism that we just don’t know. The gamble of triumph or tragedy at this scale—and ultimately it is a gamble—demands an extraordinary payoff.

Her appraisal in 1973 of the finished buildings, reproduced here, registered her colossal disappointment with the architecture, which she summarized in the afterward oft-quoted description "General Motors Gothic."

The review precipitated a seven-page letter of response from Minoru Yamasaki. The letter is a thoughtful, point-by-point defense of his architectural principles and of the Trade Center’s design, in many ways as clearly and eloquently stated as Huxtable’s own critique.

Thanks to Leslie E. Robertson for sharing this copy of the letter with the Museum.

A City in the Sky and a World Apart

The vast dimensions of the World Trade Center created a veritable vertical city. The rentable area in the complex, twelve million square feet, at the time of construction exceeded the total downtown office space of Philadelphia, Los Angeles, or Boston. The population of workers in the towers numbered around 47,000 in 2001, and about 100,000 commuters passed daily through the subway and PATH stations. Many shopped in the concourse beneath the plaza, making it, per square foot, the highest-grossing mall in the country.

But in many ways, the sixteen-acre site stood a world apart from the rest of the city. The superblock was divorced from the street life of lower Manhattan, and the monumental towers rising from a generally vacant plaza established a zone of inactivity at the heart of the complex. Most New Yorkers had no occasion to step inside the Trade Center unless they worked there or shuttled to the top-floor restaurants of Windows on the World or the observation deck by express elevators.

This section of the exhibition recalls the life of the towers through video and audio clips that animate the architecture and collect the comments of key figures responsible for its design and operation; others simply record memories of the buildings. The room also attempts to evoke the experience and scale of the structures through light columns that reproduce the 18-inch steel box columns and the 22-inch window bay that marked the distinctive dimensions of the Twin Towers.

The dramatic installation design by Local Projects features light columns that use the gallery’s unique floor and ceiling of mirror-polish stainless steel to create the illusion of the slender pin-stripe columns of the towers’ facades